Samsung’s Galaxy S26 Ultra won’t have many upgrades compared to its predecessor, but one of the rumored ones is the ability to make its screen invisible to anyone but you, the owner. And now this feature has actually been confirmed by One…

Author: admin

-

Wellness or Woo-Woo? The Trending Experiences Everyone’s Trying

Some experiences promise deep relaxation, others a spiritual jolt, and many are just delightfully woo-woo. From crystal-lined therapy rooms and cacao ceremonies, the modern wellness world, now valued at around $1 trillion and…

Continue Reading

-

The electric vehicle transition and vanishing fuel tax revenues

The world is rapidly transitioning to battery-electric vehicles (BEVs), with internal combustion engine (ICE) sales declining1. Consequently, public revenues from motor fuel taxes are falling, creating potential fiscal gaps if not replaced2. This trend has been unfolding for years due to ICE efficiency gains and the rise of hybrid vehicles, but now the transition to full BEVs amplifies the effect, and several countries already face fiscal pressures (Supplementary Table 1). While prior studies have assessed this dynamic in advanced3,4,5 and some middle-income economies6, its implications for low- and lower-middle-income countries remain underexplored7. Critics may argue that expanding electricity access should take priority in such contexts; however, the BEV transition is accelerating faster than expected8. Cost declines and design improvements, largely driven by Chinese automakers and battery manufacturers, have brought affordable BEVs to global markets9,10. China’s BEV sales are projected to surpass ICE sales in 202511, and tariffs on Chinese vehicles in the USA and Europe are pushing low-cost BEVs into developing markets. This shift is already visible across Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa, where imports from BYD, Leapmotor and JAC Motors are rising12. This situation raises three key questions: how large is the fiscal impact of declining fuel tax revenues, how does it vary across countries and what policy options exist to address it?

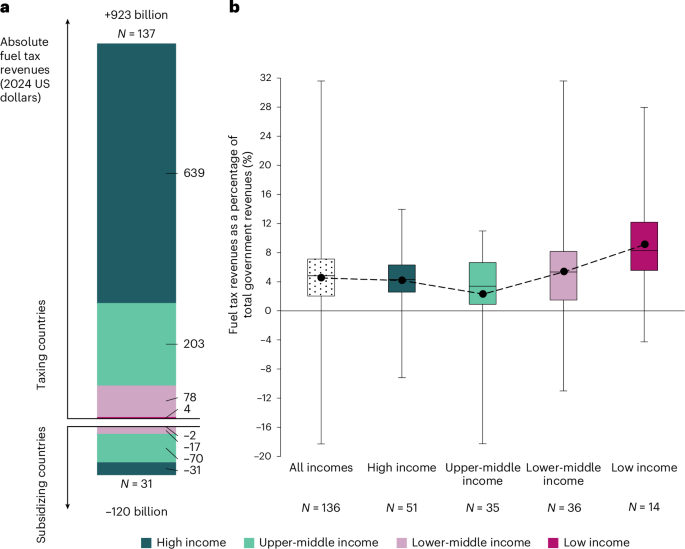

To address these questions and bring evidence to the policy discourse, we assembled a new dataset of global fuel tax revenues from gasoline and diesel road vehicles by collecting data from multiple sources and performing some simple transmutations following the benchmark gap approach (Methods). This price gap approach compares local retail prices to a global benchmark price—typically international spot prices for motor fuels—where the difference reflects the presence of a tax or subsidy. While this method has important limitations, including the assumption of uniform benchmark prices and distribution costs across countries as well as consistent retail and marketing margins within countries, it remains a highly relevant and practical tool for quantifying and comparing fuel price distortions across a wide range of national contexts. The data cover 168 countries across four income levels, with the most recent year of data availability being 2023. They include tax revenues from both motor gasoline and diesel. While we recognize that a substantial portion of diesel is consumed by heavy-duty vehicles—whose electrification is progressing more slowly—this fuel remains a key component of overall road transport taxation in many countries13. We found that 137 countries implement a net tax on road vehicle fuel, whereas 31 countries provide net subsidies to road vehicle fuel (Fig. 1a). In total, we estimated that over US$920 billion (in 2024 US dollars) were collected in fuel tax revenues across the 137 taxing countries in 2023. To put this figure into comparison, in 2023 the global investment into renewable power generation was reported at US$735 billion14.

Fig. 1: Global motor fuel tax transition exposure in absolute terms and relative terms as a percentage of total government revenues. a, Fuel tax revenues are shown for taxing countries on the positive y axis (N = 137 countries) and subsidizing countries on the negative y axis (N = 31 countries). Values are calculated for the year 2023 and shown in real 2024 US dollars. Country income levels are grouped according to the World Bank classification. The definition of taxing versus subsidizing countries follows the benchmark gap approach detailed in Methods. The labels for +US$4 and –US$2 billion point to the low-income taxing and subsidizing countries, respectively, in bright pink. b, Fuel tax revenues as a percentage of total government revenues for all countries (N = 136), high-income countries (N = 51), upper-middle-income countries (N = 35), lower-middle-income countries (N = 36) and low-income countries (N = 14) for the year 2023. The lower and upper box boundaries represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The line inside the box represents the median, and the lower and upper whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum of all the data, respectively. The black dots connected by the dashed black line represent the average within each country grouping. Note that the total number of countries in b is lower due to data availability constraints (see Methods for further explanation). See Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, which display a sensitivity analysis of this figure with high and low benchmark assumptions (Los Angeles CARBOB and Singapore Mogas 92 RON, respectively) for refined gasoline and diesel. See also Supplementary Fig. 3, which reproduces this figure with four outlier countries (Benin, Jordan, Yemen and Venezuela) adjusted.

Source data

Beyond absolute exposure, we found that relative fuel tax revenue exposure varies greatly across countries. As a percentage of total government revenues, fuel tax revenues in most countries fall between 4% and 8%. However, when comparing relative exposure by income level, we found that low-income countries are the most affected, with over 9% average exposure, whereas upper-middle- and high-income countries face considerably lower levels, around 2–4% on average. This means that low-income countries face about three times the exposure to potential revenue loss from declining fuel taxes compared with their more affluent counterparts. For context, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries spend on average 15% of total government revenues on education, 26.5% on health and 6.5% on defence15,16.

The decarbonization of the economy has led and will be leading to changing sources of public revenues. High- to middle-income countries have begun tapping new sources of revenue, such as carbon taxes or road tolls. High-income countries can do this with a relative ease of implementation—that is, their high administrative capacity and broad-based fiscal frameworks allow for swift adjustment to recover lost revenues. Low-income countries may not be as well equipped, lacking the institutional quality or organizational structure required to design new tax schemes. In the case of the transition to BEVs, most low- to lower-middle-income countries with high percentages of total government revenues generated by fuel tax also exhibit weak institutional quality (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Country-specific fuel tax transition exposure versus institutional quality.

Fuel tax revenue exposure, on the y axis, is calculated as motor fuel tax revenues as a percentage of total government revenues for the year 2023. Institutional quality, on the x axis, is assessed per country on the basis of the World Governance Indicators from the World Bank Group for the year 2023. See Supplementary Note 1 for a full description of how each axis is calculated. The countries are colour-coded to indicate income level according to the World Bank classification. High-, upper-middle-, lower-middle- and low-income countries are shown in dark green, light green, light pink and dark pink, respectively. The countries are shape-coded to indicate the presence of a debt crisis according to data from the Justice Debt Portal. Countries in a debt crisis are depicted with triangles and countries not in a debt crisis with shaded circles. The 19 countries where debt crisis data are missing are depicted with hollowed circles. We found a negative correlation (Pearson coefficient r = −0.27 for 115 taxing countries) between fuel tax transition exposure and institutional quality. See Supplementary Fig. 4, which reproduces this figure with four outlier countries (Benin, Jordan, Yemen and Venezuela) adjusted.

Source data

In addition, many exposed countries are in a debt crisis, leading to a greater risk of exposure. In the aftermath of COVID-19, debt distress surged in low- and middle-income countries as governments increased borrowing to offset deficits caused by reduced economic activity and rising public health-care expenditures during lockdown17. This was further exacerbated by limited access to global financial markets and currency depreciation. Consequently, some countries in the upper-left quadrant of Fig. 2—namely, Yemen, Benin, Lebanon, Mozambique, Madagascar, Kenya and Suriname—now face a double exposure with limited headroom to react: fuel tax revenues represent a large share of government income, institutional capacity is too weak to compensate for potential revenue losses and excessive external debt burdens make revenue compensation via debt impossible. We also note that some countries, such as Nigeria, Angola and Vietnam, are major fossil fuel producers and have invested heavily in their domestic oil and gas industries. However, with the decline in oil demand for transport due to the rise of BEVs, these investments could soon become obsolete, resulting in further revenue losses. This situation requires careful consideration, as the political economy of these vested interests may complicate the transition, thus warranting a more in-depth analysis.

In this unfolding narrative, challenges are distributed unevenly. Countries with a heavy reliance on fuel tax revenues and low institutional capacity face the greatest challenges. Should the global BEV transition continue to unfold faster than anticipated, the international community may need to offer assistance for countries with this double exposure. Institutions such as the World Bank or the United Nations Development Program could take the lead in this regard, structuring new tax implementation strategies and frameworks for road vehicles, though they should be cognizant of trade-offs. Key factors include understanding how different taxation types can support or hinder the BEV transition, offer flexibility to manage negative externalities efficiently, reduce implementation barriers and prioritize fairness more readily2. Historically, low-income countries have often relied on indirect taxes (for example, import taxes) due to easier administration18. Applying these to imported BEVs would raise upfront costs and slow adoption in high-risk markets9. Alternatives such as distance-based road charges are emerging19,20, though implementing and enforcing such systems requires substantial technical capacity. Electricity taxation faces considerable implementation barriers—particularly in informal or off-grid contexts—making it an ineffective substitute for fuel taxes or road-use revenue recovery.

When implementing tax reform, it is crucial for these international organizations to collaborate with local governments to simultaneously minimize social backlash from blanket tax hikes and manage political pushback from lost revenues. Importantly, there may be an additional dynamic that exacerbates the need for international support. In view of the increasing BEV production in China and the previously discussed import hurdles in high-income countries, lower-income countries may soon face an incoming flood of cheap Chinese BEVs. This dynamic could support both the global transition to low-carbon transport and the provision of affordable mobility for the population; however, concerns over public revenue may create incentives for governments to impose trade restrictions. Mediating this situation will be easier if policymakers are prepared with taxation options at their disposal. Interestingly, complex regulations and entrenched political interests may slow tax reform in high-income countries, whereas low-income countries, lacking institutional path dependency, could move faster if supported internationally.

As with policymaking, our analysis must be interpreted in local contexts. Applying a global benchmark price can overstate exposure in high-fuel-cost regions such as Japan or California and understate it in countries with lower environmental standards, such as Nigeria or Pakistan. This uncertainty is especially relevant for oil producers and refiners, where below-benchmark retail prices may not imply a straightforward subsidy but rather an opportunity cost to the government, reflecting forgone export revenues. Subsidy estimates for these countries should therefore be interpreted with caution. Nigeria illustrates the fiscal complexity of fuel dependence: it exports crude oil yet imports refined petroleum at market prices due to limited refining capacity. Consequently, revenue outcomes depend on fuel pricing policies and BEV adoption dynamics. Strategically balancing ICE and BEV use could therefore reduce costly fuel imports. These dynamics have two implications. First, our estimates of revenue gaps for countries that both produce and refine oil are probably conservative. Second, estimated fuel tax revenue gaps in crude-oil-exporting countries warrant more nuanced interpretation. Future research could therefore focus more closely on these countries.

The aim of our analysis is not to assess current fiscal risks from BEV penetration but rather to highlight potential future exposure as countries transition their fleets to become fully electric. As such, our framing for policymakers is forward-looking, recognizing that road transport electrification is underway but still requires sustained policy support. Namely, we suggest that national policymakers continue to support the transition to BEVs, accelerating its speed. Anticipating potential tax revenue challenges and developing strategies to address them will help policymakers sustain a supportive environment for BEV adoption throughout the transition. Our analysis suggests that policymakers should assess the exposure of their country using frameworks such as the one depicted in Fig. 2. If this assessment reveals transition challenges, alternative tax options—such as distance-based charging—will require administrative capacity and investment that must be built up over time. In many non-OECD countries, this may involve seeking support from international organizations as discussed above. When implementing such alternative tax options, policymakers should be wary of equity implications—for instance, those related to the affordability of mobility or privacy concerns. Finally, assessing the exposure of individual countries is difficult given the lack of comparable data, and we suggest that international organizations undertake a systematic effort to compile and publicly share regularly updated data on fuel tax revenues across countries. Better data and anticipatory analysis can help governments sustain BEV support by preparing alternative revenue sources, thereby increasing the likelihood of rapid global transport decarbonization.

Continue Reading

-

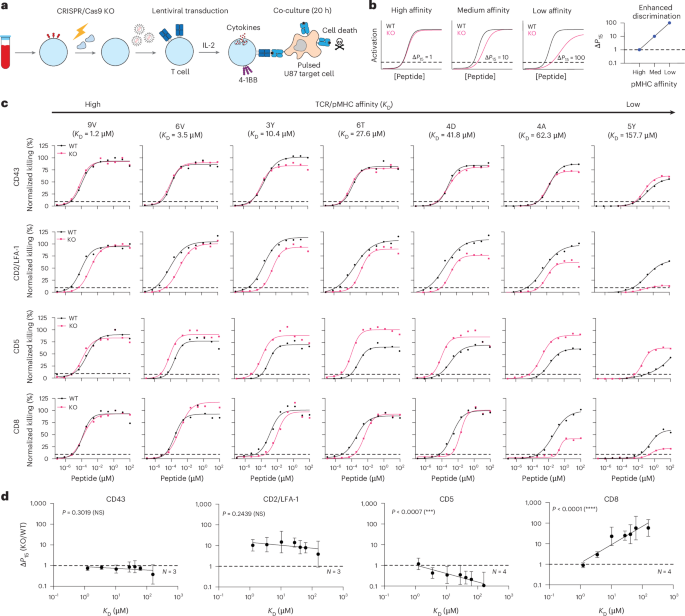

Generation of T cells with reduced off-target cross-reactivities by engineering co-signalling receptors

Cell culture

U87 and HEK cell lines were cultured at 37 ∘C and 10% CO2 in DMEM D6429 media (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 50 units ml−1 penicillin.

T2 cells and Nalm6 cells were cultured at 37 ∘C and 10% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 50 units ml−1 penicillin.

All cell lines were obtained from the ATCC except for Nalm6, which was provided by Crystal Mackall.

Primary human T cells were isolated from leucocyte cones and cultured at 37 ∘C and 10% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 50 units ml−1 penicillin and 50 U ml−1 IL-2.

Lentivirus production

HEK 293T cells (0.8 million) were seeded in a 6-well plate (Day 1) and incubated overnight. Cells in each well were co-transfected (Day 2) using X-tremeGENE HP (Roche) with 0.8 μg of the appropriate lentiviral transfer plasmid encoding an antigen receptor (1G4 TCR or c259 TCR) and the lentiviral packaging plasmids: pRSV-Rev (0.25 μg), pMDLg/pRRE (0.53 μg) and pVSV-G (0.35 μg). The media were replaced 18 h following transfection (Day 3). At 24 h after the media exchange, the supernatant from one well was collected, filtered and used for the transduction of 1 million human T cells (Day 4).

Production of TCR transduced primary human T cells

T cells were isolated from anonymized leucocyte cones (Day 3) purchased from the NHS Blood Donor Centre at the John Radcliffe Hospital (Oxford University Hospitals). Due to the anonymized nature of the cones, biological sex and gender were not variables in the present study and were therefore randomized, hence the authors were blinded to these variables. RosetteSep Human CD8+ Enrichment Cocktail (STEMCELL Technologies) was used for cytotoxic T cells, or CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail (STEMCELL Technologies) for helper T cells. The enrichment cocktail was added at 150 μl ml−1 of sample and incubated at r.t. for 20 min. The sample was diluted with an equal volume of PBS and layered on Ficoll Paque Plus (Cytiva) density gradient medium at a 0.8:1 ratio (Ficoll:sample).

The sample was centrifuged at 1,200 g for 30 min (brake off). Cells at the interface of the Ficoll media and plasma were collected (buffy coat) and washed twice (centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min). Cells were resuspended in complete RPMI media supplemented with IL-2 (50 U ml−1) at a density of 1 million cells per ml. Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (ThermoFisher) were added (1 million beads per ml) and cells were incubated overnight.

One million cells were transduced with the filtered lentiviral supernatant (Day 4). On Day 6 and on Day 8, 1 ml of medium was removed and replaced with 1 ml of fresh medium. On Day 9, Dynabeads were removed using a magnetic stand (6 days following isolation). Cells were resuspended in fresh media every other day at a density of 1 million per ml and used for co-culture experiments. At 17 days following isolation, T cells were discarded.

CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of T cell proteins

Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) were prepared by mixing 8.5 μg of TruCut Cas9 protein v2 (ThermoFisher) with 150 pmol of sgRNA mix (Truguide Synthetic gRNA, ThermoFisher) for each target gene (Supplementary Table 4) and Opti-MEM (Gibco) to a final volume of 5 μl. The RNPs were incubated for 15 min at r.t.

One million freshly isolated T cells were washed with Opti-MEM (Gibco) and resuspended at a density of 20 million per ml. The T cells were mixed with the RNPs and transferred into a BTX Cuvette Plus electroporation cuvette (2 mm gap, Harvard Bioscience). The cells were electroporated using a BTX ECM 830 Square Wave Electroporation System (Harvard Bioscience) at 300 V for 2 ms. Immediately following electroporation, the cells were transferred to complete RPMI media supplemented with IL-2, and Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (ThermoFisher) were added.

Negative selection of T cell knockout cells

T cells with residual target protein expression were depleted by antibody staining and bead pulldown. T cells were resuspended in MACS buffer (PBS, 0.5% BSA, 2 mM EDTA) at a density of 100 million cells per ml. Cells were stained with 5 μl of the corresponding PE-labelled antibody per million cells for 15 min at 4 ∘C, washed with MACS buffer and resuspended at a density of 100 million cells per ml. A volume of 1 μl of MojoSort anti-PE nanobeads (Biolegend) was added per million cells and incubated on ice for 15 min. The cells were washed with MACS buffer and the beads were pulled down magnetically. The supernatant containing the negatively selected cells was collected.

Cellular co-culture assays

U87 cells (50,000) in 100 μl of DMEM were seeded per well in a 96-well flat-bottom plate and incubated overnight. Alternatively, 100,000 T2 cells were placed in each well of a 96-well flat-bottom plate. Peptides were diluted in DMEM to the appropriate concentration, added to each well containing cells and incubated for 60 min at 37 ∘C and 10% CO2. The media were discarded and 50,000 T cells were added to each well in 200 μl of RPMI medium. Cells were incubated for 20 h at 37 ∘C and 5% CO2. Supernatants were collected for cytotoxicity and ELISA analysis. A volume of 25 μl of 100 mM EDTA PBS was added to each well containing the cells and samples were incubated for 5 min at 37 ∘C and 5% CO2. Cells were detached by thoroughly pipetting each well and transferred to a 96-well V-bottom plate.

Lck chemical inhibition assay

U87 cells (50,000) in 100 μl of DMEM were seeded per well in a 96-well flat-bottom plate and incubated overnight. T cells were treated with the appropriate concentration of A-770041 for 1 h. The DMEM media were discarded and 50,000 A-770041-treated T cells were added to each well in 200 μl of RPMI media. Cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 ∘C and 5% CO2. Supernatants were collected for cytotoxicity and ELISA analysis, and T cells were analysed for activation markers as in other co-culture assays.

Flow cytometry

The following fluorophore-conjugated mAbs were used: CD45 (Biolegend, clone HI30), CD3 (Biolegend, clone OKT3), 4-1BB (Biolegend, clone 4B4-1), CD69 (Biolegend, clone FN50), CD8α (Biolegend, clone HIT8), CD4 (Biolegend, clone RPA-T4), CD43 (Biolegend, clone CD43-10G7), CD11α (Biolegend, clone TS2/4), CD5 (Biolegend, clone UCHT2), CD2 (Biolegend, clone TS1/8) and TCR Vβ13.1 (Biolegend, clone H131).

Cells were stained for 20 min at 4 ∘C, washed with PBS and analysed using a BD X-20 or a Cytoflex LX flow cytometer (Beckman Couter). Data were analysed using FlowJo v.10, RRID:SCR008520 (BD Biosciences) and GraphPad Prism, RRID:SCR002798 (GraphPad Software).

Cytotoxicity assay

Target cell lines were engineered to express the Nluc luciferase57. A 2 mM coelenterazine (CTZ) stock solution was prepared in methanol, aliquoted and stored at −80 ∘C. Supernatant from co-culture assays was mixed at a 1:1 ratio with PBS 10 μM CTZ, and luminescence was read using a SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Cytokine ELISA

Invitrogen Human IFNγ ELISA kits (ThermoFisher) were used following manufacturer protocol to quantify levels of cytokine in diluted T cell supernatant. A SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) was used to measure absorbances at 450 nm and 570 nm.

Longitudinal killing assay

mCherry positive A375 cells were seeded in a 96-well flat-bottom plate and incubated overnight in 100 μl of DMEM at 37 ∘C and 5% CO2. To normalize differences in TCR transduction across different batches, 50,000 a3a or c259 TCR positive T cells were used as the starting concentration, and they were serially diluted to the appropriate effector:target (E:T) ratios. For each E:T ratio, 100 μl of T cells were plated in triplicate. The mCherry positive A375 cell number was quantified every 2 h using an xCELLigence RTCA eSight system (Agilent).

Surface plasmon resonance

All SPR experiments were carried out at the Dunn School SPR facility using our published method24. The c259 TCR/pMHC steady-state binding affinities were measured on a Biacore T200 SPR system (GE Healthcare) with a CAP chip using HBS-EP as running buffer. The CAP chip was saturated with streptavidin and biotinylated pMHCs were immobilized to the desired level. A titration of the TCR was flowed through at 37 ∘C. The reference flow cell contained CD58 immobilized at levels matching those of pMHCs on the remaining flow cells. The signal from the reference flow cell was subtracted (single referencing) and the average signal from the closest buffer injection was subtracted (double referencing). Steady-state binding affinity was calculated by fitting the one site-specific binding model (Response = Bmax [TCR]/(KD + [TCR])) on GraphPad Prism to double-referenced equilibrium resonance units (RU) values. The Bmax was constrained to the inferred Bmax from the empirical standard curve generated by plotting the maximal binding of a conformationally sensitive pMHC antibody to the maximal TCR binding (Bmax).

Pooled 9-mer peptide library

A library of pooled randomly synthetized 9-mer peptides was produced by Peptide Protein Research. This library was composed of all natural amino acids, except cysteine, as previously described58. The library has a theoretical diversity of 199 peptides.

U87 cells (50,000) in 100 μl of DMEM were seeded per well in a 96-well flat-bottom plate and incubated overnight. The 9-mer pooled peptide library was diluted in DMEM to 100 μM, added to each well containing cells and incubated for 60 min at 37 ∘C and 10% CO2. T cells (50,000) were added to each well in 200 μl of RPMI medium. Cells were incubated for 20 h at 37 ∘C and 5% CO2. Supernatants were collected for cytotoxicity analysis. In each independent biological experiment, three technical measurements were taken and averaged.

Positional scanning peptide library SPR

To prepare pMHC complexes presenting the local peptide library, a disulfide-stabilized variant of the human MHC-I protein HLA-A*02:01 (DS-A2) was used59. The DS-A2 protein was produced as described previously59. Briefly, the DS-A2 and β2-microglobulin (β2m) subunits were produced in E. coli as inclusion bodies and solubilized in 8 M urea. The protein was then refolded in the presence of GlyLeu, a dipeptide that binds with low affinity to the peptide-binding cleft. The refolded DS-A2–β2m complexes were purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex S75 10/300 column (GE Healthcare/Cytiva) in HBS-EP buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA and 0.05% Tween 20). Local-library peptides were loaded by incubating the DS-A2–β2m complex with each peptide for 2 h at r.t. The pMHC complexes were stored at 4 ∘C until use within 24 h.

Soluble c259 TCR was produced as separate TCRα and TCRβ chains in E. coli. Both chains were recovered as inclusion bodies, solubilized in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 8 M urea and 2 mM dithiothreitol, and then stored in aliquots at −70 ∘C. For refolding, 30 mg of each TCR chain was added to 1 l of refolding buffer (150 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) 3 M urea, 200 mM Arg-HCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF) and stirred for 1 h at 4 ∘C. This was followed by dialysis in 10 l 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) buffer for 3 days in total, with the dialysis buffer changed after 1 day. The refolded c259 TCR was purified using anion exchange chromatography (HiTrap Q HP, Cytiva), followed by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 Increase, Cytiva) in HBS-EP buffer. Purified c259 was used within 48 h.

High-throughput affinity measurements of c259 TCR binding to MHC loaded with the peptide library were performed using LSA or LSAXT (Carterra). Each pMHC was immobilized via biotin–streptavidin binding on a different spot of the SAHC30M biosensor (Carterra) for 20 min, resulting in immobilization levels between 200 and 900 RUs. Measurements were performed in HBS-EP buffer at 37 ∘C. A 2-fold dilution series of c259 TCR was prepared in HBS-EP buffer, with the highest concentration between 100–130 μM. Starting with the highest dilution, increasing concentrations of c259 were injected over the chip for 5 min, followed by 5–10 min of dissociation, without regeneration. Afterwards, a β2m specific antibody (clone B2M-01 (ThermoFisher) or BBM.1 (Absolute Antibody)) was injected for 10 min. The resulting data were analysed using Kinetics Software (Carterra). Any spikes were removed from the data before referencing against empty control spots or spots immobilized with CD86 at matching immobilization levels. The final injection in a series 6 buffer injections before TCR injection was subtracted from the data for double referencing. Subsequently, the steady-state binding RU was calculated by taking the average RU from over 20 s.

Steady-state analysis was performed to obtain the TCR–pMHC affinity (KD) values. First, steady-state data were fitted with a one site-specific binding model (Response = Bmax [TCR]/(KD + [TCR])), with KD and Bmax unconstrained. We then constructed an empirical standard curve using high-affinity pMHCs (KD < 20 μM) to relate maximal anti-β2m binding to TCR Bmax. Next, steady-state data for all pMHCs were fitted with a one site-specific binding model, with Bmax constrained to the Bmax inferred from the empirical standard curve. We excluded KD values for peptides, where we observed little or no anti-β2m binding responses, indicating that the pMHC complex was unstable and lost the peptide over time (indicated as N/A in Supplementary Table 2). We further excluded KD values for pMHC that produced a TCR binding response of less than 5 RU (indicated as non-binders (NB) in Supplementary Table 2).

Data analysis

EC50 was calculated as the concentration of antigen required to elicit 50% of the maximum response determined for each condition individually, whereas P15 was calculated as the concentration of antigen required to elicit 15% of the maximum activation for the experiment.

We have used P15 for two reasons. First, P15 always corresponds to the concentration of peptide required to activate 15% of T cells, independent of the maximum responses. In contrast, EC50 is the concentration of peptide required to activate 50% of the maximum response (that is, normalized to the maximum of wild type or knockout). In other words, two antigens with the same antigen potency as measured by EC50 values may produce a different percentage of activated T cells if their maximum response (Emax) differ. In this case, the antigens would have different antigen potencies as defined by P15. Second, the use of P15 does not require the dose–response curve to saturate, enabling accurate estimates of P15 from lower-affinity interactions. This measure of potency was previously used in ref. 24 to study ligand discrimination.

The study is largely focused on comparing antigen sensitivity using EC50 or P15 measures, which we have found to display standard deviations of 0.2 (on log-transformed values). The smallest effective size that we aimed to resolve was 3-fold changes (a difference of 0.47 on log-transformed values), and a power calculation shows that this can be resolved with a power of 80% (⍺ at 0.05) using three samples in each group. Therefore, all experiments relied on a minimum of 3 independent donors.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Continue Reading

-

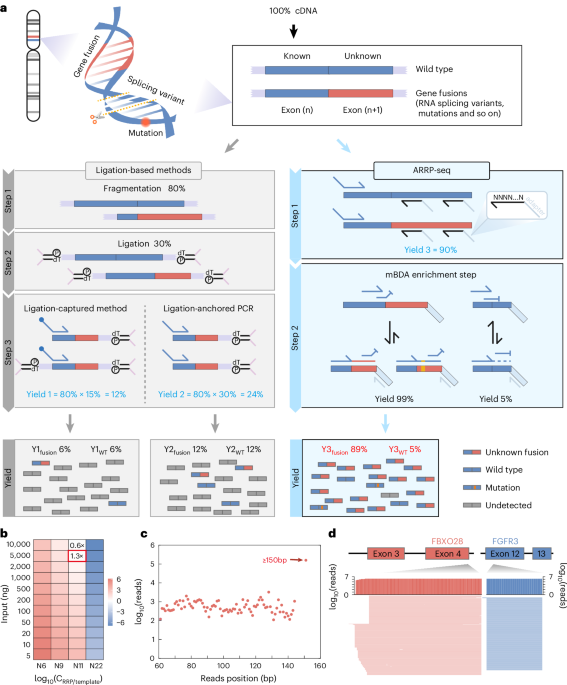

Anchored random reverse primer sequencing for quantitative detection of novel gene fusions

Gao, Q. et al. Driver fusions and their implications in the development and treatment of human cancers. Cell Rep. 23, 227–238.e3 (2018).

Google Scholar

…Continue Reading

-

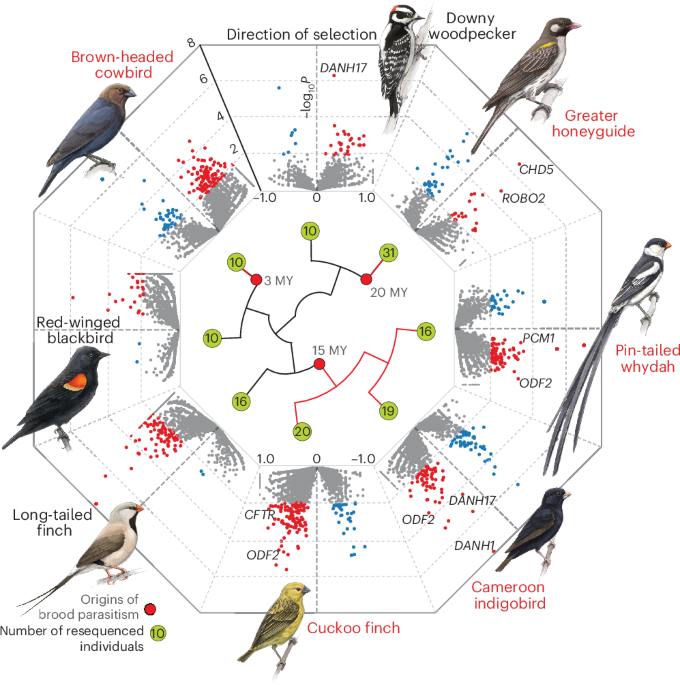

Repeated adaptation in sperm-related and neuronal genes in brood parasitic birds

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is a summary of: Osipova, E. et al. Comparative population genomics reveals convergent adaptation across…

Continue Reading

-

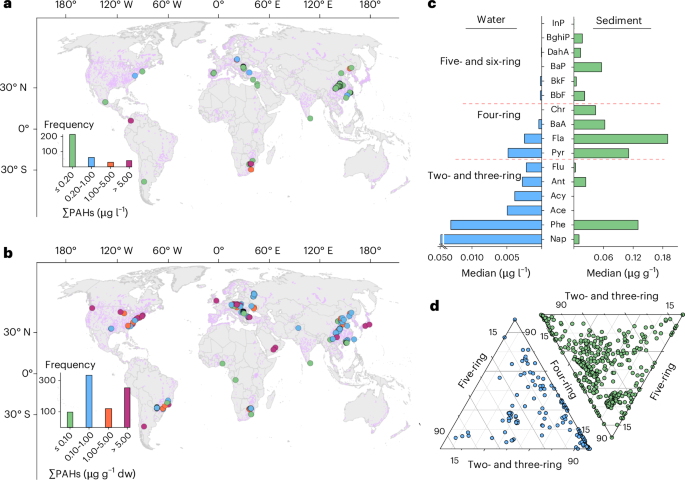

Regionally distinct threats from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in global reservoirs

Boström, C. E. et al. Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air. Environ. Health Perspect. 110, 451–488 (2002).

Kim, K. H., Jahan, S. A., Kabir, E. & Brown, R. J. A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects. Environ. Int. 60, 71–80 (2013).

Google Scholar

Shrivastavaa, M. et al. Global long-range transport and lung cancer risk from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons shielded by coatings of organic aerosol. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1246–1251 (2017).

Google Scholar

Babek, O. et al. Reservoir deltas and their role in pollutant distribution in valley-type dam reservoirs: Les Kralovstvi dam, Elbe River, Czech Republic. Catena 184, 104251 (2020).

Google Scholar

González-Gaya, B. et al. Biodegradation as an important sink of aromatic hydrocarbons in the oceans. Nat. Geosci. 12, 119–125 (2019).

Google Scholar

Li, R. F., Hua, P., Zhang, J. & Krebs, P. Effect of anthropogenic activities on the occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in aquatic suspended particulate matter: evidence from Rhine and Elbe rivers. Water Res. 179, 115901 (2020).

Google Scholar

Lv, M. et al. Human impacts on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon distribution in Chinese intertidal zones. Nat. Sustain. 3, 878–884 (2020).

Google Scholar

González-Gaya, B. et al. High atmosphere–ocean exchange of semivolatile aromatic hydrocarbons. Nat. Geosci. 9, 438–442 (2016).

Google Scholar

Cooley, S. W., Ryan, J. C. & Smith, L. C. Human alteration of global surface water storage variability. Nature 591, 78–81 (2021).

Google Scholar

Janssen, A. B. G. et al. Shifting states, shifting services: Linking regime shifts to changes in ecosystem services of shallow lakes. Freshwater Biol. 66, 1–12 (2020).

Google Scholar

Janssen, A. B. G. et al. Characterizing 19 thousand Chinese lakes, ponds and reservoirs by morphometric, climate and sediment characteristics. Water Res. 202, 117427 (2021).

Google Scholar

Li, D. F. et al. High Mountain Asia hydropower systems threatened by climate-driven landscape instability. Nat. Geosci. 15, 520–530 (2022).

Google Scholar

Ryan, J. C., Smith, L. C., Cooley, S. W., Pitcher, L. H. & Pavelsky, T. M. Global characterization of inland water reservoirs using ICESat-2 altimetry and climate reanalysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088543 (2020).

Google Scholar

Cooley, S. W. Global loss of lake water storage. Science 380, 693 (2023).

Google Scholar

Seopela, M. P., McCrindle, R. I., Combrinck, S. & Augustyn, W. Occurrence, distribution, spatio-temporal variability and source identification of n-alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water and sediment from Loskop dam, South Africa. Water Res. 186, 116350 (2020).

Google Scholar

Wilcke, W. Global patterns of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soil. Geoderma 141, 157–166 (2007).

Google Scholar

Chamberlain, K. J., Lehnert, K. A., McIntosh, I. M., Morgan, D. J. & Wörner, G. Time to change the data culture in geochemistry. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 737–739 (2021).

Google Scholar

Janssen, A. B. G. et al. Exploring, exploiting and evolving diversity of aquatic ecosystem models: a community perspective. Aquat. Ecol. 49, 513–548 (2015).

Google Scholar

Spake, R. et al. Implications of scale dependence for cross-study syntheses of biodiversity differences. Ecol. Lett. 24, 374–390 (2021).

Google Scholar

Laubmeier, A. N. et al. Ecological dynamics: integrating empirical, statistical, and analytical methods. Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 1090–1099 (2020).

Google Scholar

Gurevitch, J., Koricheva, J., Nakagawa, S. & Stewart, G. Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature 555, 175–182 (2018).

Google Scholar

Nakagawa, S., Yang, Y. F., Macartney, E. L., Spake, R. & Lagisz, M. Quantitative evidence synthesis: a practical guide on meta-analysis, meta-regression, and publication bias tests for environmental sciences. Environ. Evidence 12, 8 (2023).

Google Scholar

Pizzini, S. et al. PAHs, PCBs, PBDEs, and OCPs trapped and remobilized in the Lake of Cavazzo (NE Italy) sediments: temporal trends, quality, and sources in an area prone to anthropogenic and natural stressors. Environ. Res. 213, 113573 (2022).

Google Scholar

Yoon, S. J. et al. Large-scale monitoring and ecological risk assessment of persistent toxic substances in riverine, estuarine, and coastal sediments of the Yellow and Bohai seas. Environ. Int. 137, 105517 (2020).

Google Scholar

Baskaran, D. & Byun, H. Current trend of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon bioremediation: mechanism, artificial mixed microbial strategy, machine learning, ground application, cost and policy implications. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155334 (2024).

Google Scholar

Yunker, M. B. et al. PAHs in the Fraser River basin: a critical appraisal of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Org. Geochem. 34, 489–515 (2002).

Google Scholar

Liu, D. et al. Data-driven insights into the contamination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in marine bays. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 15202–15213 (2024).

Google Scholar

Li, W. W. et al. Spatiotemporal occurrence, sources and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a typical mariculture ecosystem. Water Res. 204, 117632 (2021).

Google Scholar

Vilanova, R. M., Fernández, P., Martı́nez, C. & Grimalt, J. O. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in remote mountain lake waters. Water Res. 35, 3916–3926 (2001).

Google Scholar

Hadibarata, T., Syafiuddin, A. & Ghfar, A. A. Abundance and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in sediments of the Mahakam River. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 149, 110650 (2019).

Google Scholar

Bigus, P., Tobiszewski, M. & Namieśnik, J. Historical records of organic pollutants in sediment cores. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 78, 26–42 (2014).

Google Scholar

Hites, R. A., Laflamme, R. E. & Farrington, J. W. Sedimentary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: the historical record. Science 198, 829–831 (1977).

Google Scholar

Guo, J. Y., Chen, J. G. & Wang, J. F. Sedimentary records of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in China: a comparison to the worldwide. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 1612–1667 (2017).

Google Scholar

Wang, W. W., Xu, J. L., Qu, X. L., Lin, D. H. & Yang, K. Current and future trends of low and high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface water and sediments of China: insights from their long-term relationships between concentrations and emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 3397–3406 (2022).

Google Scholar

Martins, C. C. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a large South American industrial coastal area (Santos Estuary, southeastern Brazil): sources and depositional history. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 63, 452–458 (2011).

Google Scholar

Jones, K., Sanders, G., Wild, S. R., Burnett, V. & Johnston, A. E. Evidence for a decline of PCBs and PAHs in rural vegetation and air in the United Kingdom. Nature 356, 137–140 (1992).

Google Scholar

Kuempel, C. D. Sedimentation sifted out of pollution priorities. Science 379, 1098–1099 (2023).

Google Scholar

Shen, H. Z. et al. Global atmospheric emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from 1960 to 2008 and future predictions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 6415–6424 (2013).

Google Scholar

McDonough, C. A., Khairy, M. A., Muir, D. C. G. & Lohmann, R. Significance of population centers as sources of gaseous and dissolved PAHs in the lower great lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7789–7797 (2014).

Google Scholar

Abbott, B. W. et al. Human domination of the global water cycle absent from depictions and perceptions. Nat. Geosci. 12, 533–540 (2019).

Google Scholar

Ramirez-Castaneda, V. et al. A set of principles and practical suggestions for equitable fieldwork in biology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2122667119 (2022).

Google Scholar

Spake, R. et al. Improving quantitative synthesis to achieve generality in ecology. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1818–1828 (2022).

Google Scholar

González-Gaya, B., Zuniga-Rival, J., Ojeda, M. J., Jimenez, B. & Dachs, J. Field measurements of the atmospheric dry deposition fluxes and velocities of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to the global oceans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 5583–5592 (2014).

Google Scholar

Guo, Z. F. et al. Global meta-analysis of microplastic contamination in reservoirs with a novel framework. Water Res. 207, 117828 (2021).

Google Scholar

Hoel, E. P., Albantakis, L. & Tononi, G. Quantifying causal emergence shows that macro can beat micro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 10, 19790–19795 (2013).

Google Scholar

Khelifa, R. & Mahdjoub, H. An intersectionality lens is needed to establish a global view of equity, diversity and inclusion. Ecol. Lett. 25, 1049–1054 (2022).

Google Scholar

Zipkin, E. F. et al. Addressing data integration challenges to link ecological processes across scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 19, 30–38 (2021).

Google Scholar

Husic, B. E. & Pande, V. S. Ward clustering improves cross-validated Markov state models of protein folding. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 963–967 (2017).

Google Scholar

Ward, J. H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 236–244 (1963).

Google Scholar

Wang, J. F. et al. Geographical detectors-based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 24, 107–127 (2010).

Google Scholar

Guo, Z. F. et al. Regionally distinct threats from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in global reservoirs. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30626969 (2025).

Continue Reading

-

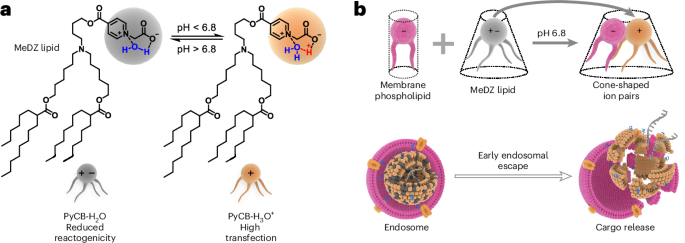

Zwitterionic lipid design enhances mRNA cancer vaccine efficacy and reduces reactogenicity

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is a summary of: Zhao, Y. et al. Low reactogenicity and high tumour antigen expression from mRNA-LNPs…

Continue Reading

-

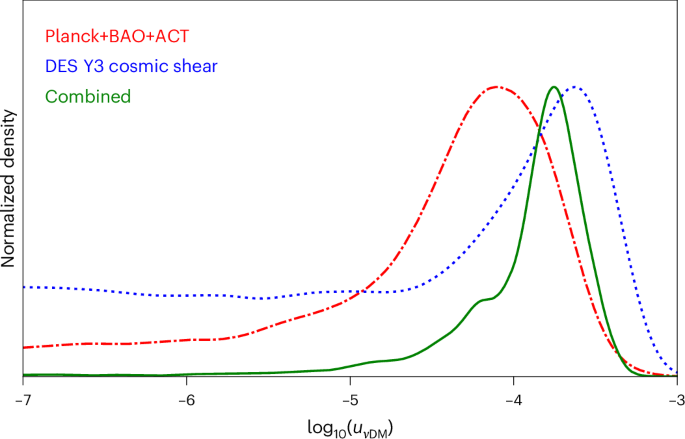

A solution to the S8 tension through neutrino–dark matter interactions

Roszkowski, L., Sessolo, E. M. & Trojanowski, S. WIMP dark matter candidates and searches—current status and future prospects. Rept. Prog. Phys. 81, 066201 (2018).

Google Scholar

…Continue Reading

-

Health visitors to help vaccinate children ‘facing barriers’ under new pilot

Health visitors in some areas are set to offer vaccinations to children who have ‘fallen through the cracks’ as part of a one-year pilot programme.

The government has unveiled plans for a £2m pilot where health visitors will…

Continue Reading