Introduction

The vaginal pessary is a commonly used intervention for management of pelvic organ prolapse, ideal for its safety profile and efficacy in patients even with the most severe medical comorbidities or who are otherwise poor surgical candidates. Commonly encountered adverse events related to pessary use include vaginal discharge, bleeding, and superficial mucosal erosion. However, more severe complications such as full-thickness vaginal erosion, pessary migration into the bladder, and rectovaginal and vesicovaginal fistula not only present with significant comorbidity for patients but also pose significant challenges for surgeons when attempting to repair such defects. Cases of staged transvaginal or open fistula repair due to Gellhorn pessary erosion into the bladder have been reported.3-5 We present a rare case of ring pessary erosion resulting in complete bladder rupture with eversion and grade 4 prolapse of bladder, ureters, cervix, and small bowel through the vaginal vault repaired in a single stage entirely via transvaginal approach.

Case Presentation

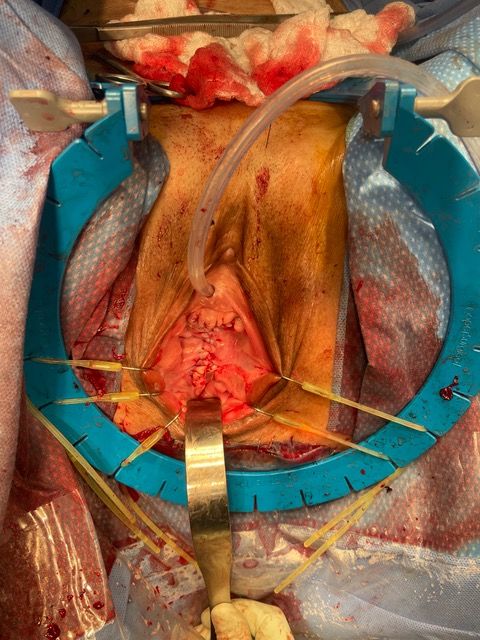

A 73-year-old woman with multiple medical comorbidities, including poorly controlled eczema, 50 pack-year smoking history, and grade 4 uterine prolapse, was managed with a ring pessary in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the next 4 years, she was unreliable with follow-up, reporting a total of 3 pessary changes. After she presented to an outside emergency department with a urinary tract infection, her pessary was removed, and subsequent cystoscopy and hysteroscopy revealed erosion into the bladder and uterus. Upon presentation to our clinic, examination demonstrated grade 4 uterine, bladder, and vaginal vault prolapse with nodular edema of the vaginal wall and cervix. The bladder was ruptured, bivalved at the midline, with complete eversion and exposure of the bladder lumen and excoriated intravesical mucosa, including ureteral orifices (UOs) (Figures 1A-C). CT scan revealed a large volume of pelvic fat prolapsing below the pubococcygeal line. Pelvic congestion with poorly visualized bladder presumed to represent complete bladder, uterine, and vaginal prolapse. Pelvic ureters were severely J-hooked bilaterally with moderate dilation down to the prolapsed bladder (Figures 2A-B).

Figure 1A. Exam on presentation. Prolapsed anterior vaginal wall (A), ruptured bladder, bivalved at the midline (B), cervix (C), and nodular edematous vaginal wall (V).

Figure 1B. Exam on presentation. Posterior perspective demonstrating excoriated mucosa of the lumen of ruptured bladder (B), prolapsed cervix (C), and nodular vaginal wall (V). Note the efflux of urine visualized via the exposed and laterally displaced ureteral orifices (UO).

Figure 1C. Exam on presentation. Sagittal perspective.

A single-stage transvaginal approach was performed for complete repair of the above-mentioned findings. Bilateral ureteral stents were placed into the exposed and laterally displaced ureteral orifices prior to reduction of the bladder prolapse. An intact urethral meatus and bladder neck were identified, although distorted, within the edematous anterior vaginal wall above the cystotomy. The large bladder defect was mobilized, leaving a 5-mm perimeter of vaginal epithelium for closure, beginning anteriorly sparing the urethra and bladder neck, moving posteriorly around the defect until a large enterocele and bilateral stented ureters were encountered. A LigaSure was used to excise the nodular vaginal mucosa adherent to the bladder base and enterocele, at which point the uterine fundus became visible with notably elongated vascular pedicles and pelvic ligaments. At this point, the bladder was reduced, a transvaginal hysterectomy was performed, and the remaining large vaginal wall nodules were excised. All specimens were sent for pathology. The enterocele sac was dissected off to allow debridement of the remaining vaginal wall. The enterocele sac was closed with a 2-0 Monocryl purse string suture. The posterior vaginal wall was closed in 2 layers, first with a 0 polydioxanone (PDS) interrupted layer, followed by closure of the vaginal epithelium with a 2-0 polyglactin (Vicryl) running suture.

Figure 2A. Sagittal view of CT. Large volume of pelvic fat prolapsing below the pubococcygeal line. Complete prolapse of ruptured bladder, uterus, and vaginal vault.

Figure 2B. Coronal view of CT. Prolapse of ruptured bladder and pelvic ureters. Bilaterally J-hooking with moderate pelvic hydroureter.

At this point, the bladder was addressed, now assuming a fairly normal shape, with UOs and stents visualized away from the large defect. The bladder was closed in a T shape for the least amount of tension. Full-thickness interrupted 2-0 Monocryl sutures were used to reapproximate the bladder edges, incorporating the 5-mm rim of vaginal epithelium for added strength. The bladder base was then reconstructed with a series of running and interrupted full-thickness 2-0 Monocryl sutures to ensure a watertight closure.A 22-French 2-way silicone Foley catheter was placed, and a leak test was performed, at which point 2 areas were oversewn using 3-0 Monocryl. Additional anterior vaginal wall was resected to facilitate final closure. Anteriorly, the vaginal epithelium was closed in similar layers of interrupted deep 0 PDS and superficial running 2-0 Vicryl (Figure 3A-B). A Kerlix gauze was used for a vaginal pack and secured in place by sewing the labia closed with a single 0 silk stitch.

Figure 3A-B. Following final vaginal closure.

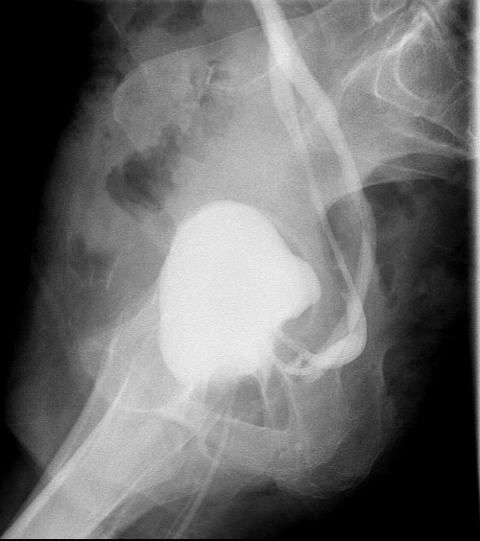

The patient was admitted overnight for observation. The silk stitch and vaginal pack were removed, and she was discharged without complications on postoperative day 1. A cystogram was performed at 3 weeks postoperatively, which demonstrated normal bladder contour without extravasation of contrast (Figures 4A-B). A cystoscopy with bilateral ureteral stent removal was performed in clinic the same day.

Figure 4A. Anteroposterior view of cystogram at 3 weeks postoperative. Normal bladder contour without extravasation of contrast. Bilateral ureteral reflux as expected with stents in place.

Figure 4B. Sagittal view of cystogram at 3 weeks postoperative. Chronic J-hooking of ureters visualized with stents in place.

Discussion

Pessaries are a safe and effective form of nonsurgical management for pelvic organ prolapse. However, neglected pessaries can result in severe complications.4Minor complications related to pessary use such as vaginal discharge, bleeding, and superficial mucosal erosion are reported at rates as high as 83% of women using a pessary for greater than 1 year.2 There are, however, exceedingly rare reports of severe adverse complications.1 Gellhorn and donut pessaries are known to be more commonly associated with worse complications, including full-thickness erosion and vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula, than ring-type pessaries.2 Although the majority of pessary complications can be managed conservatively with removal of pessary, vaginal rest, and initiation of vaginal estrogen, more severe adverse events will require surgical intervention.

There is limited information in the literature to guide the management of fistulae and prolapse repair related to pessary erosion.4Staged repair, either open or transvaginal, is currently the mainstay of treatment. Single-stage transvaginal repair appears to be much less common, especially in the case of such severe presentation, as with our patient. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of complete eversion and prolapse of ruptured bladder with associated grade 4 prolapse of uterus and cervix, ureters, and small bowel secondary to ring pessary erosion with successful single-stage repair entirely via transvaginal approach.

Conclusion

Major complications of ring pessaries are rare but present considerable challenges to surgeons and patients when they do occur. We present favorable outcomes associated with a severe ring pessary erosion and bladder rupture using a single-stage transvaginal approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This research did not receive any specific grant or funding from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

1. Dabic S, Sze C, Sansone S, Chughati B. Rare complications of pessary use: a systematic review of case reports. BJUI Compass. 2022;3(6):415-423. doi:10.1002/bco2.174

2. Kakkar A, Reuveni-Salzman A, Bentaleb J, Belzile E, Merovitz L, Larouche M. Adverse events associated with pessary use over one year among women attending a pessary care clinic. Int Urogynecol J. 2023;34(8):1765-1770. doi:10.1007/s00192-023-05462-z

3. Lewis GK, Leon MG, Chen AH. Erosion of a Gellhorn pessary into the bladder: a report of transvaginal removal and repair of vesicovaginal fistula. Int Urogynecol J. 2023;34(1):309-311. doi:10.1007/s00192-022-05352-w

4. Mathews S, Laks S, LaFollette C, Montoya TI, Maldonado PA. Staged repair of concomitant rectovaginal fistula and pelvic organ prolapse after removal of a neglected pessary. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33(4):686-688. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1792818

5. Yan S, Walker R, Sultan AH. Open removal of a migrated Gellhorn pessary and repair of a vesicovaginal fistula. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(7):e233986. doi:10.1136/bcr-2019-233986