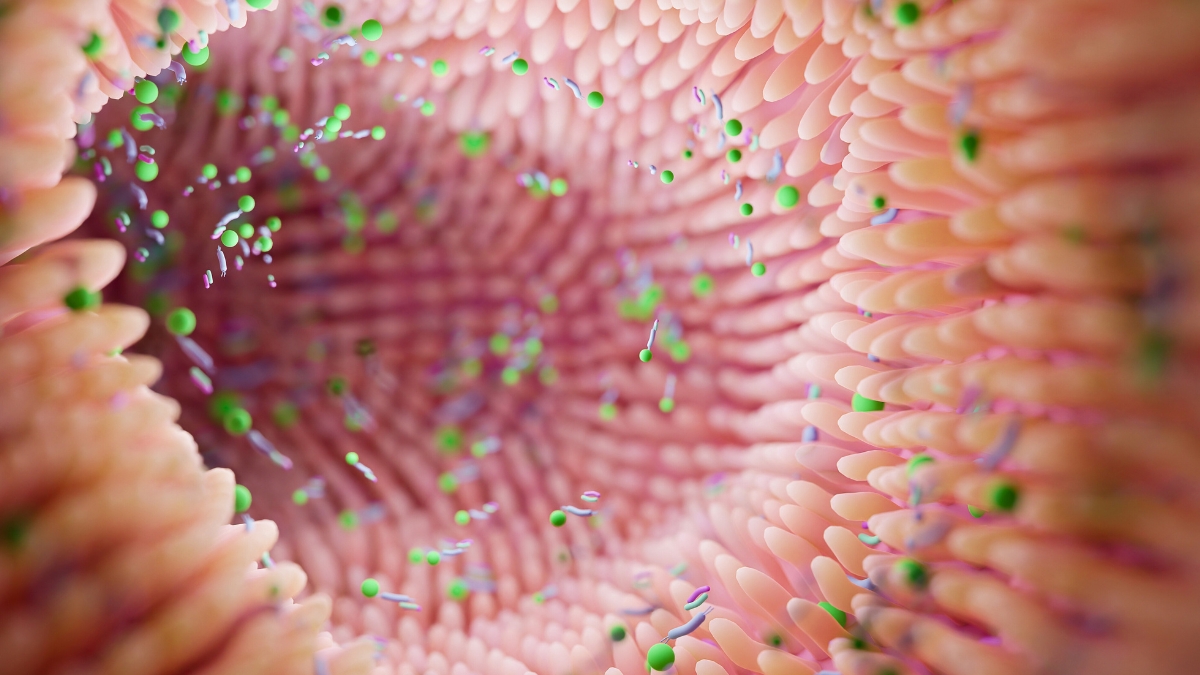

Precise changes in the connectivity between neurons caused by an imbalance of gut bacteria may help explain depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder, a new animal study suggests.

Researchers from Zhejiang University in China used fecal…

Precise changes in the connectivity between neurons caused by an imbalance of gut bacteria may help explain depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder, a new animal study suggests.

Researchers from Zhejiang University in China used fecal…