LUBBOCK – Only three non-conference games remain for No. 16 Texas Tech with two coming this week – first against Northern Colorado at 7 p.m. on Tuesday at United Supermarkets Arena and then a marquee matchup against No. 3 Duke on Saturday at…

Author: admin

-

Belfast’s Your Roots Are Showing music conference confirms global speakers & and panelists | Media

Your Roots Are Showing – Ireland’s international folk, roots and traditional music conference – is promising its “most ambitious and authoritative programme to date” ahead of its arrival at the ICC in Belfast from…

Continue Reading

-

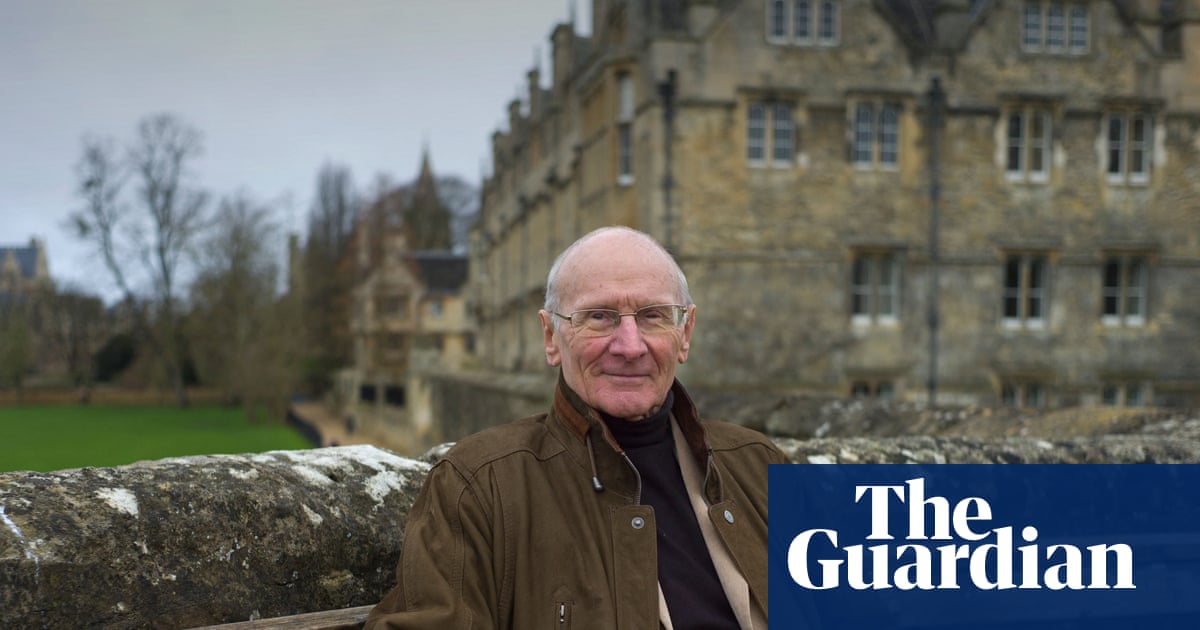

John Carey obituary | Books

John Carey, who has died aged 91, bestrode the ever-narrowing bridge that connects the academic teaching of English literature to the world of literary journalism like a colossus. An Oxford don for more than 40 years – 25 of them as Merton…

Continue Reading

-

Export-led economy key to national development: Nazir Hussain – RADIO PAKISTAN

- Export-led economy key to national development: Nazir Hussain RADIO PAKISTAN

- The South belt’s potential for manufacturing Dawn

- Export-led growth ensures speedy economic development: Saif Associated Press of Pakistan

- Govt focusing on private…

Continue Reading

-

The Canon camera that let you see everything and split the photography world In half!

For professional sports photographers (and a very few others) one of the big bugaboos with Single Lens Reflex cameras is the loss of the image during the precise moment that the photo is captured.

The Instant Return mirror (first used in the 1954…

Continue Reading

-

Stockton gymnastic studio revamp to benefit more students

Enovert Community Trust

Enovert Community TrustGymMad say more students can now use the facility to train Owners of a gymnastics academy say they can now welcome hundreds more students thanks to a £45,000 refurbishment of its training facility.

GymMad Gymnastics Academy…

Continue Reading

-

Brown University Shooting Live Updates: Active Shooter Alert Issued – The New York Times

- Brown University Shooting Live Updates: Active Shooter Alert Issued The New York Times

- Photos show police investigation of a shooting at Brown University. AP News

- Police hunt for gunman who killed 2 Brown University students, injured 9 people in…

Continue Reading

-

NETMARBLE REVEALS NEW TRAILER FOR THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS: ORIGIN AT THE GAME AWARDS 2025

Set in the Vast Open World

LOS ANGELES – DECEMBER 12, 2025 – Netmarble, a leading developer and publisher of high-quality games, revealed a new trailer for its upcoming open-world action RPG The Seven Deadly Sins: Origin at The Game…Continue Reading

-

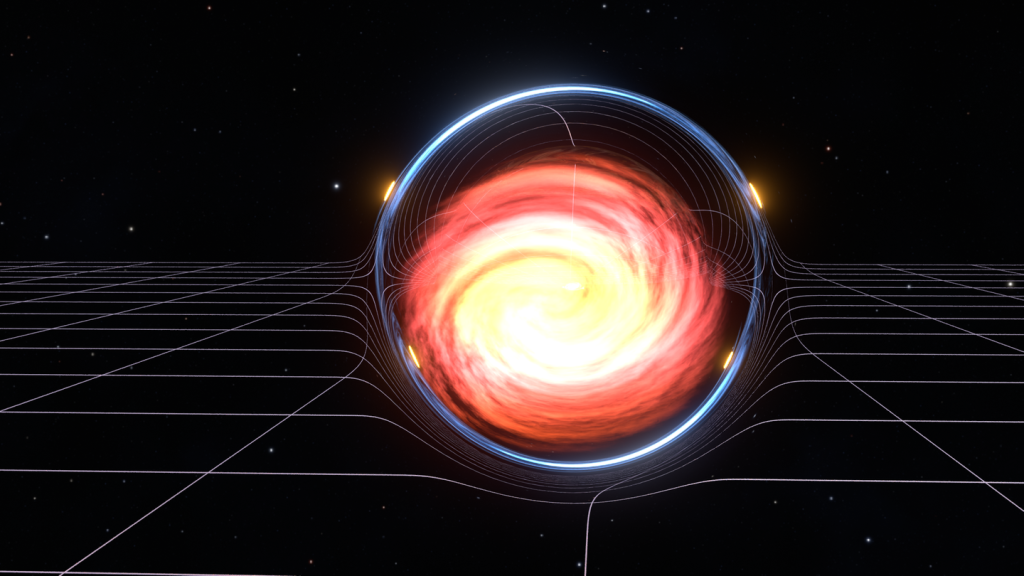

Keck Observatory observes first gravitationally lensed superluminous supernova : Maui Now

An artist’s interpretation of light from a supernova passing through a gravitational lens,

reaching Earth at different times. Credit: Oskar Klein Center, University of Stockholm /

Samuel Avraham & Joel Johansson.An international team of…

Continue Reading