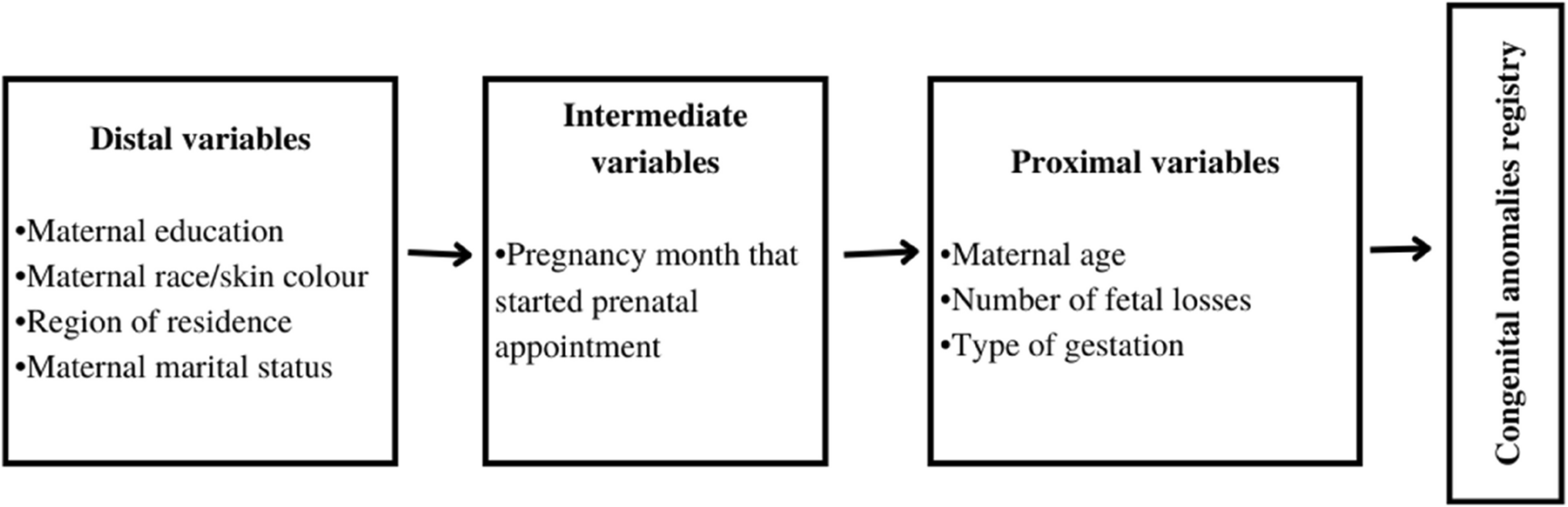

In this population-based study with more than 26 million live births the findings indicated that women belonging to the most vulnerable social group were exposed to a greater burden of factors that increased the likelihood of having a live birth with CA. However, the patterns of risk factors varied according to the group of anomalies. Maternal education was a risk factor only for neural tube defects, while lack of prenatal care and multifetal gestation were associated with greater odds of having a live birth with CA in all groups, except for those with Down syndrome. Advanced maternal age and previous fetal loss were the factors that increased the odds of CA in all groups.

Distal risk factors, known as socioeconomic factors, have been shown to increase the odds of children born with CA. Black maternal race/skin color and low education (0 to 3 years), increased the odds of CA by 16% and 8%, respectively. Similarly, Anele et al. (2022) reported that a low education level was associated with a 2.08 times higher risk of births affected by CA, mainly in mothers with higher incomes, indicating the impact of low education on the outcome [27]. Regarding black maternal race/skin color, studies carried out in the United States showed that the risk of birth with CA among African Americans varied according to the CA group, with a greater risk for musculoskeletal malformations and a lower risk for cardiac anomalies [28, 29]. Furthermore, in a study carried out in the southern region of Brazil, Trevilato et al. (2022) reported that black women had 20% higher odds of having children with CA than white women [6]. Both factors are related to greater social vulnerability and are consequently associated with low income [30, 31].

The contribution of socioeconomic vulnerability to CA has different origins, acts indirectly, and encompasses environmental conditions, such as poor nutrition, as well as social and structural conditions, e.g., lack of access to prenatal care [10, 11, 20, 32]. Thus, we observed that not having had any prenatal consultations during pregnancy or having started late has been shown to increase the odds of birth with CA. Trevilato et al. (2022) reported that women with no prenatal visits had 97% greater odds than women with seven or more prenatal visits of having children with congenital anomalies [6]. Prenatal care assistance allows important guidance on modifiable risks in the mother’s lifestyle, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes control, and exposure to certain teratogens, to be provided at an early stage of pregnancy, reducing the risk of births with CA [11].

Women in more vulnerable socioeconomic groups can find difficulties accessing prenatal care since women with lower incomes face barriers such as difficulty covering the cost of services, long waiting times, and difficulties obtaining transportation to reach appointment locations, which can lead to negative attitudes toward health care [33, 34]. Furthermore, Dingemann et al. (2019) reported that women with low education attend fewer prenatal consultations, in addition to having a greater chance of future complications in their children with CA [35]. The absence of prenatal consultations may be related to extreme socioeconomic vulnerability [36, 37]. Furthermore, it was observed that in Brazil, among women who underwent prenatal care, the largest proportion underwent (at least once) an ultrasound (99.7%). However, many congenital anomalies require other complementary exams for accurate diagnosis, which are often not available free of charge for the poorest population [38,39,40].

Neural tube defects were strongly associated with not having any prenatal consultations during pregnancy and low maternal education. Mothers exposed to these factors may not correctly supplement folic acid in the diet during the critical period of pregnancy in which neural tube development occurs (up to the fourth week of gestation) [27, 41]. It is recommended that supplementation begin as early as possible; ideally, supplementation should be started before pregnancy during conception planning, to reduce the likelihood of birth with neural tube defects [42]. Cui et al. (2021) reported that women with less education and who had unplanned pregnancies had less knowledge about folic acid and had higher odds of not starting to use it before becoming pregnant [43].

Additionally, there were significant variations in the odds of children being born with CA between regions of the country and CA groups. The leading cause of this variation is underreporting, and the Southeast is the region that best reports births with CA compared to others [7]. The greater chance of mothers living in the Northeast Region having children with neural tube defects has not yet been fully explained. According to a previous study, the Northeast and Southeast regions had the highest prevalence of neural tube defects [44]. The Northeast region of Brazil concentrates almost half of the Brazilian population living in poverty [45], which may help explain the greater odds of residence mothers of having births with neural tube defects, since this condition is highly associated with low income, low education attainment and poor diet (insufficient supplementation) [46, 47]. In addition, the Zika virus epidemic in Brazil in 2014 resulted in an increase in the reporting of live births with microcephaly and other congenital anomalies of the nervous system, especially in the Northeast region [5, 7], which may have contributed to the observed results.

The odds of having children with cardiac CA also varied widely between regions. Women who lived in the North and Northeast regions were less odds to have children affected by cardiac CA. This result reflects considerable underreporting of this group of CA across regions, which is more pronounced in the country’s poorest regions [7]. A similar result was observed by Salim et al. (2020), who reported fewer cardiac CA notifications in these regions [48]. Early diagnosis of cardiac CA may require a more complex structure than some centers can offer, in addition to trained professionals [49], which leads to underreporting of this group, which is more accentuated in the population and economically vulnerable regions.

Multifetal pregnancy and fetal loss were also associated with birth with CA. Previous fetal loss can be an indication of previous gestational problems, such as a fetus with severe anomalies. A history of prior anomalies has been shown in other studies to be a risk factor for birth with CA [6, 50], which, therefore, may be related to fetal loss in previous pregnancies. Furthermore, as noted by Al-Dewik et al. (2023), multifetal gestation increased the chances of birth with different types of CA, including cardiac CA and nervous system CA [51], as seen in the present work.

Maternal biological factors also demonstrated an association with the outcome. Thus, consistent with the literature, advanced maternal age was found to be the factor most strongly associated with the occurrence of births with Down syndrome, as already well known [52]. Additionally, advanced maternal age also elevated the odds of having children born with other CA, such as central nervous system defects and heart defects [52, 53]. The association between advanced maternal age and the risk of chromosomal defects and other CA has been widely recognized, it is seen that the CA risk varies by anomaly type and maternal age. It is worth noting that pregnancies in women under the age of 20 years have also been shown to increase the odds of births with CA, which is primarily attributed to social factors, as early pregnancy may be linked to low income and other lifestyle-related risk factors, such as the use of drugs and alcohol, as previously discussed [54,55,56].

A relevant aspect of this study was the extensive sample size, as it included all births evaluated nationwide over a long period. Additionally, through the linkage process, it was possible to include live births that were not reported in the SINASC database but were registered in the SIM database. Correcting an information error and substantially enhancing the case group’s size. However, it is important to emphasize that the CA recorded in the SIM were those that were severe enough to result in the individual’s death, which may introduce a bias in this regard. In addition, CA that were not recorded in the SINASC at birth and were not registered in the SIM, were not captured in the notifications and consequently were not included in the analyses. Several factors contribute to this underreporting, including the fact that some CA are not detected at birth because they are not noticeable. In addition, the health team is often not trained to recognize certain more important CA, a capability that varies among Brazilian regions, reinforcing the need for active surveillance of the most important defects [17, 57]. Furthermore, there was no information available on the use of folic acid during pregnancy, which made a more detailed analysis in this regard impossible.

In summary, this study showed that socioeconomically vulnerable women have an increased odds of having a pregnancy affected by CA, mainly for neural tube defects, due to the sum of the risk factors to which they are exposed. Maternal characteristics such as low education, region of residence, race/black skin color, and late start of prenatal care were associated with the outcome. Biological characteristics, such as advanced maternal age and multifetal gestation, were also shown to be strongly associated with birth with CA. Advanced maternal age had a strong association with birth with Down syndrome, whereas multifetal gestation was mainly associated with neural tube defects. Thus, although many CA are not preventable, primary care measures to reduce associated factors greatly impact preventing births with CA [58, 59]. As noted in this study, there is a great need to identify the factors associated with CA and outcomes at the population level, thereby supporting the establishment of effective public policies that can effectively reduce the incidence of preventable CA, as a broad-coverage support for families wishing to become pregnant, including genetic counseling for families with a history of congenital anomalies in the family, control of maternal infections before conception, nutritional support and folic acid supplementation before conception also, among others, in addition to health actions to monitor and care of those born and living with CA.