Juventus FC/Getty Images

Juventus FC/Getty Images“He’s officially the top dog, isn’t he,” former Man City defender Micah Richards…

Juventus FC/Getty Images

Juventus FC/Getty Images“He’s officially the top dog, isn’t he,” former Man City defender Micah Richards…

Ranveer Singh’s high-octane spy thriller ‘Dhurandhar’, directed by Aditya Dhar, is off to a powerful start at the box office, showing good growth and impressive momentum as it powers through its debut weekend.Dhurandhar Movie ReviewAfter…

Economic growth in the EU has been persistently slower than in the US over the past two decades. Economic growth has been slowing, mainly due to weakening labour productivity growth according to the Draghi Report (Draghi 2024). While much of the debate has focused on investment gaps, regulatory barriers, and labour market dynamics at the national level, less attention has been paid to the role of economic structure at a fine geographical scale in shaping Europe’s diverging growth trajectories.

Our recent analysis (Dijkstra et al. 2025) aims to fill this gap by building on previous studies (Enflo 2010, Le Gallo and Kamarianakis 2011, Gómez-Tello et al. 2020, Kilroy and Gana 2020, Martin et al. 2018) and using novel data from the Annual Regional Database of the European Commission (ARDECO). Armed with these data, we examine for the first time productivity dynamics across metropolitan regions (‘metros’) in Europe over the period 2001–2021 with a ten-sector disaggregation analysis.

The results reveal a nuanced geography of economic growth. In capitals, growth was fuelled by both productivity growth and employment growth, which may explain why they also saw the highest population growth (Table 1). In other metropolitan areas, however, employment, productivity, and populations grew at half the rate of capitals. In the rest of the EU (i.e. non-metros), populations shrank and employment barely grew, but labour productivity grew almost as fast as in capitals.

Table 1 Decomposing the growth of gross value added (GVA) per capita in EU capitals, other metros, and non-metro regions, 2001-2021

When we look at the drivers of productivity growth, one pattern stands out: productivity growth occurred mostly within economic sectors rather than through shifts to more productive sectors in all three types of regions, although its relative importance varied. Capitals experienced high productivity growth, but employment growth was higher in less productive sectors, suggesting that the concentration of highly productive sectors – such as finance and professional services – generates more demand for employment in other sectors, such as retail, arts, and sports (Moretti 2012). Other metros and non-metros also achieved part of their growth through higher employment growth in more productive sectors, reflecting the fact that structural transformations are still ongoing.

Changes in employment by sector confirm this. Between 2001 and 2021, capital regions expanded their employment shares in services (e.g. information and communication services, professional services), while employment in industry, and trade, transport, and hotels declined (Figure 1). Other metropolitan regions followed a similar but less pronounced trajectory. In contrast, non-metropolitan regions remained more dependent on traditional sectors and experienced limited employment growth. This implies that the shift of employment happened through reductions in employment in industry and agriculture rather than through labour expansion.

Figure 1 Employment per sector by type of region in the EU in 2001, 2011, and 2021

Productivity growth over the period 2001-2021 was fuelled by:

Figure 2 Labour productivity growth in capitals and other metros, 2001-2021

Our findings suggest that productivity at the local level is more nuanced than simply “cities are good and other places are lagging”. The findings contribute to the growing debate on agglomeration economies and labour productivity inequalities. Specifically, our work underscores the need to assess why other metro regions have underperformed over the past two decades, and whether non-metro regions will continue to converge or whether their growth will stall once they have transitioned to more productive sectors.

Innovation can increase regional productivity, as shown in our regression analysis and the literature. This analysis is relevant for regional development policy, especially in the context of the debate on EU cohesion policy in the next programming period. Our study highlights the different trends in productivity growth and sectoral composition of capitals, other metros and non-metros. This suggests that a tailored approach to address the distinct challenges and opportunities of different regional contexts may be more successful. Furthermore, the findings can help to identify strategies that enhance European competitiveness by embracing regional specificities (Capello and Rodríguez-Pose 2025).

Capello, R and A Rodríguez-Pose (2025), “Europe’s quest for global economic relevance: On the productivity paradox and the Draghi report”, Scienze Regionali 24(1): 7-15.

Dijkstra, L, M Kompil and P Proietti (2025), “Are cities the real engines of growth in the EU?”, Geography and Environment Discussion Paper No. 2025, LSE.

Draghi, M (2024), The future of European competitiveness, European Commission.

Enflo, K S (2010), “Productivity and employment—Is there a trade-off? Comparing Western European regions and American states 1950–2000”, The Annals of Regional Science 45(2): 401-421.

Gómez‐Tello, A, M J Murgui‐García and M T Sanchis‐Llopis (2020), “Exploring the recent upsurge in productivity disparities among European regions”, Growth and Change 51(4): 1491-1516.

Kilroy, A and R Ganau (2020), “Economic growth in European Union NUTS-3 regions”, Finance, Competitiveness and Innovation Global Practice, World Bank.

Le Gallo, J and Y Kamarianakis (2011), “The evolution of regional productivity disparities in the European Union from 1975 to 2002: A combination of shift–share and spatial econometrics”, Regional Studies 45(1): 123-139.

Martin, R, P Sunley, B Gardiner, E Evenhuis and P Tyler (2018), “The city dimension of the productivity growth puzzle: the relative role of structural change and within-sector slowdown”, Journal of Economic Geography 18(3): 539-570.

Moretti, E (2012), The New Geography of Jobs, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

A feature that we’ve taken for granted since 2020 – the ability to shoot Portrait Mode photos using Night Mode – has quietly vanished from the latest Pro models. Users started noticing something was wrong and flagged it on Reddit and

The boys are back in town, one last time.

The first trailer for The Boys arrived Saturday at CCXP in São Paulo — and things look more dire than ever for Billy Butcher and his crew, who after the events of the season four finale, are…

Five games, five wins and a place in the quarter-finals: Norway’s experience at the 2025 IHF Women’s World Championship has been perfect so far.

So perfect in fact that with two of their three games remaining in the main round, Norway had…

8.30pm, BBC One

There’s a huge job for the Doctor’s occasional employer Unit in this ambitious sci-fi spin-off from Russell T Davies. A fearsome species (the Sea Devils – last seen during Jodie…

The original version of this story appeared in Quanta Magazine.

Here’s a test for infants: Show them a glass of water on a desk. Hide it behind a wooden board. Now move the board toward the glass. If the board keeps going past the glass, as if…

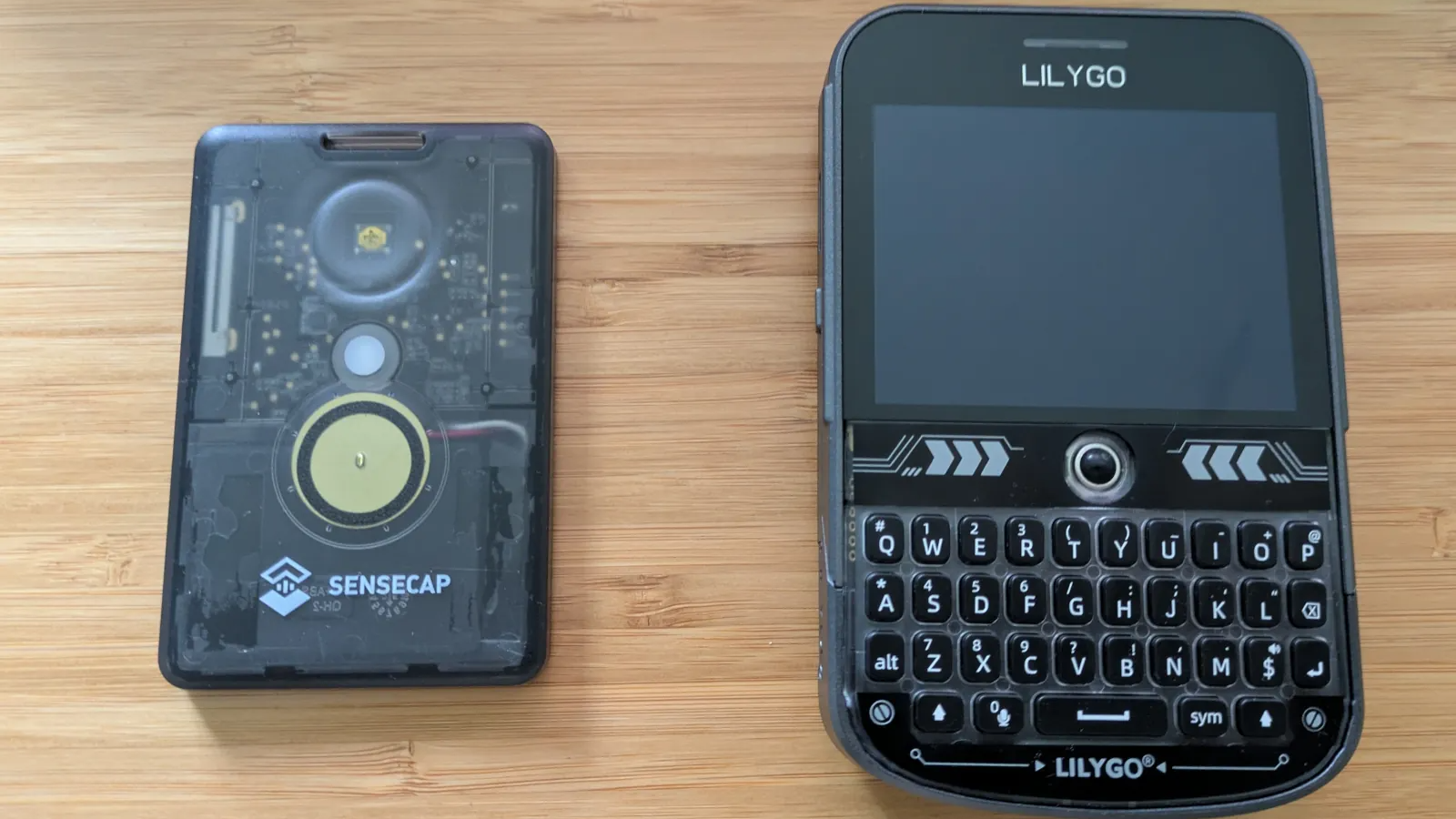

[Michael Lynch] recently decided to delve into the world of off-grid, decentralized communications with MeshCore, because being able to communicate wirelessly with others in a way that does not depend on traditional communication…

The presence of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) at end of treatment (EOT) was shown to be prognostic of event-free survival (EFS) outcomes for patients with lymphoma regardless of subtype, according to findings from a retrospective, real-world analysis presented at the

Findings showed that the median EFS was not achieved (NA) in the ctDNA minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative group (n = 49) vs 1.97 months in the ctDNA-MRD-positive group (n = 19; adjusted HR, 22.43; 95% CI, 6.76-74.45; P < .0001). The 12- and 24-month HRs in the ctDNA-MRD-negative population were 0.83 (95% CI, 0.71-0.98) and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.64-0.96), respectively. The respective HRs in the ctDNA-MRD-positive population were 0.05 (95% CI, 0.01-0.35) and 0.00 (95% CI, NA-NA), respectively.

“EOT ctDNA status can clarify ambiguous imaging results and enables earlier relapse detection,” Natalie Galanina, MD, lead study author and clinician investigator at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, stated in during the presentation. “ctDNA kinetics offer real-time insights into treatment response during first-line therapy and can further predict response to CAR T-cell treatment,” she added.

Personalized, tumor-informed ctDNA assays have shown the ability to capture prognostic and predictive information in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), but its prognostic capability has been understudied in diverse subsets of lymphoma.2

To bridge that gap, investigators prospectively collected real-world data of MRD detection and ctDNA clearance kinetics in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory lymphoma across 14 subtypes.1

“[Signatera is a] personalized tumor-informed assay, where both the tumor and a source of matched normal [tissue] is sequenced, either by whole exome or whole-genome sequencing. Based on the somatic mutation profile of a patient, a custom patient-specific assay is designed to track ctDNA in the plasma. This makes the test ultrasensitive while maintaining extremely high specificity,” Galanina said.

The schema was such that 1105 prospectively collected plasma samples from 144 patients with lymphoma were subject to ctDNA assessment. Samples included aggressive (n = 123) T-cell (n = 13) and B-cell (n = 110) lymphomas, as well as indolent (n = 21) follicular (n = 10), marginal zone (n = 5), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (n = 6).

The demographics of the patient cohort were representative of the real-world population, Galanina said. The median age was 61 years (range, 18-84) and most patients were male (n = 77; 53%). Most patients had stage IV disease (n = 75; 56%), although those with stage I (n = 15; 11%), II (n = 29; 21%), and III (n = 16; 12%) were also included. ECOG performance status was predominantly 0 (n = 50; 46%), followed by 1 (n = 35; 32%), 2 (n = 16; 15%), 3 (n = 6; 5.6%), and 4 (n = 1; 0.9%). Revised International Prognostic Index score fell between 0 and 2 in 25.2% (n = 31) of patients and between 3 and 5 in 26.8% (n = 33) of patients; 80 scores were not reported.

With respect to therapy, patients reported receiving Pola-R-CHP (n = 6; 4.3%), R-CHOP (n = 72; 51%), R-EPOCH (n = 14; 10%), other rituximab (Rituxan; n = 17; 12%), and other (n = 31; 22%).

The median number of ctDNA MRD timepoints was 7 (range, 1-32). Median follow-up for EFS and overall survival (OS) was 20 (range, 1-108) and 21 (range, 1-108) months, respectively.

Pretreatment ctDNA was detectable in 94% of patients with lymphoma. “The median number of tumor molecules per mL was about 100 in aggressive and about 20 in indolent lymphomas, respectively, which may reflect differences in circulating tumor burden,” Galanina stated.

What else was reported on with respect to ctDNA’s validity as a prognostic tool?

Additional data revealed that ctDNA provided a better indication for treatment response than traditional imaging. Patients who had a negative PET-CT at EOT (n = 35) experienced a median EFS that was NA vs 5.16 months in those whose PET-CT was positive at EOT (n = 25; adjusted HR, 8.68; 95% CI, 2.41-31.29; P = .0010). Conversely, patients who had negative ctDNA-MRD at EOT (n = 44) experienced a median EFS that was NA vs 2.04 months in those who had positive ctDNA-MRD at EOT (n = 16; adjusted HR, 49.77; 95% CI, 9.91-250.02; P < .0001).

Furthermore, PET-negative patients with negative ctDNA-MRD (n = 32) had a median EFS that was NA vs 2.76 months in those with positive ctDNA-MRD (n = 3; HR, 45.29; 95% CI, 4.63-443.27; P = .0011). PET-positive patients with negative ctDNA-MRD (n = 12) had a median EFS that was NA vs 1.97 months in those with positive ctDNA-MRD (n = 13; HR, 12.26; 95% CI, 3.23-46.59; P = .0002).

“The clinical significance of this result is that EOD PET-positive patients present a significant clinical challenge, and most of them ultimately proceed to receive additional therapy. However, although the patient numbers are small, our data clearly show that the majority or 75% of PET-positive MRD-negative patients do not progress, and therefore may not require any additional therapy,” Galanina said. “Based on this, it is reasonable to integrate ctDNA as an adjunct to EOT assessment to help further risk stratify patients who are likely to relapse vs those who remain disease free.”

“For patients who are EOD PET negative, if they are ctDNA positive, this may inform post treatment surveillance, as these patients may need to be monitored more closely, and patients who are PET positive, if they’re MRD negative, may be appropriate candidates for observation only, or at the very least require pathologic confirmation of the PET-positive lesions to rule out the non-etiology of the FDG uptake, as those patients have generally good outcomes,” Galanina added.

In multi-variable analysis investigators demonstrated that ctDNA was the most significant predictor of EFS after correcting for all other factors, including age, tumor histology, and stage (P < .001).

ctDNA clearance during frontline therapy was also shown to be prognostic of outcomes in all lymphoma subtypes. The median EFS was NA in patients who cleared their ctDNA (n = 48) vs 2.05 months in those who did not (n = 12; adjusted HR, 8.57; 95% CI, 2.55-28.81; P = .0005). Moreover, the median EFS was NA, NA, and 2.05 months in patients with cycle 1 clearance (n = 14), delayed clearance (n = 34), and no clearance, respectively. The adjusted HRs for patients without clearance vs those with cycle 1 clearance and delayed clearance were 20.95 (95% CI, 2.09-21.11; P = .0097) and 7.45 (95% CI, 2.22-24.98; P = .0011), respectively.

“Early clearance by cycle 1 may have significant implications for potential de-escalation of therapy, especially for older patients and those with comorbidities,” Galanina explained.

“Lastly, we also looked at ctDNA clearance in patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy [and we found that] ctDNA clearance retains its predictive value in this setting as well. Most MRD-positive patients who cleared ctDNA within 3 months post CAR T attained durable remission at 1 year. There was one patient who became ctDNA negative 1 month post CAR T, but then relapsed more than 1 year after, and this patient turned positive prior to recurrence. This suggests that single time point measurement post CAR T may not be sufficient, and longitudinal testing at various time intervals for several years of follow-up may be more optimal to detect patients who may relapse,” Galanina stated.

“MRD assessment supports the integration of ctDNA testing into routine clinical management and surveillance to personalize lymphoma care,” Galanina said in conclusion.

Disclosures: Galanina had no financial relationships to disclose.