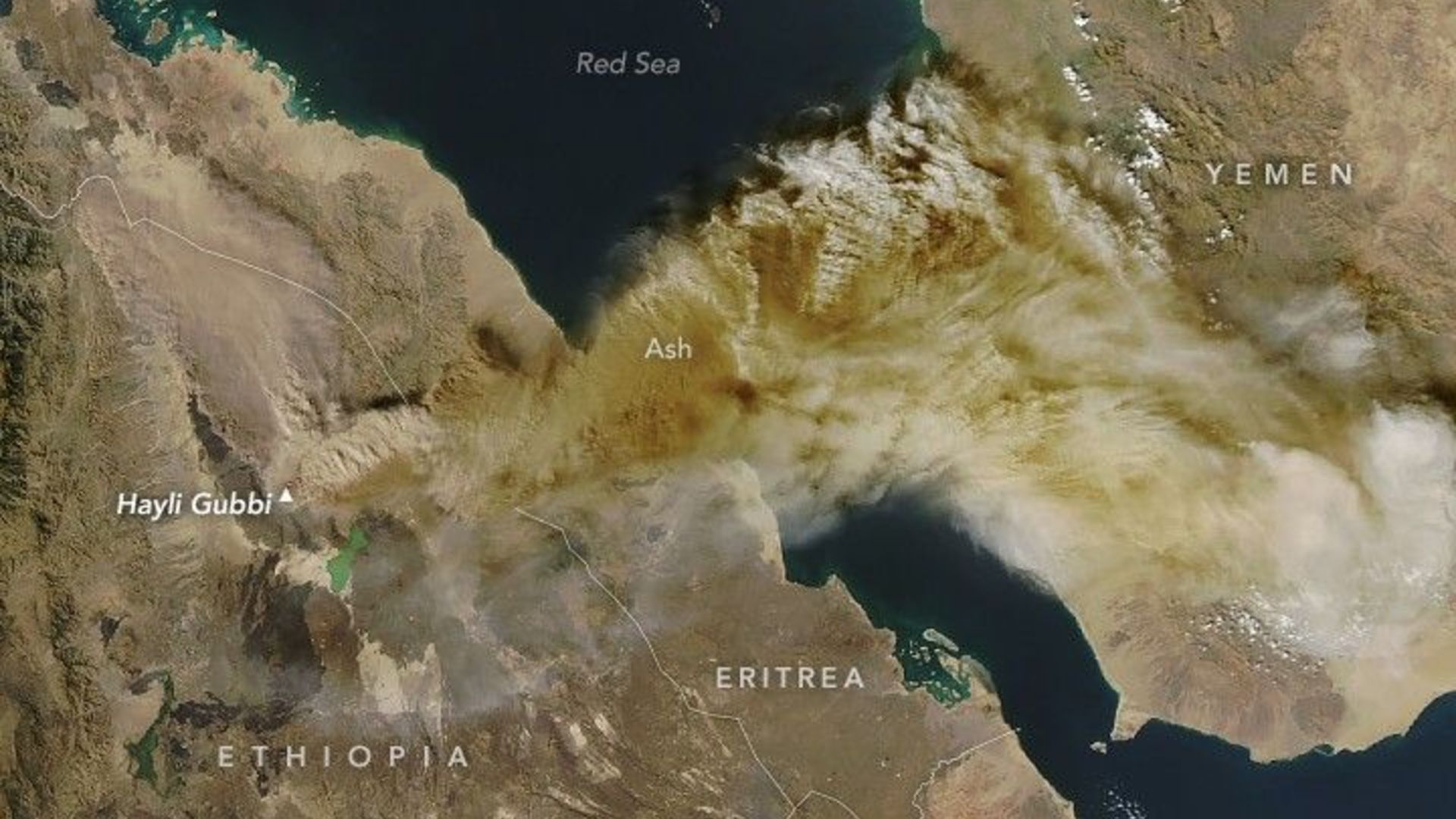

In late November, Hayli Gubbi erupted explosively, sending a towering plume of ash and volcanic gases high into the atmosphere. The MODIS instrument on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured the dramatic scene just four hours after the eruption began….

Satellite watches volcano spew ash over Middle East photo of the day for Dec. 16, 2025