Study characteristics

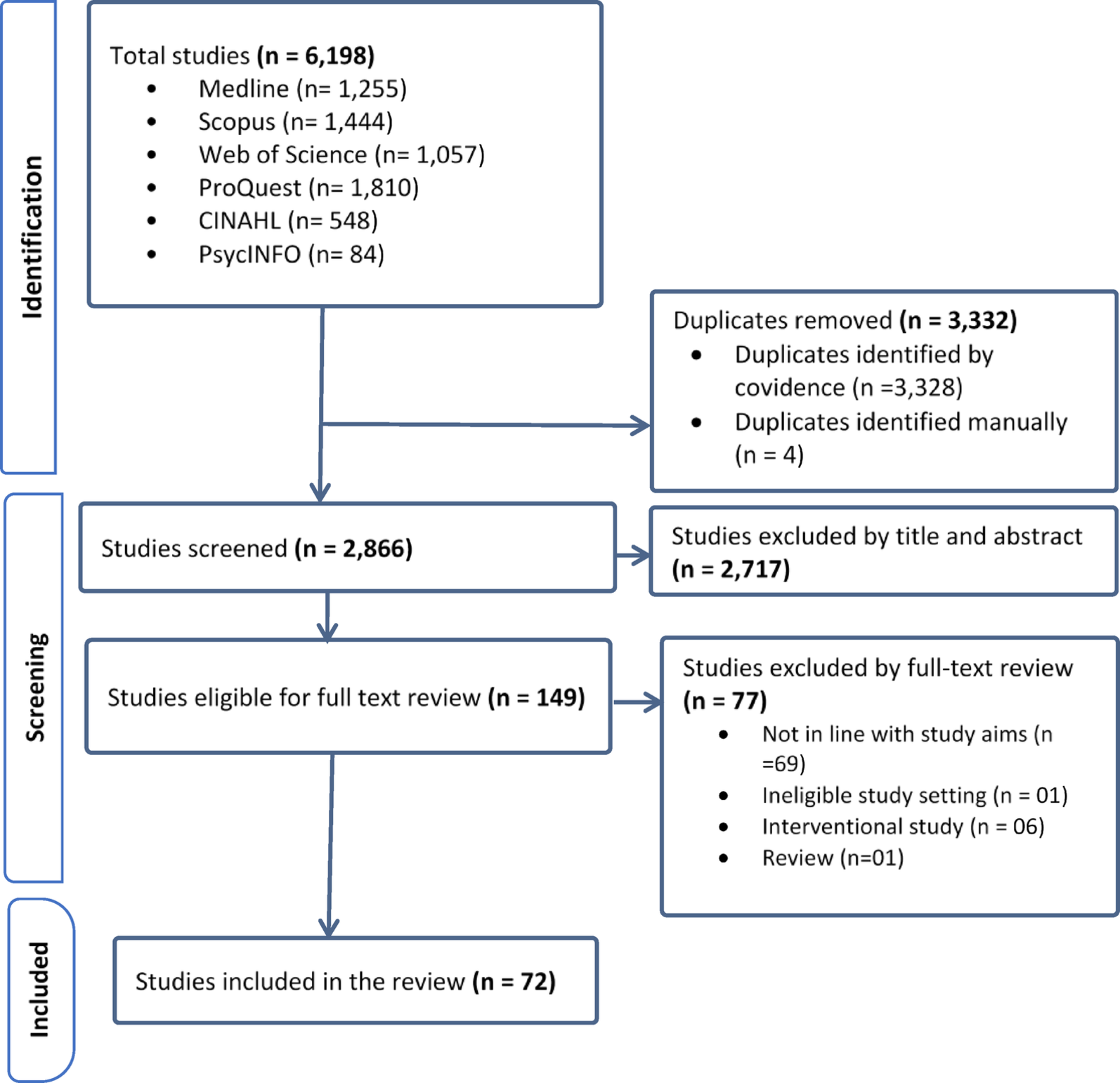

The searches identified 6,198 articles from databases. After screening and full-text review (Fig. 1), 72 articles met our inclusion criteria. These included 23 quantitative, 15 mixed-methods, and 34 qualitative articles. Three studies (two quantitative, one mixed-methods evaluation) reported on the overall HSR and each of its specific framework components. Additionally, one qualitative study conducted in the pastoral community of Ethiopia used the HSR framework domains to report its findings. Most included articles were from Ethiopia (n = 51, 70.8%), with seven from Tanzania, nine from Kenya, and the remaining five from other East African countries. The study populations in the included studies were diverse, including women, men, religious leaders, Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs), Health Development Armies (HDAs), religious leaders, local leaders, healthcare providers (nurses, midwives, doctors, etc.), Health Extension Workers (HEWs), maternal health coordinators, healthcare managers, and policy experts (Supplementary Table 3).

Overall health system responsiveness

The challenges, successes, and strategies of HSR and each of its domains toward universal maternity healthcare services were reported in Supplementary Table 4. The overall responsiveness of health systems to obstetric care ranged from 45.8 to 75.6% [17, 24, 25]. Several factors have been linked to responsive maternity care, including maternal age, residence in urban areas, obstetric complications, birthing by caesarean section, referral during labour, the duration of labour, and maternal satisfaction during maternity care [17, 24] (Supplementary Table 4). The articles included in the overall HSR and across its domains were indicated in Table 3.

This review illustrated that respectful, non-discriminatory, and rights-based care, along with welcoming behaviours by staff, enhanced responsiveness and support the achievement of universal maternity care. Conversely, where there is a loss of women’s autonomy, exclusion from decision-making, and lack of informed consent, this weakened health system responsiveness and hindered access to universal maternity care. Disrespectful practices by healthcare providers during maternity care, including abuse, discrimination, and denial of companion support, reduced service quality and discouraged women from utilizing maternity care. High client load, poor hygiene, workforce shortages, and lack of provider choice at health facilities further compromised responsiveness and access to universal maternity care. Communication challenges, including language barriers and use of medical jargon words, weaken provider-client relationships. Delays in care and long waiting times also resulted in poor responsiveness of maternity care services. We also described the magnitudes, strengths, and areas of improvement across each domain of HSR for maternal healthcare services in Table 4.

Autonomy

Seventeen articles described self-directing freedom and women’s informed choice about their maternity care. The proportion of women exercising autonomy in child birthing service ranged from 57.9 to 66.8% [17, 24, 25], indicating a moderate level of participation in decision-making. Qualitative findings suggested although healthcare providers were expected to adhere the standards, healthcare providers conducted procedures without obtaining informed consent and providing adequate explanation of the procedure [26,27,28,29]. The loss of women’s autonomy in maternity care, which undermined their decision-making power and right to refuse unfavourable conditions [28], reflected poor health system responsiveness. Evidence from Ethiopia and Kenya shows limited decision-making power and lack of informed consent from women for their caesarean sections, contributing to mistrust in public healthcare services [29, 30]. A woman who delivered at a private facility mentioned that:

“…Like for me, when I had my first pregnancy, there was a lady who told me since it was my first pregnancy, I should not go to [Major Maternity A] because if I go there they will just take me to the theatre and operate on me and so I was very afraid…” (FGD, Mother of two who delivered at a private facility B, performing a procedure without obtaining consent affected service utilisation, Oluoch-Aridi et al.) [29].

Excluding women from decisions regarding childbirth options, companionship during labour, and medical procedures [10, 31, 32] posed a significant challenge to maternity healthcare services. However, obtaining the consent of women before doing any procedures and examination [33,34,35] maintains women’s autonomy. Explaining the procedure and obtaining consent creates an interpersonal connection, establishes rapport, and avoids blame or legal actions [34]. Respecting women’s right to information, informed consent, choices, and refusal [36] helps to maintain women’s autonomy during maternity care. Involving women or their families in decision-making and sharing information regarding their health services empowers them to improve continuity of care, adherence, and referrals [34, 37, 38]. An urban in-depth interview (IDI) participant reported that:

“No women must undergo any procedure without her informed consent. Women have the right to know and willingly consent to or refuse a procedure. The procedure might be important, but her consent is necessary.” (Urban IDI, performing a procedure without obtaining consent is not acceptable, Adinew et al.) [33].

Obtaining informed consent from women prior to examinations and procedures were essential for upholding their autonomy throughout maternity care [30, 32, 34, 37]. Ensuring the provision of clear and comprehensive information, including the use of consent forms translated into the local languages of service consumers, further facilitated women’s active participation in decision-making regarding their care [30, 37].

Confidentiality

Twenty-six articles described the ability to maintain confidentiality of a woman’s health information during maternity care. Confidentiality in maternity care ranged widely, with maintained confidentiality reported between15% and 89.3% [17, 24, 25, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45] and other studies reported confidentiality breaching in maternity care between 35% and 66.2% [46,47,48,49,50,51]. Midwives assured they never share women’s information with non-concerned individuals [52]; for example, a 32 years old experienced midwife mentioned that:

“(…) the information they provide is kept confidential, the information women provide to us remains with us and women will not hear them on the street or elsewhere (…).” (IDI, a 32 years old midwife with 7 years of experience, breaching of confidentiality could be the concern of women, Heri et al.) [52].

Qualitative studies also suggested ensuring the privacy of information was a challenge during maternal healthcare service [27, 36, 43, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59] due to the nature of the care. Sharing a single room by two or more women due to a shortage of spaces within maternity wards was an obstacle to care providers’ ability to provide confidential information to the women [36, 53, 56, 58, 59]. Lack of screens and absence of partitions between delivery couches were also a barrier to maintaining the confidentiality of a woman because of the open and narrow nature of the labour wards or child birthing rooms [54, 55]. An IDI study participant reported that:

“There are many challenges. Let us talk about infrastructure and hospital capacity. When we receive many clients two women share the same bed which interferes with the privacy of the client, at that time the only thing to do as healthcare provider is to maximize the benefit from each one.” (IDI, Participant 18, poor privacy due to lack of adequate space in maternity wards breaches confidentiality, Uwamahoro et al.) [36].

Continuing to uphold women’s privacy during their maternity care was important to maintain the confidentiality of women’s healthcare information [43, 52, 53]. Building or renovating additional rooms for maternity care allowed one woman admitted per room to improve privacy and confidentiality [53]. Modifying service rooms in a way that can maintain client’s confidentiality and privacy were identified as an effective measure [43].

Dignity

Forty-one articles described dignified care during maternity care. The proportion of women receiving dignified care ranged from 70.8–80% [17, 24, 25, 39, 44, 53], while other papers reported non-dignified maternity care was reported from 25.5–60.4% [46,47,48,49,50, 60]. The qualitative findings also implied beating, slapping, pinching, physical assault, and forcefully opening women’s legs were common physical abuses practised during childbirth [27, 28, 36, 61,62,63,64]. A participant proudly explained that:

“Myself and a few of my colleagues at our workplace are nicknamed commandos because when we are on shift, we never end up with birth asphyxia. We are very tough with women during labour. If women fail to collaborate, they could be slapped, pressure applied to rescue her life and that of a child” (IDI, physical abuse affected dignity, Mwasha et al.) [27].

Physical abuse during maternity care hurt and compromised the ability of care providers’ to act in a moral way [65]. Lack of privacy during child birth and physical assessments caused humiliation, anxiety, pain, and discomfort [10, 28, 32, 57, 59, 63, 66,67,68,69]; for example, a 39-year-old woman accompanied her neighbour to health facility stated that:

“.when my neighbour gave birth in the facility, the midwife invaded her privacy and conducted too many vaginal examinations, which was dehumanizing and shameful. So, how am I able to use the treatment room knowing that my friend had a tough experience there? I preferred to give birth at home with the assistance of a TBA, as she can give me more privacy and control over the situation than the midwife at the health facility” (IDI, Para 6, 39-year-old woman, frequent invasion of women’s body affected privacy and dignity, Zepro et al.) [10].

In addition, a 32-years-old mother described her experience, as follows:

“. there were no curtains to cover my body, the window was broken so that everyone can see you from outside or inside of the delivery room.generally, I wasn’t that much satisfied with their care” (IDI, a 32-year-old mother, absence of infrastructure like curtains affected privacy and dignity of woman, Dagnaw et al.) [32].

Verbal abuse, including shouting, insults, yells, verbal harassment, use of unpleasant language, and lack of compassion undermined responsive maternity care by degrading women and violating their dignity [10, 26,27,28, 31, 32, 36, 39, 52, 59, 61,62,63,64,65,66, 69,70,71,72]. Healthcare providers often belittled and verbally abused women during labour, criticizing their performance and making derogatory remarks about their pregnancy choices, disabilities, and future childbirth capabilities [10, 59]. Some articles, however, reported slapping, pinching, or holding a woman forcefully on a delivery bed [33, 59, 70] and verbal threats [33] were believed to be acceptable to avoid adverse birth outcomes.

Healthcare providers occasionally denied providing maternal healthcare services and might not uphold the rights to be treated ethically and healthcare access of childbearing mothers [25, 72]. Experiencing unfriendly maternity care during childbirth was also a detriment to service utilisation [31, 68, 73]. Unfair healthcare service provision and stereotyping practices were other challenges that discouraged women from maternity care [10, 27, 59, 71]. Lack of sympathy, lack of hospitality, poor receptiveness, neglect, and negative attitudes of healthcare providers contributed to the unpleasant experiences of the women [10, 28, 64, 74, 75].

“While I delivered my second baby at a health centre I was in pain and shouting for help to the midwife who was chatting with her friends. She didn’t show any concern to me and one physician also came and yelled at me. I suggest that these people have to in the first place respect their clients and also know their professional duties and responsibilities” (IDI, Participant 06, verbal abuse and negligence affected dignity, Sendo et al.) [64].

In contrast, the initiation of non-discriminatory care [35, 76] and respecting the right to equality and equitable care, the right to liberty, and freedom from coercion [36] improved dignified maternity care. Some healthcare providers believed and practised abuse-free care during maternity care [33, 69]. Additionally, healthcare providers emphasised maintaining privacy and dignity by using screens and curtains, while also acknowledging that shouting at women during maternity care is unacceptable [37, 61, 70]. A woman in a rural IDI described that:

“It is never acceptable to forcefully open a woman’s legs even if it is to save her baby. The only thing the provider can do is to tell her the importance of opening her leg. If she does not comply, it is better to involve her family to convince her than forcefully opening her leg. It is against her rights.” (Rural IDI, physical abuse affected dignity, Adinew et al.) [33].

Providing training to healthcare workers, along with conducting supportive supervision and mentorship, was critical for addressing the challenges associated with ensuring dignified care during maternity services [53, 70]. Fostering a care environment that is free from abuse, discrimination, and hostility were essential for enhancing health facility childbirth rates [76]. Furthermore, the recruitment of additional healthcare workers was a key strategy to mitigate the impact of excessive workloads, which can contribute to the provision of non-dignified care [47].

Basic amenities

Nineteen studies explained the physical infrastructure and conducive care environment aspects of healthcare during maternal healthcare services. Overall, the quality of basic amenities during childbirth service ranged from 45.8 to 65.8% [17, 24, 25]. Qualitative findings identified the lack of basic amenities, including poor hygiene of delivery beds and rooms, dirty washrooms, unhygienic health facilities, and improper practices by healthcare workers and support staff were the critical barriers for maternity care [10, 28, 62, 63, 67, 71, 77]. A 25-years-old parity 1 woman replied that:

“When I was admitted to the hospital, the beds were not cleaned well. A health care provider said to me, “Lie down on that bed”. I could not refuse because I thought the provider might get upset with my suggestion, and my subsequent care might be affected” (IDI, 25 years old woman, parity 1, lack of cleanness affected amenities, Werdofa et al.) [28].

A parity 3 woman who participated in a focus group discussion (FGD) also reported that:

“At the time of labour, there were blood drops on the delivery bed, the surface and bed linen smelled bad. There was no water in the facility. For example, I was bleeding; my mother took me to the bathroom, but could not wash me. This year I did not see this. I think there are changes, maybe” (FGD 2, Parity 3, lack of water in the bathroom affected amenities, Zepro et al.) [10].

Another study participant mentioned that:

“The toilet and shower rooms were filthy and smelled terrible. There was no running water or electricity in the delivery ward. Since the facilities are far from my home, it was a problem to have proper food and drink. My family was challenged with taking care of my food” (IDI, parity 3, absence of running water or electricity in labour ward affected amenities, Zepro et al.) [10].

Poor physical amenities, including inadequate infection prevention protocols, poor room arrangements, and unfavourable working environments, were critical challenges during maternity care [29, 68, 75]. The lack of essential hygiene supplies, such as, water, feminine hygiene products, cotton wool, sanitary pads, sheets, detergents, and reliable electricity with backup generators, hindered the establishment of a clean and comfortable working environment in the maternity wards [10, 25, 28, 54, 62, 77, 78]. In addition, shortages of health facility supplies and equipment, such as lack of enough beds and bed sheets, blankets, shower rooms, personal protective equipment, delivery couches, bedpan, and waiting rooms, were the identified detriments for maternity care [32, 39, 71, 75, 78]. Additionally, the absence of a maternity-specific operating theatre for caesarean sections affected the provision of reliable maternity care [58]. Inadequacy of food and poor food quality were also among the barriers that affect the quality of basic amenities in a healthcare facility [63, 77].

Care providers and service consumers acknowledged using sterile equipment and clean bed linen in the facilities to keep the quality of basic amenities [29, 37, 67]. Healthcare facilities should keep their compound clean and give sufficient food for women [29, 62] to enhance the quality of basic amenities. Fulfilling essential equipment and supplies helped to provide comfortable and hygienic care [24, 28, 39] regarding the quality of amenities.

Choice of care provider

Twenty-one papers described women’s ability to choose their care providers during maternity care. The proportion of women who chose their care provider during obstetric care ranged from 41.6 to 68% [17, 24, 25]. The qualitative studies also indicated women might not have the opportunity to choose healthcare providers during their maternity care [10, 25, 38, 56, 66, 78, 79]. Concerns about male healthcare workers, along with provider incompetence, inexperience, and poor attitudes, led some women to avoid childbirth at health facilities [10, 56, 66, 72, 79]. A parity 3 IDI participant replied that:

“.Women in my locality frequently explain that anger, sadness, and shame accompany a loss of culture and being distant from Allah’s (God) laws about being seen naked by strangers (male midwife) in the health facility. Male birth attendants are also involved in assisting women in labour. That is quite against our faith and culture. God prohibits us from doing so. I fear this will cause punishment from God; Almighty Lord” (IDI, parity 3, male care provider was not the choice of woman for their maternity care, Zepro et al.) [10].

Women’s limited access to diverse providers hinders quality of care by restricting access to varied expertise and skills [38]. Frequent provider changes during ANC visits caused dissatisfaction and interruptions, as some women preferred consistent care and disliked repeating their health history [75]. For example, a participant of an IDI said that:

“Having different service providers to attend a single pregnant woman at her ANC visits is one of the potential reasons for dissatisfaction and interruption as pregnant women are not comfortable to tell their entire health history to different people and this is evident as many of them ask for the person who provided the service initially and will leave if s/he is not around” (IDI, frequent change of care provider was not favourable for the women during their ANC visits, Tsegaye et al.) [75].

Insufficient health care providers and workforce turnover posed various challenges, such as disruptions in service operations, loss of experienced and trained staff, increased staff fatigue and workloads, negligent care, resulting in low quality and discontinuation of services [28, 31, 62, 64, 68, 75, 78]. Poor health workers’ discipline and readiness were the other barriers to maternal healthcare delivery [68, 71]. Weak relationships between providers and women might also fuel legal disputes between MCH clients, care providers, and healthcare facilities [65]. A client at a health center stated:

“Bad relationship negatively impacts maternal and child health services…There is a particular nurse; if I go to the regional hospital and find her, I avoid receiving care from her altogether. I [am] better [to] go back home without treatment or to a traditional healer…” (FGD, Client at Health center, care providers who had poor acceptance by service consumer affected maternity care and responsiveness, Isangula et al.) [65].

Challenges in recruiting specialists and healthcare workers, along with limited supervision by senior professionals, negatively affected the quality of maternity care [28, 63, 68]. Frequent unsupervised examinations by students also contributed to women’s experiences of disrespectful and abusive care [69].

Respecting women’s preferences for healthcare providers, coupled with increased investment and recruitment of adequate number and variety of care providers, including the hiring of female healthcare professionals, has the potential to enhance responsiveness for maternity care [24, 36, 56, 75].

Communication

Thirty-three studies revealed the exchange of information and instructions between healthcare workers and women during their maternity healthcare services. The proportion of women who had effective communication with care providers during their care ranged from 46 to 76.3% [17, 24, 25, 43, 53, 73, 80]. Qualitative studies identified the impact of communication gaps or inadequate information on maternity care service utilisation [25,26,27, 29, 31, 52, 53, 63, 67, 81]. Poor care provider-client relationships, use of medical jargon or non-local languages, and hierarchical one-way communication practices hindered maternity care provision and discouraged women from engaging with health services [10, 26, 31, 62, 65]. For example, a 35-years-old key informant interview (KII) mother reported that:

“Sometimes, there is a communication gap before, during and after giving services. Most of the time, [staff] try to give service or do procedures without communicating the mother well and left the room.” (KII, a 35 years old mother, communication gaps were among the common challenges during maternity care, Girma et al.) [25].

Another participant reported that:

“I didn’t go to school; I don’t know English, but if they (providers) speak, I notice the actions and understand…. they did not talk to me directly, and I didn’t understand their conversations except their actions, which showed me that these guys must be talking about me on something…” (IDI, Facility 2, language is one of the communication barrier during maternity care, Metta et al.) [26].

Inadequate referral linkages, poor inter-level communication, limited decision-making power among midwives regarding referrals, were critical barriers to maternity care service utilisation [78, 82]. Additionally, misinformation, poor provider-woman interaction, fear of disclosing bad news related to COVID-19, and providers’ rude or abusive language contributed to the negative perception of healthcare providers and a decline in trust towards healthcare facilities [56, 58, 65, 74, 83]. The flow of information during pandemics like COVID-19 frustrated maternity care consumers and impacted their use of services [83]. A woman who gave birth at home mentioned that:

“I gave birth when the issue of Corona was hot in our country. My family and I felt sad as we heard the frightening news on the radio. Then my husband and I decided not to go anywhere… death is inevitable…” (FGD, home childbirth, poor communication means during pandemics affected responsiveness of maternity care, Abdi et al.) [83].

In contrast, effective communication marked by respectful greetings, provider introductions, honest dialogue, use of clients’ names, attentive listening, and positive non-verbal body gestures enhanced provider–client rapport and significantly facilitated maternity care utilisation [32, 34, 35, 37, 61, 62, 67]. Positive experiences, including security guards or care providers welcoming women at facility entrances, highlighted the responsiveness of the health facility [62]. In addition, women appreciated when healthcare providers gave women their phone numbers to ensure continuous communication, allowing women to ask questions and interact freely, which is crucial for understanding and addressing their needs [52, 71]. Trust between care providers and women improves care-seeking behaviours, emotional well-being, treatment adherence, and facility reputation while encouraging openness and increasing the likelihood of return visits for maternity care [65, 84, 85]. Making women feel well before care, ensuring continuity with the same provider, and addressing them by name helped build trust between care providers and women [32, 34, 38, 65]. For example, maternity care service consumers expressed their satisfaction when health care providers called by name and explained the procedures they perform; however, they noted that not all providers consistently demonstrated this practice [32]. This is illustrated by the following statement from a 29-years-old mother, who said:

“.I was very satisfied if the health care providers called me by my name and if he [health care provider] explained what he is going to give me but. umm some of them didn’t do that.” (IDI, a 29 years old mother, effective communication increased women’s satisfaction and decreased their anxiety, Dagnaw et al.) [32].

Training and mentoring healthcare workers, along with conducting supportive supervision, are essential to improving communication and emotional support during childbirth, while fostering intersectoral collaboration to address misconceptions during health crises [53, 83]. Ensuring that procedures and medication purposes are clearly explained to women and encouraging them to ask questions promotes informed participation in their care [32]. Self-introduction of healthcare workers, applying two-way communication, employing technology for information sharing, and using polite language are vital for enhancing effective communication during maternity care [24, 29, 34, 52].

Prompt attention

Thirty studies examined maternity care provision within reasonable periods, even during non-emergency healthcare services, with reasonable waiting time and traveling time to healthcare. Between 62.1% and 96.3% of women received timely care during maternity services [17, 24, 25, 42, 45, 76, 86,87,88,89]. Qualitative studies indicated far geographical distance from healthcare facilities affected women’s timely maternity care [66, 71, 77, 90]. Long wait times and delays in receiving care upon arrival discouraged women from attending health facilities for maternity services [10, 29, 36, 39, 43, 56, 62, 63, 66, 68, 71, 73, 75, 90, 91]. Lack of staff and high workloads contributed to unequal and delayed provision of maternity care [29, 36, 39, 90]. A 34-year-old mother reported that:

“.The MNHC providers didn’t assess and evaluate me on time. But after my birth companion called his friend Dr. X. who was working in this hospital, they immediately started to assess and evaluate me properly as indicated. I think in this hospital, no one can get appropriate and timely care unless you have friends/relatives from MNHC providers. Generally, the service was biased.” (FGD, 34 years old mother, delay in care affected maternity care responsiveness, Amsalu et al.) [39].

Closure of healthcare facilities during the night, unreasonable delays, providers’ absenteeism or late entrance from work, and lack of equipment and supplies were other barriers to timely care of maternal health services [56, 66, 75]. A woman stated that:

“Health facilities in this district don’t work 24 hours. They do not have light in the night even. They close during the evening time and open morning when the people wake up.” (FGD-07, breastfeeding mother, Deynile, working hours of health facilities affected timely access to maternity care, Mohamed et al.) [56].

Timely maternity care in rural areas was hindered by poor road access, difficult topography, limited transport options, ambulance shortages, and transportation restrictions during pandemics [56, 64, 66, 71, 73, 83, 90],, all impacting responsiveness and access to universal maternity care. A woman at term pregnancy during the first phase of COVID-19 stated that:

“… during the first phase of COVID-19, I was a term [pregnancy], and my labor started very soon. I stayed about 4 hours at the bus station because there was no bus to go to a hospital, which is located 45 km away. My husband and I decided to go back home and seek help from a traditional birth attendant… ’’ (FGD, home childbirth, lack of transportation affected timely maternity care, Abdi et al.) [83].

The following quote from a 37-year-old Health Extension Worker (HEW) further illustrated these difficulties:

“. Also, there is a topographical difficulty and distance from a health facility. It is very difficult even for us [normal people or non-pregnant women], not only for a pregnant woman. It is difficult even to use traditional ambulance because of its [slope] and hill.” (FGD, a 37 years old HEW, topographical difficulty affected timely maternity care, Higi et al.) [71].

Instead, timely assessments and the consistent availability and preparedness of healthcare workers reduced delays, manage obstetric emergencies and improve efficiency and outcomes of maternity care for both mothers and babies [37, 62, 69]. Enhancing ambulance access, constructing maternity waiting rooms, improving road infrastructure, ensuring 24-hour availability of health facilities, providing timely and free maternity care, and fostering intersectoral collaboration contributed to facilitating timely maternity care [29, 43, 56, 62, 73, 76, 83]. Strengthening the collaboration with transport sectors was particularly crucial for addressing transport-related challenges during epidemics or pandemics, such as the COVID-19 transport restrictions, to ensure uninterrupted maternity care services [83].

Social support

Twenty-one articles reported on women’s social support or companion visits during maternity care. This includes regular visits by relatives and friends, practicing their cultures (e.g., religious practices) that do not impede healthcare activities, and receiving food and other consumables from relatives and friends. The proportion of women receiving social support or companionship during childbirth ranged from 13.8 to 69% [17, 24, 25, 55, 76, 86, 92]. The qualitative findings also indicated that, when women frequently were not allowed to have a companion during their maternity care, this made their experience at health facilities unfavourable [10, 26, 28, 37, 53, 55, 81, 83]. Healthcare providers often restricted companion access due to fear of witnesses during incidents and unsupportive administration, with the COVID-19 pandemic further limiting family support during facility-based childbirth [55, 81]. A 24-years-old primigravida woman stated:

“…. In some cases, hospitals restrict access to support people, which worry me a lot about who will be my helper during the childbirth process. I’m not sure what will happen; maybe I’ll get COVID-19 and won’t be able to nurse my child.…Who is going to stick by me?” (IDI, P-7, a 24 years old primigravida woman, restriction of companionship worried maternity care consumers, Cherinet et al.) [81].

Cultural preferences incompatible with health facility practices also deterred accessing maternity care [64, 66]. Specifically, the absence of celebration after childbirth at health facilities, in contrast to home births where family and community celebrate with traditional songs and provide care to the mother, such as feeding the mother porridge [64], highlighted a lack of cultural and emotional support in facility-based maternity care. The following quote illustrates the importance of these cultural celebrations:

“Following childbirth, neighbouring women will make some porridge and will serve the woman. They (women) will celebrate this special occasion by singing traditional songs and eating porridge. If childbirth takes place in the facility, you miss this wonderful event and the warmness of your home. I think this ceremony is unique to Ethiopian women” (IDI, Participant 01, absence of birth celebration at health facility affected maternal satisfaction during maternity care, Sendo et al.) [64].

In contrast, some healthcare providers did believe every childbearing woman has the right to have a birthing companion during maternity care service utilisation [33]. In addition, some facilities involving companions had various positive contributions, such as enhancing confidence in difficult situations, providing emotional support, facilitating referrals and continuity of care, persuading uncooperative women for necessary procedures like episiotomy, and linking the midwife’s instructions with the woman’s adherence during maternity care [28, 34, 35, 55, 93]. Birth companions might also identify complications, inform medical staff, and brought essential supplies [28]. As an example, a 25-years-old woman said:

“After I gave birth, one of my relatives hid from the health care provider and entered my partition. She yelled and notified the health care provider of the blood that had accumulated between my two legs. As medical personnel arrived at my partition, they checked my bleeding and provided the necessary treatment to stop it. So, if my relative had not come to my aid, no one would have noticed my bleeding, and I might have died because of it. For a mother, having a companion after childbirth is crucial” (IDI, a 25 years old, para 1, birth companion could have the ability to identify complications and informed to care providers, Werdofa et al.) [28].

Providing social support through continuous companionship during labour improved the quality of care [24, 92]. Improving infrastructure with better space and privacy at healthcare facilities reduced overcrowding and allow women to get support from their companions [37, 72, 81].