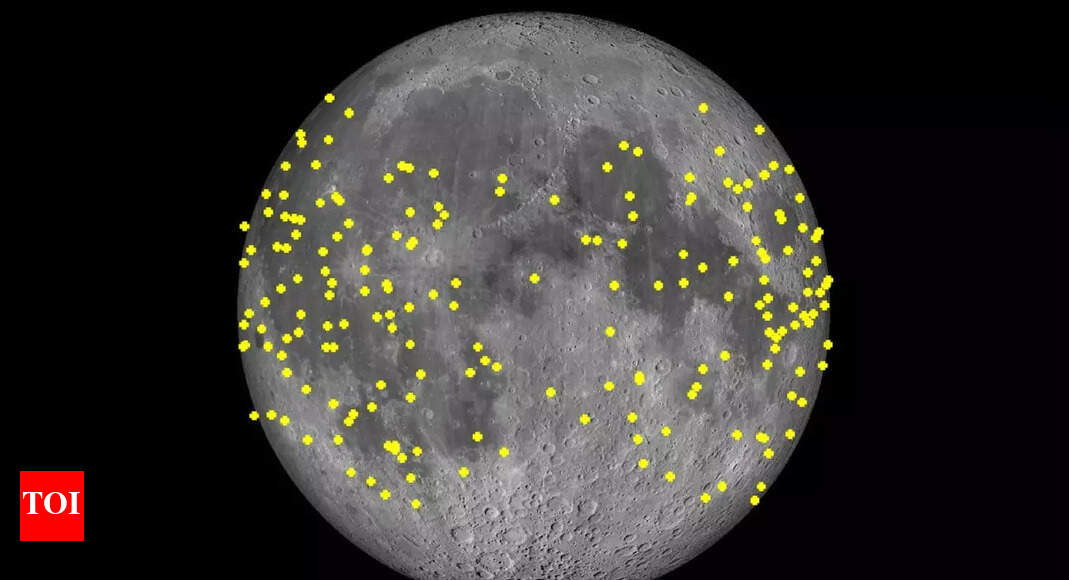

Astronomers have observed odd and strange lights on the Moon, or Transient Lunar Phenomena (TLPs), for centuries. These TLPs vary from bright, short flashes to weak glows and transitory colour changes, drawing the interest of observers across…

The Moon suddenly lights up? Strange flashes and glows still puzzle scientists around the world |