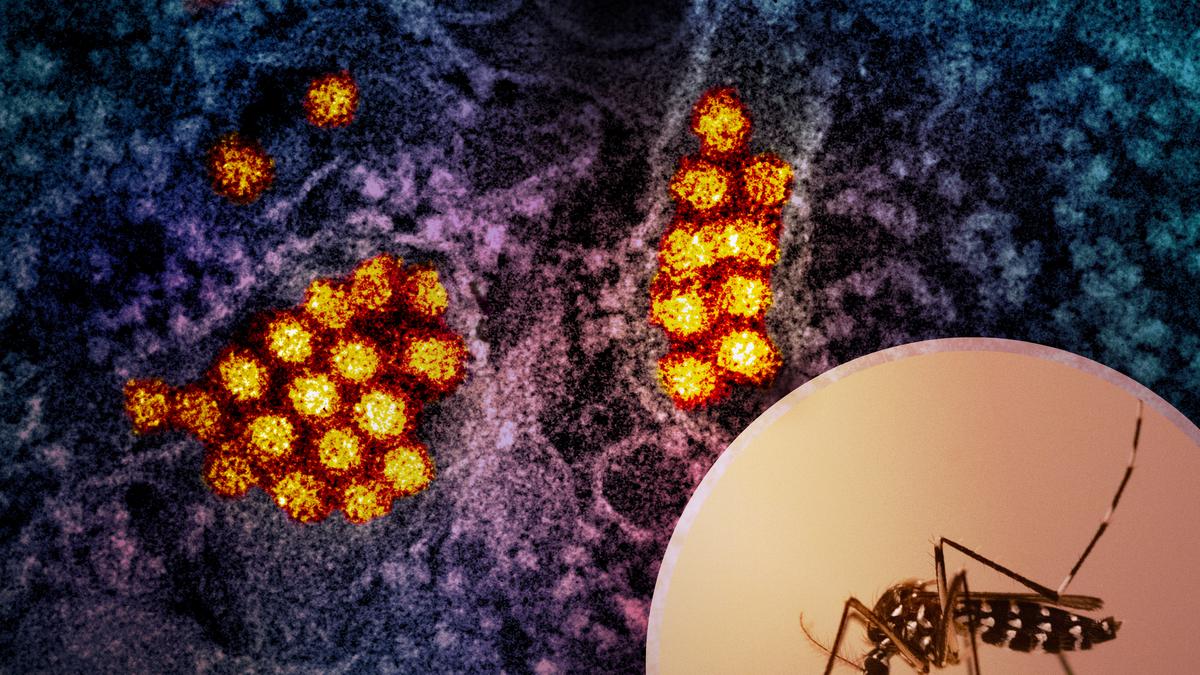

Mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue fever are an increasing threat to global health. Rapid urbanisation and climate change have created ideal conditions for mosquitoes to breed — while expanding global travel has accelerated the spread of these infections to new regions and populations.

A new study published last week has now added an unexpected twist to this story. Researchers have found that waning immunity against infections of the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) can predispose individuals to more severe dengue. The finding highlights the complex interplay between related viruses and suggests a potential strategy to beat severe dengue through timely booster doses of the JE vaccine.

Both Japanese encephalitis virus and dengue virus belong to the same genus, Orthoflavivirus. Previous research had hinted at interactions between JEV immunity and dengue outcomes. To understand more, the present study, involving researchers from Singapore, Nepal, and the US, examined three large dengue outbreaks in Dharan in Nepal between 2019 and 2023.

Nepal provided a unique setting: the country has high population immunity against JE due to a successful vaccination program launched in 2006 — yet until recently, it had very limited exposure to dengue. This made it possible to study how JEV immunity alone might influence dengue outcomes. Prior exposure to dengue itself is known to increase the risk of severe disease through antibody-dependent enhancement: where antibodies from a first infection facilitate viral entry during subsequent infections.

But in Nepal’s largely dengue-naïve population, the impact of JEV immunity could be specifically isolated.

Striking results

For the study, the research team recruited dengue patients aged 15 to 65 years early in their illness, i.e. within three days of fever onset, confirmed by rapid diagnostic tests (NS1 or DENV IgM). The study spanned five years and included three major dengue outbreaks, in 2019, 2022, and 2023. In total, 546 patients were enrolled and their blood samples were tested for viral serotypes, immune markers, and a biomarker called chymase. Chymase is an enzyme released by mast cells during inflammation, and it has been consistently validated in earlier studies as a marker of severe dengue. Its levels have been found to be elevated during both the acute and defervescence phases of the illness.

The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine on September 3, were striking.

Approximately 61% of patients had pre-existing antibodies that neutralised JEV, reflecting Nepal’s relatively high level of immunity against JEV. Individuals with confirmed JEV immunity showed significantly higher concentrations of chymase compared to JEV-naïve patients.

Further analysis revealed that this effect was primarily associated with mid-range — not too low, not too high — anti-JEV antibody titres of 1:160. Patients with these titres had significantly higher chymase levels compared to those with titres of 1:10 or 1:40. Notably, this correlation was not observed when anti-JEV ELISA titres were used, possibly reflecting cross-reactivity between DENV-specific antibodies and JEV in ELISA-based assays.

The association between mid-range JEV neutralising antibody titres and severe dengue was also reflected in clinical outcomes. The fraction of patients diagnosed with either dengue fever with warning signs or severe dengue, according to the WHO classification, was significantly higher among those with titres of 1:160 compared to patients without JEV immunity.

These individuals had a 3x higher risk of developing dengue fever with warning signs. Importantly, most participants were experiencing primary dengue infections, with only 7-10% showing evidence of prior exposure.

These findings isolated the role of JEV immunity in shaping disease outcomes. Even after excluding cases of secondary dengue, the results remained unchanged, strongly supporting the conclusion that JEV immunity alone is sufficient to modulate dengue severity, independent of prior DENV exposure.

Echoes from other flaviviruses

These findings echo earlier observations in studies of Zika and dengue viruses, where moderate antibody levels sometimes enhanced the viral infection of immune cells and worsened disease — while very high titres were protective. This is to say, as antibody levels wane over time, populations may enter a vulnerable “middle zone” in which immunity is insufficient to protect but strong enough to enhance disease.

The implications are significant for Asia, where JEV vaccination is common and dengue is spreading, and for the complex and connected nature of public health in a globalised world.

Specifically, the study showed that rising temperature and extended monsoons have caused the epidemiology of dengue fever to change rapidly, with increasingly bigger outbreaks in areas where there used to be only sporadic cases. Such regions include India, which is also facing similar kinds and levels of climate change. Thus, the authors suggest, the country needs to be ready with appropriate strategies to deal with the new challenges that will sprout as a result.

Second, while the study clearly showed that moderate titres of neutralising antibodies against JEV can worsen outcomes with dengue fever, it doesn’t undermine the importance of JE vaccination per se. Such vaccination has successfully lowered the incidence of JE in the population.

The findings of previous studies have shown that the titres of neutralising antibodies against JEV wane after a few years of vaccination. After five years, for example, only around 63% of vaccinated individuals still have neutralising antibodies against JEV. Thus, the new study strongly suggests the need for suitably timed JE vaccine boosters, which could serve the dual purpose of maintaining durable immunity against JE for longer periods and protecting the population against the risk of dengue fever with warning signs and severe dengue (due to waning titres of anti-JEV antibodies).

Third, the study reinforces the importance of chymase as a biomarker of dengue fever with warning signs and severe dengue, making it a convenient tool for physicians handling the uncertain trajectories of dengue fever.

Viruses respect no borders. The new study provides critical insights into how waning immunity against one flavivirus can worsen outcomes of another. Strategically timed JE boosters could be a valuable tool not just in sustaining protection against encephalitis but also in mitigating the severity of dengue — a disease whose burden is rising sharply across Asia.

Such remarkable work ultimately underscores the importance of integrated, forward-looking approaches in infectious disease control, with insights that could save countless lives.

Puneet Kumar is a clinician, Kumar Child Clinic, New Delhi. Vipin M. Vashishtha is director and paediatrician, Mangla Hospital and Research Center, Bijnor.

Published – September 18, 2025 05:30 am IST