Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a severe form of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy that can lead to significant maternal and fetal morbidity. One of the rare but serious complications of HG is Wernicke Encephalopathy (WE), a neurological, potentially life-threatening condition caused by thiamine deficiency, which is essential for glucose metabolism [15].

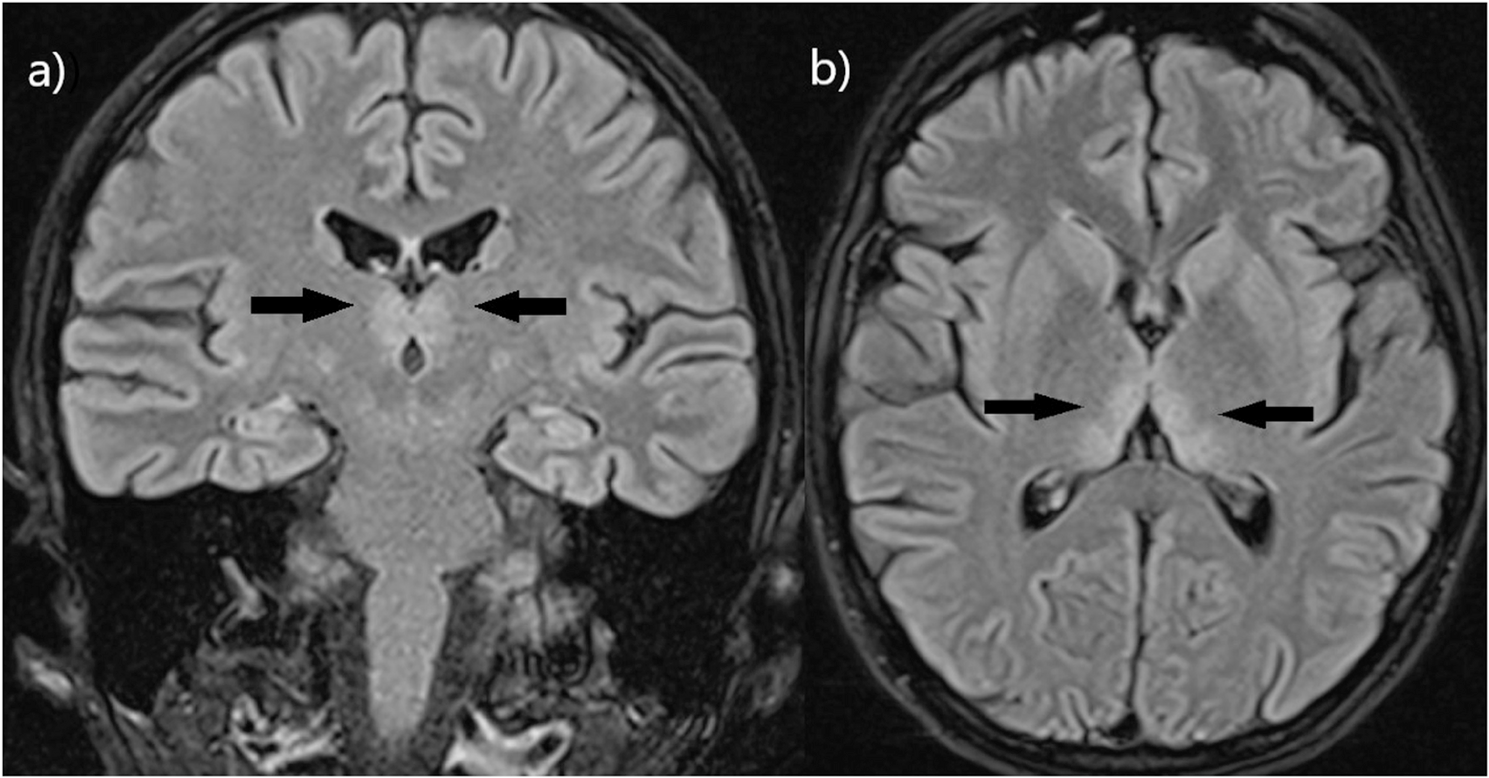

It is known that human neurons account for only 10% of brain cells, but are responsible for as much as 90% of glucose consumption in the brain. Since glucose is the main source of energy for neurons, thiamine deficiency impairs the utilisation of glucose as a substrate for neuronal energy metabolism, resulting in selective neuronal death. This causes oxidative stress, reduced ATP production, glutamate excitotoxicity, inflammation, lactic acidosis, impaired astrocyte function, and decreased neurogenesis — resulting in metabolic imbalance and neurological complications [16]. In the absence of supplementation, thiamine deficiency can develop within 2 to 3 weeks. Early manifestations of WE may include nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, memory impairment, sleep disturbances, and emotional lability. The classic clinical triad of ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, and altered mental status is only present in 16–20% of patients at initial evaluation, which further complicates timely diagnosis [15]. The diagnosis of WE remains based on clinical symptoms. There are no rapid, routine diagnostic tests for this condition. Blood thiamine levels can be measured, but there is no established threshold level that would be safe for patients before brain damage develops. Magnetic resonance imaging has high specificity but poor (53%) sensitivity and can therefore only confirm clinical suspicion of WE [16]. Non-specific clinical symptoms and rare occurrence make it difficult to diagnose WE, especially in pregnant women. The association between WE and hyperemesis gravidarum is well documented, therefore, caregivers of pregnant women must consider WE and treat this condition immediately in women reporting severe vomiting and inability to eat, as two to three weeks of unbalanced nutrition can lead to thiamine depletion and life-threatening complications. Awareness of possible predisposing factors and maintaining a high level of clinical suspicion are the best tools for early diagnosis, which is crucial for preventing neurological sequelae [17]. Prevalence data on Wernicke encephalopathy (WE) comes primarily from autopsy studies, which report rates ranging between 1% and 3%. Several studies have shown that clinical records tend to underestimate the true prevalence, as the diagnosis is often overlooked or missed. The incidence of WE is thought to be higher in developing countries, largely due to widespread vitamin deficiencies and malnutrition [15]. In the context of HG, thiamine deficiency is primarily related to insufficient intake and impaired absorption due to persistent nausea and vomiting, as well as the increased metabolic demands of the growing fetus and the hypermetabolic state of pregnancy [17].

Persistent vomiting in hyperemesis gravidarum significantly contributes to thiamine depletion, particularly in pregnancy, where maternal demands are elevated. Women with hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) are frequently dehydrated and suffer from significant weight loss, malnutrition, electrolyte imbalances, and vitamin deficiencies [17]. Malnutrition associated with WE in pregnancy is a rare but serious and preventable consequence of hyperemesis gravidarum, which requires attention due to its rapid onset and unfavourable course. Unfortunately, as reported by the authors of a systematic review, symptoms of WE are currently often overlooked or exacerbated by the administration of glucose, leading to poorer outcomes for the mother and foetus, which could have been avoided by the prophylactic administration of thiamine injections [2]. In our case, glucose-containing fluids were administered before thiamine supplementation as part of routine intravenous therapy for vomiting, at a time when thiamine deficiency had not yet been suspected. It is therefore possible that this contributed to the clinical manifestation of WE. This underscores the importance of empirical thiamine supplementation in pregnant patients at risk of deficiency, especially before administering glucose-containing fluids. Similar risks are observed in patients undergoing cancer treatment, where chemotherapy-induced nausea and poor intake can also lead to severe nutritional deficiencies. Other risk factors include bariatric surgery, prolonged intravenous nutrition without adequate supplementation, chronic hemodialysis, and magnesium depletion [9, 18]. Given that magnesium is a cofactor for thiamine-dependent enzymes, its deficiency can further impair thiamine utilization, increasing the risk of neurological complications. Diets high in carbohydrates or containing thiaminase-rich foods further heighten the risk. Moreover, chronic alcohol use, restrictive diets, or food consumption with thiamine antagonists are linked to impaired utilization of this essential nutrient. These complex interactions underline the multifactorial etiology of thiamine deficiency, which, if unresolved, may progress to severe neurological conditions such as WE and even further to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS). Although Wernicke Encephalopathy is classically associated with chronic alcohol use, recent evidence highlights its occurrence in various non-alcoholic contexts. Chamorro et al. demonstrated that non-alcoholic WE may differ in clinical presentation and is frequently underdiagnosed due to atypical or subtle symptomatology [19]. Moreover, Koca et al. reported a case of WE in a patient with cholangiocellular carcinoma, illustrating how persistent vomiting and malnutrition, even in the absence of alcohol use, can precipitate severe thiamine deficiency [20]. These findings align with our case and emphasize the need for heightened awareness and early intervention in at-risk non-alcoholic populations, particularly in pregnancy and oncology settings.

To address prolonged or severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, particularly in cases persisting beyond the first trimester, early screening for complications and timely intervention are needed in women. Identifying and addressing nutritional deficiencies, especially thiamine deficiency, should be a priority for midwives and women’s health providers [8, 9, 21]. This is crucial for preventing complications such as WE [21].

The use of a validated, clinically practical, and easy to use tool that measures severity of NVP, such as the Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis and Nausea (PUQE) scoring system (PUQE-12 or PUQE-24), can assist with monitoring progression and treatment. The PUQE scoring system is a validated tool for assessing the severity of NVP and can help guide management decisions. Despite its utility, it is not consistently applied in practice, potentially delaying recognition of severe cases [11]. In addition to PUQE scores, clinicians should be aware of red flag symptoms that warrant urgent intervention, such as persistent ketonuria, signs of dehydration, significant weight loss, electrolyte imbalances, altered mental status, or any neurological symptoms suggestive of thiamine deficiency.

Currently, there are no universally accepted guidelines specifying exact blood thiamine levels that should trigger therapeutic intervention. Given this, clinical decision-making should prioritize early recognition of symptoms and implementation of preventative strategies, rather than relying solely on laboratory-confirmed deficiency [22]. Reference values may vary between laboratories, and the interpretation of results should take into account the patient’s clinical status and symptoms suggestive of thiamine deficiency. In cases where thiamine deficiency is suspected, such as in hyperemesis gravidarum, chronic malnutrition, prolonged parenteral nutrition, or alcohol use disorder, early administration of high-dose thiamine is recommended, even before laboratory confirmation. While thiamine deficiency is typically defined as a blood thiamine level below 28 µg/L (2.1 nmol/L), a severe deficiency requiring urgent intervention is generally considered when levels fall below 7 µg/L (0.5 nmol/L) [11, 12, 22]. However, the presence of neurological symptoms consistent with WE (ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, confusion) should prompt immediate administration of 500 mg IV (intravenous) thiamine every 8 h for 3 days, followed by 250 mg IV daily for 5 additional days, in accordance with recent clinical guidelines [6, 9, 11, 12]. The presence of neurological symptoms is emphasized in the diagnostic criteria for Wernicke encephalopathy, as decreased thiamine levels alone is insufficient to establish the diagnosis [14]. Given the potentially irreversible neurological damage associated with thiamine deficiency, particularly in high-risk populations, preventive supplementation (oral 100 mg tds or intravenous as part of vitamin B complex) should be considered in individuals with prolonged vomiting, severe malnutrition, or other conditions predisposing to tiamine depletion [11]. Although there are recommendations for the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy, they are not specifically tailored to pregnant women. Existing guidelines for pregnant women in the context of hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) mainly focus on the prevention of WE. There are some case reports of WE in pregnancy with various doses of thiamine administered (ranging from 100 to 500 mg a day orally or intravenously) [9].

In instances where standard dietary and lifestyle measures fail to control symptoms, timely pharmacological intervention may be warranted. Pharmacological antiemetic therapy is still used with great caution by some patients and health care providers to treat NVP and is erroneously considered to be contraindicated in pregnancy [23]. However, substantial evidence supports the safety and efficacy of specific antiemetics, such as pyridoxine-doxylamine, antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine, meclizine), phenothiazines (e.g. promethazine), and ondansetron, when used appropriately.

Beyond pharmacological management, dietary and lifestyle modifications play a significant role in alleviating symptoms. Encouraging patients to consume small, frequent meals with an emphasis on protein rather than fats and carbohydrates while avoiding strong odors, greasy foods, and overly sweet items can help reduce nausea [24, 25]. Proper hydration strategies should also be emphasized, including separating liquid intake from solid meals to minimize gastrointestinal discomfort [26]. For women requiring intravenous hydration, normal saline (0.9% NaCl) with added potassium chloride is recommended, with administration guided by daily electrolyte monitoring. In cases where a single antiemetic is ineffective, a combination of agents should be considered.

Before considering termination of pregnancy, all possible therapeutic measures should be explored to ensure optimal management of severe NVP and HG. This includes the use of corticosteroids in treatment-resistant cases, as recommended by clinical guidelines, given their potential efficacy when other options have failed.

Early recognition and timely intervention in Hyperemesis Gravidarum (HG) are crucial for preventing weight loss, general weakness, and recurrent hospitalizations. Comprehensive treatment should include medical management, patient education, dietary and lifestyle modifications, and emotional support. Such an approach not only improves maternal health and quality of life during pregnancy but also reduces the need for parenteral therapy, alleviating both the financial and emotional burden on families and the healthcare system [4, 10, 21].

There is limited evidence suggesting that pregnant women with HG often found interactions with healthcare professionals challenging, with many reporting that their concerns were dismissed and that the complications of HG were downplayed [27]. In response to these challenges, Irish researchers have strongly advocated for the establishment of dedicated HG clinics. This type of service is an example of both individualized and multidisciplinary care. These interdisciplinary services offer comprehensive care, treatment, and support from midwives, dietitians, obstetricians, and mental health specialists. Patients attending these clinics receive an individualized assessment from a dietitian at each visit, with specialists determining the necessity of intravenous (IV) fluid therapy and vitamin supplementation, as well as reviewing or adjusting medication doses. As concluded in the study, dedicated multi-disciplinary HG clinics, available nationally and internationally for all women with HG, are strongly recommended [28].

Severe HG when left unmanaged, can progress to serious complications, including WE, necessitating a coordinated, interdisciplinary approach to patient care. This collaboration involves obstetricians, midwives, neurologists, psychiatrists, addiction specialists, dietitians, and social workers, each contributing their expertise to address the multifaceted needs of affected patients [29].

Midwives and obstetricians are often the first to detect signs of excessive vomiting and associated nutritional deficiencies during pregnancy. Their role includes monitoring for symptoms such as severe dehydration, weight loss, and neurological changes that could indicate the development of WE. Educating healthcare providers on the early neurological signs of thiamine deficiency, beyond the classical triad of WE, is essential to prevent delayed diagnosis. Early referral to neurologists is essential for assessing and managing potential cognitive or motor impairments resulting from thiamine deficiency that are a hallmark of WE [21, 23, 30].

In cases where hyperemesis may be linked to alcohol misuse, psychiatrists and addiction specialists are vital for evaluating and treating underlying dependency issues [30,31,32]. Comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety and depression, are common in HG and require integrated mental health support. This includes addressing the psychosocial challenges that may exacerbate the condition, such as stress, anxiety, or inadequate social support. Dietitians play a crucial role in monitoring and addressing nutritional deficits, ensuring adequate thiamine supplementation, and providing dietary strategies to minimize symptoms of HG [33, 34].

Social workers complete the interdisciplinary framework by assessing the patient’s broader circumstances, including access to food, housing stability, and overall well-being. They can facilitate interventions when social determinants of health, such as financial hardship or unsafe living conditions, hinder recovery.

Our case highlights the importance of early identification and treatment of thiamine deficiency in pregnant patients with hyperemesis gravidarum to prevent irreversible neurological damage. Understanding the risk factors, the need for screening and early intervention, and algorithmic management of treatment is crucial. When considering the evidence from our case report alongside findings from the literature, it becomes evident that a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach not only enhances maternal outcomes but also protects fetal development. This underscores the importance of early detection, holistic care, and coordinated efforts among healthcare providers to prevent severe complications associated with thiamine deficiency [29].