Skywatchers are in for a stunning spectacle this week when the second-biggest full moon of 2025, the Cold Supermoon, rises in the east at dusk and appears higher in the night sky than any other full moon of the year.

Officially full at 6:14 p.m….

Skywatchers are in for a stunning spectacle this week when the second-biggest full moon of 2025, the Cold Supermoon, rises in the east at dusk and appears higher in the night sky than any other full moon of the year.

Officially full at 6:14 p.m….

On the Shelf

Superhero

By Tim Blake Nelson

Unnamed Press: 424 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Picture 14-year-old Tim…

MONTROSE, California — In the world’s most impoverished communities, danger lurks in flooded fields, muddy riverbanks and puddles outside homes. Leptospirosis, a bacterial disease transmitted from animals to humans, kills more…

2025 was a banner year for cookbooks. These new titles? They helped us get dinner on the table in so many ways. Books for those willing to explore the wonders waiting in their pantry, or those who want to wander around other countries for…

A new study published in BMJ Public Health finds that extrafamilial violence (EFV), such as bullying, collective, and community violence, is linked to mental health issues, substance use, chronic pain, and frequent health service…

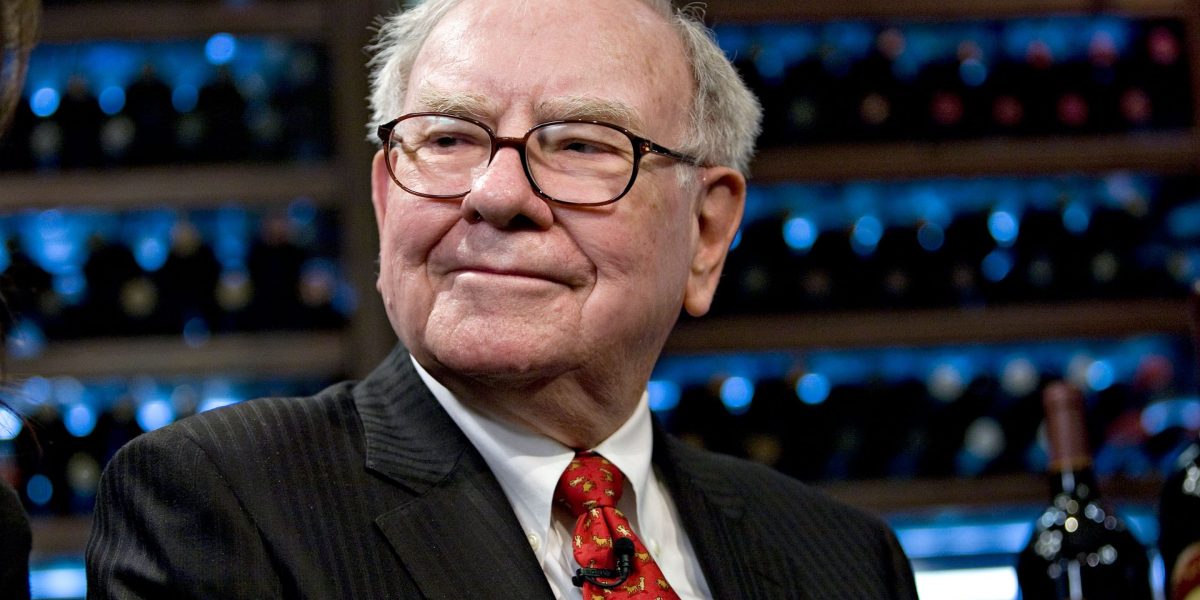

The ‘Oracle of Omaha,’ Warren Buffett, is famed for his investment prowess. So it’s perhaps no surprise that when he learned his family members were blowing the thousands of dollars he gifted them each year, he changed tack and began buying them shares instead.

Come the most wonderful time of the year, members of the Buffett family previously looked forward to receiving $10,000 in hundred-dollar bills. Buffett’s former daughter-in-law, Mary Buffett—who was married to the Berkshire Hathaway CEO’s son, Peter—said as soon as the guests returned home after Christmas Day, they would splash the cash.

Mary told ThinkAdvisor in 2019: “As soon as we got home, we’d spend it, whoo!”

This likely displeased the man worth $154 billion, whose financial ethos revolves around playing the long game and sensible spending. Mary added: “Then, one Christmas there was an envelope with a letter from him. Instead of cash, he’d given us $10,000 worth of shares in a company he’d recently bought, a trust Coca-Cola had. He said to either cash them in or keep them.”

Perhaps taking inspiration from her father-in-law at last, Mary decided to hold onto the shares: “I thought ‘Well, [this stock] is worth more than $10,000.’ So I kept it, and it kept going up.”

Every year after that, Buffett would continue to gift his family members stocks, which included Wells Fargo one year. It’s a good pick: Even in 2025, Wells Fargo is up 21.9%, and is up more than 200% over the past five years.

Mary began to follow Buffett’s lead, saying that if he bought the shares, she would then go and “buy more of it, because I knew it was going to go up.”

Buffett’s family also faced quite a conundrum come December each year: How do you reciprocate a gift worth $10,000 or more? This is made all the more complicated by the question of what to buy a billionaire.

Mary decided the best gift she could give the now 95-year-old was to demonstrate that his children and their families were successful in their own right. “The first year we were married, I realized, ‘Warren is very rich. Therefore, he doesn’t want anything,’” Mary recalled, and instead shared with him the balance sheet for the music company she ran. “I just wanted to show him ‘Look, we’re doing good,’” she added.

With December upon us, families around the world will be gearing up to spend a significant amount on their loved ones. And like Buffett in the early years, now is the time of year when many will be gifting lump sums of cash to their families.

According to UK insurance giant SunLife, more than one in five people over the age of 50 have given a significant amount of money as a present in the past five years. Of those people, 33% of them coincided it with Christmas or a special birthday.

The biggest form of cash gifts was for house deposits, and they were significant sums as a result. SunLife, which surveyed more than 2,000 people, found people aged over 50 gifted, on average, £30,634 ($40,568). The next largest gifts were for help with home renovations, with an average of £8,932 ($11,828).

Younger generations are likely to get more used to receiving cash gifts from their older relatives in the decades to come, courtesy of the Great Wealth Transfer. The inheritance wave is worth some $83 trillion according to UBS, and will take place over the next 20 to 25 years.

Reports have previously suggested that a $9 trillion ‘sideways’ wealth transfer from husbands to their wives has resulted in an uptick in investment—straight out of the Buffett playbook. It remains to be seen whether younger generations will follow suit.

At a recent Q&A for the film that I wrote and directed, “A Little Prayer,” someone asked me, “Why did you want to tell this story?” I bumbled and came out with something along the lines of “Who knows?”: The process is mysterious, the…

“The Testament of Ann Lee” stars Amanda Seyfried as the founder of the Shakers, a religious sect formed in the 18th century and known for both its pursuit of full social equality and its chants and dances designed to rid the body of sin….

Terrelonge also notes that the kind of fabrics found in these countryside styles, the waxed cottons, leathers and tweeds, are aspirational, in an understated rather than showy way. Plus, for the wearer, there’s a quiet confidence lent to them by…

On Nov. 2, 2025, NASA honored 25 years of continuous human presence aboard the International Space Station. What began as a fragile framework of modules has evolved into a springboard for international cooperation, advanced scientific research…