BBC News, Cambridgeshire

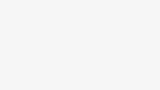

Tamar Makin/Hunter Schone

Tamar Makin/Hunter SchoneResearchers behind a new study into phantom limb pain believe it could change how the phenomenon is treated.

The universities of Cambridge and Pittsburgh followed three people due to have one of their hands amputated.

Phantom limb pain is experienced as a sensation or itch seemingly coming from the limb that is no longer there.

The academics’ work found the brain’s internal map of the body, in the somatosensory cortex, remained unchanged even after amputation.

They revisited the participants three months, six months, and up to five years after amputation and found their brains still lit up in the same areas that controlled the now absent limbs.

Senior author Prof Tamar Makin, from the University of Cambridge, said previous studies may have misinterpreted what was happening.

“Because of our previous work, we suspected that the brain maps would be largely unchanged, but the extent to which the map of the missing limb remained intact was jaw-dropping,” she said.

“Bearing in mind that the somatosensory cortex is responsible for interpreting what’s going on within the body, it seems astonishing that it doesn’t seem to know that the hand is no longer there.”

As well as the possibility of better treatments, researchers said it suggested building robotic limbs to connect to the brain could be more straightforward than previously thought.

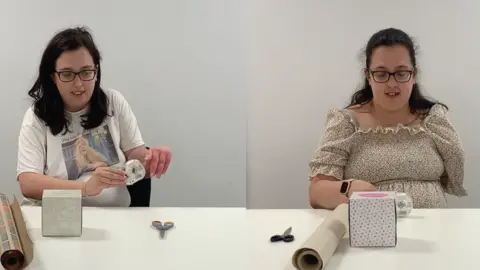

Tamar Makin/Hunter Schone

Tamar Makin/Hunter SchoneIt was a commonly accepted view among neuroscientists that the brain rewired itself after an amputation.

Current treatment approaches focus on trying to restore representation of the limb in the brain’s map, but randomised controlled trials to test this approach have shown limited success.

Co-author Dr Hunter Schone, from the University of Pittsburgh, said the most promising therapies involved rethinking the amputation surgery, like grafting the nerves into a new muscle or skin, so they have a new home.

“This study is a powerful reminder that even after limb loss, the brain holds on to the body, waiting for us to reconnect,” said Dr Schone.

Research is also under way into how movement and sensation could be restored to paralysed limbs or if amputated limbs might be controlled by a brain interface.

“Our findings provide a real opportunity to develop these technologies now,” said Dr Chris Baker, from the National Institute of Mental Health.