Study setting

Public health response

As of 2023, the population in Norway was 5.5 million persons, 16% of whom were born outside Norway. Testing and health services for HIV are free of charge, regardless of legal status. A wide range of groups are recommended testing [9]. Several actors offer information, support and/or low threshold testing to key groups at risk of HIV acquisition [10], for example anonymous peer-to-peer rapid diagnostic testing for MSM since 2012 [11]. Refugees and asylum seekers from high-prevalence countries are recommended to be offered testing by healthcare services as part of a routine health check three months after arrival [12]. All pregnant women are offered testing in the first trimester. Since 2016, national clinical guidelines have recommended antiretroviral treatment of all persons diagnosed with HIV, regardless of CD4 count. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been available and publicly funded since January 2017. The number of PrEP users has increased steadily, reaching 3,500 in 2024 [6]. This is among the highest rates per capita in the EU/EEA, although the PrEP need in Norway is uknown [7]. Needle and syringe programmes for people who inject drugs (PWID) have been available since 1987 and opioid agonist therapy since 1998. Coverage of these two harm reduction interventions exceeds global targets for the elimination of HIV and viral hepatitis as public health threats [2, 13].

Trend in HIV diagnoses

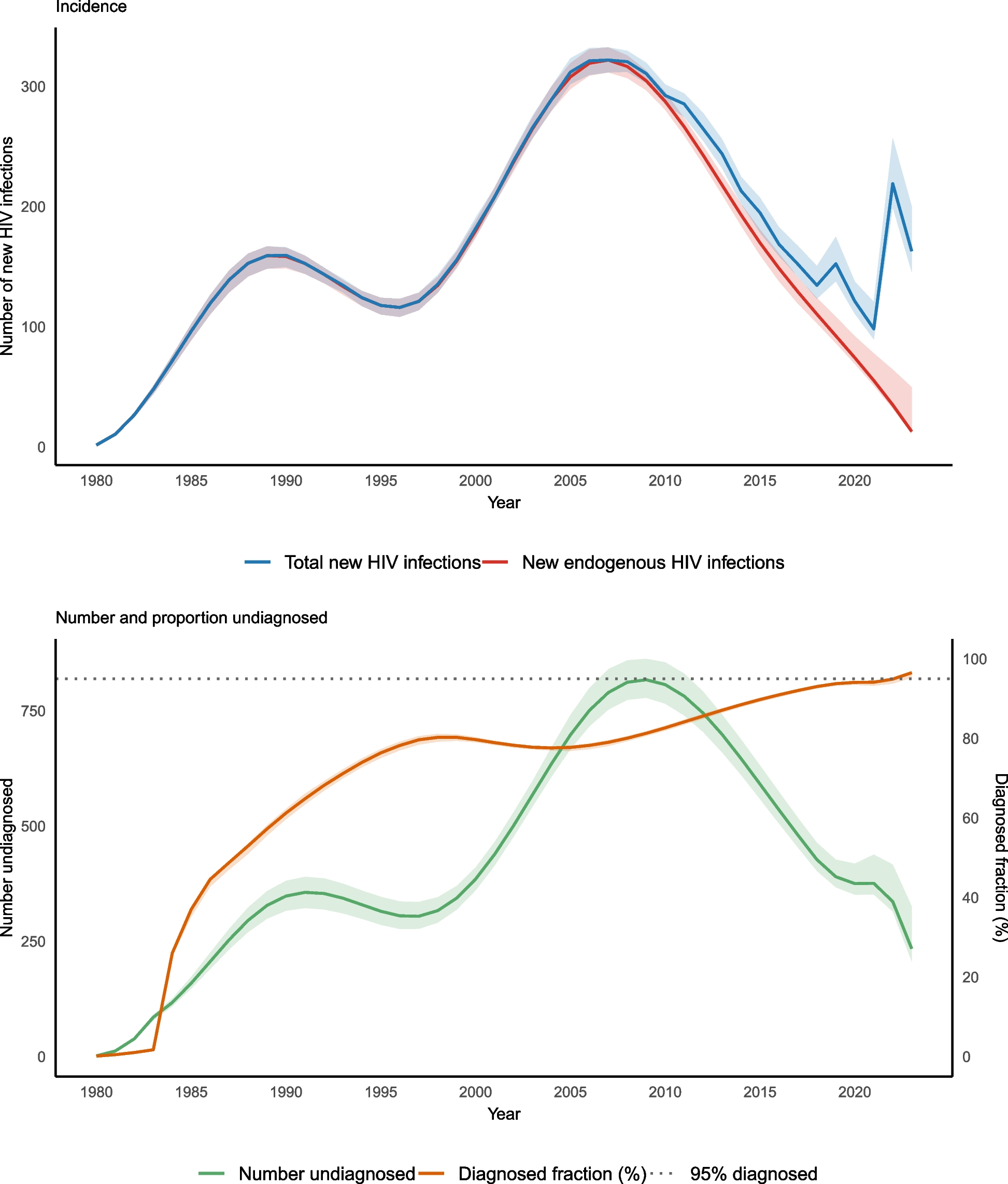

The HIV epidemic in Norway was initially characterised by diagnoses of HIV infection among MSM and PWID in the mid-1980s. Diagnoses peaked in the mid-2000s, driven by increased migration from high-endemic areas, such as sub-Saharan Africa, and an increase in diagnoses among MSM. From 2008 to 2021, there was a declining trend among both Norwegian-born MSM and migrants infected through heterosexual transmission. From 2020–2023, there were < 60 new HIV diagnoses annually among people reportedly resident in Norway at the time of HIV infection, with < 30 reportedly acquiring HIV in Norway. An increase in HIV diagnoses in 2022 and 2023 was driven by the arrival of 72,000 refugees from Ukraine [6].

Among persons newly diagnosed with HIV, the proportion born outside Norway has increased gradually from < 40% before the year 2000, to around 60% from 2000–2019 and 84% from 2019–2023. Up to 2023, over 80% of all new HIV diagnoses among migrants have been reported by the notifying clinician to have acquired HIV before migration to Norway. This proportion was 80% from 2011–2021, and 92% from 2022–2023. Further details are available in national surveillance reports [6].

Data sources to identify new HIV diagnoses

Norwegian surveillance system for communicable diseases

In Norway, cases of HIV infection have been mandatorily notifiable by clinicians and laboratories to the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases (MSIS) since 1986. The case definition is in line with the EU definition [14]. Data were reported anonymously (without national identity number) until 22 March 2019. Data on CD4 count at diagnosis have also been registered since March 2019, with completeness increasing from 45% in 2019 to 76% in 2020 and 96–99% in 2021–2023.

I included all notified cases of HIV-1 infection from 1987–2023 with data on diagnosis date, age, sex, mode of transmission, country of birth, known previous positive test before diagnosis, concurrent AIDS at HIV diagnosis, CD4 count, and death and out-migration.

Norwegian patient registry

Notified cases of HIV infection with a national identity number were only available in MSIS from 2019. To get a linkable cohort of persons with newly diagnosed HIV prior to 2019, I used the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR). In Norway, linkage to specialist care after HIV diagnosis is high, with treatment uptake reportedly 95% – 98% [15, 16]. NPR contains data on all inpatient and outpatient hospital stays, with national identifiers collected for all patients since 2008.

I identified patients with somatic hospital stays from 2011–2018 with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) code for HIV (B20 – B24 or Z21) registered at least twice. I included data on consultation date, age, sex and ICD-10 code. The supplement, part 1 further details the choice of this sample and compares new HIV diagnoses in MSIS and NPR over time.

Model input dataset

The model dataset included HIV diagnoses from MSIS from 1987–2010, NPR from 2011–2018 and MSIS from 2019–2023. The start year (1987) was chosen to avoid the early peak in HIV diagnoses before this year, related to the introduction of HIV testing [8].

For people diagnosed with HIV who had a linkable national identity number registered (NPR: 2011–2018, 100% linkable; MSIS: 2019–2023, 82% linkable), I supplemented these with AIDS notifications from MSIS (reported nominatively and separately from HIV notifications to MSIS since 1983 [6, 14]) and ICD-10 codes for specific AIDS-defining illnesses in NPR. These ICD-10 codes and a comparison to AIDS notifications in MSIS are presented in the supplement, part 2. I also included data on the date of migration to Norway, residence status (for example, resident, died, out-migrated) and country of birth from the National Population Register [17].

Table 1 presents key data points in the model dataset and compares these to data from routine HIV surveillance data alone. Data on date of HIV diagnosis, age and sex was known for all people diagnosed with HIV. Country of birth was unknown for three. The model dataset had a higher number of people diagnosed with AIDS (808 vs. 593) and deaths/out-migrations (904 vs. 614) than routine HIV surveillance data alone. Among persons born outside Norway and diagnosed with HIV from 2011–2023, 84% had known date of migration.

Application of ECDC HIV modelling tool

I used the ECDC HIV modelling tool version 3.1.5 (3 April 2025), modelling from 1980–2023. I ran models for all PLHIV, persons born in Norway and migrants. I also modelled the four subgroups that constitute the majority of new HIV diagnoses in Norway [6] (Norwegian-born MSM, Norwegian-born heterosexual transmission, migrant MSM, migrant heterosexual transmission). I also ran models utilising routine HIV surveillance data from MSIS only, to explore how results varied, compared to the enhanced model dataset. Pre- and post-migration infections were estimated from 2011–2023. Further details on the input parameters, diagnosis matrix (which determines the shape of the diagnosis probability) and goodness of fit are presented in the supplement, parts 3, 4 and 5. Further details on the underlying model method are available in the model manual [4].

I reported on estimates generated for the incidence of new HIV infections, the number of PLHIV, the number of undiagnosed PLHIV and the diagnosed fraction. For incidence I described the estimated total number of new infections and the number of endogenous infections (i.e. excluding pre-migration infections). I used 100 non-parametric bootstrap iterations to determine 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), defined by the 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles.