A global music icon, Laura Pausini will be one of the superstar performers of the Opening Ceremony of the Milano Cortina 2026 Olympic Winter Games, taking place on 6 February 2026 at the San Siro Olympic Stadium in Milano.

The only Italian artist…

A global music icon, Laura Pausini will be one of the superstar performers of the Opening Ceremony of the Milano Cortina 2026 Olympic Winter Games, taking place on 6 February 2026 at the San Siro Olympic Stadium in Milano.

The only Italian artist…

TBS Report

02 January, 2026, 05:40 pm

Last modified: 02 January, 2026, 05:50 pm

Direct air connectivity between Pakistan and Bangladesh is set to resume after…

As a cultural historian who has worked with and lectured on the drinks industry for many years I was asked to write a book about post-war Britain and the drinks that made it. I immediately knew I had to include Babycham – a post-austerity tipple that had made Britain smile.

Britain in the early 1950s was gradually emerging from the shadow of war and was dealing with bankruptcy and post-war shortages. By the time of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953, British manufacturing was getting back on its feet.

In that year, a little-known Somerset brewery, Showerings, hit upon a novel idea: offer cash-strapped Britons sick of the grey years of austerity a festive, sparkling alcoholic tipple that was cheap but fun. Thus was born Babycham, the celebratory drink that looked like champagne, but wasn’t.

I have distinct memories of my mum drinking the sparkling beverage in the 1960s, sometimes with brandy as a cheap, working-class alternative to the classic champagne cocktail. And who can forget those wonderful, deer-themed champagne coupes which Babycham distributed, and which are now collectors’ items.

As I write in my book Another Round, it was originally named “Champagne de la Poire” by its creators, Francis and Herbert Showering of Shepton Mallet in Somerset. Babycham was a new alcoholic perry – a cider made from pears. It had the modest strength of 6% alcohol-by-volume and came in both full-sized bottles and fashionable, handbag-sized four- and two-ounce versions.

At sixpence a bottle, Babycham’s bubbles come at a fraction of the price of genuine French bubbly – a luxury that very few could afford. Babycham came to epitomise the brave new world of mid-1950s Britain – British ingenuity still seemed to lead the world, and anything seemed possible.

Babycham’s innovative brand design, marketing methods and advertising techniques brought flashy and flamboyant American techniques to the staid world of British beverages as its makers exploited not just the expanding potential of magazines and radio but, crucially, the revolutionary medium of television advertising. Perhaps most importantly, it was also the first British alcoholic drink to be aimed squarely at women.

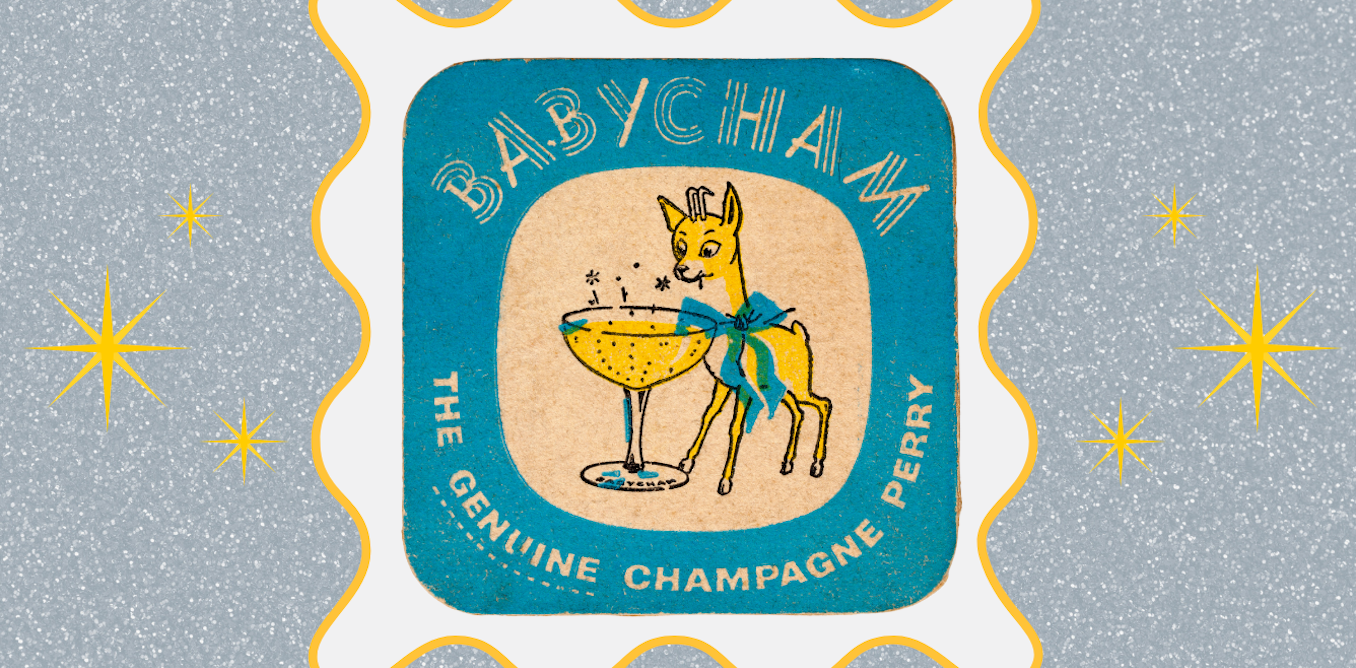

Showerings and their advertising guru Jack Wynne-Williams made Babycham into the first British consumable to be introduced through advertising and marketing, rather than marketing an existing product. Their eye-catching new baby deer logo featured in the ad campaign of autumn 1953 and has been with us ever since. And it was equally prominent when their groundbreaking debut TV ad in 1956 made Babycham the first alcoholic brand to be advertised on British television.

In order to convey the idea that Babycham provided a champagne lifestyle at a beer price, Showerings advised their (largely female) customers that it was best served in an attractive and undeniably feminine French champagne coupe. Coupes were soon being customised by Showerings, who plastered them with the brand’s distinctive new deer logo and thereby created an instant kitsch collectable. In this way, Babycham offered the aspirational female Briton of the 50s and 60s a fleeting illusion of glamour and sophistication at the price of an average pub tipple.

All of this Americanised marketing paid handsome dividends. Babycham’s sales tripled between 1962 and 1971. These bumper sales enabled the Showerings to be acquired by drinks leviathan Allied Breweries in 1968, and after the merger Francis Showering was appointed as a director of the new company.

It was only in the early 1980s that Babycham’s sales began first to fall, and then to plummet. During this decade the drinks market was becoming more sophisticated and diverse. Women were turning more to wine and cocktails than to retro tipples made from sparkling pear juice.

However, after a period in the doldrums, the Babycham brand is back. In 2016, a younger generation of Showerings bought back the family’s original cider mill in Shepton Mallet and sought to revive their famous sparkling perry, relaunching Babycham in 2021.

If it is remembered at all, it’s now associated with celebrations such as birthdays or Christmas. No longer seen as a regular indulgence. The Babycham brand and its winsome fawn logo do seem rather old-fashioned today but in an age of nostalgia for the Britain of the past it could be ripe for a renaissance.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

As China heads into the new year it will start rolling out its 15th five‑year plan, this one is for 2026-2030.

Beijing is doubling down on greening its economy, and aims to hit two major climate goals: “carbon peaking”, where carbon dioxide emissions have reached a ceiling by 2030, and “carbon neutrality”, where net carbon dioxide emissions have been driven down to zero by 2060.

Yet, China’s green push sits uneasily with its energy realities: coal still provides about 51% of its electricity as of mid‑2025, underpinning China’s difficulty in greening its energy system swiftly. Here are five major challenges that will shape China’s green transition as it moves into 2026.

Imagine standing in western China (for instance in Tibet, Xinjiang and Qinghai), which produces a lot of solar and wind energy. On bright and windy days, these installations generate vast amounts of clean electricity. Yet much of that power goes to waste.

China’s grid can only handle a limited load, and when renewable generation peaks, it risk overloading the power network. So grid operators respond by telling energy producers to dial down output, which is a process called “curtailement”. The result is that electricity from the west often fails to reach eastern economic hubs, such as Beijing, Tianjin, Shandong, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong, where demand is greatest.

China needs to invest heavily in the ways to transport and store excess energy. The State Grid Corporation of China claims that it will be spending 650 billion yuan (£69 billion) in 2025 to upgrade the power network, and perhaps much more in subsequent years.

The challenge here is sustaining these capital-intensive projects while the broader economy still grapples with the lasting effects of the 2021 property crisis.

Even as China vows to go green and be a world leader in environmental energy, it continues to expand its coal capacity, and has added enough new coal-fired power stations in 2024 to power the UK twice over per annum. This apparent contradiction stems from concerns over energy security.

Beijing is determined to avoid a repeat of the blackouts and power shortages of 2020–2022. Coal provides dependable, round‑the‑clock power that renewables cannot yet fully replace. Yet the steady expansion of coal capacity undercuts China’s climate pledges and highlights ongoing tensions between China’s president, Xi Jinping’s, dual carbon goals and the country’s pressing energy demands, which raises questions about how far political ambition can stretch against economic reality.

China’s vast manufacturing strength, which was once an asset, is now posing a problem. The rapid expansion of solar, wind, and electric vehicle industries has created overcapacity across the clean‑tech sector. Factories are producing more panels, turbines, and batteries than the domestic market can absorb. This has created a cut-throat price war, where companies sell at below cost price, which erodes company profits.

Beijing must find a balance between restraining overproduction without choking growth in green industries. This balancing act is politically sensitive, as local governments depend on these industries to create jobs (7.4 million in 2023), and generate substantial revenue. It was estimated that in 2024 green industries contributed 13.6 trillion yuan to China’s economy or 10% of the country’s GDP.

China’s surplus of clean tech such as cheap solar panels, electric vehicles (EVs), and batteries, have triggered trade tensions abroad. In 2023 and 2024, the European Union investigated allegations of Chinese subsidies being poured into EVs, wind turbines and solar panels. Tariffs of up to 35.3% were placed on Chinese EVs. However, tariffs on Chinese solar panels and wind turbines have not been imposed so far.

But, on January 1 2026 the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) comes into effect. The CBAM is a carbon tax that Europeans will pay if imported goods are made using high carbon emissions. While the tax does not explicitly target EVs and solar panels, it will cover carbon-intensive materials used in their production, such as steel and aluminium, which are made using coal-fired plants.

What this means is Chinese clean tech might lose its competitive edge in the European market as customers are driven away from its products. Industrial players might rely on exports to stay afloat given the highly competitive nature of China’s domestic green market, but the CBAM is likely to undermine China’s green industry.

Chinese local governments are formally responsible for putting Beijing’s climate policies into practice, but many are expected to implement these policies largely on their own. While provincial authorities typically have more fiscal resources and technical expertise, city-level governments within each province often don’t have the funds to do so, which makes it difficult to deliver on green initiatives in practice.

At the same time, even when local authority leaders are told to achieve climate‑related targets, their career advancement remains closely linked to conventional economic performance indicators such as GDP growth and investment.

All of this helps explain the continued enthusiasm for new coal‑fired power projects. They are framed not only as a fail‑safe in case renewables and grids cannot meet rising demand, but also as avenues for local employment, fixed‑asset investment and fiscal revenue.

China’s continued greening in 2026 will be challenged by all of these issues.

Multi-hyphenate artist Donald Glover, also known by his stage name Childish Gambino, has five Grammy Awards, two Emmys and, at 42, one stroke.

“I was doing this world tour,” he said at a November concert…

The proliferation of artificial intelligence technologies, molecular manipulation and literal sea changes are among the top issues a team of conservation experts anticipate will affect biodiversity in the year ahead and beyond,…

Built with CopprLink cabling, Gen5 signal retimers, and a 1300W PSU to support high-TDP GPUs and reduce throttling.

HighPoint Technologies, Inc. has announced the RocketStor 8631D, an external accelerator enclosure designed to provide PCIe…

astronaut: Someone trained to travel into space for research and exploration.

attention: The phenomenon of focusing mental resources on a specific object or event.

cognitive: A term that relates to mental activities, such as thinking,…

If back pain can be reliably prevented, not only will quality of life be improved, but it will also directly lead to a reduction in health care costs for society as a whole. According to the research team, back pain is one of the most common…