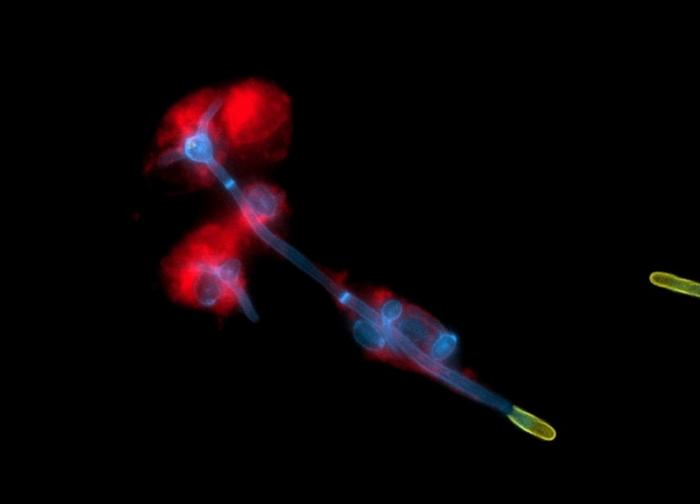

Candida albicans occurs naturally in the human microbiome and usually remains harmless. Under certain conditions, however, it can transform from its yeast form into thread-like hyphae and cause infections that can have fatal consequences, especially in immunocompromised patients. In this hyphal form, C. albicans produces the toxin candidalysin, a protein that directly attacks host cells.

Now, new research reveals that C. albicans not only uses the toxin candidalysin to cause infections, but also to colonize the oral mucosa inconspicuously—but only in finely balanced amounts. Too little toxin prevents oral colonization, too much triggers the immune system and leads to an inflammatory defense reaction.

The results were published in the journal Nature Microbiology in the paper, “Dynamic expression of candidalysin facilitates oral colonization of Candida albicans in mice.”

“We knew that the fungal toxin candidalysin can cause disease. What is new is that it is also necessary for the fungus to survive in the mouth,” explains Bernhard Hube, PhD, head of the department of microbial pathogenicity mechanisms at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology (Leibniz-HKI) and professor and chair of microbial pathogenicity at Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, Germany. “The yeast fungus Candida albicans uses the toxin like a door opener to anchor itself in the mucous membrane. As long as it only produces it in small quantities, it remains under the radar of the immune system and survives in the oral cavity in the long term.”

Two different Candida strains were compared: The aggressive laboratory strain SC5314 forms long hyphae and produces large amounts of candidalysin. As a result, the immune system reacts immediately with severe inflammation and eliminates the fungus after a short time. Strain 101, which occurs naturally in the mouth, produces only small amounts of the toxin and can thus remain inconspicuous in the mucous membrane without triggering a strong immune response.

“It is precisely these differences between the strains that show how important the fine regulation of candidalysin is for colonizing different niches in the body,” adds Tim Schille, PhD, a postdoc on the team. “Only if Candida albicans finds the correct amount, then the fungus can survive in the mouth long-term without being fought by the immune system.”

More specifically, the team found that “low-virulent strains of C. albicans expressed the candidalysin-encoding gene ECE1 transiently upon exposure to keratinocytes in vitro. In mice, ECE1 mutants were defective at accessing terminally differentiated oral epithelial layers where the fungus is protected from IL-17-mediated immune defense.”

Indeed, tight regulation of ECE1 expression prevented detrimental effects of candidalysin on the host. “It is remarkable how well the fungus regulates its activity,” says Schille. “This balance also explains why the toxin has been preserved evolutionarily: it enables the fungus to live permanently in the oral mucosa, but at the same time makes it dangerous as a potential pathogen.”