In the fall of 1928, Alexander Fleming returned from a holiday to his lab at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, where he was conducting experiments with staphylococcal bacteria. In an uncovered culture by an open window, he noticed mold colonies growing that seemed to be killing off the surrounding bacteria. He later determined it wasn’t the mold—a strain of Penicillium—but a “juice” it produced that killed the bacteria. He dubbed the substance penicillin.

In his petri dishes, Fleming found that penicillin could knock out the bacteria that cause diseases like scarlet fever, pneumonia, gonorrhea, meningitis, and diphtheria. But he struggled to isolate and purify the drug for clinical use.

A decade after his discovery, a team of Oxford researchers did just that, conducting experiments in mice and then, in 1941, on a British police officer covered with abscesses. The drug was astonishingly effective in just 24 hours—but the small amount of available penicillin ran out before the infection was fully treated, and the officer died a few weeks later.

Penicillin remained in short supply—so short that it was sometimes extracted from patientsʼ urine to be reused.

That changed later in 1941 when the Oxford scientists traveled to the U.S., where government scientists led a wartime effort, alongside pharmaceutical companies, to scale the drug, ultimately developing a fermentation method that dramatically expanded production.

In the late 1940s, the nascent UN and WHO pledged to spur penicillin’s global production and distribution, funding equipment and training around the world. At the same time, the drug’s growing availability spurred its overuse and misuse, an issue Fleming had anticipated.

Accepting the Nobel Prize for his discovery in 1945, he warned that “the time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops.” He gave the example of a hypothetical Mr. X, who had a sore throat and used enough penicillin to “educate” the Streptococci to resist the drug, but not enough to kill the infection. He then passed it on to his hypothetical wife, who died from the drug-resistant infection.

“Moral: If you use penicillin, use enough,” he said.

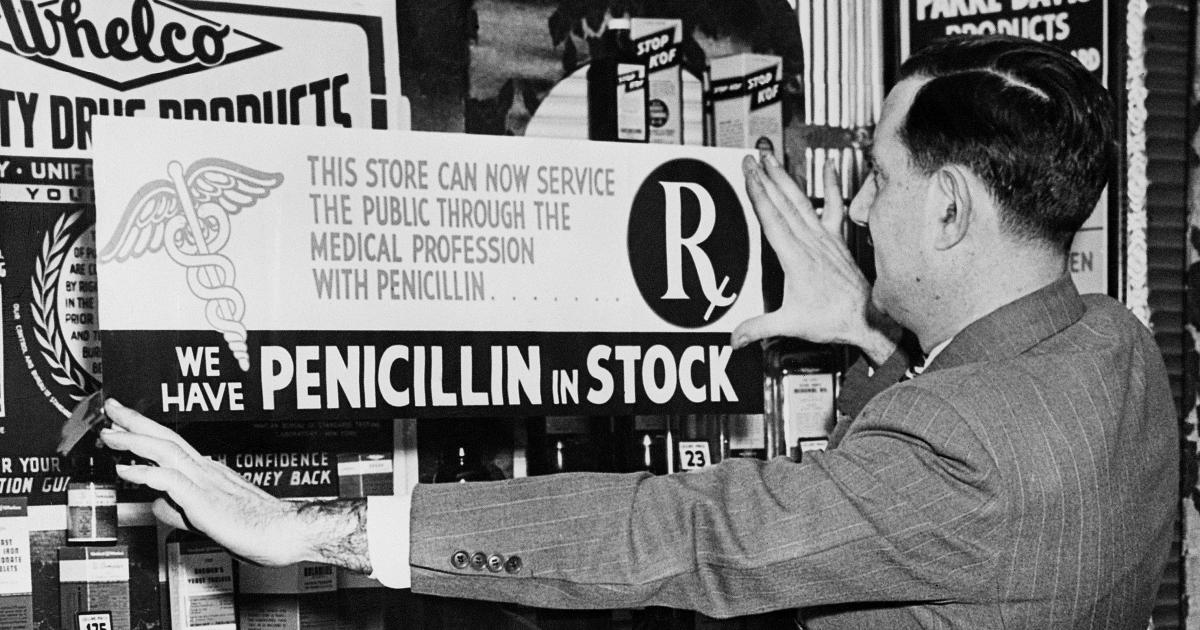

The warning went unheeded. Penicillin became widely available in a plethora of forms. It even turned up in cosmetic creams.

But it was the golden age of antibiotic discovery, and dozens of new antibiotics emerged from the 1940s through the 1960s, including methicillin, streptomycin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and vancomycin. “Clinicians and patients thought that we would always be a step ahead” of the bacteria, says Scott Podolsky, MD, director of the Center for the History of Medicine at Harvardʼs Countway Library.

For a while that was true. The development of novel antibiotics largely kept pace with demand. Pharmaceutical giants were excited by antibioticsʼ promise and made significant R&D investments to get them to market.

In 1961, the first reports of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus emerged, followed in 1967 by penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae. The list has grown over the decades.