George Russell stormed to the top of the timesheets in the final practice session for the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, marginally leading Lando Norris and Max Verstappen ahead of an all-important Qualifying hour.

The Mercedes driver found a small…

George Russell stormed to the top of the timesheets in the final practice session for the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, marginally leading Lando Norris and Max Verstappen ahead of an all-important Qualifying hour.

The Mercedes driver found a small…

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the EU energy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The EU will take a new top-down approach to building its cross-border energy grid, as the bloc’s energy chief warned of billions lost from bottlenecks and a failure to match supply with demand.

Brussels will develop a central plan to identify where investment is needed and will find projects to fill those gaps, in order to push EU countries to better co-ordinate energy infrastructure across borders and sectors.

Dan Jørgensen, the EU commissioner for energy, told the Financial Times that the “biggest danger” to the bloc’s decarbonisation and energy security goals was the slow construction of its power grid.

“In Europe, it’s a huge problem and we lose billions every year in lost value because of curtailment and bottlenecks,” he said.

Costs from grid congestion reached €5.2bn in 2022, and could rise to €26bn by 2030, according to figures from the EU energy regulator ACER.

The European Commission would work with member states and transmission system operators to find where investment was most needed, said Jørgensen, who insisted the new method would not constitute a power grab by Brussels.

“This is not a zero-sum game where the EU gets more power, thereby the member states get less power. Actually, by giving the EU new competences here, we will also empower member states to do more and better,” he said, adding that it marked a “paradigm shift” in infrastructure planning.

The EU, which was originally founded as a steel and coal union, has consistently struggled to improve its internal market for energy. An “energy union” that was first proposed in 2015 has yet to be completed.

“It is a bit of a paradox that we have an internal market that works better for selling tomatoes or toothpaste than it does for energy, since energy clearly is so important right now for our competitiveness, for our security and, of course, everybody wants to fight climate change,” Jørgensen said.

The rapid build-out of renewables such as wind and solar, which are far more volatile and dispersed power sources than gas or coal power plants, means there is an even greater need to upgrade and improve the grid.

The commission will develop “a comprehensive central EU scenario” for energy infrastructure planning, according to a draft document due to be presented next Wednesday.

Brussels would also undertake a “gap-filling” process, it said, that would “propose projects to address unmatched needs” in energy grids.

According to a report last month by the German think-tank Agora Energiewende, the EU could save more than €560bn between 2030 and 2050 if EU countries co-ordinated their energy infrastructure planning across sectors.

“A top-down approach to scenario-building would help identify areas where investment is needed,” the report said.

A major blackout on the Iberian peninsula in April and electricity price spikes in Greece last summer have strengthened the argument for more intervention from Brussels, officials have said.

Brussels will also establish an EU-level effort to simplify and speed up permitting procedures, which can take several years at present and hamper projects with a hefty administrative burden.

But Nicolás González Casares, a Spanish socialist lawmaker who led negotiations on the EU’s electricity market last year, said he was “particularly worried” that the commission’s new approach risked overriding environmental protections and creating legal uncertainty by assuming tacit approval for projects in order to speed up construction timelines. “The energy transition will only succeed if it is fast, but also fair and sustainable,” he said.

The first test of the new approach will be on eight proposed “energy highways”, which include interconnectors across the Pyrenees, cables linking Cyprus to mainland Europe and pipelines for hydrogen in south and south-west Europe.

The commission will also publish guidance for member states on prioritising critical projects for grid connection in an effort to reduce queues that are in some cases years long and have led to power-rationing in some countries.

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Few bankers are as closely associated with a single financial product as Hans-Jörg Rudloff. The Swiss-German banker might not have invented the eurobond, but he presided over its greatest period of growth — the 1980s — and dominated the hard-charging entrepreneurial firm that most embodied its spirit: Credit Suisse First Boston.

In some ways Rudloff, who has died at the age of 85, was an enigma. Despite spending his entire career in an industry often derided as cynical and greedy, he was also a visionary, believing sincerely in the power of finance to drive growth and improve people’s lives. “Capital markets have steered capital to all corners of this world and lifted billions of people out of poverty,” he said. It was a credo first formed on Wall Street in the late 1960s when, as a young bond salesman at Kidder Peabody, he witnessed the vigour and efficiency of New York’s financial markets, which he associated with the prosperity of American life.

This was a time when the US government, amid concerns about widening deficits during the Vietnam war, had slapped restrictions on exports of dollars. One unintended consequence was to spark into life a market centred in London but outside any national regulatory or tax control that shuffled offshore dollar deposits from investors into the hands of international corporations.

Rudloff moved back to Europe, keen to participate in this development, and in 1980 was recruited to a senior role at CSFB, then a new joint venture between Credit Suisse and the US investment bank First Boston. It was a propitious moment: the market was exploding, propelled by ever faster communications and the Thatcher-Reagan era rolling-back of currency controls.

Rudloff thrived in this highly competitive environment. For much of the 1980s, CSFB topped the league tables for eurobond issues. He acquired the sobriquet “king of the Euromarkets” for the invention of the “bought deal”. Instead of surveying the appetite of prospective investors before launching an issue, the underwriter would buy it outright, hoping to resell the bonds for a profit. Rudloff’s advantage, he once said, “was that I had permission to underwrite at 10 o’clock at night, whereas every other firm had to go to ten bloody committees to get any permission to underwrite anything”. It was a freedom he freely indulged, reportedly signing contracts over champagne at Annabel’s — a London nightclub of which he was an enthusiastic patron.

The one certainty in banking is that advantages conferred by innovation get whittled away, and by the end of the 1980s CSFB lost its lead to giant Japanese banks. The firm descended into infighting, some of it blamed on Rudloff’s confrontational style (he cheerfully described himself as “a bit more ruthless than other people”). Rudloff responded by leaving Credit Suisse and reinventing himself as an emerging markets banker, setting out to bring the benefits of capital markets to the newly freed countries beyond the Berlin Wall at a time when few investment banks dared to go there.

It was an adventure that catapulted him into the cockpit of Russian business in the era of Vladimir Putin, sitting on the board of the oil company Rosneft right until the outbreak of the Ukraine war. Rudloff continued to believe that in financing the reconstruction of eastern Europe, investment banking had “proved its worth, just as it did in 19th-century America”. But by the end of his life, he was dismayed to see the liberal, open world in which he believed was strongly in retreat.

Rudloff was born in wartime Cologne in 1940 to a German industrialist father and a Swiss mother. His dual nationality made him an outsider in the conservative world of Swiss finance, and perhaps impelled him to look beyond its borders. Small, bustling and intense, he always competed to the utmost. Unable to ski until later in life, Rudloff set out to rectify the situation, engaging a “crazy but enormously talented ski coach”, according to friend Bob Loverd, and systematically acquiring the skills of a pro. “If he decided to do something, he put everything he had into it,” Loverd recalled.

Rudloff could be polarising: his manner was often abrupt — even if the barbs were delivered with a twinkle. But to those he gave his friendship he was enormously loyal, and liked nothing more than to help those in whom he saw flashes of his younger self. “While he pushed you hard, he could be very kind,” said Charles Harman, a colleague at CSFB. “He would come round the floor at 8.30 in the evening and say: ‘Who wants dinner?’ to the juniors who were there. How many City bosses do that?” Rudloff’s last wish was to throw a party for his many friends.

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the first 10 months of 2025, investment trusts bought back more than £8.6bn worth of shares — 35 per cent more than in the same period last year. The aim was to close the discount between the share price of the trust and the value of the assets it contains per share. Did it work? Not very well; discounts remain stubbornly high for many trusts.

To explain why, we need to understand why there are discounts in the first place. This is a question I get asked a lot.

The big difference between an investment trust and a unit trust or “fund” comes when you want your money back. In an investment fund when lots of holders decide to sell units, the manager must dispose of underlying assets — and quickly. Fine if they’re liquid. Not so easy if those assets are something like property or a wind farm.

In a closed-ended investment trust, if you want your money back the manager doesn’t have to sell. The onus is on you to find a buyer for your shares. When the shares are less popular, buyers may offer less than the value of the underlying assets — a discounted price.

A discount, then, is the price you pay for liquidity, but it’s also an incentive for being patient. And that makes investment trusts an excellent vehicle for buying less liquid assets, like smaller companies, which can earn an illiquidity premium. This illiquidity reward is why over 25 years, for example, the smaller company equity index has outperformed the main market.

The discounts available today on income-generating assets can boost future returns significantly, too. If you buy £1 of assets for 90p you have the full £1 working to generate dividends, and that should compound over time. The closed-ended structure also allows gearing to be safely deployed, which can apply even more turbo to returns over time.

Today’s discounts — typically 14 per cent — are higher than average. We might expect them to close more than widen over the long term. But how? This year’s extraordinary level of share buybacks and windups has had little impact.

For a discount to close there needs to be a belief that the trust isn’t just a collection of assets. There needs to be a secret sauce — human expertise in managing the assets to enhance their value over time.

This has always been the case in the quoted property sector. A portfolio of properties will normally trade at a discount unless the managers can squeeze more out of the assets either by smart trading or by revitalising them.

The same was the case when the investment trust sector was used to inject capital into Lloyd’s of London. In 1992, the historic insurance market was on its knees and virtually bust. It needed a new supply of capital, which came with its plan of reconstruction and renewal.

Investment trusts were launched that pledged some of their capital to sit behind certain underwriting syndicates. The effect in the good insurance years was to boost the earnings of the investment trust, but a short-term earnings boost isn’t proof of a long-term earnings flow. The trusts went to discounts. The source of real value was the underwriting skills in some of the syndicates. And the trusts didn’t own that.

The answer in time was for the trusts — simply the providers of capital — to be folded into the managing agents that did the underwriting. Today, Lloyd’s insurer Hiscox trades at around 1.8 times its asset value, and many of the others that were originally investment trusts have been taken over at large multiples of book value. That experience is why I say it’s management skill that brings in discounts.

An area where there are currently large discounts is infrastructure and renewables. Too many managers have done little but buy assets. The dividends they generated when rates were low looked great, and the sector shot to a big premium. Rising rates have scuppered that. Those premiums are now deep discounts.

Many believe the answer is mergers and buybacks. But what is needed, in my view, is more proactive asset management. In fact, buybacks arguably only make the teams that want to be active despondent, because they have to be funded through disposals of the assets they would like to sweat.

What does this mean for the investor saving for the long term? Don’t get too hung up on discounts — they can work to your favour. Focus on the trusts that play to the structure’s strengths — that make the most of the illiquidity premium and of gearing, that give you access to assets you can’t buy easily, and where you can see the managers’ skill adding long-term value.

James Henderson is co-manager of the Lowland and Law Debenture investment trusts

Dana Arbib wants to move to a quieter, less frenzied part of New York City. But her neighbourhood – a highly mixed cross-section of downtown that straddles Little Italy and Chinatown, and is hemmed in by Soho – seems apt given who she is,…

If you like playing daily word games like Wordle, then Hurdle is a great game to add to your routine.

There are five rounds to the game. The first round sees you trying to guess the…

The festive shopping season is upon us and there is usually someone who is hard to buy for on the list. How can you avoid the stress of last-minute panic buying? Personal shoppers share their tips on how to treat your loved ones to something that they will cherish.

“A spreadsheet makes life so much easier,” says Clare Barry, a personal shopper and director of Victoria James Concierge, based in Sunningdale, Berkshire. “I set a budget, and I’ll think about what they like, what they’ve been doing this year, work out different options and start putting ideas against their name.” Barry says she has been working on her clients’ present lists since the summer. There are usually some last-minute pleas for help: “It is generally men,” Barry says.

Jennifer Nicholls from Watford works as a personal shopper as part of her An Hour Earned concierge business. She starts gathering her clients’ lists in October. “I spend a lot of time Googling things, and have lots and lots of deliveries. The postman hates me. At the moment, my flat is festooned with hundreds of gifts.”

Because she starts so early, Nicholls turns to the previous year’s gift guides for ideas of products and companies. This helps to create a portfolio of businesses that make unusual things, she says, and has the added benefit that items don’t sell out instantly, unlike suggestions on the current year’s guides.

“Always go for the best quality you can at the price that works for you,” says Nicholls. “I would avoid a brand name over something that feels better quality. It needs to feel solid and well built.” “Something that’s nicely made that you can tell is quality is always appreciated,” adds Barry.

Nicholls does most of her shopping online: “You can find more interesting, unique, quirky items much easier. I find that going to physical shops tends to be a bit samey.” But the quality of things you buy on the internet can sometimes disappoint: “Colours don’t translate properly; if the feel and quality isn’t quite right, I’ll return it,” says Nicholls. “I’m always careful to check the returns policy before I buy and the returns window so I don’t miss that.”

Buying locally can be more economical and helps small businesses rather than giving Jeff Bezos even more cash. “We have a responsibility to support local businesses and people who are out there building and making beautiful things,” says Nicholls.

There are some usual culprits who are difficult to buy for, like, “the neighbour down the road, the boss, the aunt you haven’t seen in a decade, but you still feel like you have to send something”, says Nicholls. “Food is always good, such as a hamper or some really nice chocolates … even if they personally don’t like it, a family member will.” Which is better, a small box of posh chocolates or a massive box of cheap ones? The former, says Barry – while you might buy a huge bar of Dairy Milk for a movie night, you might not get yourself a bougie box of truffles.

“If somebody is a busy parent or working every hour, then experience gifts are really fun,” says Nicholls. For example, buying a nail voucher for a friend who has just had a baby, “and looking after the baby so she can go out and get her nails done. It is about buying somebody time more than anything. Most people will be very grateful for that.” Always print out an experience voucher rather than just forwarding an email, says Barry. Or even better, put it in a gift box with an item related to the experience, such as a toy car if it is a race car driving day, or an Eiffel Tower figure if it is Eurostar tickets to Paris.

“The people most difficult to buy for are almost always those who have everything,” says Aoidín Sammon, a personal shopper in London. “For them I would always have something personalised.” Her go-to would be getting a passport cover or luggage tag monogrammed.

“Focus on their lifestyle, what they like to do, what they talk about, what they spend time on,” says Barry. “If they play golf a lot, and they’ve got everything for it, you could get something personalised for them, like a glove with their initials on. That makes such a huge difference: you’ve gone out of your way to do something different that they will always keep.” The same goes for a personalised notebook, says Barry, which she believes even in this day and age will still be coveted and used: “People like to take them to meetings”, she says, to show them off.

Something that works particularly well for men, who Nicholls says are often tricky, is to “buy them something they already have, but either an upgraded version or in a different colour. So if they wear lots of checked shirts buy them a checked shirt. You know they’re going to like it.” Nicholls also says fancy kitchen equipment can be a safe bet, as people often just buy basic stuff. “Gifting somebody a Le Creuset casserole dish that will last 30 years, or a really nice knife that’s going to be something they reach for regularly, is really useful. My mum gave me a cheese grater in my 20s and I’m still using it 20 years later.”

Needless to say Nicholls is a fan of practical presents: “I’m very much of the opinion that something that you can use is going to make a good gift, and also, every time you use it, you’re going to think of the person who gave it to you.” One of her favourite gifts ever was a pink toolkit from her grandfather, which she still uses regularly: “I think of him every time I pick it up.” Barry, though, is not a fan of practical gifts: “A gift should be something that you would love but you wouldn’t buy yourself. It’s a treat.” When a client suggests a new steam iron for their wife, “I say: ‘absolutely not!’ I think it’s grounds for divorce.”

“I would go down the jokey route,” says Nicholls. “Leave yourself plenty of time and search for ‘fun Secret Santa gifts’. The best one I ever found was an office voodoo kit.”

Barry says she has heard of people doing a challenge for their Secret Santa, where they can only spend £10 in a charity shop: “It’s great because you can come up with all sorts, but the charities benefit as well.”

“Children generally get far too much at Christmas,” says Barry. “We’ve had clients where the children didn’t even finish opening the gifts that they got on Christmas Day – they were still wrapped six months later.” She says “less is more” and advises on setting a firm budget and number of presents. “It means that they will appreciate what they’ve been given, and they will actually spend time looking at what they’ve got.”

“Most parents are not going to thank you for another plastic thing with lots of bits,” says Nicholls. She recommends experiences for kids: “Take them to the zoo, a museum, their first theatre trip. They are probably going to appreciate that more than a piece of plastic that they’ll play with for a day and then discard, and it gives their parents a break for an afternoon as well.” She also loves giving book tokens “because most parents want to encourage their children to read, and kids love being able to pick their own book”.

Shops sometimes offer a gift receipt; should you include it? “I think if you’re giving clothing, yes, because it’s easy to not get the style or the size right,” says Nicholls. “If you’re giving other things, I say no … You’re inviting them to not like it if you give them the receipt.” “For the most part there is no need,” says Sammon. “If lots of thought has gone into a gift, the receiver would not wish to return or exchange it.”

It can be awkward if you receive a gift you will not use and cannot return it. Is it acceptable to pass it on to someone else? “Regifting is very much OK in my mind,” says Sammon. “If you receive a candle or perfume that isn’t your scent, I see nothing wrong with regifting it to someone you feel will enjoy it more. There is so much waste at this time of year, we need to help reduce this.”

“I wouldn’t,” says Nicholls. “I find it uncomfortable but other people feel differently. I suppose there is something to be said for the gift going to a home of somebody who will appreciate it.”

“The wrapping is the first impression of the gift, so it deserves just as much consideration as what is inside,” says Sammon. “A gift won’t be quite as special if not wrapped with care.”

“I don’t believe in spending a fortune on wrapping paper,” says Barry. “Yes, it looks lovely when it is wrapped, but it is going to last three seconds as somebody then rips it off. But I do think if you’ve got the time to put ribbons on, that really does elevate the way your gifts look and are presented.” To make it look really magical, her top tip is brown paper, velvet ribbon and a sprig of holly.

When lacking in inspiration, turn to old favourites like socks, whisky and scarves. “A failsafe gift for a friend or family member is a really beautiful hand soap or hand cream,” says Sammon, but something more luxurious than normal. “You always need more soap!”

“It depends on who you’re giving them to,” says Nicholls. “If it is a close relative, like your mum, they might be a bit boring. You can come up with a spin on it to make it more interesting,” such as a subscription where you receive something like books for a few months. “If you’re buying it for your boss or somebody you’re not that close to, I think timeless is absolutely a great way to go: hampers, candles, you can’t go wrong with cashmere – pretty much everybody is going to be happy with some cashmere bed socks.”

“Alcohol, definitely,” says Barry. What if they don’t drink? “Then I don’t think we’d be friends,” she laughs. But if there was no booze: “I would get a gift bag and create a little kit. Say they love hot chocolate, I would buy hot chocolate and marshmallows.”

“A couple of bunches of flowers,” says Nicholls. “Take them out of the paper and re-tie them. Or I’d go for the nicest box of chocolates, if it was a Marks & Spencer. If it was the local Shell, I’d buy them the nicest antifreeze that was available and turn it into a joke. At the end of the day, it really is the thought that counts. It’s not about the stuff, it’s the thought behind it.”

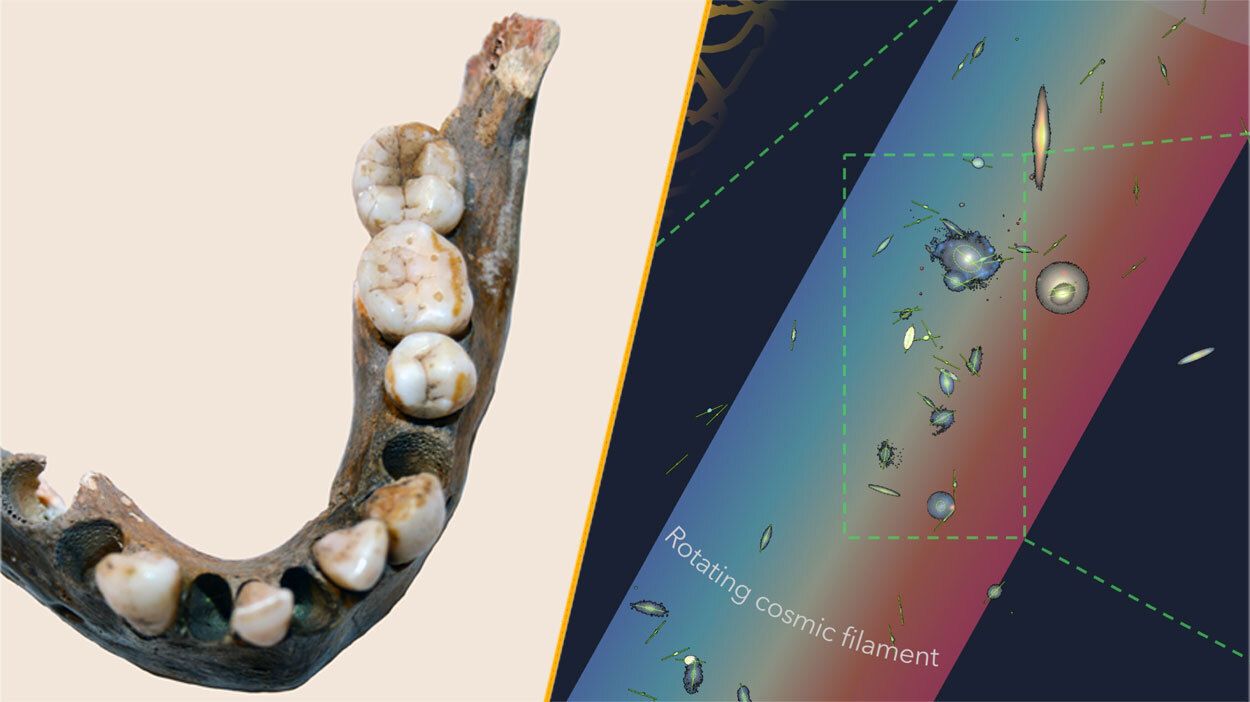

This week’s biggest science news took us to a region 140 million-light-years away, where scientists have discovered the largest spinning object in the known universe. The enormous rotating filament is wider than the Milky Way and is linked to…

Fresh border clashes have broken out between Pakistan and Afghanistan’s Taliban forces, with both sides accusing each other of breaking a fragile ceasefire.

Residents fled the Afghan city of Spin Boldak overnight, which lies along the 1,600-mile…