In the future, some of us will be wearing clothes made of bacteria that change colors based on the level of radiation we’re exposed to. At least, that’s the hope of scientists and a fashion designer in Scotland.

Too much ionizing radiation…

In the future, some of us will be wearing clothes made of bacteria that change colors based on the level of radiation we’re exposed to. At least, that’s the hope of scientists and a fashion designer in Scotland.

Too much ionizing radiation…

This article is an on-site version of our Swamp Notes newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Monday and Friday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Does…

LONDON: The Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Science at King’s College London has announced the success of multiple…

HIV drug resistance is common across sub-Saharan Africa, with new population-level data showing that more than one in three people on antiretroviral therapy (ART) carried at least one resistance-associated mutation between 2015 and 2019,…

News of Netflix’s bid to buy Warner Bros. last week sent shock waves through the media ecosystem.

The pending US$83 billion deal is being described as an upending of the existing entertainment order, a sign that it’s now dominated by…

Imagine you got a rough night of sleep. Perhaps you went to bed too late, needed to wake up early or still felt tired when you woke up from what should have been a full night’s sleep.

For the rest of the day, you feel groggy and…

The amount of electricity data centers use in the U.S. in the coming years is expected to be significant. But regular reports of proposals for new ones and cancellations of planned ones mean that it’s difficult to know exactly how many data centers will actually be built and how much electricity might be required to run them.

As a researcher of energy policy who has studied the cost challenges associated with new utility infrastructure, I know that uncertainty comes with a cost. In the electricity sector, it is the challenge of state utility regulators to decide who pays what shares of the costs associated with generating and serving these types of operations, sometimes broadly called “large load centers.”

States are exploring different approaches, each with strengths, weaknesses and potential drawbacks.

For years, large electricity customers such as textile mills and refineries have used enough electricity to power a small city.

Moreover, their construction timelines were more aligned with the development time of new electricity infrastructure. If a company wanted to build a new textile mill and the utility needed to build a new gas-fired power plant to serve it, the construction on both could start around the same time. Both could be ready in two and a half to three years, and the textile mill could start paying for the costs necessary to serve it.

Modern data centers use a similar amount of electricity but can be built in nine to 12 months. To meet that projected demand, construction of a new gas-fired power plant, or a solar farm with battery storage, must begin a year – maybe two – before the data center breaks ground.

During the time spent building the electrical supply, computing technology advances, including both the capabilities and the efficiency of the kinds of calculations artificial intelligence systems require. Both factors affect how much electricity a data center will use once it is built.

Technological, logistical and planning changes mean there is a lot of uncertainty about how much electricity a data center will ultimately use. So it’s very hard for a utility company to know how much generating capacity to start building.

This uncertainty costs money: A power plant could be built in advance, only to find out that some or all of its capacity isn’t needed. Or no power plant is built, and a data center pops up, competing for a limited supply of electricity.

Either way, someone needs to pay – for the excess capacity or for the increased price of what power is available. There are three possible groups that might pay: the utilities that provide electricity, the data center customers, and the rest of the customers on the system.

However, utility companies have largely ensured their risk is minimal. Under most state utility-regulation processes, state officials review spending proposals from utility companies to determine what expenses can be passed on to customers. That includes operating expenses such as salaries and fuel costs, as well as capital investments, such as new power plants and other equipment.

Regulators typically examine whether proposed expenses are useful for providing service to customers and reasonable for the utility to expect to incur. Utilities have been very careful to provide their regulators with evidence about the costs and effects of proposed data centers to justify passing the costs of proposed investments in new power plants along to whomever the customers happen to be.

Regulators, then, are left to equitably allocate the costs to the prospective data center customers and the rest of the ratepayers, including homes and businesses. In different states, this is playing out differently.

Kentucky is attempting to address the demand uncertainty by conditionally approving two new natural gas-fired generators in the state. However, the utility companies – Louisville Gas & Electric and Kentucky Utilities – must demonstrate that those plants will actually be needed and used. But it’s not clear how they could do that, especially considering the time frames involved.

For instance, suppose the utility has a letter of agreement or even a contract with a new data center or other large customer. That might be sufficient proof for the regulator to approve charging customers for the costs of building a new power plant.

But it’s not clear what would happen if the data center ends up not being built, or needing much less power than expected. If the utility can’t get the money from the data center company – because they bill customers based on actual usage – that leaves regular consumers on the hook.

In Ohio, the major power company AEP has a specific rate plan for data centers and other large electricity customers. One element, called a “demand ratchet,” is designed to mitigate month-to-month uncertainty in electricity consumption by data centers. The data center’s monthly bill is based on the current month’s demand or 85% of the highest monthly demand from the previous 11 months – whichever is higher.

The benefit is that it protects against a data center using huge amounts of electricity one month and very little the next, which would otherwise yield a much lower bill. The ratchet helps ensure that the data center is paying a significant share of the cost of providing enough electricity, even if it doesn’t use as much as was expected.

This ratchet effectively locks in the data center’s payments for 12 months, but regulators might expect a longer commitment from the center. For instance, Florida’s utilities regulator has approved an agreement that would require a data center company to pay for 70% of the agreed-upon demand in their entire electricity contract, even if the company didn’t use the power.

Another aspect of Ohio’s approach addresses the risk of changing business plans or technology. AEP requires a credit guarantee, like a deposit, letter of credit or parent company guarantee of payment, equal to 50% of the customer’s expected minimum bill under the contract. While this theoretically reduces the risk borne by other customers, it also raises concerns.

For example, a utility may not end up signing contracts directly with a large, well-known, wealthy technology company but with a subsidiary corporation with a more generic name – imagine something like “Westside Data Center LLC” – created solely to build and operate one data center. If the data center’s plans or technology changes, that subsidiary could declare bankruptcy, leaving the other customers with the remaining costs.

A key advantage to these new types of customers is that they are extremely nimble in the way they use electricity.

If data centers can make money based on their flexibility, as they have in Texas, then a portion of those profits can be returned to the other customers that shared the investment risk. A similar mechanism is being implemented in Missouri: If the utility makes extra money from large customers, then 65% of that revenue increase is returned to the other customers.

Change is coming to the U.S. electricity system, but nobody is sure how much. The methods by which states are trying to allocate the cost of that uncertainty vary, but the critical element is understanding their respective strengths and weaknesses to craft a system that is fair for everyone.

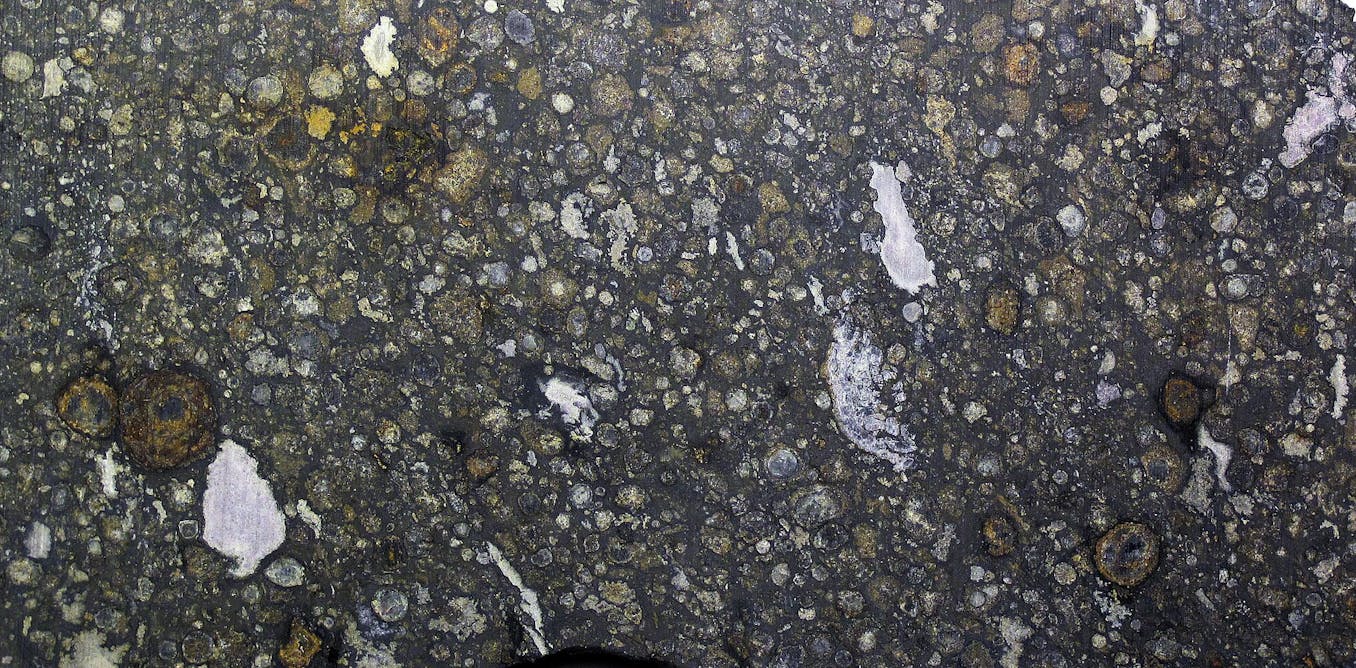

When NASA scientists opened the sample return canister from the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample mission in late 2023, they found something astonishing.

Dust and rock collected from the asteroid Bennu contained many of life’s building blocks,…

Maria Balshaw is to step down as the director of Tate in 2026, after a challenging nine-year tenure when she steered the organisation through the Covid-19 pandemic and had to deal with fluctuating attendance figures and financial instability.