To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to retrospectively evaluate the prognostic value of the ALBI score in ICU patients with cirrhosis and sepsis. We found that higher ALBI scores were significantly associated with increased 28- and 90-day mortality, and this association remained robust after adjustment for key demographic and clinical covariates. This trend persisted across both tertile and median-based stratifications, indicating a clear, dose–response relationship.

Mechanistically, the ALBI score is derived from serum albumin and bilirubin levels, reflecting both hepatic synthetic and excretory functions [20]. Albumin, a major hepatic protein, is a negative acute-phase reactant whose levels decrease during systemic inflammation, acute illness, and stress [21, 22]. In cirrhosis, hypoalbuminemia indicates impaired liver function and systemic inflammation driven by cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, which reduce albumin synthesis and increase catabolism [22]. This cascade contributes to vascular permeability, immune dysregulation, and multi-organ dysfunction [23, 24]. Conversely, elevated bilirubin reflects hepatic metabolic dysfunction and is often associated with cholestasis and severe liver injury. Moreover, hyperbilirubinemia may aggravate systemic inflammation through oxidative stress mechanisms [25]. Thus, the ALBI score effectively captures both hepatic reserve and inflammatory burden in critically ill patients with cirrhosis and sepsis.

Additionally, the gut-liver axis plays a critical role in the progression of both cirrhosis and sepsis [26, 27]. Increased intestinal permeability promotes bacterial translocation and endotoxemia, initiating systemic inflammatory response syndrome and subsequent multi-organ dysfunction [5, 28]. In our study, the ALBI score enabled risk stratification by dynamically reflecting this complex hepatic-infectious interplay.

Our RCS analysis demonstrated a nonlinear relationship between the ALBI score and mortality, with a marked increase in risk observed above specific threshold values. This data-driven pattern suggests that the ALBI score may serve as a useful early warning indicator for poor prognosis in ICU patients with cirrhosis and sepsis. While we proposed a preliminary inflection-based threshold derived from tertile stratification and RCS findings, we emphasize that this cutoff is exploratory and should be interpreted with caution until externally validated in prospective cohorts.Nevertheless, this preliminary threshold may help identify high-risk patients who could benefit from closer monitoring, more intensive supportive therapies, or expedited ICU admission.

To enhance clinical utility, we propose several potential pathways for integrating the ALBI score into practice. First, as a pre-ICU triage tool, the ALBI score could assist emergency department or general ward clinicians in identifying patients with liver dysfunction and systemic inflammation who are at elevated risk and may require early transfer to intensive care.Second, the ALBI score could be incorporated as a complementary parameter into existing risk models—such as SOFA or MELD—to improve liver-specific prognostic precision, especially in patients with sepsis-related hepatic impairment.Lastly, the ALBI score may support early treatment escalation decisions in ICU settings by serving as a simple, objective measure of hepatic reserve. Future research should aim to determine optimal ALBI thresholds for guiding clinical interventions, define appropriate time points for reassessment, and evaluate whether ALBI-based risk stratification translates into improved outcomes. These steps will be crucial in transitioning the ALBI score from a statistical prognostic marker to a clinically actionable tool.

Compared to traditional ICU scores such as SOFA and MELD, ALBI offers a simpler and more liver-specific assessment. The SOFA score includes only bilirubin for hepatic function and omits synthetic capacity. MELD, originally designed to prioritize liver transplant candidates, incorporates INR, which may be affected by anticoagulation and not fully reflect sepsis-induced hepatic dysfunction [29, 30]. In contrast, the ALBI score focuses on two fundamental aspects of liver function and performed comparably or better than SOFA in predicting short- and long-term mortality.

In subgroup analysis, we observed a statistically significant interaction between diabetes mellitus and ALBI score. The association between ALBI and mortality was stronger in diabetic patients, potentially due to mechanisms such as hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance [31], along with hyperglycemia-induced inflammasome activation and elevated proinflammatory cytokines [32]. Diabetes-related immune dysfunction, including impaired neutrophil chemotaxis and macrophage phagocytosis [33], may further amplify vulnerability in this population. These processes could interact with cirrhosis-related immune impairment, exacerbating clinical outcomes in sepsis.

To validate robustness, we applied a median-based dichotomization in sensitivity analyses. This approach, while clinically intuitive, supported our main findings—higher ALBI scores were consistently associated with worse outcomes.

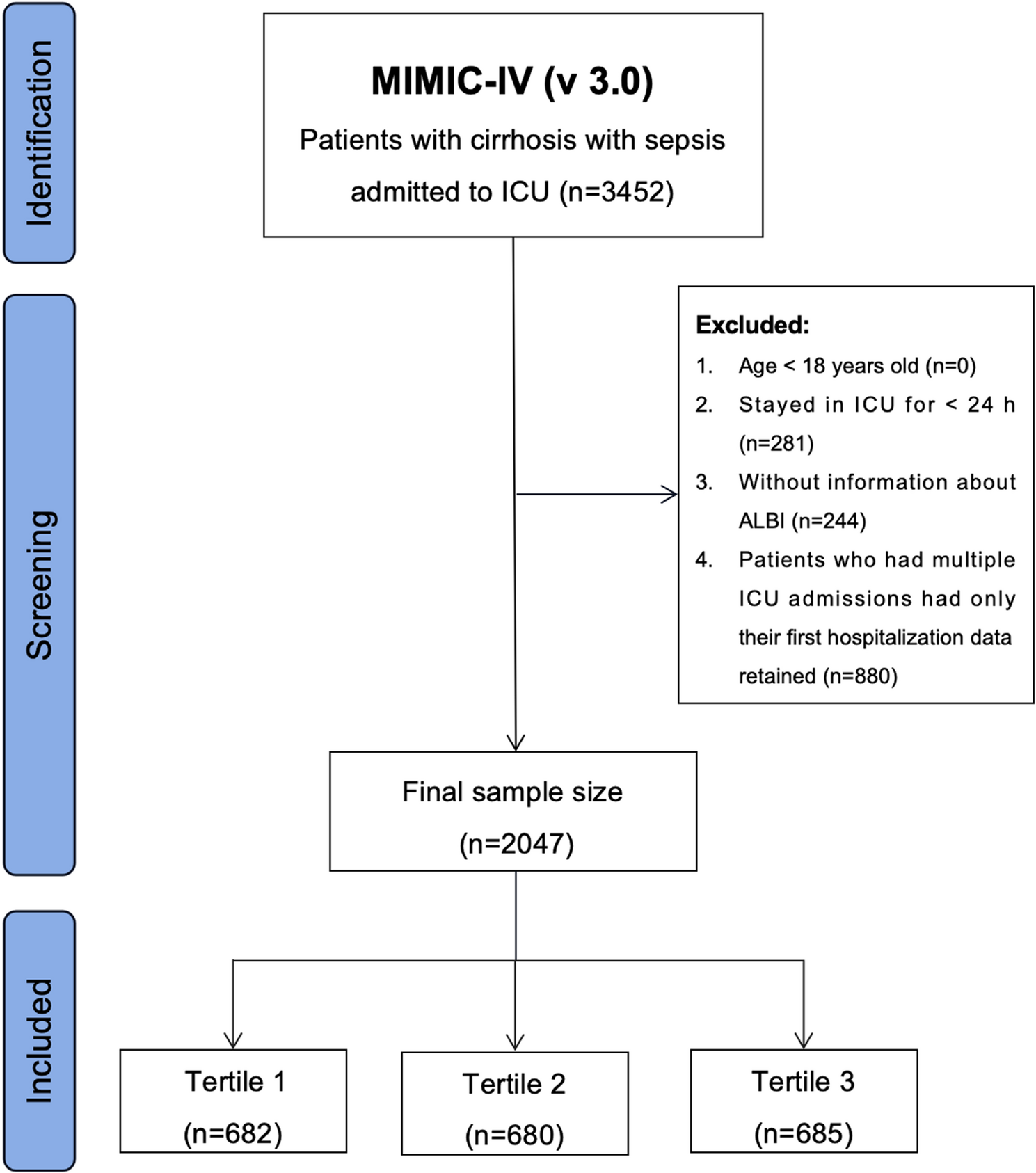

Despite the strengths of our study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this was a retrospective study based on data from a single tertiary care center, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other healthcare settings or populations. Although we employed rigorous inclusion criteria, multivariable adjustments, sensitivity analyses, and subgroup stratifications to enhance internal validity, the absence of external validation remains a notable limitation. Future prospective and multicenter studies, as well as analyses based on other publicly available critical care databases (e.g., eICU or HiRID), are warranted to confirm the applicability of our findings across broader clinical contexts. Second, patients with ICU stays shorter than 24 h were excluded, which might have led to an underestimation of early mortality risk, especially among patients who died shortly after admission. Third, ALBI scores were calculated based on laboratory parameters obtained within the first 24 h of ICU admission, without accounting for subsequent dynamic changes in liver function, which may also carry prognostic significance. Finally, although renal dysfunction was incorporated into the multivariate models, the neurological component of organ dysfunction could not be included due to substantial missing or inconsistent Glasgow Coma Scale data within the MIMIC-IV database. As the SOFA score already includes a neurologic assessment, we chose not to impute or supplement this domain separately to avoid potential multicollinearity. Nevertheless, this exclusion may have resulted in incomplete adjustment for overall disease severity.

In conclusion, the ALBI score is a simple, objective, and effective tool for early risk stratification in ICU patients with cirrhosis and sepsis. Its integration into ICU workflows and dynamic risk models warrants further exploration through prospective multicenter studies.