Following the release of the 590 driver branch, which formally ended “Game Ready” support for the GTX 900 and 10 series GPUs, Nvidia has been forced to issue a correction regarding its supported hardware list….

Author: admin

-

“Chainsaw Man”: A Blood-Drenched Antihero for Today

Fujimoto Tatsuki’s Chainsaw Man is one of the biggest manga hits of recent years, with tens of millions of books in print and adaptations for TV and the cinema. A look at what makes this work resonate with modern audiences in Japan and…

Continue Reading

-

Xbox flops on Black Friday

Black Friday has just wrapped up, and we now have a look at the top three best-selling consoles in the US, thanks to Circana. There is a bit of a surprise here, and it manages to beat out both PlayStation and Xbox Series hardware. The NEX…

Continue Reading

-

Constipation is not the first sign of fibre deficiency, it is… | Health News

From weight management to supporting bowel movement and digestion, fibre does it all. But did you know that constipation is not the very first sign of a lack of fibre within the body? According to Dr Leena Saju, Group Manager, Clinical Nutrition,…

Continue Reading

-

Fillon Maillet Last Standing Perfection Seals Oestersund Pursuit Victory

France’s Quentin Fillon Maillet’s penalties in each of the two prone stages dropped him to 10th before the standing stages. The 2022 double Olympic Champion then proceeded to clean the first standing and the crucial last standing, as his…

Continue Reading

-

Cosmetic fillers can cause deadly complication, experts warn — but new tech exposes it

Each year, more than 5 million cosmetic filler procedures are performed in the U.S. — but these injectables can potentially block key blood vessels, putting patients at risk for serious harm.

In a study presented this week at the annual meeting…

Continue Reading

-

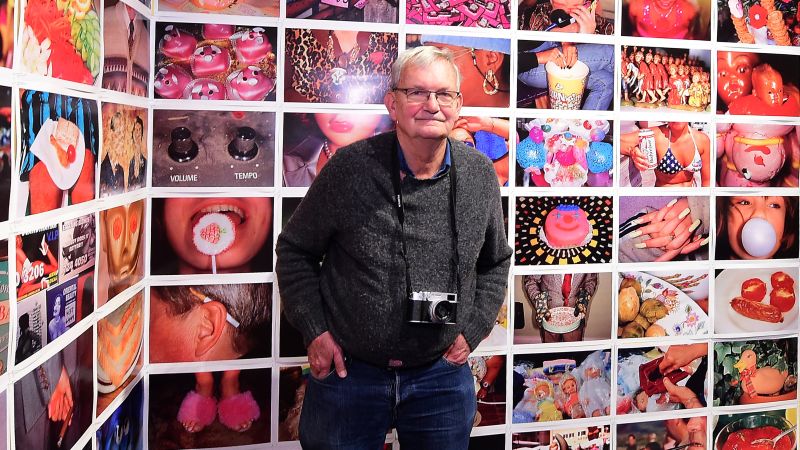

Martin Parr: British documentary photographer dies at 73

One of Britain’s most acclaimed photographers, Martin Parr, died on Saturday at age 73, his foundation said on Sunday.

A prolific photographer and collector, Parr obsessively documented…

Continue Reading

-

50 children dead in Somalia amid diphtheria outbreak-Xinhua

MOGADISHU, Dec. 7 (Xinhua) — Somalia’s Ministry of Health and Human Services on Sunday confirmed that a new diphtheria outbreak has killed 50 children and infected about 1,000 others nationwide.

In a statement, the ministry said children…

Continue Reading

-

50 children dead in Somalia amid diphtheria outbreak-Xinhua

MOGADISHU, Dec. 7 (Xinhua) — Somalia’s Ministry of Health and Human Services on Sunday confirmed that a new diphtheria outbreak has killed 50 children and infected about 1,000 others nationwide.

In a statement, the ministry said children…

Continue Reading

-

OH Oscar Piastri’s Standout F1 Season

At Haileybury, we are filled with immense pride as we celebrate the extraordinary achievements of one of our own – Oscar Piastri (Kipling, 2020).

As a Formula One racing driver, Oscar has not only reached the…

Continue Reading