Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Commonwealth of Australia Penny Wong.

| Photo Credit: Reuters

Australia on Saturday imposed financial…

Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Commonwealth of Australia Penny Wong.

| Photo Credit: Reuters

Australia on Saturday imposed financial…

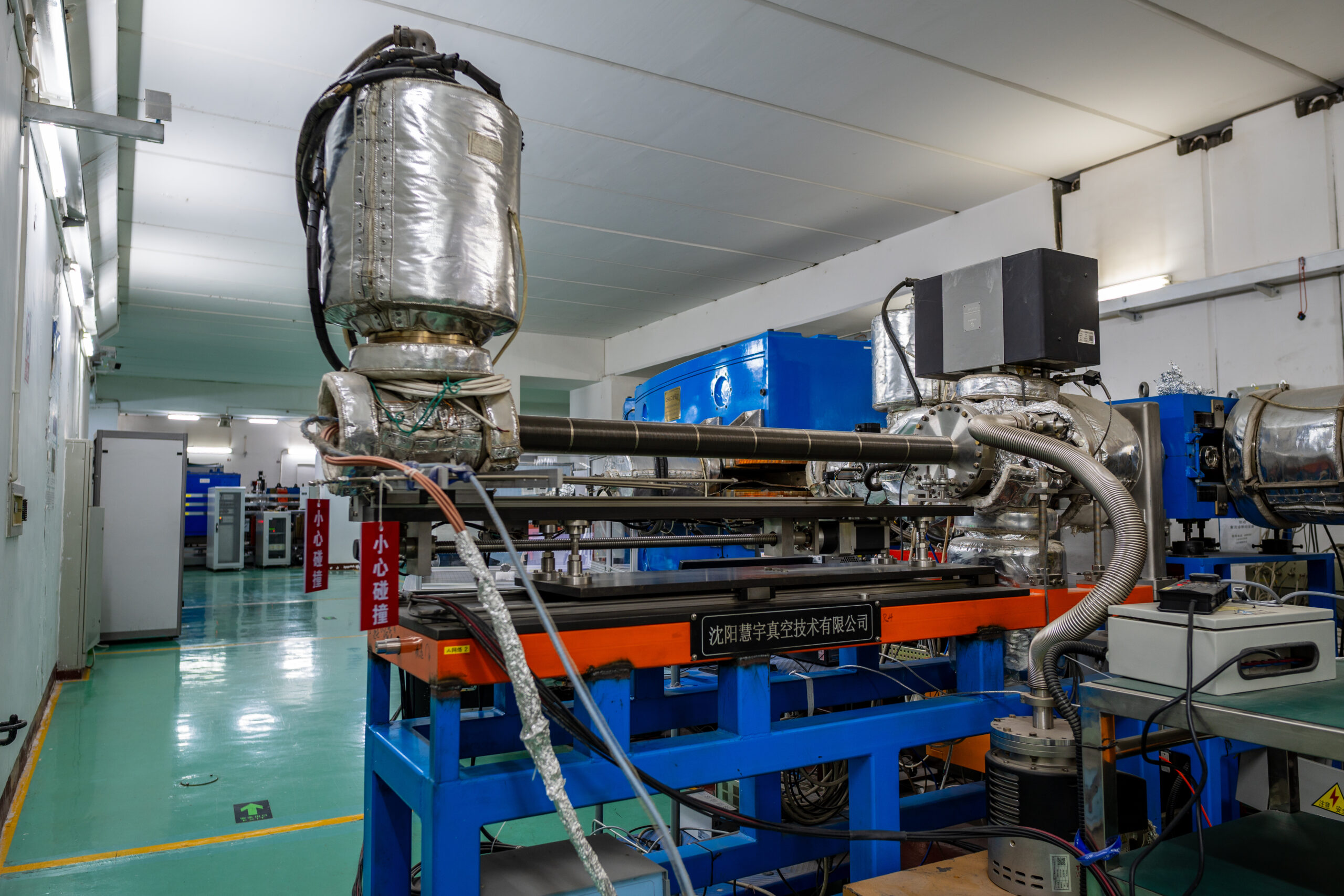

A research team from the Institute of Modern Physics (IMP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) has directly measured the masses of two highly unstable atomic nuclei, phosphorus-26 and sulfur-27. These precise measurements provide…

Density functional theory calculations, essential for modelling materials and plasmas, often demand substantial computational resources, prompting researchers to explore the power of modern graphics processing units. Atsushi M. Ito from the…

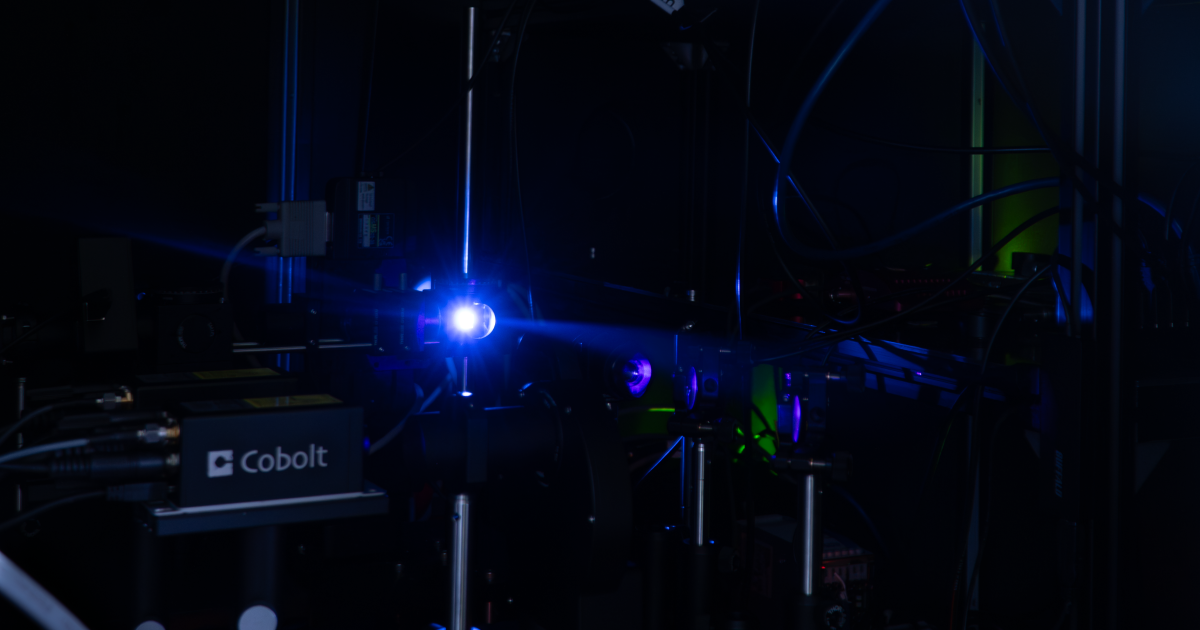

Why does plastic turn brittle and paint fade when exposed to the sun for long periods? Scientists have long known that such organic photodegradation occurs due to the sun’s energy generating free radicals: molecules that have lost an electron to…

Dec 6 (Reuters) – The World bank Group said on Saturday it was working with the global vaccine alliance Gavi to strengthen financing for immunization and primary healthcare systems, planning to mobilize at least $2 billion over the next five…

Scientists have unveiled a technique that uses ‘molecular antennas’ to direct electrical energy into insulating nanoparticles. This approach creates a new family of ultra-pure near-infrared LEDs that could be used in medical diagnostics, optical…

Rucaparib (Rubraca) significantly improved radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) vs physician’s choice of docetaxel or androgen receptor pathway inhibition (ARPI) in patients with BRCA-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate…