Study population

The study included two population-based prospective cohorts: the Cohort of Swedish Men (COSM) and the Swedish Mammography Cohort (SMC). The COSM was established in 1997 when all men born in 1918–1952 residing in central Swedish counties (Västmanland and Örebro) were invited to join the cohort. The SMC was established in 1987–1990 when all women born in 1914–1949, who lived in Västmanland and Uppsala counties, were invited to a mammography-screening program.

In late fall 1997, 48,850 men (49% response rate) and 39,227 women (70% response rate) completed a 96-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and answered questions about lifestyle factors (the questionnaires are available: https://www.simpler4health.se/researchers/questionnaires/).

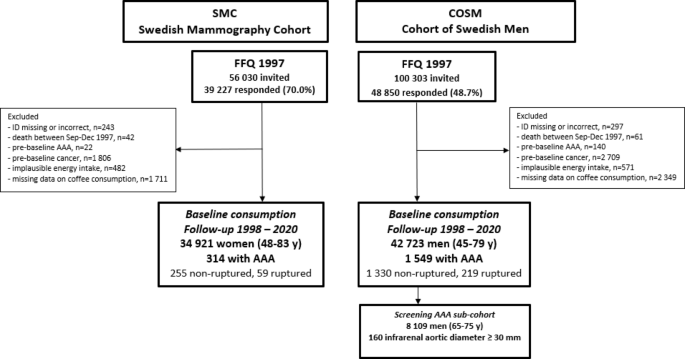

Of the 48,850 men and 39,227 women who completed the questionnaire in 1997, we excluded participants with an incorrect or missing personal identity number, participants who died before the start of follow-up (January 1, 1998), and those with pre-baseline AAA diagnosis – Fig. 1. Moreover, due to the tendency to adopt healthier lifestyle behaviors after a cancer diagnosis (including dietary changes) and the simultaneous presence of an increased risk of death and cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence, participants with a pre-baseline diagnosis of cancers other than non-melanoma skin cancer were excluded. Additionally, participants with implausible energy intake (± 3 SDs from the mean value of the loge-transformed) and those with missing data about coffee consumption were also excluded. After these exclusions, 42,723 men and 34,921 women were left for analysis.

Participants were followed from baseline (January 1, 1998), to the date of diagnosis of AAA or AAA repair, death, or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2020), whichever occurred first.

Flow-chart of the Swedish Mammography Cohort (SMC) and the Cohort of Swedish Men (COSM). Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire.

Assessment of coffee consumption and covariates

The validated 96-item FFQ was used to collect data on coffee and other foods consumption in 19977. Using an open-ended question, participants were asked how often daily, on average, during the last year, they consumed coffee, tea, and how many spoons of sugar they used. Based on one-week weighted diet records, a cup of coffee was defined from 160 to 210 ml (depending on the age and gender of participants). Energy intake was calculated by multiplying the frequency of food consumption by age-specific and gender-specific portion sizes and by the energy content of each food item8. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet was assessed using a previously developed modified Mediterranean diet (mMED) score9,10. The mMED score ranged from 0 to 8 points, and 0 points meaning the lowest adherence to the Mediterranean diet, while 8 points the highest adherence. In a validation study including 129 women from the SMC, comparing the FFQ to four one-week weighted diet records the Spearman correlation coefficient for coffee consumption was 0.63 [Wolk A, unpublished data].

Information about education level, body height and weight, time spent on walking and/or cycling, aspirin use, history of hypercholesterolemia, and family history of myocardial infarction (< 60 years old) was collected using the questionnaire. Participants were also asked about smoking status, age when they started smoking, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day through specified age categories (15–20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–60 years old and in current age), and if applicable about age of quit. Pack-years of smoking were calculated by multiplying the number of years of smoking by the reported number of cigarettes smoked per day within specific age categories. Data about history of diabetes was collected through linkage of participants’ ID with the National Diabetes Register and with the National Patient Register (ICD-10: E10-E14). Data about pre-baseline cardiovascular diseases (CVD) included cases of ischaemic heart disease (ICD-10: I20-I25), heart failure (I50, I110), stroke (I60, I61, I63, I64), and atrial fibrillation (I48) was collected via linkage with the National Patient Register. Data about history of hypertension was collected through linkage with the National Patient Register (I109) and complemented with self-reported data.

Ascertainment of AAA

Incident cases of AAA, AAA repair, and death due to AAA were identified via linkage of the participants with the Swedish Inpatient Register and the Swedish National Cause of Death Register. We used the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems − 10th Revision (ICD-10) to identify non-ruptured and ruptured aneurysm in the abdominal aorta (I71.4 and I71.3, respectively). AAA repair was identified through the Swedish Inpatient Register by use of the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures, and the Swedish National Registry for Vascular Surgery (Swedvasc) by use of the integrated AAA module in that registry. The Swedish Inpatient Register has no specific validity assessment for AAA; however, in general it has a high validity11 and nearly complete hospitalization data for the Swedish population since 198712,13. Surgical procedures have been reported as incorrect in 2%, and missing in 5.3% of the records11and in an independent international validation, the external validity was 98.8% for AAA repair13.

AAA screening sub-cohort

An analysis of a sub-cohort of 8109 men from the COSM who were screened for AAA during follow-up as a part of the national screening program (65–75 years old), using an infrarenal aortic diameter (IAD) ≥ 30 mm as outcome14,15 was performed.

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of total AAA and separately of non-ruptured and ruptured AAA. Coffee consumption was categorized as follows: ≤ 1.0 (reference), 1.1-3.0, 3.1-5.0, or > 5.0 cups/day. Model 1 was adjusted for age at the study baseline, sex, education, pack-years of smoking, and smoking cessation. Model 2 included the adjustments in Model 1, with additional adjustments for walking/cycling, BMI, aspirin use, history of diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, CVD, family history of myocardial infarction, and tea consumption, sugar consumption, energy intake, and mMED score. To keep all participants in analyses missing data on educational level (0.5%), smoking status (5.4%), walking/cycling (8.7%), BMI (3.6%) and aspirin use (10.7%) were included in the models as separate categories. All covariates were prespecified and included in the models because they are known risk factors of AAA or potentially related to AAA and coffee consumption.

We have tested the assumption of proportional hazard using regression scaled Schoenfeld residuals against survival time, and no evidence of departure from the assumption was found. Using a likelihood ratio test, the interactions on the multiplicative scale between categories of coffee consumption and sex and smoking status were tested. Moreover, relative risks due to interaction (RERI) and attributable proportion of interaction (AP) were used to assess the additive interaction. Using a restricted cubic spline regression analysis with three knots (at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles), the shape of associations between coffee consumption and risk of non-ruptured and ruptured AAA was examined. Linear trends were estimated by including daily cups of coffee consumption in the models as a continuous variable. Moreover, absolute risk difference (ARD), number needed to harm (NNH), and population attributable fraction (PAF) were calculated to further quantify the impact of coffee consumption on AAA. Additionally, we conducted mediation analyses using med4way Stata command to investigate the direct effect of coffee consumption on total AAA and the indirect effect mediated by smoking16,17.

An association between coffee consumption and IAD (< 30, ≥ 30 mm) was assessed using a multivariable logistic regression model in the screening sub-cohort of the COSM. The multivariable odds ratios (ORs) were adjusted for the same confounders as the Cox proportional hazard models except for the age, where age at screening instead of this at the study baseline was included.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software, version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Reported P-values are two-sided and the values ≤ 0.05 were generally considered statistically significant. To account for multiple tests, Bonferroni correction was applied for P-values.