Subscribe now for full access and no adverts

Many ancient cultures around the world are known to have decorated their skin with tattoos, and evidence of this practice even survives on some mummified human remains. However, like modern tattoos, the ink used to create these images has a tendency to bleed and fade over time, and this is further accelerated by the decomposition of the body and other taphonomic processes after death. These changes over time make it difficult to determine the original forms of the tattoos, and consequently has an impact on their research potential.

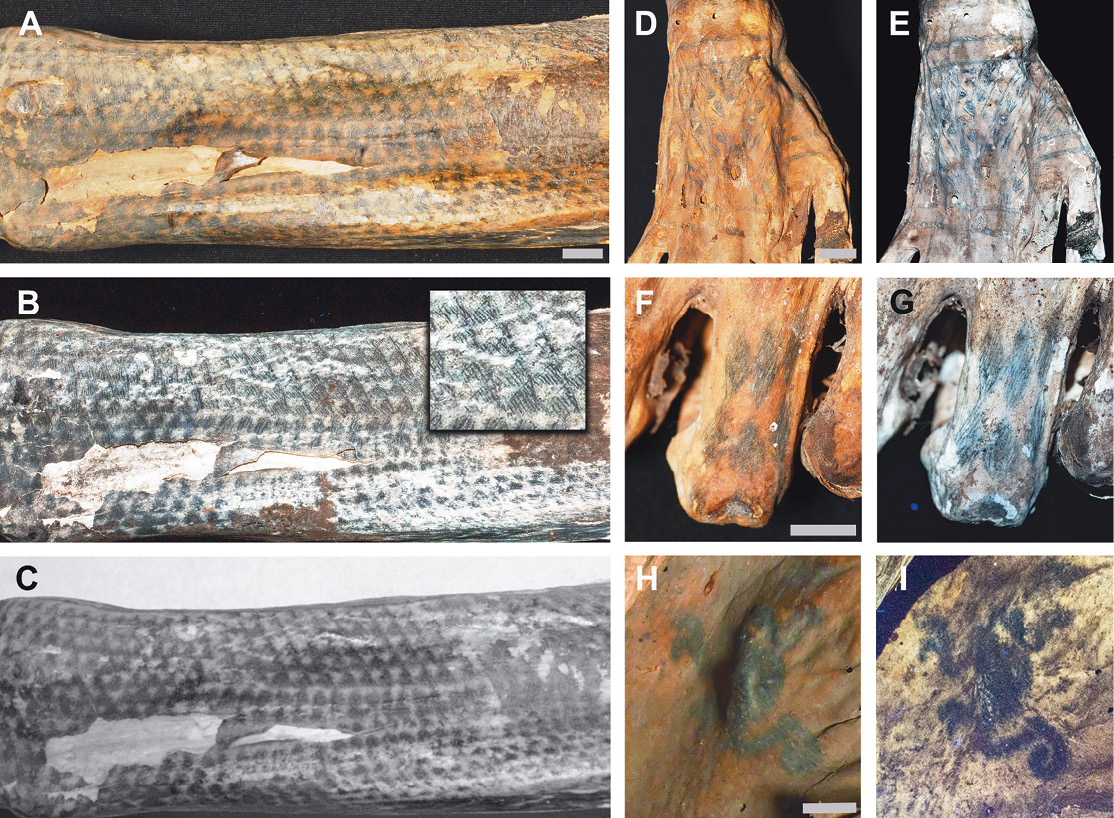

Previous examinations of ancient tattoos have used technologies such as infrared, which can help to identify very faint tattooed lines and even reveal tattoos that are otherwise hidden, but is less able to eliminate ink bleed that hides the original artwork of tattoos. The researchers behind a new paper in PNAS (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2421517122) therefore decided to try a different technique: laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF). LSF works by applying fluorescence to a sample, which makes the skin fluoresce or glow but does not affect the black ink of the tattoos, essentially backlighting these shapes. The results are then processed for image equalisation, saturation, and colour balance, creating a final product where the skin appears white behind the black outlines of the tattoo. This approach reveals ink densities within the skin itself, making it possible to see beneath blurred or bled ink on the skin surface, thereby revealing precise tattoo-markings as they once were.

The team applied this technique to a set of naturally mummified remains from the Chancay culture, a pre-Columbian civilisation that existed in coastal Peru between c.AD 900 and 1533. The Chancay were a small empire who produced a variety of crafts – they were particularly well known for their textiles – and had thriving trade relations with other cultures in the region. Like a number of other pre-Hispanic cultures in South America, they practised tattooing as a form of body ornamentation. The study analysed a set of c.100 human remains currently stored in the Arturo Ruiz Estrada Archaeological Museum at the José Faustino Sánchez Carrión National University in Huacho, Peru. These remains were unearthed in 1981 during rescue excavations at the Cerro Colorado cemetery in the Huaura Valley of Peru, near the modern city of Huacho. Demographic work is ongoing, but the sample studied encompasses a range of individuals including both men and women and representing several different age groups. Radiocarbon dating has not yet been carried out on the entire set, but the individuals tested so far date to the period AD 1222-1282. As the chronological framework improves, researchers hope to be able to say more about how Chancay tattoos changed over time.

As intended, the application of LSF to these samples revealed details of an array of tattoos. Of particular interest were a handful of individuals who were found to have incredibly fine tattoos, with lines just 0.1mm to 0.2mm wide – narrower than the width of a standard #12 modern tattoo needle (0.35mm) – perhaps made with an object like a single cactus spine or a sharpened animal bone. These tattoos most commonly comprise geometric designs featuring triangles, but others were also found, including several animal-like images. Each dot of the fine lines making up these intricate patterns would have had to have been placed carefully by hand, requiring immense control. The high skill level of the artists and the time that must have been invested in these tattoos, combined with the fact that they are relatively rare within the study sample, leads the researchers to suggest that they were restricted to subsets of the population such as, perhaps, particularly important members of society, or those involved in specific ceremonies. Other specimens bore more amorphous or poorly defined tattoos, but LSF was still able to define the features more clearly than previously possible, by increasing the contrast between skin and ink.

These findings offer valuable new information about the place of tattooing in pre-Columbian art and the culture of the Chancay. As part of the study, the researchers compared the tattoos to other Chancay art forms and found that some of the ultra-fine tattoos are more detailed than decorations on Chancay pottery, rock art, and textiles. This suggests that perhaps tattooing should be regarded as an art form of at least equal importance to these other crafts. The study also demonstrates the capabilities of LSF to reveal details of tattoos not possible with other methods and expand the scope of analysis. The researchers hope that it can be used to increase further our knowledge of early tattoos by studying even older examples in the future. This study builds on the application of LSF to a range of archaeological targets so far, from wall paintings and mosaic floors to ceramics and glass, suggesting that LSF has yet more to offer the field (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103475).

Text: Amy Brunskill / Images: T G Kaye, J Bąk, H W Marcelo & M Pittman, PNAS 2025; artefact from Arturo Ruiz Estrada Archaeological Museum Collection, T G Kaye, J Bąk, H W Marcelo & M Pittman, PNAS 2025