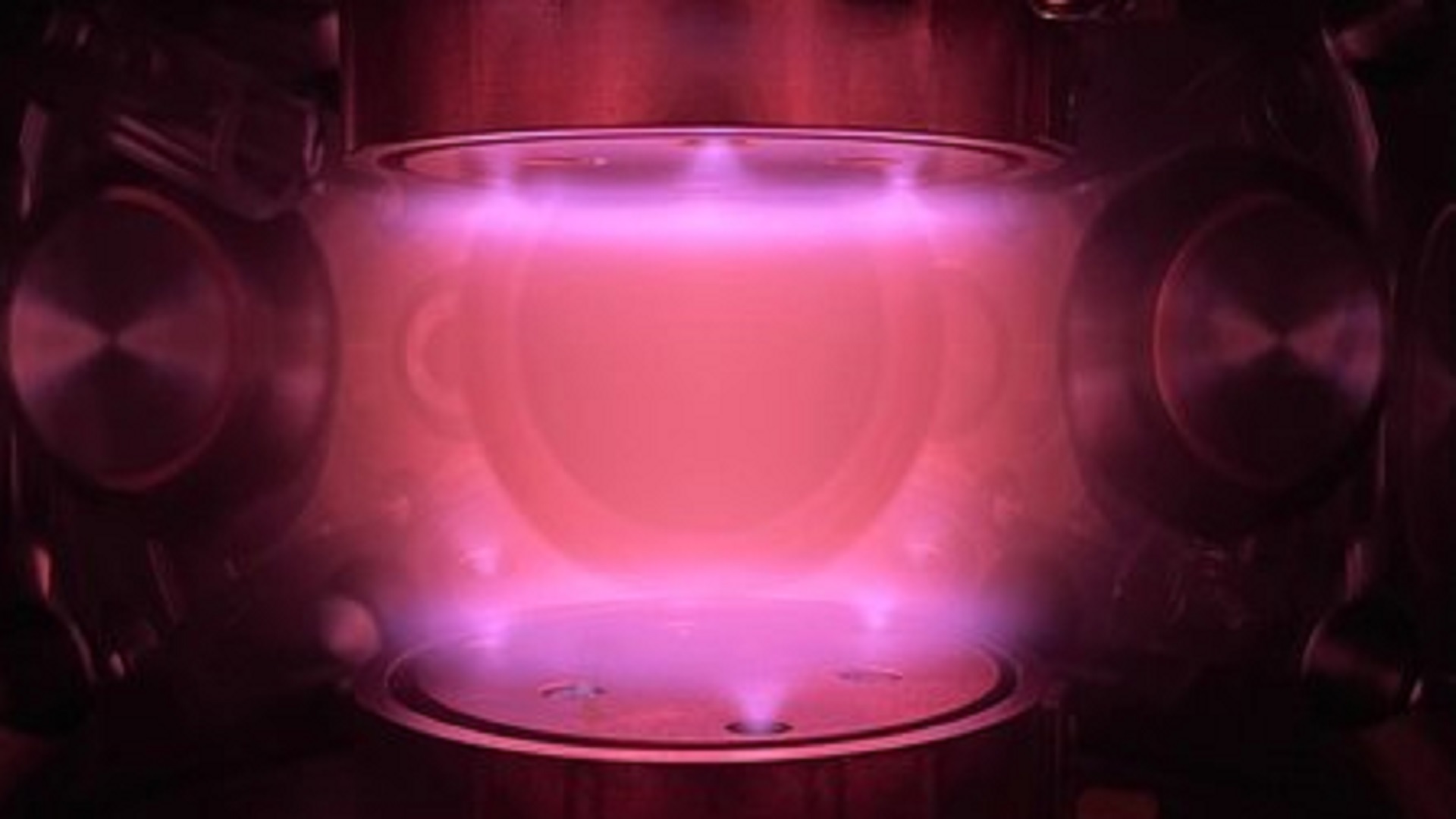

Researchers in the US have just discovered a new behavior in plasmas after recreating the bizarre conditions seen in deep space, where icy dust, electrified gas, and freezing temperatures collide.

In the lab, the team of scientists at the…

Researchers in the US have just discovered a new behavior in plasmas after recreating the bizarre conditions seen in deep space, where icy dust, electrified gas, and freezing temperatures collide.

In the lab, the team of scientists at the…

Paramount and Netflix are in a vicious tug-of-war over Warner Bros. Discovery.

On one side of the rope: the suitor WBD’s board signed off on, Netflix, which announced a $72 billion deal last week. On the other side, the suitor the board turned down, Paramount, which is resorting to a tactic known as a hostile takeover.

A hostile takeover occurs when a company attempts to acquire another by going around the takeover target’s management and making an appeal directly to shareholders.

While friendly, mutually agreed upon acquisitions between two companies tend to have a higher success rate, hostile takeover bids, though riskier and often costly, can prove successful, too.

If Paramount’s $30-per-share, all-cash bid worth $108 billion (including debt) for complete ownership of WBD succeeds, it’ll be the fourth-largest hostile takeover to be completed over the past 20 years, according to data Dealogic shared with CNN. And oftentimes the initial hostile takeover bid a company announces goes even higher.

As it stands, though, here are the top five largest hostile takeover bids that have succeeded. All figures exclude debt:

In 1999, UK-based telecom company Vodafone Airtouch (now Vodafone Group) first presented the board of German telecom company Mannesmann with an all-stock acquisition, which Mannesmann’s board rejected.

Vodafone proceeded with a hostile takeover bid to buy Mannesmann shares that was finalized in 2000 and valued at $171 billion.

Anheuser-Busch, the victim of a successful hostile takeover bid by InBev, formed a company that later became known as Anheuser-Busch InBev. That company then launched a hostile takeover bid for SABMiller in 2015 after it failed repeatedly at friendly takeover attempts. The negotiated deal settled at $122 billion in 2016.

Pfizer succeeded with its hostile takeover bid of Warner-Lambert, a pharmaceutical company known for making the cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor, in 2000. The all-stock deal closed at $110 billion that year.

Royal Bank of Scotland, seeking to prevent a friendly takeover of Dutch bank ABN Amro by Barclays, got two other banks to collectively make a hostile bid that would divide ABM among all three. It was eventually finalized in 2007 in a deal valued at $96 billion. The deal, however, helped contribute to RBS’ demise.

Sanofi-Synthelabo’s surprise hostile takeover bid of Aventis, a Franco-German pharmaceutical company, was valued at $73 billion in 2004.

The Women’s Tennis Association has announced a long-term partnership with Mercedes-Benz which has the potential to be the largest in women’s sport.

The German car manufacturer will become the premier partner of the WTA and pour $50m (£37.5m) per…

The Association predicts the winners of Wednesday’s Western Conference quarterfinals in the Emirates NBA Cup 2025.

The NBA season is two months complete and approaching the Christmas checkpoint, which means few, if any, conclusions can be…

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major global health concern characterized by high incidence and mortality rates, imposing heavy burdens on patients and healthcare systems alike.1,2 Over 800,000 cases are reported annually…

Max Verstappen has paid tribute to long-time race engineer Gianpiero Lambiase following the close of the 2025 season, with the Dutchman feeling “very proud” to work with his colleague after what he called an “emotional year”.

Lambiase –…

PARIS — Thieves who stole more than $100 million in crown jewels from the Louvre in October escaped with barely 30 seconds to spare, a French Senate inquiry said Wednesday, as lawmakers detailed a cascade of security failures that allowed…

Question: One of the most important competitive aspects of any NTT INDYCAR SERIES season is the pairing of a driver with a strategist. Given that several teams have announced new pairings for 2026, which one – old or new –…

Pakistan and the United Kingdom on Wednesday formalised a major cooperation agreement aimed at accelerating joint action against climate change, with both sides calling the partnership urgent, modern, and essential…

CrowdStrike embraces MITRE’s first real-world cross-domain attack simulation, delivering perfect scores with no false positives

AUSTIN, Texas – December 10, 2025 – CrowdStrike (NASDAQ: CRWD) delivered 100% detection and 100% protection with no false positives in the 2025 MITRE ATT&CK® Enterprise Evaluations – the most technically demanding in the program’s history. Through MITRE’s first-ever cloud adversary emulation with attacks that moved across identity, endpoint, and cloud, the unified Falcon® platform demonstrated the architectural advantage required to stop modern cross-domain threats.

“These were the most challenging MITRE evaluations yet, and we participated to give the industry a transparent view into which platforms have the architecture to stop real-world threats,” said Michael Sentonas, president of CrowdStrike. “Delivering 100% detection, 100% protection, and no false positives across these highly sophisticated, cross-domain attacks is a major achievement. The results show the power of the unified Falcon platform – complete protection with a first-class analyst experience that eliminates noise and complexity while accelerating response.”

Testing Unified Platform Capabilities Against Real-World, Cross-Domain Attacks

This year’s MITRE evaluations expanded beyond endpoint techniques to assess true platform capabilities in defending against real-world attacks that move across identity, endpoint, and cloud. As the leading unified security platform participating in this year’s evaluations, CrowdStrike achieved 100% detection and 100% protection with no false positives across the full attack sequence.

In the most demanding evaluations to date, MITRE exercised full cross-domain tradecraft, effectively testing the strength of the underlying platform architecture – not just its detections. To execute this expanded scope, MITRE emulated real-world attacks from Chinese state-sponsored espionage group MUSTANG PANDA, and eCrime group SCATTERED SPIDER – two adversaries known for their sophistication, stealth, and ability to compromise cloud environments. It also introduced new early-stage techniques to assess whether a platform can detect and contain activity before attackers can establish a foothold or move laterally.

The Falcon platform delivered complete detection and protection at every stage, stopping credential abuse, lateral movement, and cloud exploitation exactly as exercised in MITRE’s scenarios – demonstrating the power of a single, unified platform to stop modern cross-domain attacks.

Additional Resources

About CrowdStrike

CrowdStrike (NASDAQ: CRWD), a global cybersecurity leader, has redefined modern security with the world’s most advanced cloud-native platform for protecting critical areas of enterprise risk – endpoints and cloud workloads, identity and data.

Powered by the CrowdStrike Security Cloud and world-class AI, the CrowdStrike Falcon® platform leverages real-time indicators of attack, threat intelligence, evolving adversary tradecraft and enriched telemetry from across the enterprise to deliver hyper-accurate detections, automated protection and remediation, elite threat hunting and prioritized observability of vulnerabilities.

Purpose-built in the cloud with a single lightweight-agent architecture, the Falcon platform delivers rapid and scalable deployment, superior protection and performance, reduced complexity and immediate time-to-value.

CrowdStrike: We stop breaches.

Learn more: https://www.crowdstrike.com/

Follow us: Blog | X | LinkedIn | Instagram

Start a free trial today: https://www.crowdstrike.com/trial

© 2025 CrowdStrike, Inc. All rights reserved. CrowdStrike and CrowdStrike Falcon are marks owned by CrowdStrike, Inc. and are registered in the United States and other countries. CrowdStrike owns other trademarks and service marks and may use the brands of third parties to identify their products and services.

Media Contact

Jake Schuster

CrowdStrike Corporate Communications

press@crowdstrike.com