“Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links.”

Here’s what you’ll learn when you read this story:

-

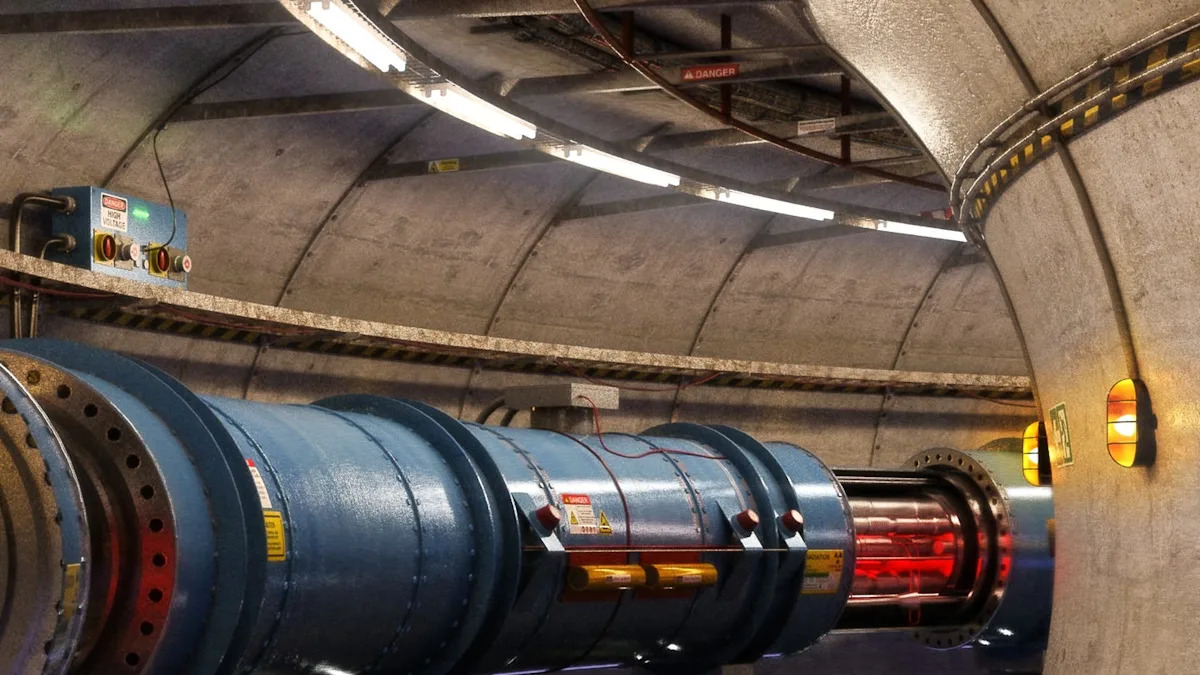

CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron will turn 50 in 2026—and it has a resonant “ghost.”

-

Using…

“Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links.”

Here’s what you’ll learn when you read this story:

CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron will turn 50 in 2026—and it has a resonant “ghost.”

Using…