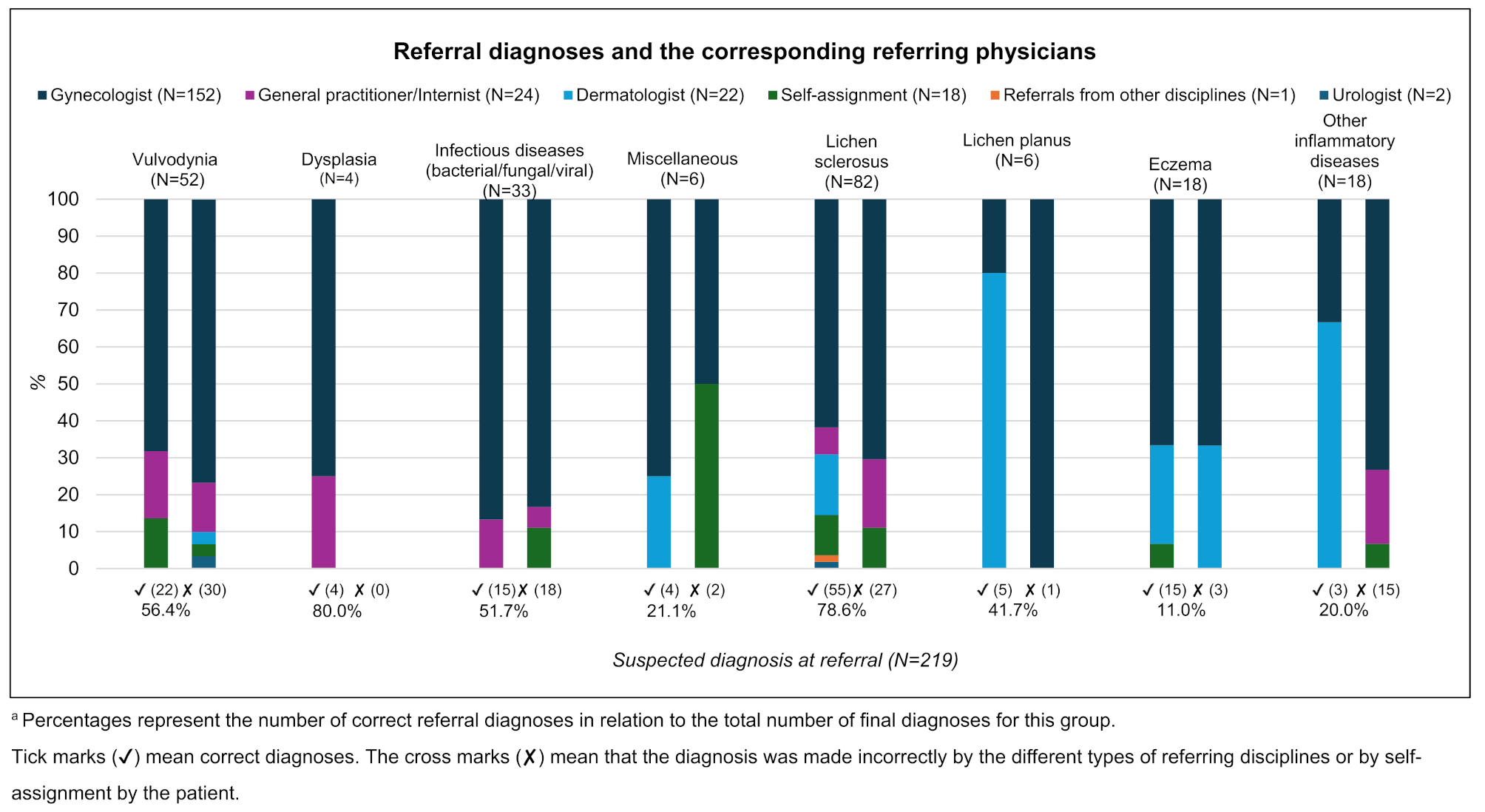

Although most referrals to the specialized vulva clinic were made by specialists, little more than half of the suggested diagnoses could be confirmed, which is in line with other results and represents a major potential for improvement in diagnostic approaches [8, 12]. While the overall correctness of suggested diagnosis was disappointingly low, there were marked differences among specific vulvar disorders and the clinical background of referring specialists. Significant inconsistencies in vulvar diagnosis were also found between referring physicians and dermatologists in a recent study [13]. The higher diagnostic accuracy observed in dermatologists may be attributable to the referral bias where mainly complex or refractory cases are referred and not the straightforward vulvar cases. A referral bias is also reflected by the difference referrals with a diagnosis or a suspected diagnosis (68.5% from gynecologists vs. 91.7% from dermatologists). Further, most vulvar pathologies are dermatoses, which are familiar to dermatologists as they also appear on other areas of the body. Dermatologists typically conduct a full body examination, including the oral cavity, and at least inquire about any genital involvement. Many dermatoses, such as eczema or psoriasis, can affect the vulva, but they are usually not limited to the genitalia, which generally provides the dermatologist with a clue for the diagnosis. In contrast, gynecologists have significantly less exposure to vulvar and gynecologic dermatology, as vulvar diseases are addressed only at a limited number of specialized centres in Switzerland.

There is a potential referral bias: dermatologists might be confident with their dermatological diagnoses but not with the exclusion of an underlying gynecological disease, whereas gynecologists are confident with their exclusion of a genital pathology but not so with their dermatological diagnoses. The learning objectives of the Swiss OB/GYN specialty program include the detection, prevention and treatment as well as the follow-up of diseases of the female genital organs, however there is no specific emphasis in vulvar dermatology. The inclusion of learning objectives in vulvar dermatology should be implemented in the National OB/GYN specialty programs (Fig. 2).

Challenges and tools for efficient and reliable diagnosis of vulva diseases

For lichen sclerosus the concordance between referral and final diagnosis was high, which is likely due to the characteristic clinical signs of this disease [14] and supports the claim that both clinical expertise and experience in vulvar disorders play an important role in diagnostic outcome. However, in line with further results [8, 14,15,16,17,18], the frequent fear of dysplasia/vulvar cancer in suspected lichen sclerosus cases, likely motivated referral for re-evaluation in a tertiary center. In addition, reluctance to use strong topical steroids for a prolonged period is a well-known reason to refer women with lichen to a specialist clinic [8, 19, 20]. The suspicion of dysplasia, eczema, and lichen planus also proved to be most often correct, which should probably be attributed to their clear diagnosis, either by biopsy or by specific characteristics of clinical presentation [14]. However, eczema had relatively often been mistaken for lichen sclerosus, which was the most frequently corrected diagnosis through histopathological evaluation of biopsies. The great variety of other inflammatory diseases and subtle differences in their classification probably explain the considerable difference between suspected and final diagnoses in this group [2, 9, 21]. Although these diseases are commonly seen in gynecologists’, dermatologists’, and general practitioners’ daily clinical routines [10, 18, 22, 23], infectious diseases were often falsely diagnosed, which is likely also a consequence of the broad spectrum of clinical symptoms [1, 14, 24, 25]. Vulvodynia is an exclusion diagnosis, i.e. all relevant diagnostic tests have to be completed before the final diagnosis can be made [26, 27]; this was often not the case before the patient was referred. Unspecific symptom descriptions likely also contributed to the underestimation of this diagnosis [26,27,28].

With only 44% of patients reporting similar key symptoms when they saw a referral physician as at the first consultation in the specialized center, the agreement between symptoms on the two occasions was relatively vague. Although some of the discrepancy may be a result of reporting bias, symptoms or their intensity may also have changed and consequently have been reported differently at the two appointments. In addition, physicians will likely have explored symptoms in many ways, ranging from no direct question on symptoms at all to a highly complex exploration via a predefined symptom list. A guideline as to what and how information on symptoms should be collected might help to improve diagnostic quality [10, 12, 29].

While it took a long time after onset of symptoms for patients to be referred to the specialized vulva clinic, the tests needed to permit final diagnosis were completed rather quickly. The mean time between symptom onset and final diagnosis in our study was 46.1 months, with 1.0 month from the 1st consultation in the vulva clinic until final diagnosis, which is in line with other findings [18].

Differences in the time to diagnosis might be due to a deliberate, partial investigation of vulvar disease prior to referral, with the final diagnosis—especially when more sophisticated approaches such as vulvar colposcopy, dermoscopy, or biopsies are needed—being left to the specialized vulva clinic [8, 9, 29]. However, if gynecologists consider themselves to be specialists supporting women with vulvar complaints, it would be beneficial to improve their expertise to allow more reliable diagnoses or early pre-defined referral to a center offering the diagnostics tools and experience needed. The high number of vulva disorders that are a manifestation of a skin disease accords with their frequent correct initial diagnosis by referring dermatologists [18].

One reason for the limited diagnostic quality of the initial evaluation of vulvar diseases might be based on the variety, how different diagnostic tests are used in clinical practice. While bacterial/mycosal smears were frequently made, biopsies were only rarely taken, and no patterns could be detected in the performance of such biopsies among referring physicians. While some physicians, tended to steer the diagnostic process to a clear diagnosis, others referred women at some point of the diagnostic process to the tertiary vulva care center. Here, either a clear definition of how tertiary centers could ideally cooperate with primary caregivers, or better training in when, how and where biopsies should be taken would be helpful in improving diagnostic success in vulvar diseases.

In line with this finding, the cotton swab test, which, in addition to excluding other causes of vulvar pain [2, 26, 30], is mandatory for the diagnosis of vulvodynia, was only carried out in about 15.4% of women before they were referred to the tertiary center. As vulvodynia is among the most frequent vulvar disorders [31] the systematic realization of this test would help to increase diagnostic accuracy in a large proportion of vulvar diseases. As vulvar pain can also be a comorbidity of other vulvar diseases [26, 32, 33], it is important to exclude any other pain-inducing disease.

In agreement with the literature, the almost 4 years’ latency from symptoms to referral was seen more often in diseases with a fluctuating character, such as eczema and lichen sclerosus [14]. A delayed diagnosis of a dermatoses can lead to significant physical, psychological, and medical complications, depending on the specific condition. A long delay often of several years in diagnosing lichen sclerosus and lichen planus can result in progressive scarring, atrophy, and adhesions, which may lead to functional impairment and distress (e.g., narrowing of the vaginal or urethral opening) as well as an increased risk of the development of squamous cell carcinoma [34]. Furthermore, misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary treatments, potentially worsening the patient’s condition or causing irreversible changes to the vulva appearance.

Latency was also high in diseases such as vulvodynia and other inflammatory diseases. Time from initial symptoms to final diagnosis was shortest for infectious diseases, which might be a result of sudden strong clinical symptoms, which motivated both patients and physicians towards an early solution. In contrast, the time from the onset of the first symptoms to the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus was the longest in our cohort, averaging nearly 7 years, which is longer than the 4 years reported in a survey study by Krapf et al., where women indicated they received the correct diagnosis after this duration [35].

In 225 women a diagnosis could already be formulated at the first consultation by confirming or rejecting the suspected diagnosis of a referring doctor, with 90.4% of the women receiving a final diagnosis after a maximum of two consultations. These data show that when the right approach is chosen, most vulvar diagnoses can be made very straightforwardly. While physicians can only influence patients to seek medical support to a rather limited extent, they can use this resource to facilitate earlier diagnosis and, consequently, earlier treatment.

The most common pitfalls in the diagnosis of vulvar diseases and solutions for overcoming challenges to correct diagnosis are summarized in Fig. 2 [1, 14, 28, 36]. To guarantee best diagnostic quality, if histopathological evaluation is required it should be performed by a dermato-histopathologist with experience in vulvar pathology [37]. Specific immunohistochemical markers for neuroproliferative vestibulodynia might offer future options in the classification and patho-etiology of vulvar pain [38]. Specialists supporting women who have vulvar diseases should also follow well-defined approaches to treating vulvar disorders, for example, approaches to managing vulvovaginal symptoms [29] or vulvar disorders [14]. For a standardized diagnostic method, health professionals should adhere to existing diagnostic protocols, such as the European Guideline for the Management of Vulval Conditions [14].

Shame and hesitancy to seek medical support, possibly also due to cultural background are factors hampering timely diagnosis on the patient’s side [39]. Active investigations of vulvar complaints in an atmosphere facilitating discussion of delicate topics should therefore be a standard component of taking a gynecological history [12]. Specific attention has to be paid to multiple conditions.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are the large study group and the inclusion of study participants over a period of 4 years in a real-life setting. Limitations include the retrospective data collection based on a type of documentation that was not expressly designed for the present evaluation. Despite the presence of multiple symptoms, only the leading symptom was used to compare the initial situation and the situation in the tertiary center. The intensity of several important symptoms might have changed over time and consequently have resulted in an overestimation of discrepancies. Although there was no systematic internal quality assessment of the diagnosis, we considered final diagnoses from the tertiary center to be correct. As referring physicians individually decided which information should be included in the referral letter, individual effort invested in the correctness and completeness of reports might have varied strongly and not all details of investigations occurring before referral might have been brought to the attention of the tertiary center. Another limitation is the comparison of correct diagnoses of gynecologists compared to dermatologists as the vast majority, nearly 70%, of the referrals were from gynecologists and only 7.4% from dermatologists.

However, this first systematic evaluation of suspected diagnoses before patients were referred to a tertiary hospital vulva clinic and later outcomes of additional diagnostic steps provides valuable targets for the improvement of diagnoses in primary health support.