The 2025 Continental Classic is here!

And on Monday night, we were introduced to the 12 wrestlers who will participate in this year’s Continental Classic, beginning on the Thanksgiving Eve AEW Dynamite this Wednesday, live at 8 p.m. ET/7 p.m….

The 2025 Continental Classic is here!

And on Monday night, we were introduced to the 12 wrestlers who will participate in this year’s Continental Classic, beginning on the Thanksgiving Eve AEW Dynamite this Wednesday, live at 8 p.m. ET/7 p.m….

Our commitment to delivering the best personal service

defines our business and inspires our efforts every day.

We’re accessible and responsive to every…

US President Donald Trump has ordered officials to examine whether to designate some chapters of the Muslim Brotherhood as terrorists groups, a move that would target the group with economic and travel sanctions.

His executive order on Monday…

Esmaeili ED, Azizi H, Dastgiri S, Kalankesh LR. Does telehealth affect the adherence to ART among patients with HIV? a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:169.

Jahagirdar…

Pakistani strikes on Afghanistan overnight killed at least 10 people, Taliban government spokesman said Tuesday. Among those killed, nine are children and — five boys and four girls — and one woman.“The Pakistani invading forces bombed the…

Looking for the most recent Mini Crossword answer? Click here for today’s Mini Crossword hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Wordle, Strands, Connections and Connections: Sports Edition puzzles.

Need some help…

The United Kingdom’s Rivals was named Best Drama Series on Monday at the 53rd International Emmy Awards in New York City.

Hosted by Kelly Ripa and Mark Consuelos, winners were announced in 16 categories, drawn from 64 nominees from a…

Browsing a list of 100 books is exciting, but can be overwhelming. Want to find one to read right away? We can help! Here is a cheat sheet to the list, broken into categories. Clicking a book cover will take you to the full review.

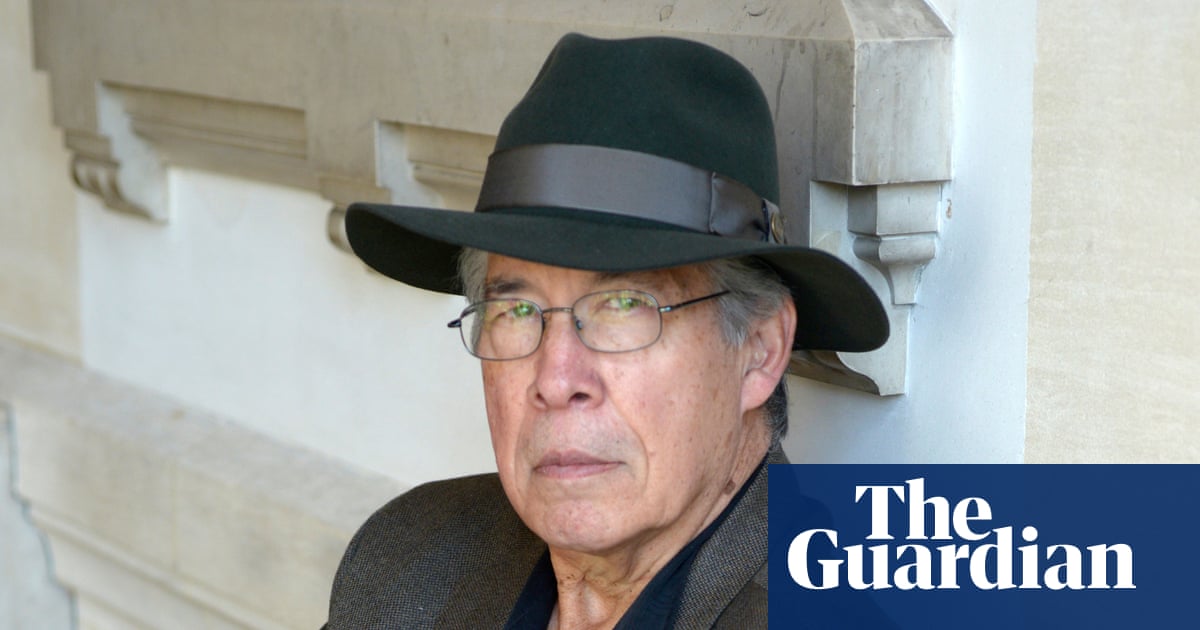

A prominent Canadian-American author, who has long claimed Indigenous ancestry and whose work exposed “the hard truths of the injustices of the Indigenous peoples of North America”, has learned from a genealogist that he has no Cherokee…