In his search for nonopioid treatments for pain and for ways to separate opioids’ pain-relieving properties from their addictive ones, UNC-Chapel Hill’s Grégory Scherrer is using innovative approaches:

Scherrer is an associate professor of cell biology and physiology at the UNC School of Medicine, the UNC Neuroscience Center and the school’s pharmacology department.

Opioids are essential for treating cancer and surgical pain but can cause dependence. But finding pain drugs has had a high failure rate in the past 20 years, according to Scherrer. “Less than 1% of drugs that enter clinical trials are approved and have sufficient efficacy. We need new ways to discover and evaluate pain drug candidates,” he said.

Modeling the nervous system

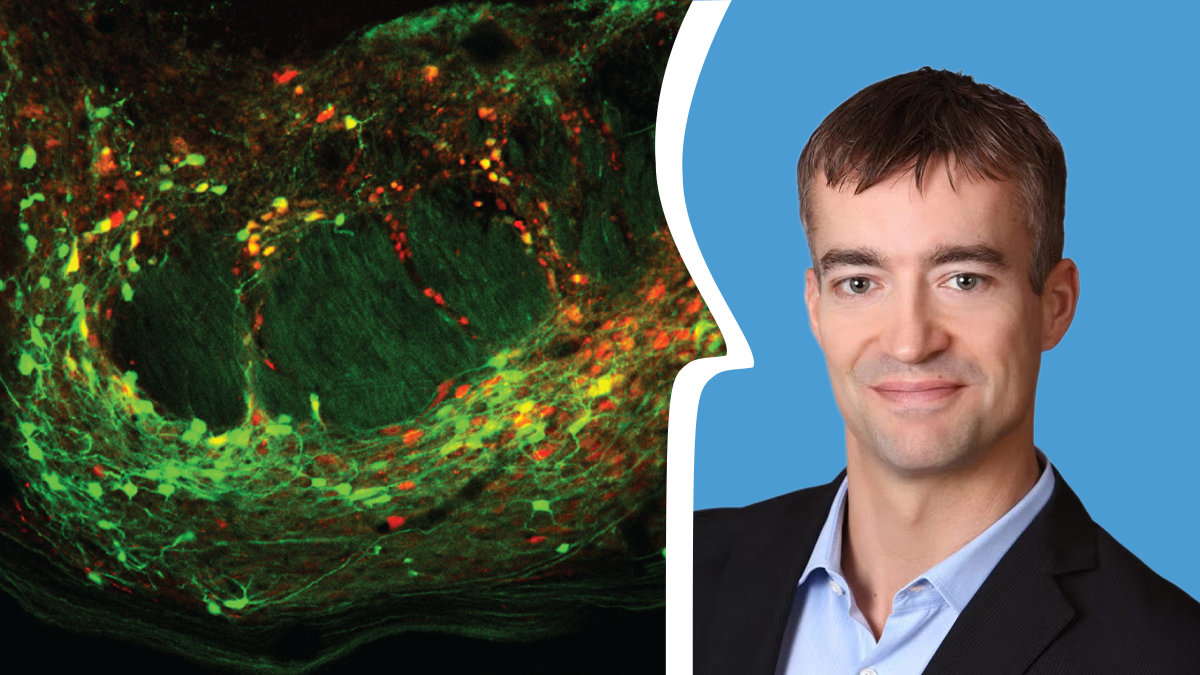

One lab project involves building tiny 3D tissue cultures to model how pain travels to the brain. Researchers reprogram human skin cells into stem cells, then guide them to become pain-sensing nerve cells. They grow those cells into tiny tissue cultures and connect them into a circuit.

“They’re small balls in a Petri dish that model distinct parts of the nervous system and that we can connect,” Scherrer said. The bundles mimic sensory nerves like those in a hand or foot; a spinal cord; the thalamus, which is like a relay station; and the brain’s cerebral cortex, which produces pain perception.

When the circuit is complete, the lab team can add a new drug and a pain-causing substance to determine if and where the drug affects the pain receptors. They watch how signals move between the cells using special dyes and electrical recordings.

The system helps researchers understand chronic pain, test drugs and study conditions like nerve damage without using humans or animals.

Turning off neurons to stop pain

The lab also examines how nerve cells, or neurons, in the amygdala — a brain region that generates emotions like fear and discomfort — make pain hurt. Opioids mostly act on that emotional aspect.

“We can artificially turn off such cells in mice so they behave like humans who don’t feel the unpleasantness of pain because the brain regions that contain those cells have been damaged,” Scherrer said. “If we can do that, we can develop safer treatments that reduce chronic pain’s emotional toll without opioid side effects.”

In an overdose, opioids shut down breathing. Scherrer is trying to develop new drugs that act only on those nerve cells delivering pain emotions.

Turning off these neurons doesn’t remove sensation. “You still know something’s not quite right, but it’s not as unpleasant,” he said. RNA sequencing helps identify genes in pain-recognizing neurons for precision treatments to selectively silence those driving chronic pain.

Treating pain with placebos

The lab also studies placebos — substances with no therapeutic effect that are used as controls in drug testing.

“Many possible pain drugs have failed because they didn’t prove effective enough to beat a placebo’s perceived pain reduction,” Scherrer said. “When people with chronic pain enter a clinical trial and are excited about possible relief, they can have a strong placebo response.”

The lab’s 2024 Nature study showed that expecting pain relief can trigger the brain to produce opioids to ease pain. Scherrer said such findings indicate a need to think differently about drug review and testing.

Scherrer’s team is exploring ways to design trials that minimize placebo response or pair placebos with a drug’s mechanism. “For some people with a strong placebo response, their pain can drop from an eight to a three without any active ingredient,” he said.