- Dalian iron ore extends gains on easier home buying in Beijing Business Recorder

- MMi Daily Iron Ore Report (December 24) Shanghai Metals Market

- Iron Ore Holds Rebound from 5-Month Low TradingView — Track All Markets

- Dalian iron ore extends gains on tight BHP supply, firmer hot metal production Mining.com

- Iron ore futures slip Business Recorder

Author: admin

-

Dalian iron ore extends gains on easier home buying in Beijing – Business Recorder

-

Food bank scheme gives parents choice at Christmas

Naila, 45, a mum-of-four living in temporary accommodation, added: “I’m homeless and I can’t afford a present – everything is really expensive.

“When I saw the presents I felt happy because it meant my kids would be happy.”

Volunteers decorated…

Continue Reading

-

Did a big night out make us ‘paint the town red’?

Mr Fare said if it wasn’t for a misfire the toll keeper would have shot at the group.

But that did not stop them from continuing their night out.

“They screwed the shutters shut, painted them red then came all the way through town daubing various…

Continue Reading

-

Virtual reality opens doors for older people to build closer connections in real life

LOS GATOS, Calif. — Like many retirement communities, The Terraces serves as a tranquil refuge for a nucleus of older people who no longer can travel to faraway places or engaging in bold adventures.

But they can still be thrust back to their…

Continue Reading

-

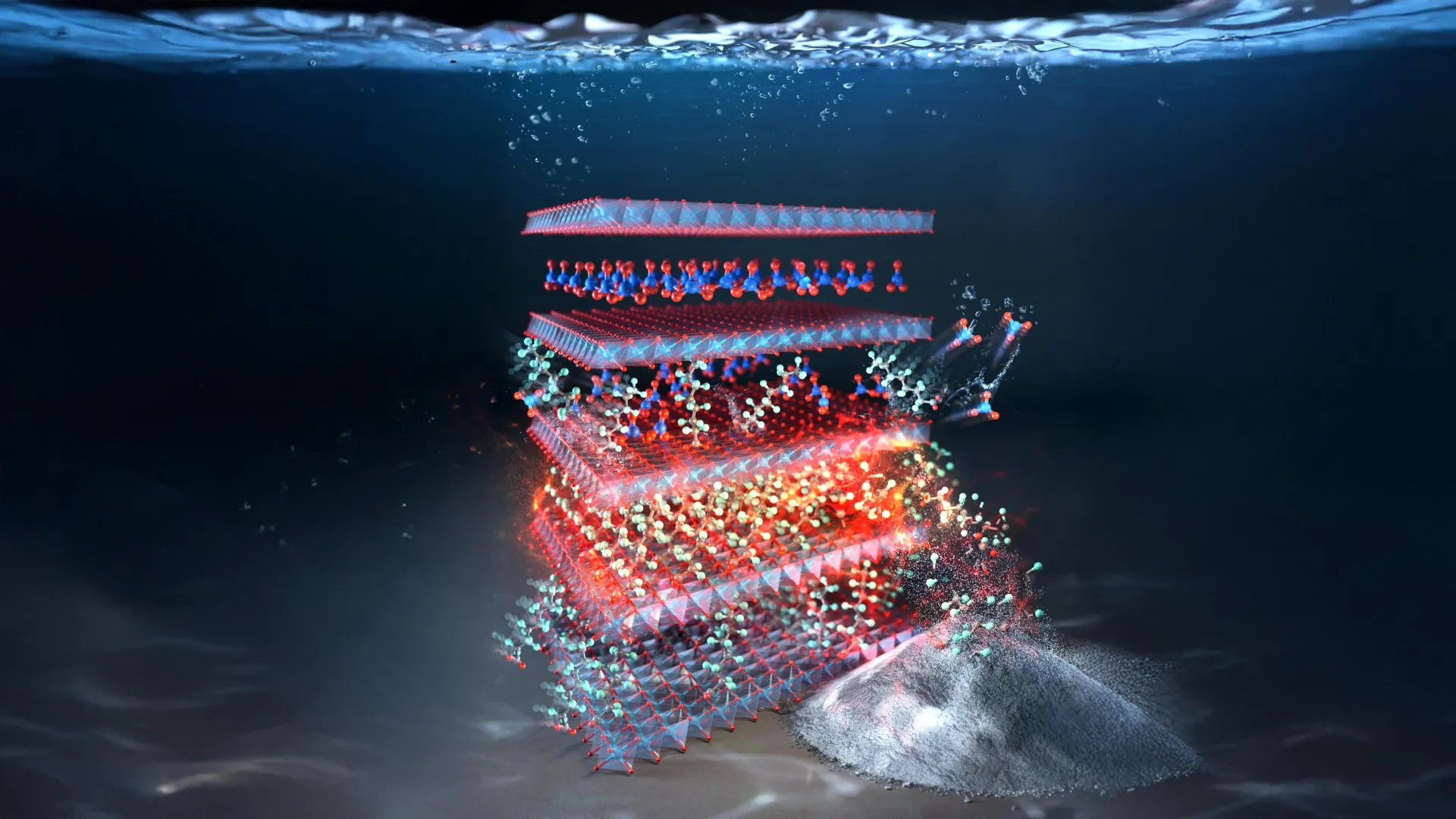

New technology eliminates “forever chemicals” with record-breaking speed and efficiency

A research team at Rice University, working with international collaborators, has created the first environmentally friendly technology that can quickly trap and break down toxic “forever chemicals” (PFAS) in water. The results, published…

Continue Reading

-

Inverse design of cellular structures with the targeted nonlinear mechanical response

Bezek, L. B. et al. Effect of part size, displacement rate, and aging on compressive properties of elastomeric parts of different unit cell topologies formed by vat photopolymerization additive manufacturing. Polymers 16, 3166 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Additive manufacturing of metal cellular structures: design and fabrication. Jom 67, 608–615 (2015).

Lin, H. et al. 3d printing of porous ceramics for enhanced thermal insulation properties. Adv. Sci. 12, 2412554 (2025).

Schaedler, T. A. et al. Designing metallic microlattices for energy absorber applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 16, 276–283 (2014).

Schaedler, T. A. & Carter, W. B. Architected cellular materials. Annual Rev. Mater. Res. 46, 187–210 (2016).

Boursier Niutta, C., Ciardiello, R. & Tridello, A. Experimental and numerical investigation of a lattice structure for energy absorption: application to the design of an automotive crash absorber. Polymers 14, 1116 (2022).

Mohsenizadeh, M., Gasbarri, F., Munther, M., Beheshti, A. & Davami, K. Additively-manufactured lightweight metamaterials for energy absorption. Mater. Des. 139, 521–530 (2018).

Uribe-Lam, E., Treviño-Quintanilla, C. D., Cuan-Urquizo, E. & Olvera-Silva, O. Use of additive manufacturing for the fabrication of cellular and lattice materials: a review. Mater. Manuf. Process. 36, 257–280 (2021).

Mueller, J., Raney, J. R., Shea, K. & Lewis, J. A. Architected lattices with high stiffness and toughness via multicore-shell 3d printing. Adv.Mater. 30, 1705001 (2018).

Lei, H. et al. Evaluation of compressive properties of slm-fabricated multi-layer lattice structures by experimental test and \(\mu\)-ct-based finite element analysis. Materi. Des. 169, 107685 (2019).

Kumar, A., Collini, L., Daurel, A. & Jeng, J.-Y. Design and additive manufacturing of closed cells from supportless lattice structure. Additive Manuf. 33, 101168 (2020).

Nakarmi, S. et al. The role of unit cell topology in modulating the compaction response of additively manufactured cellular materials using simulations and validation experiments. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 32, 055029 (2024).

Nakarmi, S. et al. Mesoscale simulations and validation experiments of polymer foam compaction-volume density effects. Mater. Lett. 382, 137864 (2025).

Xia, L. & Breitkopf, P. Design of materials using topology optimization and energy-based homogenization approach in matlab. Struct. Multidisciplinary Optim. 52, 1229–1241 (2015).

Radman, A., Huang, X. & Xie, Y. Topology optimization of functionally graded cellular materials. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 1503–1510 (2013).

Bauer, J., Hengsbach, S., Tesari, I., Schwaiger, R. & Kraft, O. High-strength cellular ceramic composites with 3d microarchitecture. Procd. National Acad. Sci. 111, 2453–2458 (2014).

Nguyen, J., Park, S.-I. & Rosen, D. Heuristic optimization method for cellular structure design of light weight components. Int. J. Precision Eng. Manuf. 14, 1071–1078 (2013).

Meier, T. et al. Obtaining auxetic and isotropic metamaterials in counterintuitive design spaces: an automated optimization approach and experimental characterization. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 3 (2024).

Vangelatos, Z. et al. Strength through defects: A novel bayesian approach for the optimization of architected materials. Sci. Adv. 7, eabk2218 (2021).

Ramesh, A. et al. Zero-shot text-to-image generation. In International conference on machine learning, 8821–8831 (Pmlr, 2021).

Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C. & Chen, M. Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.061251, 3 (2022).

Yao, Z. et al. Inverse design of nanoporous crystalline reticular materials with deep generative models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 76–86 (2021).

Sanchez-Lengeling, B. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science 361, 360–365 (2018).

Zhavoronkov, A. et al. Deep learning enables rapid identification of potent ddr1 kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1038–1040 (2019).

Liao, W., Lu, X., Fei, Y., Gu, Y. & Huang, Y. Generative ai design for building structures. Autom. Construct. 157, 105187 (2024).

Kingma, D. P., Welling, M. et al. Auto-encoding variational bayes (2013).

Goodfellow, I. J. et al. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 27 (2014).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 6840–6851 (2020).

Sohn, K., Lee, H. & Yan, X. Learning structured output representation using deep conditional generative models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 28 (2015).

Mirza, M. & Osindero, S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1411.1784 (2014).

Dhariwal, P. & Nichol, A. Diffusion models beat gans on image synthesis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 8780–8794 (2021).

Lee, D., Chen, W., Wang, L., Chan, Y.-C. & Chen, W. Data-driven design for metamaterials and multiscale systems: a review. Adv. Mater. 36, 2305254 (2024).

Zheng, X., Zhang, X., Chen, T.-T. & Watanabe, I. Deep learning in mechanical metamaterials: from prediction and generation to inverse design. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302530 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Deep generative modeling for mechanistic-based learning and design of metamaterial systems. Comput. Methods App. Mech. Eng. 372, 113377 (2020).

Zheng, L., Karapiperis, K., Kumar, S. & Kochmann, D. M. Unifying the design space and optimizing linear and nonlinear truss metamaterials by generative modeling. Nat. Commun. 14, 7563 (2023).

Tian, J., Tang, K., Chen, X. & Wang, X. Machine learning-based prediction and inverse design of 2d metamaterial structures with tunable deformation-dependent poisson’s ratio. Nanoscale 14, 12677–12691 (2022).

Zheng, X., Chen, T.-T., Guo, X., Samitsu, S. & Watanabe, I. Controllable inverse design of auxetic metamaterials using deep learning. Mater. Des. 211, 110178 (2021).

Challapalli, A., Patel, D. & Li, G. Inverse machine learning framework for optimizing lightweight metamaterials. Materi. Des. 208, 109937 (2021).

Vlassis, N. N. & Sun, W. Denoising diffusion algorithm for inverse design of microstructures with fine-tuned nonlinear material properties. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 413, 116126 (2023).

Bastek, J.-H. & Kochmann, D. M. Inverse design of nonlinear mechanical metamaterials via video denoising diffusion models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1466–1475 (2023).

Meier, T. et al. Scalable phononic metamaterials: Tunable bandgap design and multi-scale experimental validation. Mater. Des. 252, 113778 (2025).

Kumar, S., Tan, S., Zheng, L. & Kochmann, D. M. Inverse-designed spinodoid metamaterials. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 73 (2020).

Nakarmi, S., Leiding, J. A., Lee, K.-S. & Daphalapurkar, N. P. Predicting non-linear stress-strain response of mesostructured cellular materials using supervised autoencoder. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 432, 117372 (2024).

McNeel, R. et al. Grasshopper-algorithmic modeling for rhino. http://www.grasshopper3d.com (2013).

Dassault Systèmes. Abaqus Analysis User’s Manual, Version 2020 (2020).

Mooney, M. A theory of large elastic deformation. J. Appl. Phys. 11, 582–592 (1940).

Rivlin, R. Large elastic deformations of isotropic materials. i. fundamental concepts. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. London. Series A, Math. Phys. Sci. 240, 459–490 (1948).

Abdi, H. & Williams, L. J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Rev. Comput. Statist. 2, 433–459 (2010).

Yang, C., Kim, Y., Ryu, S. & Gu, G. X. Prediction of composite microstructure stress-strain curves using convolutional neural networks. Mater. Des. 189, 108509 (2020).

Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Int. Conference Mach. Learn., 448–456 (pmlr, 2015).

Li, X., Chen, S., Hu, X. & Yang, J. Understanding the disharmony between dropout and batch normalization by variance shift. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2682–2690 (2019).

Kullback, S. & Leibler, R. A. On information and sufficiency. Annals Math. Statist. 22, 79–86 (1951).

Higgins, I. et al. Early visual concept learning with unsupervised deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05579 (2016).

Fu, H. et al. Cyclical annealing schedule: A simple approach to mitigating kl vanishing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.10145 (2019).

Smith, S. L., Kindermans, P.-J., Ying, C. & Le, Q. V. Don’t decay the learning rate, increase the batch size. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.00489 (2017).

Liu, Y., Neophytou, A., Sengupta, S. & Sommerlade, E. Relighting images in the wild with a self-supervised siamese auto-encoder. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 32–40 (2021).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Dice, L. R. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology 26, 297–302 (1945).

Zhao, F., Huang, Q. & Gao, W. Image matching by normalized cross-correlation. In 2006 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics Speech and Signal Processing Proceedings, vol. 2, II–II (IEEE, 2006).

Continue Reading

-

‘Why our village nativity only has two wise men’

This year, people have been puzzled by the absence of a third wise man.

“There’s been a lot of stuff on Facebook saying ‘where’s the third wise man gone?’ Well, there never was a third one,” she clarified.

“There was this story going around…

Continue Reading

-

Albanese announces bravery award for heroes of Bondi antisemitic attack

NEWCASTLE, Australia — Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced plans Thursday for a national bravery award to recognize civilians and first responders who confronted “the worst of evil” during an antisemitic terror attack that…

Continue Reading

-

Front-runner to be Bangladesh PM returns after 17 years in exile

Tarique Rahman, the front-runner to be the next prime minister of Bangladesh, has returned to the country after 17 years in exile ahead of landmark general elections.

The 60-year-old is the figurehead of the influential Zia family and the son of…

Continue Reading

-

Front-runner to be Bangladesh PM returns after 17 years in exile

Tarique Rahman, the front-runner to be the next prime minister of Bangladesh, has returned to the country after 17 years in exile ahead of landmark general elections.

The 60-year-old is the figurehead of the influential Zia family and the son of…

Continue Reading