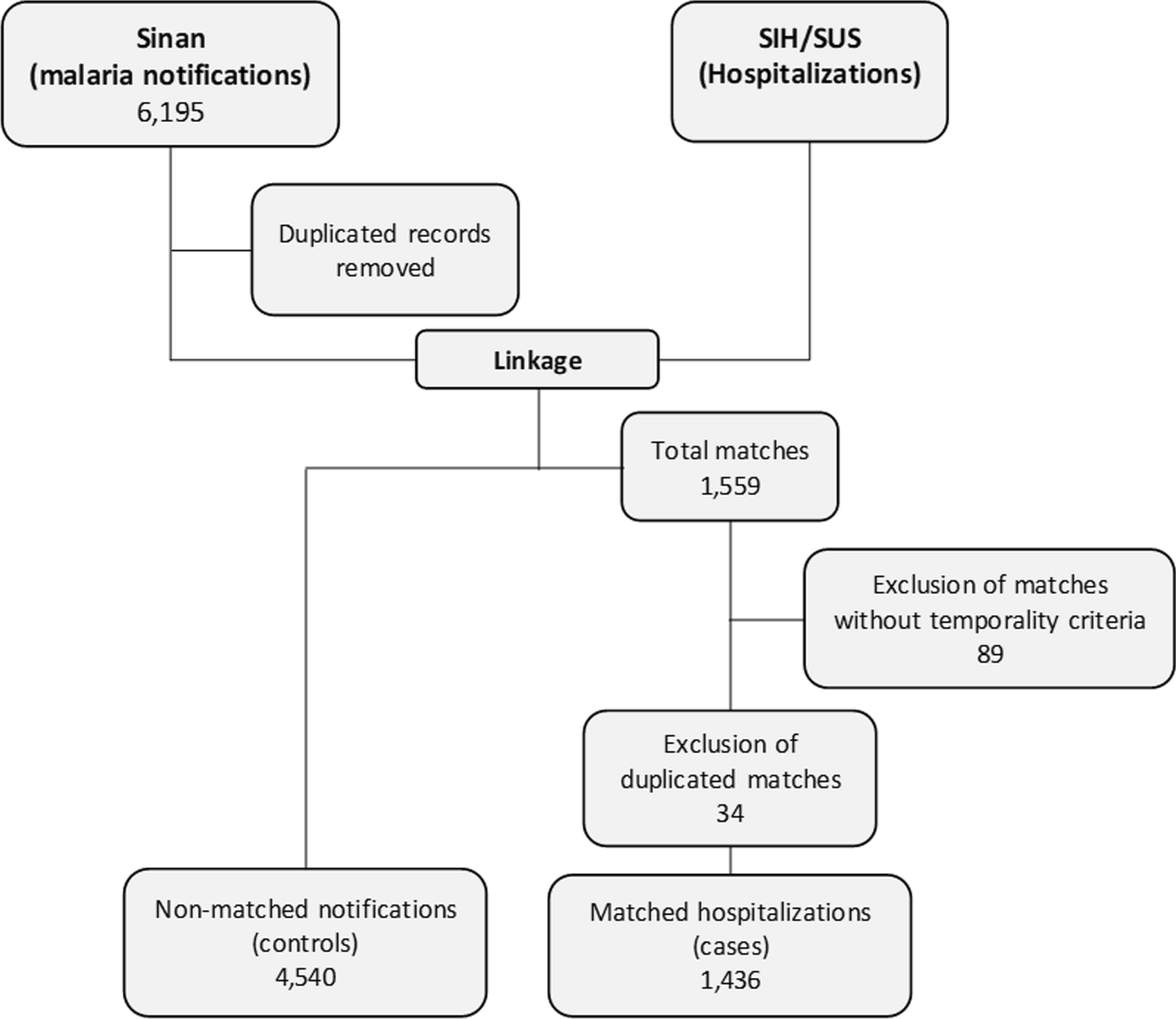

This study provides a significant contribution to understanding the factors associated with severe malaria hospitalizations in a non-endemic region, expanding the knowledge of the disease’s dynamics in areas with epidemiological patterns distinct from those observed in the Amazon Region. By addressing sociodemographic vulnerabilities, such as ethnicity, education level, and the origin of cases, the study identified critical gaps in the malaria surveillance and response system in the extra-Amazon Region. These findings hold practical and policy implications not only for Brazil but also for other countries facing similar challenges. On a global scale, the results offer an applicable model for malaria-free countries vulnerable to imported cases, supporting the development of adaptable strategies for surveillance, risk mitigation, and rapid outbreak response, ultimately contributing to the reduction of severe cases.

Approximately half of the malaria cases reported in Piauí from 2002 to 2013 were autochthonous. While imported cases occur are registered at the end of the rainy season, particularly in municipalities bordering Maranhão [23]. This trend was observed in hospitalizations originating from municipalities near the Maranhão border and from Maranhão itself. Regarding the high number of hospitalizations in Wenceslau Guimarães, Bahia, it was the result of an outbreak in 2018, which led to 50 confirmed cases, mainly within a settlement area [24].

It is important to understand that hospitalization is determined by medical criteria, not solely by clinical condition. Patients who are difficult to treat and more likely to relapse are hospitalized more frequently, as are children. In some cases, such as outbreaks like the one in Piauí, to prevent relapses and severe malaria cases, most patients are hospitalized until treatment is completed. Thus, not only the severity but also medical caution may be factors that lead to hospitalization in the extra-Amazon Region.

The profiles of hospitalizations in the extra-Amazon Region predominantly affected men, Black or mixed-race individuals, and those aged 20 to 39 years. In a study of Brazil’s Extra-Amazon Region, Garcia et al. [5] identified a similar profile. According to the authors, this profile is closely linked to socioeconomic factors, such as education, economic activity, and income, which are inherently related to social inequalities. The analyses indicated that patients with lower educational attainment (elementary or high school) were more likely to be hospitalized than those with higher education. A similar profile was found by Forero-Peña et al. [25] in Venezuela, which was closely related to economic activities.

There was also an association between hospitalization risk and Black or mixed-race ethnicity. According to Silva et al. [26], most of the Black population holds less-skilled positions with lower pay, lives in areas with limited infrastructure services, and faces greater restrictions in accessing healthcare. When this population does access healthcare, the quality and effectiveness tend to be lower, contributing to an increased risk of severe malaria cases.

According to Degarege et al. [27] in a meta-analysis conducted, low education levels are usually associated with low income and low-standard housing, which are linked to a higher risk of malaria, heavily influenced by the limited access to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention measures, often due to difficulty in accessing these services because of a lack of economic resources. Education is connected to occupational opportunities and improved life status, further increasing knowledge and access to information that promotes health and health services, leading to better acceptance of prevention practices carried out by the individual as well as those promoted by local health services. At the same time, it promotes higher income and better housing [27]. Moreover, the difficulty in accessing services, whether due to distance and transportation costs or low quality of the services, contributes to delays in treatment.

Proper and timely treatment of malaria significantly reduces hospitalization risk. The low incidence of malaria in the extra-Amazon Region makes its diagnosis challenging for local physicians, as it is not part of their routine practice [28]. For example, in Rio de Janeiro, a healthcare professional in an emergency department is 466 times less likely to identify a malaria case than a dengue case. Moreover, 55% of malaria cases treated at the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Diseases (a reference centre in Rio de Janeiro) were initially misdiagnosed as dengue during the first consultation [28]. The adjusted regression model showed that patients treated more than 48 h after symptom onset were more likely to be hospitalized, with increasing likelihood for delays of 3–7 days or 8 days or more. Nearly all severe malaria cases are caused by P. falciparum, while P. vivax and P. malariae rarely cause severe complications [29].

Active detection was protective against hospitalization compared to passive detection. This is closely linked to surveillance activities during outbreaks and patient follow-ups during treatment. The notification of autochthonous cases, which represent a risk of reintroduction and a sharp increase in cases in a short time, is an alert for healthcare services. This alert prompts temporary sensitization of local surveillance systems, increasing the detection of undiagnosed patients and follow-up of those identified through an index case. These actions improve timely diagnosis and, consequently, reduce hospitalization risk [5, 20]. The severity of the disease is intrinsically related to the level of parasitaemia, especially when it comes to malaria caused by P. falciparum, which is capable of infecting red blood cells of all ages, while P. vivax prefers young red blood cells [30]. Similarly, the level of parasitaemia results in symptoms arising from haematological changes and the immune response, which is usually higher in children without immunity to the disease [31]. Thus, case detection through active case finding is also a protective factor, as it can identify asymptomatic cases or those with few symptoms before they reach high parasitaemia that results in more severe clinical symptoms.

The Brazilian experience mirrors what occurs in other countries. For instance, in Australia, traveller movements occur constantly, with approximately 324 cases reported annually between 2012 and 2022, exhibiting a demographic profile similar to that observed in Brazil’s extra-Amazon Region, primarily men aged 20 to 39 years [32]. The main difference lies in the origin of imported cases, which reflect global trends. A high prevalence of P. falciparum cases is reported from African countries, whereas Australia has received the highest number of P. vivax cases, accounting for up to one-third of imported cases [32]. Nevertheless, imported malaria represents an ongoing threat to malaria-free countries due to the potential for reintroduction of transmission and the occurrence of severe cases requiring intensive care unit hospitalization. This risk is often exacerbated by diagnostic delays caused by a lack of clinical suspicion, which is influenced by determinants similar to those identified in Brazil’s extra-Amazon Region [32].

In the extra-Amazon Region, only 19% of malaria cases are treated within 48 h of symptom onset, compared to 60% in the Amazon Region, where malaria is more quickly suspected. Delays in diagnosis and treatment contribute to the higher proportion of severe malaria cases in non-endemic areas. Also, malaria fatality rates in the extra-Amazon Region can be up to 123 times higher than in the Amazon Region [8, 33].

In the context of global changes, climate change can directly or indirectly impact human health and malaria transmission. Long-term predictive models suggest that climate change will significantly affect efforts to eradicate malaria if environmental interventions do not continue, further increasing the population at risk for the disease [24, 34]. Furthermore, climate change may impact the achievement of the goals proposed by Brazil’s National Malaria Elimination Plan, which aims to eliminate autochthonous disease transmission by 2035 [35], potentially causing disease outbreaks in both the Extra-Amazon and Amazon Regions, as well as deaths resulting from severe cases.