by Robert Schreiber

Berlin, Germany (SPX) Nov 12, 2025

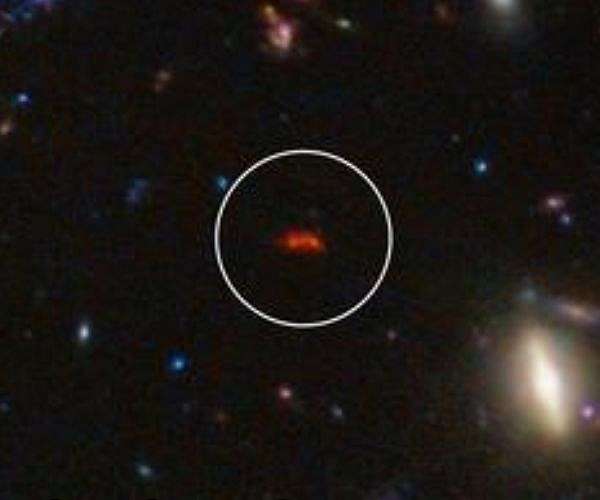

An international team of astronomers, led by Tom Bakx from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, has identified a galaxy forming stars at a pace 180 times faster than…

by Robert Schreiber

Berlin, Germany (SPX) Nov 12, 2025

An international team of astronomers, led by Tom Bakx from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, has identified a galaxy forming stars at a pace 180 times faster than…