Morin-based powder, derived from guava leaves, apple peel, and figs, can be gradually released using polymers and offers a potential substitute for antibiotics.

A powder formulated from morin, a natural compound found in guava leaves, apple and fig peels, certain teas, and almonds, demonstrated antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activity against the bacteria responsible for periodontal disease.

Researchers expect that delivering the substance through polymers for controlled release could support nonsurgical therapies and serve as an alternative to antibiotics in managing harmful microorganisms.

In laboratory experiments, scientists at the Araraquara School of Dentistry at São Paulo State University (FOAr-UNESP) in Brazil evaluated morin on a multispecies biofilm composed of different bacterial strains designed to mimic the disease’s impact on patients’ gums.

The results were published in the Archives of Oral Biology. The study was conducted by Luciana Solera Sales during her doctoral studies at FOAr-UNESP, under the supervision of Fernanda Lourenção Brighenti. FAPESP supported the study through a doctorate and a research internship abroad.

Other researchers involved in the study included Andréia Bagliotti Meneguin from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences of Araraquara (FCFAr) at UNESP; Hernane da Silva Barud from the University of Araraquara (UNIARA); and Michael Robert Milward from the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Birmingham in England.

Developing oral hygiene platforms

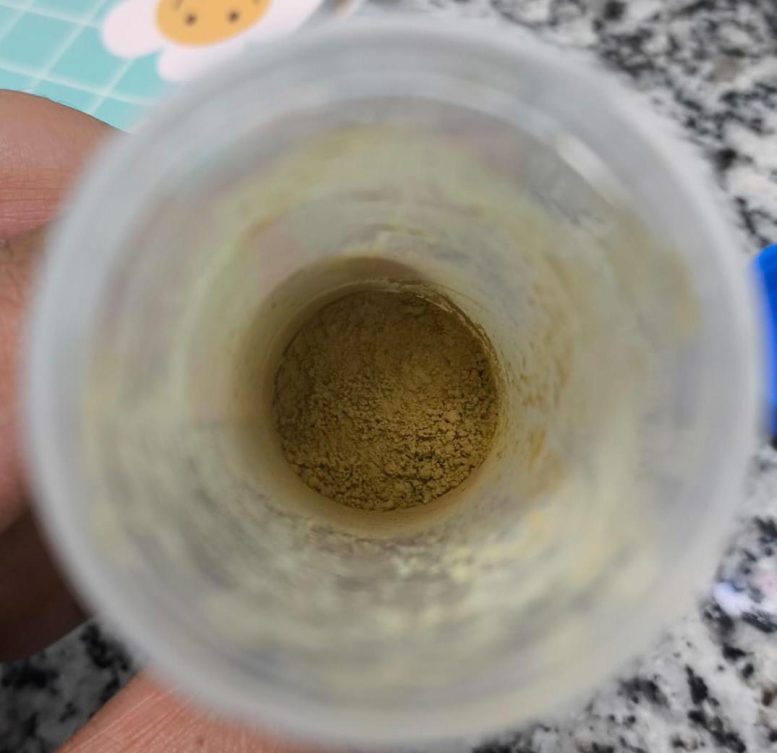

“At the moment, we have a fine powder obtained through spray drying – which is the same equipment used to make powdered milk – that can be used to make various types of oral hygiene products. The idea is to provide a platform that acts as an adjunct and can be useful, for example, for people with reduced motor skills who are unable to brush their teeth properly, such as older adults and patients with special needs,” says Brighenti.

Morin was chosen because it is a natural, inexpensive, and easily accessible compound.

“Morin is a flavonoid that can be obtained from various fruits. But simply eating it isn’t enough; the substance needs to be processed. The idea is to take advantage of this natural compound, its benefits, and its advantages, and transform it all so that it can be used to prevent and treat tooth decay and periodontal disease,” Sales points out.

Controlled release and product improvement

Brighenti and her colleagues have been developing what she describes as platforms that enable various substances to act on the diseases under investigation. She explains that this approach is important because most natural compounds do not dissolve easily in water.

“We have a constant flow of saliva. We produce, on average, 1 milliliter of saliva per minute. Anything we put in our mouths is quickly removed by saliva, especially because it has a smell and taste, which stimulates salivary flow. When we have something that sticks to the mucous membrane of the mouth, the inside of our cheeks, and our teeth, it gives us an additional advantage. This controlled release also helps us control the toxicity and stability of the substance,” the professor explains.

In the case of morin, the challenge was to optimize what the group had developed thus far, making it more appealing to potential patients while developing something scalable for the industry.

“We also aim to provide an alternative to products currently available on the market that don’t meet the demand because they have some side effects reported by patients, such as taste changes and increased tartar buildup, as well as stains on the teeth with prolonged use,” Brighenti adds.

“We started developing these systems in the form of tablets, films, and microparticles. But until then, they were too large and unfeasible for oral use. In my PhD, we tried to improve these products by making them smaller. That’s why I developed this format, which looks like powdered milk. I prepared a solution containing sodium alginate and gellan gum to encapsulate morin in a controlled-release system, which is already widely used for drugs but isn’t yet widely used in dentistry,” Sales explains.

Global burden of oral disease

Periodontal disease develops when biofilm or bacterial plaque accumulates on the teeth. This sticky layer, made up of bacteria and food particles, can damage the gums over time.

Its advanced stage, known as periodontitis, ranks as the sixth most common chronic disease globally. Early symptoms may include bleeding, but as the condition worsens, it can eventually cause tooth loss.

Proper oral hygiene, including brushing, flossing, and using fluoride toothpaste, can considerably decrease this risk.

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2022, nearly half of the world’s population (45%) suffers from oral diseases, amounting to approximately 3.5 billion people.

The researchers plan to continue testing morin first in animal models and then in clinical studies to investigate its other properties.

“We observed with the naked eye that the in vitro biofilm treated with morin in the laboratory is less stained than when treated in its free form. So, it’s possible that there’s an advantage, that this system helps prevent tooth discoloration. We also need to test, for example, whether morin maintains the balance of the oral cavity, because we don’t want to eliminate all bacteria from patients’ mouths,” says Brighenti.

Reference: “Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial evaluation of morin” by Luciana Solera Sales, Benjamin Hewitt, Maria Muchova, Fernanda Lourenção Brighenti, Sarah A. Kuehne, Melissa M. Grant and Michael R. Milward, 24 June 2025, Archives of Oral Biology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2025.106343

Funding: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.