- PPP Chairman inaugurates ICU at Children’s Hospital in Larkana RADIO PAKISTAN

- Bilawal inaugurates Indus University Hospital in Korangi Dawn

- Health sector in Sindh offering better services than other provinces: Bilawal 24 News HD

- State’s…

Author: admin

-

PPP Chairman inaugurates ICU at Children's Hospital in Larkana – RADIO PAKISTAN

-

Plans for new Maidstone town council reach second stage

The borough council said the area under review currently has an electorate of around 64,000 people, with 60,000 in the unparished area.

It said it had also taken into consideration potential impacts of upcoming local government reorganisation,…

Continue Reading

-

National economy heading towards progress: Tanveer – RADIO PAKISTAN

- National economy heading towards progress: Tanveer RADIO PAKISTAN

- 2025 OUTLOOK : Tax relief held fast by IMF restraints Dawn

- Who is making money in Pakistan? Business Recorder

- The flip side The Express Tribune

- 2.7% economic growth not enough to…

Continue Reading

-

Hidden quantum spin liquid behavior confirmed in a new kagome crystal

Deep inside some magnetic materials, electrons can behave in ways that seem to defy common sense. Instead of lining up neatly like tiny compass needles, as magnets usually do, their spins remain restless, fluctuating endlessly even near absolute…

Continue Reading

-

DPM reaffirms Pakistan's full support for Somalia's sovereignty – RADIO PAKISTAN

- DPM reaffirms Pakistan’s full support for Somalia’s sovereignty RADIO PAKISTAN

- Pakistan reaffirms full support for Somalia’s sovereignty, territorial integrity samaa tv

- DPM Dar reaffirms Pakistan’s full support for Somalia’s sovereignty Dunya…

Continue Reading

-

Man dead after shooting at Lamar Avenue gas station, one detained, police say – Citizen Tribune

- Man dead after shooting at Lamar Avenue gas station, one detained, police say Citizen Tribune

- Benazir’s death anniversary observed at assassination site Dawn

- PPP vows to carry forward BB’s mission The Express Tribune

- Price of democracy Geo…

Continue Reading

-

Bilawal Bhutto urges PTI to shun ‘extremist politics’, return to democratic norms

PPP chairman calls on PTI to return to democratic politics, says it will benefit the party and its leaders

Pakistan Peoples Party Chairperson Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari delivers a video address on the party’s 58th foundation day, Sunday, Nov 30,…

Continue Reading

-

Why It Took Pakistan So Long To Sell JF-17 Fighters To An Arab Country – Forbes

- Why It Took Pakistan So Long To Sell JF-17 Fighters To An Arab Country Forbes

- Pakistan strikes $4 billion deal to sell weapons to Libyan force, officials say Reuters

- Libya’s Grand Mufti decries Pakistan-Haftar military deal as unethical, urges…

Continue Reading

-

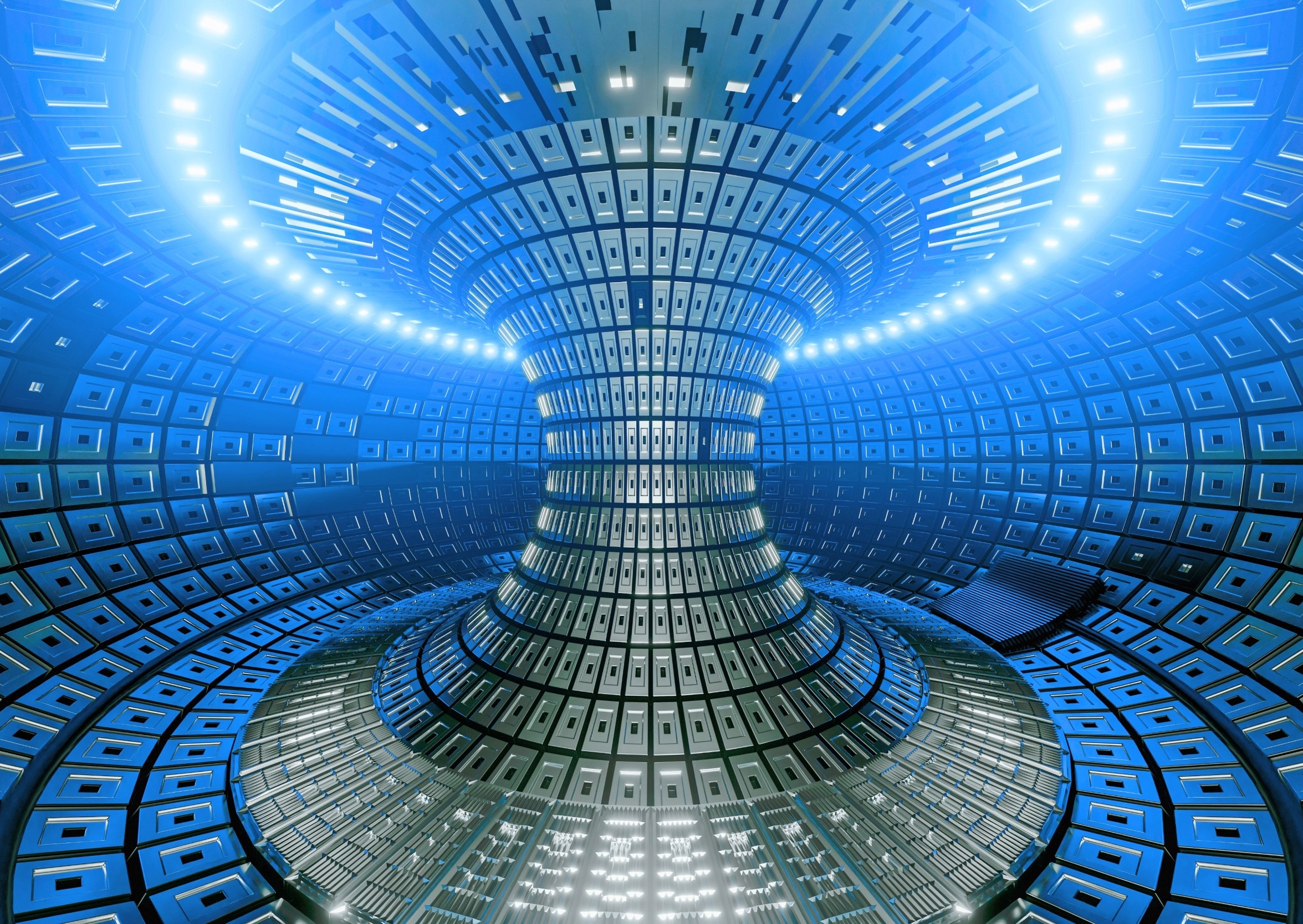

Fusion reactors may create dark matter particles in their walls

Fusion reactors are designed to produce clean energy, but new theory suggests they could also generate one of physics’ most elusive particles.

A proposal from U.S. researchers argues that large fusion plants may inadvertently create axions –…

Continue Reading

-

This Is the Best Time of Day to Drink Coffee for Longevity

- There is a strong link between the time of day that people drink coffee and their longevity, according to one study.

- Researchers found that morning coffee drinkers had a lower all-cause mortality risk and a lower risk of heart disease compared to…

Continue Reading