…

Author: admin

-

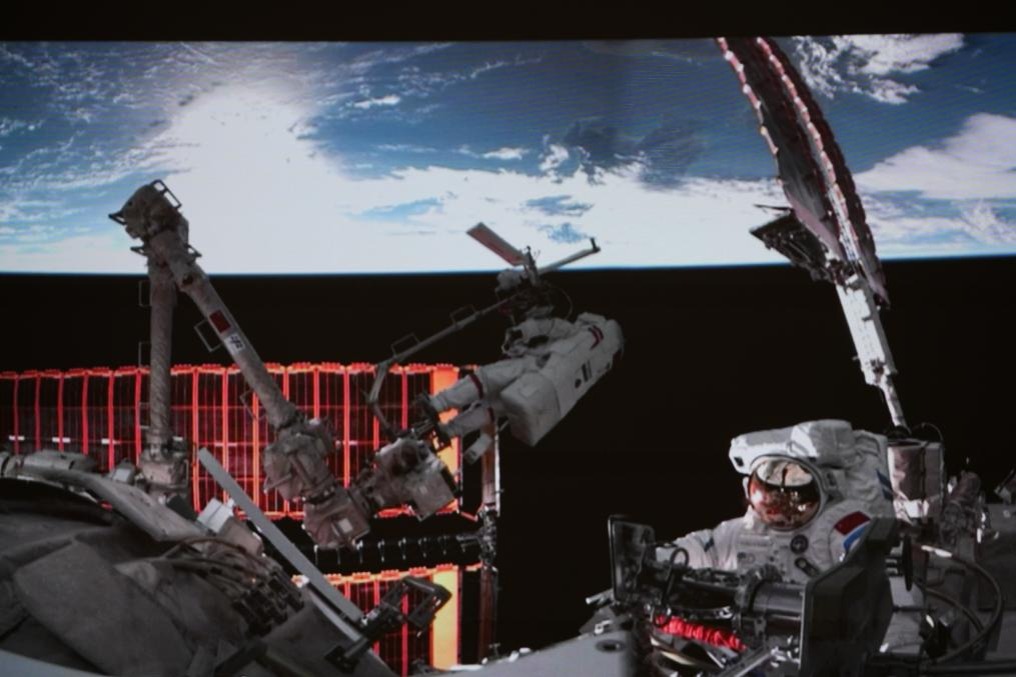

New spacesuits debuted for Shenzhou XXI’s first spacewalk

This screen image captured at Beijing Aerospace Control Center on Dec 9, 2025 shows Shenzhou XXI astronauts performing extravehicular activities outside China”s orbiting space station. [Photo/Xinhua]

-

Pat Cummins returns at the helm as Australia announce their squad for the Adelaide Test

Australia have announced their 15-member squad for the third Test of the ongoing Ashes, to be played at Adelaide. Pat Cummins is set to walk back as captain and spearhead after months on the sidelines. The hosts already hold a commanding 2-0…

Continue Reading

-

From patriots to traitors – Dawn

- From patriots to traitors Dawn

- Video: Pak Army Spokesman Winks At Woman Reporter During Presser, Faces Backlash NDTV

- Point of no return? The Express Tribune

- Who is Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry, the Pakistan Army spokesperson criticised for winking at…

Continue Reading

-

MI Emirates’ dramatically collapse to hand Vipers victory

Earlier, in the chase Jonny Bairstow holed out to deep backward square-leg immediately after flicking Tanveer in the same region for six. Muhammad Waseem and Tom Banton hit Payne for three fours together while they hit two more boundaries off Sam…

Continue Reading

-

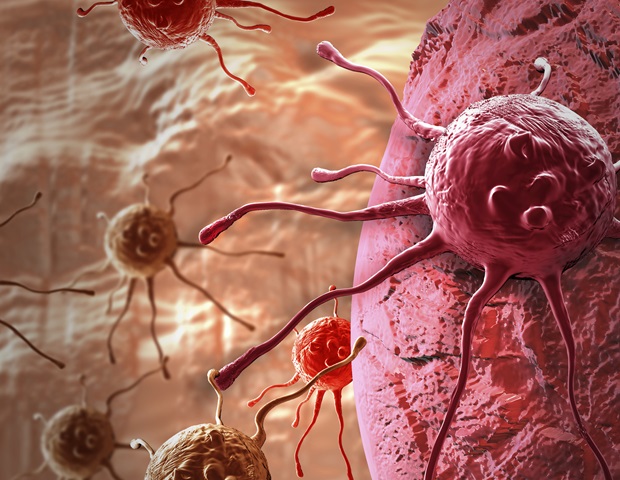

AI-driven method uncovers genetic interactions that fuel cancer progression

University of South Australia scientists have developed a powerful new way to uncover the genetic interactions that fuel cancer progression, paving the way for earlier and more precise treatments.

The AI-driven method, published…

Continue Reading

-

Russian bombers join Chinese air patrol near Japan as Tokyo-Beijing tie strains – Reuters

- Russian bombers join Chinese air patrol near Japan as Tokyo-Beijing tie strains Reuters

- S Korea, Japan scramble warplanes in response to Russia, China air patrol Al Jazeera

- South Korean fighters scramble to meet Russian, Chinese aircraft on…

Continue Reading

-

Sedative choice could improve outcomes for breathing tube patients

Doctors treating seriously ill patients in an emergency setting may want to give the sedative etomidate, rather than ketamine, while placing a breathing tube, according to a randomized trial published in the New England Journal of…

Continue Reading

-

China adds domestic AI chips to official procurement list for first time

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

China has put domestic artificial intelligence chips on an official procurement list for the first time, bolstering the nation’s tech sector ahead of US President Donald Trump’s move to allow Nvidia exports to the country.

The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology recently added AI processors from Chinese groups including Huawei and Cambricon to its government-approved list of suppliers, according to two people familiar with the matter.

The step was designed to enhance the use of domestic semiconductors in China’s public sector and could be worth billions of dollars in new sales to local chipmakers.

That move came before Trump announced on Monday he was lifting US export controls and allowing Nvidia to ship its advanced H200 chips to “approved customers in China”. However, those sales could still be hampered by opposition from some Washington lawmakers and Chinese authorities.

China’s new procurement list has not yet been made public, but several government agencies and state-owned companies have already received the guidance document, said those familiar with the matter. While they have previously been urged to support local chipmakers, it is the first time public sector groups have received written instructions.

The move is a sign of Beijing’s determination to wean the country from relying on American technology and bolster its homegrown semiconductor industry in the AI race against the US.

The Information Technology Innovation List — known as Xinchuang in Chinese — serves as guidelines for government agencies, public institutions and state-owned companies that spend billions every year procuring IT products.

The list forms part of Beijing’s strategy to reduce China’s reliance on foreign products following Washington’s export controls.

Domestic microprocessors to replace those made by AMD and Intel, as well as operating systems to substitute Microsoft’s Windows, have been added to the list in the past few years.

This has led to the gradual phasing out of foreign technology products in China’s public institutions such as government offices, schools and hospitals, as well as state-owned companies.

The move also shows confidence that domestic AI chips have reached a performance level to replace their US counterparts, following a concerted push by Beijing to focus resources on the sector over the past few years.

China recently increased subsidies that cut energy bills by up to half for some of the country’s largest data centres, in a bid to help tech giants such as Alibaba and Tencent with the higher electricity costs of using less efficient domestic semiconductors.

The push to replace Nvidia’s technology with domestic counterparts has faced some resistance from companies.

An executive from a state-owned financial institute said that while they have allocated Rmb100mn ($14mn) to buy domestic AI chips from the list this year, most of these purchased Chinese processors the group has acquired are now sitting idle.

His firm’s quantitative trading models were built based on Nvidia’s hardware, and a switch to Huawei’s processors will result in a significant amount of adaptation work, including rewriting code in a language they are not familiar with.

Such reluctance to shift to a new architecture is common in a transition phase, according to one Chinese policymaker, who added that the country needed to gain greater technological independence. “The growing pains are unavoidable,” they said. “But we have to get there.”

The MIIT did not respond to requests for comment.

Additional reporting from Cheng Leng and Ryan McMorrow in Beijing

Continue Reading

-

Punjab urged to focus on data for HIV prevention – Dawn

- Punjab urged to focus on data for HIV prevention Dawn

- Aids spreading fast in Khyber, warn health experts Dawn

- Event held to create awareness about HIV, allied diseases The Nation (Pakistan )

- Pakistan sees 200% surge in HIV cases; WHO warns of…

Continue Reading

-

ECP hears KP CM code of conduct case today – Dawn

- ECP hears KP CM code of conduct case today Dawn

- Negotiations underway as PTI sit-in continues outside Adiala jail The Express Tribune

- CM hands over bulletproof vehicles, modern weapons to police Dawn

- Centre, not KP govt, responsible for security…

Continue Reading