villa nuri completes in lush costa rica

Studio Saxe‘s newly completed Villa Nuri occupies a narrow slope in Costa Rica where sunlight and lush forests guide the flow of daily life. The home presents a sequence of elevated rooms and terraces…

Studio Saxe‘s newly completed Villa Nuri occupies a narrow slope in Costa Rica where sunlight and lush forests guide the flow of daily life. The home presents a sequence of elevated rooms and terraces…

There are many ways to interpret Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s visit last week to Washington, but I found my colleagues at Semafor’s description of the agreements as a “two-way street” apt. The framing matters. As the…

(Bagnolet: November 24, 2025) In the face of UN Security Council Resolution 2803 (2025), it becomes unmistakably clear that what is being offered to the world as a “framework for stability” is, in fact, one of the gravest international…

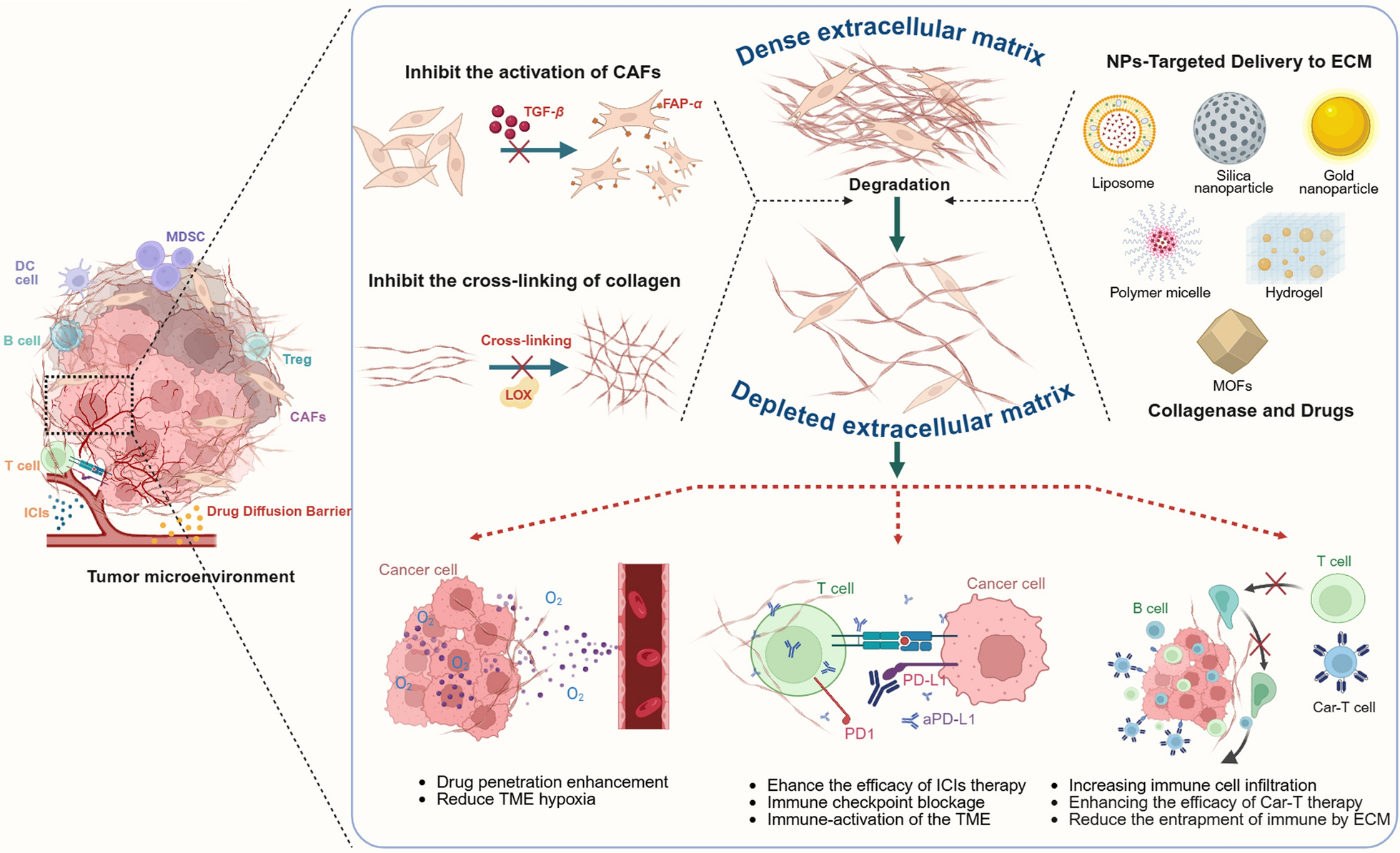

Sleeboom JJF, van Tienderen GS, Schenke-Layland K, van der Laan LJW, Khalil AA, Verstegen MMA. The extracellular matrix as hallmark of cancer and metastasis: from biomechanics to therapeutic targets. Sci Transl Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.adg3840.

Google Scholar

Paolillo M, Schinelli S. Extracellular matrix alterations in metastatic processes. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20194947.

Google Scholar

Glabman RA, Choyke PL, Sato N. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: tumorigenicity and targeting for cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3906. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14163906.

Google Scholar

Roma-Rodrigues C, Mendes R, Baptista PV, Fernandes AR. Targeting tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040840.

Google Scholar

Kai F, Drain AP, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the metastatic journey. Dev Cell. 2019;49:332–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2019.03.026.

Google Scholar

Yuan Z, Li Y, Zhang S, Wang X, Dou H, Yu X, et al. Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: from mechanisms to treatments. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01744-8.

Google Scholar

Xiong J, Xiao R, Zhao J, Zhao Q, Luo M, Li F, et al. Matrix stiffness affects tumor-associated macrophage functional polarization and its potential in tumor therapy. J Transl Med. 2024;22:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04810-3.

Google Scholar

Deng B, Zhao Z, Kong W, Han C, Shen X, Zhou C. Biological role of matrix stiffness in tumor growth and treatment. J Transl Med. 2022;20:540. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03768-y.

Google Scholar

Zeltz C, Primac I, Erusappan P, Alam J, Noel A, Gullberg D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in desmoplastic tumors: emerging role of integrins. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;62:166–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.004.

Google Scholar

De Palma M, Biziato D, Petrova TV. Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:457–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2017.51.

Google Scholar

Kugeratski FG, Atkinson SJ, Neilson LJ, Lilla S, Knight JRP, Serneels J, et al. Hypoxic cancer-associated fibroblasts increase NCBP2-AS2/HIAR to promote endothelial sprouting through enhanced VEGF signaling. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaan8247. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aan8247.

Google Scholar

Dzobo K, Dandara C. The extracellular matrix: its composition, function, remodeling, and role in tumorigenesis. Biomimetics. 2023;8:146. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8020146.

Google Scholar

Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Gialeli C, Karamanos NK. Extracellular matrix structure. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;97:4–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.001.

Google Scholar

He X, Yang Y, Li L, Zhang P, Guo H, Liu N, et al. Engineering extracellular matrix to improve drug delivery for cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:1727–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2020.06.029.

Google Scholar

Gouarderes S, Mingotaud A-F, Vicendo P, Gibot L. Vascular and extracellular matrix remodeling by physical approaches to improve drug delivery at the tumor site. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2020;17:1703–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425247.2020.1814735.

Google Scholar

Morin PJ. Drug resistance and the microenvironment: nature and nurture. Drug Resist Updat. 2003;6:169–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1368-7646(03)00059-1.

Google Scholar

Stylianopoulos T, Munn LL, Jain RK. Reengineering the physical microenvironment of tumors to improve drug delivery and efficacy: from mathematical modeling to bench to bedside. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:292–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2018.02.005.

Google Scholar

Diener B, Carrick L, Berk RS. In vivo studies with collagenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1973;7:212–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.7.2.212-217.1973.

Google Scholar

Lammers T. Nanomedicine tumor targeting. Adv Mater. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202312169.

Google Scholar

Hebert JD, Myers SA, Naba A, Abbruzzese G, Lamar JM, Carr SA, et al. Proteomic profiling of the ECM of xenograft breast cancer metastases in different organs reveals distinct metastatic niches. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1475–85. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2961.

Google Scholar

Naba A, Clauser KR, Lamar JM, Carr SA, Hynes RO. Extracellular matrix signatures of human mammary carcinoma identify novel metastasis promoters. Elife. 2014;3:e01308. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.01308.

Google Scholar

Mai Z, Lin Y, Lin P, Zhao X, Cui L. Modulating extracellular matrix stiffness: a strategic approach to boost cancer immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15:307. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-06697-4.

Google Scholar

Cheng PSW, Zaccaria M, Biffi G. Functional heterogeneity of fibroblasts in primary tumors and metastases. Trends Cancer. 2025;11:135–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2024.11.005.

Google Scholar

Barbazán J, Matic Vignjevic D. Cancer associated fibroblasts: is the force the path to the dark side? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2019;56:71–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2018.09.002.

Google Scholar

Chen Y, McAndrews KM, Kalluri R. Clinical and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:792–804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-021-00546-5.

Google Scholar

Margadant C, Sonnenberg A. Integrin–TGF-β crosstalk in fibrosis, cancer and wound healing. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:97–105. https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2009.276.

Google Scholar

Strating E, Verhagen MP, Wensink E, Dünnebach E, Wijler L, Aranguren I, et al. Co-cultures of colon cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts recapitulate the aggressive features of mesenchymal-like colon cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1053920. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1053920.

Google Scholar

Yang Y, Sun H, Yu H, Wang L, Gao C, Mei H, et al. Tumor-associated-fibrosis and active collagen-CD44 axis characterize a poor-prognosis subtype of gastric cancer and contribute to tumor immunosuppression. J Transl Med. 2025;23:123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-06070-9.

Google Scholar

Bigos KJA, Quiles CG, Lunj S, Smith DJ, Krause M, Troost EGC, et al. Tumour response to hypoxia: understanding the hypoxic tumour microenvironment to improve treatment outcome in solid tumours. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1331355. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1331355.

Google Scholar

Rubinstein-Achiasaf L, Morein D, Ben-Yaakov H, Liubomirski Y, Meshel T, Elbaz E, et al. Persistent inflammatory stimulation drives the conversion of MSCs to inflammatory CAFs that promote pro-metastatic characteristics in breast cancer cells. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061472.

Google Scholar

Cox TR. The matrix in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-020-00329-7.

Google Scholar

Connor A, Gallinger S. Pancreatic cancer evolution and heterogeneity: integrating omics and clinical data. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22:131–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-021-00418-1.

Google Scholar

Zhang J, Miao L, Guo S, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Satterlee A, et al. Synergistic anti-tumor effects of combined gemcitabine and cisplatin nanoparticles in a stroma-rich bladder carcinoma model. J Control Release. 2014;182:90–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.016.

Google Scholar

Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, Mizuno K, Chen Q, Murakami M, Kimura M, et al. Accumulation of sub-100 nm polymeric micelles in poorly permeable tumours depends on size. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:815–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2011.166.

Google Scholar

Stylianopoulos T, Jain RK. Combining two strategies to improve perfusion and drug delivery in solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18632–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1318415110.

Google Scholar

Li Q, Yang C, Li J, Wang R, Min J, Song Y, et al. The type I collagen paradox in PDAC progression: microenvironmental protector turned tumor accomplice. J Transl Med. 2025;23:744. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-06778-8.

Google Scholar

Masamune A, Kikuta K, Watanabe T, Satoh K, Hirota M, Hamada S, et al. Fibrinogen induces cytokine and collagen production in pancreatic stellate cells. Gut. 2009;58:550–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2008.154401.

Google Scholar

Bulle A, Lim K-H. Beyond just a tight fortress: contribution of stroma to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00341-1.

Google Scholar

Feig C, Gopinathan A, Neesse A, Chan DS, Cook N, Tuveson DA. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4266–76. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114.

Google Scholar

Karousou E, D’Angelo ML, Kouvidi K, Vigetti D, Viola M, Nikitovic D, et al. Collagen VI and Hyaluronan: The Common Role in Breast Cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:606458. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/606458.

Google Scholar

Fang M, Yuan J, Peng C, Li Y. Collagen as a double-edged sword in tumor progression. Tumor Biol. 2014;35:2871–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-013-1511-7.

Google Scholar

Yu S, Zhang C, Xie K-P. Therapeutic resistance of pancreatic cancer: roadmap to its reversal. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). 2021;1875:188461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188461.

Google Scholar

Hosein AN, Brekken RA, Maitra A. Pancreatic cancer stroma: an update on therapeutic targeting strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:487–505. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-0300-1.

Google Scholar

Heydari S, Tajik F, Safaei S, Kamani F, Karami B, Dorafshan S, et al. The association between tumor-stromal collagen features and the clinical outcomes of patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. 2025;27:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-025-02017-6.

Google Scholar

Hruska AM, Yang H, Leggett SE, Guo M, Wong IY. Mechanobiology of Collective Cell Migration in 3D Microenvironments. 2023; 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22802-5_1

Henke E, Nandigama R, Ergun S. Extracellular matrix in the tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer therapy. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;6:160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2019.00160.

Google Scholar

Netti PA, Berk DA, Swartz MA, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK. Role of extracellular matrix assembly in interstitial transport in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2497–503.

Google Scholar

Sykes EA, Dai Q, Sarsons CD, Chen J, Rocheleau JV, Hwang DM, et al. Tailoring nanoparticle designs to target cancer based on tumor pathophysiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1142-51. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521265113.

Google Scholar

Pluen A, Boucher Y, Ramanujan S, McKee TD, Gohongi T, di Tomaso E, et al. Role of tumor–host interactions in interstitial diffusion of macromolecules: cranial vs. subcutaneous tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4628–33. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.081626898.

Google Scholar

Nichols JW, Bae YH. Odyssey of a cancer nanoparticle: from injection site to site of action. Nano Today. 2012;7:606–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2012.10.010.

Google Scholar

Ramanujan S, Pluen A, McKee TD, Brown EB, Boucher Y, Jain RK. Diffusion and convection in collagen gels: implications for transport in the tumor interstitium. Biophys J. 2002;83:1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73933-7.

Google Scholar

Erikson A, Andersen HN, Naess SN, Sikorski P, Davies CdeL. Physical and chemical modifications of collagen gels: impact on diffusion. Biopolymers. 2008;89:135–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.20874.

Google Scholar

Chauhan VP, Lanning RM, Diop-Frimpong B, Mok W, Brown EB, Padera TP, et al. Multiscale measurements distinguish cellular and interstitial hindrances to diffusion in vivo. Biophys J. 2009;97:330–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.064.

Google Scholar

He X, Yang Y, Han Y, Cao C, Zhang Z, Li L, et al. Extracellular matrix physical properties govern the diffusion of nanoparticles in tumor microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2209260120.

Google Scholar

Park JE, Lenter MC, Zimmermann RN, Garin-Chesa P, Old LJ, Rettig WJ. Fibroblast activation protein, a dual specificity serine protease expressed in reactive human tumor stromal fibroblasts*. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36505–12. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.51.36505.

Google Scholar

Santos AM, Jung J, Aziz N, Kissil JL, Puré E. Targeting fibroblast activation protein inhibits tumor stromagenesis and growth in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3613–25. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI38988.

Google Scholar

Murakami M, Ernsting MJ, Undzys E, Holwell N, Foltz WD, Li S-D. Docetaxel conjugate nanoparticles that target α-smooth muscle actin-expressing stromal cells suppress breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4862–71. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0062.

Google Scholar

Teng F, Tian W-Y, Wang Y-M, Zhang Y-F, Guo F, Zhao J, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote the progression of endometrial cancer via the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-015-0231-4.

Google Scholar

Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11183.

Google Scholar

Duluc C, Moatassim-Billah S, Chalabi-Dchar M, Perraud A, Samain R, Breibach F, et al. Pharmacological targeting of the protein synthesis mTOR/4E-BP1 pathway in cancer-associated fibroblasts abrogates pancreatic tumour chemoresistance. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:735–53. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201404346.

Google Scholar

Huang S, Rui F, Jun X, Shenghong Q, Huan Z, Jun D, et al. Evaluation of the tumor targeting of a FAPα-based doxorubicin prodrug. J Drug Target. 2011;19:487–96. https://doi.org/10.3109/1061186X.2010.511225.

Google Scholar

Akinboye ES, Brennen WN, Rosen DM, Bakare O, Denmeade SR. Iterative design of emetine-based prodrug targeting fibroblast activation protein (FAP) and dipeptidyl peptidase IV DPPIV using a tandem enzymatic activation strategy. Prostate. 2016;76:703–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.23162.

Google Scholar

Eikenes L, Bruland ØS, Brekken C, Davies CDL. Collagenase increases the transcapillary pressure gradient and improves the uptake and distribution of monoclonal antibodies in human osteosarcoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4768–73. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1472.

Google Scholar

Kato M, Hattori Y, Kubo M, Maitani Y. Collagenase-1 injection improved tumor distribution and gene expression of cationic lipoplex. Int J Pharm. 2012;423:428–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.12.015.

Google Scholar

McKee TD, Grandi P, Mok W, Alexandrakis G, Insin N, Zimmer JP, et al. Degradation of fibrillar collagen in a human melanoma xenograft improves the efficacy of an oncolytic Herpes simplex virus vector. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2509–13. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2242.

Google Scholar

Kim M, Hamilton SE, Guddat LW, Overall CM. Plant collagenase: unique collagenolytic activity of cysteine proteases from ginger. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). 2007;1770:1627–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.08.003.

Google Scholar

Raskovic B, Bozovic O, Prodanovic R, Niketic V, Polovic N. Identification, purification and characterization of a novel collagenolytic serine protease from fig (Ficus carica var. Brown Turkey) latex. J Biosci Bioeng. 2014;118:622–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.05.020.

Google Scholar

Peptidase M9A/M9B, collagenase, bacterial . [cited 2025 Jul 29]. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/InterPro/IPR002169/. Accessed 29 Jul 2025

Q9X721 · COLG_HATHI [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 29]. https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q9X721/entry. Accessed 29 Jul 2025

Collagenase [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 29]. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/pfam/PF01752/. Accessed 29 Jul 2025

Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D343–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr987.

Google Scholar

Mookhtiar KA, Van Wart HE. Clostridium histolyticum collagenases: a new look at some old enzymes. Matrix. 1992;1(Suppl):116–26.

Google Scholar

Hoy SM. Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum: a review in Peyronie’s disease. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40:83–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-019-00867-5.

Google Scholar

Van Wart HE, Steinbrink DR. A continuous spectrophotometric assay for Clostridium histolyticum collagenase. Anal Biochem. 1981;113:356–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(81)90089-0.

Google Scholar

Matsushita O, Koide T, Kobayashi R, Nagata K, Okabe A. Substrate recognition by the collagen-binding domain of Clostridium histolyticum class I collagenase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8761–70. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M003450200.

Google Scholar

Matsushita O, Jung C-M, Minami J, Katayama S, Nishi N, Okabe A. A study of the collagen-binding domain of a 116-kDa Clostridium histolyticum collagenase*. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(6):3643–8. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.6.3643.

Google Scholar

Matsushita O, Jung C-M, Katayama S, Minami J, Takahashi Y, Okabe A. Gene duplication and multiplicity of collagenases in Clostridium histolyticum. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:923–33. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.181.3.923-933.1999.

Google Scholar

The R-B, Family C. The Collagen Family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004978–a004978. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a004978.

Google Scholar

Bella J, Hulmes DJS. Fibrillar Collagens. Fibrous Prot Struct Mech. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49674-0_14.

Google Scholar

Amirrah IN, Lokanathan Y, Zulkiflee I, Wee MFMR, Motta A, Fauzi MB. A comprehensive review on collagen type I development of biomaterials for tissue engineering: from biosynthesis to bioscaffold. Biomedicines. 2022;10:2307. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10092307.

Google Scholar

Eckhard U, Schönauer E, Nüss D, Brandstetter H. Structure of collagenase G reveals a chew and digest mechanism of bacterial collagenolysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1109–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2127.

Google Scholar

Eckhard U, Schönauer E, Brandstetter H. Structural basis for activity regulation and substrate preference of clostridial collagenases G, H, and T. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20184–94. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.448548.

Google Scholar

Syed F, Thomas AN, Singh S, Kolluru V, Emeigh Hart SG, Bayat A. In vitro study of novel collagenase (XIAFLEX®) on Dupuytren’s disease fibroblasts displays unique drug related properties. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31430. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031430.

Google Scholar

Watanabe-Nakayama T, Itami M, Kodera N, Ando T, Konno H. High-speed atomic force microscopy reveals strongly polarized movement of clostridial collagenase along collagen fibrils. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28975. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28975.

Google Scholar

Mandl I. Bacterial collagenases and their clinical applications. Arzneimittelforschung. 1982;32:1381–4.

Google Scholar

Ramundo J, Gray M. Collagenase for enzymatic debridement: a systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36:S4. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0b013e3181bfdf83.

Google Scholar

Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. [cited 2025 Jul 29]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=BasicSearch.process. Accessed 29 Jul 2025

Waycaster C, Milne CT. Clinical and economic benefit of enzymatic debridement of pressure ulcers compared to autolytic debridement with a hydrogel dressing. J Med Econ. 2013;16:976–86. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2013.807268.

Google Scholar

Ramundo J, Gray M. Enzymatic wound debridement. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008;35:273. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.WON.0000319125.21854.78.

Google Scholar

Kirshen C, Woo K, Ayello EA, Sibbald RG. Debridement: a vital component of wound bed preparation. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19:518.

Google Scholar

Karagol BS, Okumus N, Dursun A, Karadag N, Zencıroglu A. Early and successful enzymatic debridement via collagenase application to pinna in a preterm neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:600–1. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01546.x.

Google Scholar

Waycaster C, Carter MJ, Gilligan AM, Mearns ES, Fife CE, Milne CT. Comparative cost and clinical effectiveness of clostridial collagenase ointment for chronic dermal ulcers. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7:149–65. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2017-0066.

Google Scholar

Abdel Raheem A, Johnson M, Ralph D, Garaffa G. Collagenase clostridium histolyticum: a novel medical treatment for Peyronie’s disease. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0393-2249.18.03118-1.

Google Scholar

Furtado TP, Osadchiy V, Andino JJ, Eleswarapu SV, Mills JN. Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Peyronie’s disease: a contemporary atlas of complications and their management. Sex Med Rev. 2024;12:491–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/sxmrev/qeae004.

Google Scholar

FDA Approves Xiaflex for Debilitating Hand Condition. [cited 2025 Jul 29]. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fda-approves-xiaflex-for-debilitating-hand-condition-83391072.html. Accessed 29 Jul 2025

Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, Hotchkiss RN, Kaplan FTD, Meals RA, et al. Injectable collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:968–79. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810866.

Google Scholar

Peimer CA, Wilbrand S, Gerber RA, Chapman D, Szczypa PP. Safety and tolerability of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum and fasciectomy for Dupuytren’s contracture. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40:141–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193414528843.

Google Scholar

Lunt SJ, Fyles A, Hill RP, Milosevic M. Interstitial fluid pressure in tumors: therapeutic barrier and biomarker of angiogenesis. Future Oncol. 2008;4:793–802. https://doi.org/10.2217/14796694.4.6.793.

Google Scholar

Cairns R, Papandreou I, Denko N. Overcoming physiologic barriers to cancer treatment by molecularly targeting the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:61–70. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0002.

Google Scholar

Yata T, Lee ELQ, Suwan K, Syed N, Asavarut P, Hajitou A. Modulation of extracellular matrix in cancer is associated with enhanced tumor cell targeting by bacteriophage vectors. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-015-0383-4.

Google Scholar

Cemazar M, Golzio M, Sersa G, Escoffre J-M, Coer A, Vidic S, et al. Hyaluronidase and collagenase increase the transfection efficiency of gene electrotransfer in various murine tumors. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:128–37. https://doi.org/10.1089/hum.2011.073.

Google Scholar

Lo Cicero A, Campora S, Lo Buglio G, Cinà P, Lo Pinto M, Scilabra SD, et al. Enhancing therapeutic efficacy through degradation of endogenous extracellular matrix in primary breast tumor spheroids. FEBS J. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.70069.

Google Scholar

Fan D, Cao Y, Cao M, Wang Y, Cao Y, Gong T. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:1–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01536-y.

Google Scholar

Fang J, Nakamura H, Maeda H. The EPR effect: unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:136–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.009.

Google Scholar

Maeda H. Macromolecular therapeutics in cancer treatment: the EPR effect and beyond. J Control Release. 2012;164:138–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.038.

Google Scholar

Wang Y, Zhou Q, Luo W, Yang X, Zhang J, Lou Y, et al. A collagenase-decorated Cu-based nanotheranostics: remodeling extracellular matrix for optimizing cuproptosis and MRI in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:689. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02968-6.

Google Scholar

Abdel-Hafez SM, Gallei M, Wagner S, Schneider M. Inhalable nano-structured microparticles for extracellular matrix modulation as a potential delivery system for lung cancer. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2024;204:114512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2024.114512.

Google Scholar

Liu Q, Zou J, Chen Z, He W, Wu W. Current research trends of nanomedicines. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:4391–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.018.

Google Scholar

Koo H, Huh MS, Sun I-C, Yuk SH, Choi K, Kim K, et al. In vivo targeted delivery of nanoparticles for theranosis. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1018–28. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar2000138.

Google Scholar

Janib SM, Moses AS, MacKay JA. Imaging and drug delivery using theranostic nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1052–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.004.

Google Scholar

Bae YH, Park K. Targeted drug delivery to tumors: myths, reality and possibility. J Control Release. 2011;153:198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.001.

Google Scholar

Zinger A, Koren L, Adir O, Poley M, Alyan M, Yaari Z, et al. Collagenase nanoparticles enhance the penetration of drugs into pancreatic tumors. ACS Nano. 2019;13:11008–21. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b02395.

Google Scholar

Liu X, Dong X, Peng Z, Wang C, Wan J, Chen M, et al. Collagenase-functionalized liposomes based on enhancing penetration into the extracellular matrix augment therapeutic effect on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2025;26:113. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-025-03112-9.

Google Scholar

Zhou L, Liang Q, Li Y, Cao Y, Li J, Yang J, et al. Collagenase-I decorated co-delivery micelles potentiate extracellular matrix degradation and hepatic stellate cell targeting for liver fibrosis therapy. Acta Biomater. 2022;152:235–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2022.08.065.

Google Scholar

Yu B, Wang W, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Li C, Liu Q, et al. Enhancing the tumor penetration of multiarm polymers by collagenase modification. Biomater Sci. 2024;12:2302–11. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3BM02123H.

Google Scholar

Xu F, Huang X, Wang Y, Zhou S. A size-changeable collagenase-modified nanoscavenger for increasing penetration and retention of nanomedicine in deep tumor tissue. Adv Mater. 2020;32:1906745. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201906745.

Google Scholar

Wang J, Wu Q, Wang Y, Xiang L, Feng J, Zhou Z, et al. Collagenase-loaded pH-sensitive nanocarriers efficiently remodeled tumor stroma matrixes and improved the enrichment of nanomedicines. Nanoscale. 2021;13:9402–14. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NR00950H.

Google Scholar

Liu Q, Wang L, Su Y, Dong W, Wang H, Liu Y, et al. Ultrahigh Enzyme Loading Metal-Organic Frameworks for Deep Tissue Pancreatic Cancer Photoimmunotherapy. Small. 2024;20:e2305131. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202305131.

Google Scholar

Abucafy MP, Galvao Frem RC, Polinario G, Pavan FR, Zhao H, Mielcarek A, et al. MIL-100(Fe) sub-micrometric capsules as a dual drug delivery system. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:7670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23147670.

Google Scholar

Oh JY, Seu M-S, Barui AK, Ok HW, Kim D, Choi E, et al. A multifunctional protein pre-coated metal–organic framework for targeted delivery with deep tissue penetration. Nanoscale. 2024;16:14748–56. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NR02345E.

Google Scholar

Deng B, Huang R, Liang R, Fei Y, Luo Q, Song G. Design and evaluation of collagenase-loaded nanoparticles for mechanical intervention of orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma in rat model. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;285:138311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.138311.

Google Scholar

Li J, Gong C, Chen X, Guo H, Tai Z, Ding N, et al. Biomimetic liposomal nanozymes improve breast cancer chemotherapy with enhanced penetration and alleviated hypoxia. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-01874-7.

Google Scholar

Luo J, Cao J, Ma G, Wang X, Sun Y, Zhang C, et al. Collagenase-loaded H-TiO2 nanoparticles enhance ultrasound imaging-guided sonodynamic therapy in a pancreatic carcinoma xenograft model via digesting stromal barriers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14:40535–45. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c08951.

Google Scholar

Maksoudian C, Izci M, Salembier R, Gilabert IP, Gonçalves FR, Luci CR, et al. Gold nanoparticle delivery to solid tumors by macrophage depletion, hypoxia inhibition, and collagen degradation. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2023;6:7605–18. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.3c00780.

Google Scholar

Murty S, Gilliland T, Qiao P, Tabtieng T, Higbee E, Al ZA, et al. Nanoparticles Functionalized with Collagenase Exhibit Improved Tumor Accumulation in a Murine Xenograft Model. Part Part Syst Charact. 2014;31:1307–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppsc.201400169.

Google Scholar

Yang X-Y, Zhang J-G, Zhou Q-M, Yu J-N, Lu Y-F, Wang X-J, et al. Extracellular matrix modulating enzyme functionalized biomimetic Au nanoplatform-mediated enhanced tumor penetration and synergistic antitumor therapy for pancreatic cancer. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20:524. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01738-6.

Google Scholar

Pan A, Zhaoyang W, Binlong C, Wenbing D, Hua Z, Bing H, et al. Localized co-delivery of collagenase and trastuzumab by thermosensitive hydrogels for enhanced antitumor efficacy in human breast xenograft. Drug Deliv. 2018;25:1495–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2018.1474971.

Google Scholar

Corder RD, Gadi SV, Vachieri RB, Jayes FL, Cullen JM, Khan SA, et al. Using rheology to quantify the effects of localized collagenase treatments on uterine fibroid digestion. Acta Biomater. 2021;134:443–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2021.08.003.

Google Scholar

Chen Y, Fan Z, Xu W, Zhu Z, Tan Z, Hu Y, et al. An injectable nanocomposite hydrogel with deep penetration ability for enhanced photothermal and chemotherapy. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2025;685:268–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2025.01.146.

Google Scholar

Yang C, Liao X, Zhou K, Yao Y, He X, Zhong W, et al. Multifunctional nanoparticles and collagenase dual loaded thermosensitive hydrogel system for enhanced tumor-penetration, reversed immune suppression and photodynamic-immunotherapy. Bioact Mater. 2025;48:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.02.014.

Google Scholar

Jansen CA, Cruijsen CWA, de Ruiter T, Nanlohy N, Willems N, Janssens-Korpela P, et al. Regulated expression of the inhibitory receptor LAIR-1 on human peripheral T cells during T cell activation and differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:914–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200636678.

Google Scholar

Kohli AG, Kivimäe S, Tiffany MR, Szoka FC. Improving the distribution of Doxil® in the tumor matrix by depletion of tumor hyaluronan. J Control Release. 2014;191:105–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.019.

Google Scholar

Kohli AG, Kierstead PH, Venditto VJ, Walsh CL, Szoka FC. Designer lipids for drug delivery: from heads to tails. J Control Release. 2014;190:274–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.04.047.

Google Scholar

Rezvantalab S, Drude NI, Moraveji MK, Güvener N, Koons EK, Shi Y, et al. PLGA-based nanoparticles in cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01260.

Google Scholar

Narmani A, Jahedi R, Bakhshian-Dehkordi E, Ganji S, Nemati M, Ghahramani-Asl R, et al. Biomedical applications of PLGA nanoparticles in nanomedicine: advances in drug delivery systems and cancer therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2023;20:937–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425247.2023.2223941.

Google Scholar

Kalyane D, Raval N, Maheshwari R, Tambe V, Kalia K, Tekade RK. Employment of enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR): nanoparticle-based precision tools for targeting of therapeutic and diagnostic agent in cancer. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;98:1252–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.01.066.

Google Scholar

Li B, Wen H-M, Cui Y, Zhou W, Qian G, Chen B. Emerging multifunctional metal-organic framework materials. Adv Mater. 2016;28:8819–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201601133.

Google Scholar

Bétard A, Fischer RA. Metal-organic framework thin films: from fundamentals to applications. Chem Rev. 2012;112:1055–83. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr200167v.

Google Scholar

Zhang Q, Kuang G, Li W, Wang J, Ren H, Zhao Y. Stimuli-responsive gene delivery nanocarriers for cancer therapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023;15:44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01018-4.

Google Scholar

Li Y, Dong H, Wang K, Shi D, Zhang X, Zhuo R. Stimulus-responsive polymeric nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Sci China Chem. 2010;53:447–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11426-010-0101-4.

Google Scholar

Mi P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery, tumor imaging, therapy and theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10:4557–88. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.38069.

Google Scholar

Hajebi S, Rabiee N, Bagherzadeh M, Ahmadi S, Rabiee M, Roghani-Mamaqani H, et al. Stimulus-responsive polymeric nanogels as smart drug delivery systems. Acta Biomater. 2019;92:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.018.

Google Scholar

Wei D, Sun Y, Zhu H, Fu Q. Stimuli-responsive polymer-based nanosystems for cancer theranostics. ACS Nano. 2023;17:23223–61. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c06019.

Google Scholar

Zou M, Shen C, Peng W, Zhang L, Liu W, Lv Y. A biomimetic nanoplatform with mechano-metabolic microenvironment and hypoxic microenvironment programming ability for enhanced chemo-immunotherapy. Chem Eng J. 2025;513:163088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2025.163088.

Google Scholar

Kuhn SJ, Finch SK, Hallahan DE, Giorgio TD. Proteolytic surface functionalization enhances in vitro magnetic nanoparticle mobility through extracellular matrix. Nano Lett. 2006;6:306–12. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl052241g.

Google Scholar

Mauro N, Scialabba C, Puleio R, Varvara P, Licciardi M, Cavalaro G, et al. SPIONs embedded in polyamino acid nanogels to synergistically treat tumor microenvironment and breast cancer cells. Int J Pharm. 2019;555:207–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.046.

Google Scholar

Yin T, Chen H, Ma A, Pan H, Chen Z, Tang X, et al. Cleavable collagenase-assistant nanosonosensitizer for tumor penetration and sonodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2023;293:121992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121992.

Google Scholar

Sun R, Zhang Y, Piao Y, Xiang J, Shao S, Zhou Q, et al. Dual enzyme-responsive polymer-drug conjugates induce diverse cells mutual transcytosis to achieve deep pancreatic tumor penetration. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202506038.

Google Scholar

LeBeau AM, Brennen WN, Aggarwal S, Denmeade SR. Targeting the cancer stroma with a fibroblast activation protein-activated promelittin protoxin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1378–86. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1170.

Google Scholar

Brennen WN, Rosen DM, Wang H, Isaacs JT, Denmeade SR. Targeting carcinoma-associated fibroblasts within the tumor stroma with a fibroblast activation protein-activated prodrug. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1320–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djs336.

Google Scholar

Zana A, Galbiati A, Gilardoni E, Bocci M, Millul J, Sturm T, et al. Fibroblast activation protein triggers release of drug payload from non-internalizing small molecule drug conjugates in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:5440–54. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-1788.

Google Scholar

Li Z, Mo F, Guo K, Ren S, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al. Nanodrug-bacteria conjugates-mediated oncogenic collagen depletion enhances immune checkpoint blockade therapy against pancreatic cancer. Med. 2024;5:348-367.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2024.02.012.

Google Scholar

Qi L, Duan B-W, Wang H, Liu Y-J, Han H, Han M-M, et al. Reactive oxygen species-responsive nanoparticles toward extracellular matrix normalization for pancreatic fibrosis regression. Adv Sci. 2024;11:2401254. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202401254.

Google Scholar

Zhou D, Duan Z, Li Z, Ge F, Wei R, Kong L. The significance of glycolysis in tumor progression and its relationship with the tumor microenvironment. Front Pharmacol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1091779.

Google Scholar

Abaza M, Luqmani YA. The influence of pH and hypoxia on tumor metastasis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2013;13:1229–42. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737140.2013.843455.

Google Scholar

Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:325–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29.

Google Scholar

Jain RK. Antiangiogenesis strategies revisited: from starving tumors to alleviating hypoxia. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(5):605–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.006.

Google Scholar

Zhang X, Lin Y, Gillies RJ. Tumor pH and its measurement. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1167–70. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.109.068981.

Google Scholar

Gilkes DM, Semenza GL, Wirtz D. Hypoxia and the extracellular matrix: drivers of tumour metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:430–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3726.

Google Scholar

Ji F, Wang Y, Qiu L, Li S, Zhu J, Liang Z, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor 1α-mediated LOX expression correlates with migration and invasion in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1578–88. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1878.

Google Scholar

Januzzi JL, Garasic JM, Kasner SE, McDonald V, Petrie MC, Seltzer J, et al. Retrospective analysis of arterial occlusive events in the PACE trial by an independent adjudication committee. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01221-z.

Google Scholar

Fais S, Venturi G, Gatenby B. Microenvironmental acidosis in carcinogenesis and metastases: new strategies in prevention and therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014;33:1095–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-014-9531-3.

Google Scholar

Lee S-H, McIntyre D, Honess D, Hulikova A, Pacheco-Torres J, Cerdán S, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX is a pH-stat that sets an acidic tumour extracellular pH in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2018;119:622–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0216-5.

Google Scholar

Büscheck F, Fraune C, Simon R, Kluth M, Hube-Magg C, Möller-Koop C, et al. Aberrant expression of membranous carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) is associated with unfavorable disease course in papillary and clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2018;36:531.e19-531.e25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.08.015.

Google Scholar

Panisova E, Kery M, Sedlakova O, Brisson L, Debreova M, Sboarina M, et al. Lactate stimulates CA IX expression in normoxic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:77819–35. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.20836.

Google Scholar

Vaupel P, Multhoff G. Fatal Alliance of Hypoxia-/HIF-1α-Driven Microenvironmental Traits Promoting Cancer Progression. Oxyg Transp Tissue XLI. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34461-0_21.

Google Scholar

Gonzalez-Avila G, Sommer B, Flores-Soto E, Aquino-Galvez A. Hypoxic effects on matrix metalloproteinases’ expression in the tumor microenvironment and therapeutic perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:16887. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316887.

Google Scholar

Springer M, Burakgazi ZA, Domukhovska A, Nafchi B, Beary MC, Acquisto A, et al. HIF-1α-mediated disruption of cellular junctions: the impact of hypoxia on the tumor microenvironment and invasion. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:5101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26115101.

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, Zhai Z, Duan J, Wang X, Zhong J, Wu L, et al. Lactate: the mediator of metabolism and immunosuppression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.901495.

Google Scholar

Zhou Y, Lou J, Tian Y, Ding J, Wang X, Tang B. How lactate affects immune strategies in lymphoma. Front Mol Biosci. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2024.1480884.

Google Scholar

Rahman MA, Yadab MK, Ali MM. Emerging role of extracellular pH in tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target for cancer immunotherapy. Cells. 2024;13:1924. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13221924.

Google Scholar

Saadat M, Mostafaei F, Mahdinloo S, Abdi M, Zahednezhad F, Zakeri-Milani P, et al. Drug delivery of pH-sensitive nanoparticles into the liver cancer cells. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;63:102557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102557.

Google Scholar

Lim E-K, Chung BH, Chung SJ. Recent advances in pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles for smart drug delivery in cancer therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19:300–17. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450117666160602202339.

Google Scholar

Zhang J, Zheng Y, Xie X, Wang L, Su Z, Wang Y, et al. Cleavable multifunctional targeting mixed micelles with sequential pH-triggered TAT peptide activation for improved antihepatocellular carcinoma efficacy. Mol Pharm. 2017;14:3644–59. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00404.

Google Scholar

Zhang C, An T, Wang D, Wan G, Zhang M, Wang H, et al. Stepwise pH-responsive nanoparticles containing charge-reversible pullulan-based shells and poly(β-amino ester)/poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) cores as carriers of anticancer drugs for combination therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma. J Control Release. 2016;226:193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.030.

Google Scholar

Zheng S, Wang J, Ding N, Chen W, Chen H, Xue M, et al. Prodrug polymeric micelles integrating cancer-associated fibroblasts deactivation and synergistic chemotherapy for gastric cancer. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-021-01127-5.

Google Scholar

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles. facile surface functionalization and versatile biomedical applications in oncology. Acta Biomater. 2020;116:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2020.09.009.

Google Scholar

Narayan R, Nayak UY, Raichur AM, Garg S. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: a comprehensive review on synthesis and recent advances. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10:118. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10030118.

Google Scholar

Gu J, Su S, Zhu M, Li Y, Zhao W, Duan Y, et al. Targeted doxorubicin delivery to liver cancer cells by PEGylated mesoporous silica nanoparticles with a pH-dependent release profile. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;161:160–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.05.035.

Google Scholar

Li M, Zhao G, Su W-K, Shuai Q. Enzyme-responsive nanoparticles for anti-tumor drug delivery. Front Chem. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2020.00647.

Google Scholar

Shahriari M, Zahiri M, Abnous K, Taghdisi SM, Ramezani M, Alibolandi M. Enzyme responsive drug delivery systems in cancer treatment. J Control Release. 2019;308:172–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.07.004.

Google Scholar

Kuang T, Liu Y, Gong T, Peng X, Hu X, Yu Z. Enzyme-responsive nanoparticles for anticancer drug delivery. Curr Nanosci. 2015;12:38–46. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573413711666150624170518.

Google Scholar

Zhao X, Wang T, Liu W, Wang C, Wang D, Shang T, et al. Multifunctional Au@IPN-pNIPAAm nanogels for cancer cell imaging and combined chemo-photothermal treatment. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:7240–7. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1JM10277J.

Google Scholar

Shang T, Wang C, Ren L, Tian X, Li D, Ke X, et al. Synthesis and characterization of NIR-responsive Aurod@pNIPAAm-PEGMA nanogels as vehicles for delivery of photodynamic therapy agents. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2013;8:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1556-276X-8-4.

Google Scholar

Heskins M, Guillet JE. Solution properties of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). Journal of Macromolecular Science: Part A. 1968;2:1441–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10601326808051910.

Google Scholar

Tauer K, Gau D, Schulze S, Völkel A, Dimova R. Thermal property changes of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) microgel particles and block copolymers. Colloid Polym Sci. 2009;287:299–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00396-008-1984-x.

Google Scholar

Van Durme K, Van Assche G, Van Mele B. Kinetics of demixing and remixing in poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)/water studied by modulated temperature DSC. Macromolecules. 2004;37:9596–605. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma048472b.

Google Scholar

Sung B, Kim C, Kim M-H. Biodegradable colloidal microgels with tunable thermosensitive volume phase transitions for controllable drug delivery. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;450:26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2015.02.068.

Google Scholar

Materón EM, Miyazaki CM, Carr O, Joshi N, Picciani PHS, Dalmaschio CJ, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical applications: a review. Applied Surface Science Advances. 2021;6:100163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100163.

Google Scholar

Rezaei B, Yari P, Sanders SM, Wang H, Chugh VK, Liang S, et al. Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Review on Synthesis, Characterization, Functionalization, and Biomedical Applications. Small. 2024;20:e2304848. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202304848.

Google Scholar

Zewail MB, Yang G, Fan Y, Hui Y, Zhao C-X, Liu Y. Cell membrane-coated lipid nanoparticles for drug delivery. Aggregate. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1002/agt2.70054.

Google Scholar

Alimohammadvand S, Kaveh Zenjanab M, Mashinchian M, Shayegh J, Jahanban-Esfahlan R. Recent advances in biomimetic cell membrane–camouflaged nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;177:116951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116951.

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Li C, Zhou Z, Lei H, Liu M, et al. Advances in cell membrane-based biomimetic nanodelivery systems for natural products. Drug Deliv. 2024;31:2361169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2024.2361169.

Google Scholar

Li B, Fei W, Lijuan G, Qing H, Yuxin Y, Chen H. The Potential of Biomimetic Nanoparticles for Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery. Nanomedicine. 2018;13:2099–118. https://doi.org/10.2217/nnm-2018-0017.

Google Scholar

Tan A, Rajadas J, Seifalian AM. Exosomes as nano-theranostic delivery platforms for gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:357–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2012.06.014.

Google Scholar

Sun D, Zhuang X, Zhang S, Deng Z-B, Grizzle W, Miller D, et al. Exosomes are endogenous nanoparticles that can deliver biological information between cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:342–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.002.

Google Scholar

Shi Y, Zhang J, Li Y, Feng C, Shao C, Shi Y, et al. Engineered mesenchymal stem/stromal cells against cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16:113. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-07443-0.

Google Scholar

Minev T, Balbuena S, Gill JM, Marincola FM, Kesari S, Lin F. Mesenchymal stem cells – the secret agents of cancer immunotherapy: promises, challenges, and surprising twists. Oncotarget. 2024;15:793–805. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.28672.

Google Scholar

Pegtel DM, Gould SJ. Exosomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2019;88:487–514. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111902.

Google Scholar

Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1907–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006.

Google Scholar

Freitas C, Sousa C, Machado F, Serino M, Santos V, Cruz-Martins N, et al. The role of liquid biopsy in early diagnosis of lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.634316.

Google Scholar

Baig MS, Roy A, Rajpoot S, Liu D, Savai R, Banerjee S, et al. Tumor-derived exosomes in the regulation of macrophage polarization. Inflamm Res. 2020;69:435–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-020-01318-0.

Google Scholar

Long L, Zhang X, Bai J, Li Y, Wang X, Zhou Y.

Tissue-specific and exosomal miRNAs in lung cancer radiotherapy: from regulatory mechanisms to clinical implications

. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:4413–24. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S198966.

Google Scholar

Hakulinen J, Sankkila L, Sugiyama N, Lehti K, Keski-Oja J. Secretion of active membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-14) into extracellular space in microvesicular exosomes. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:1211–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.21923.

Google Scholar

Sanderson RD, Bandari SK, Vlodavsky I. Proteases and glycosidases on the surface of exosomes: newly discovered mechanisms for extracellular remodeling. Matrix Biol. 2019;75:160–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2017.10.007.

Google Scholar

Li T, Yan Y, Wang B, Qian H, Zhang X, Shen L, et al. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate liver fibrosis. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:845–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2012.0395.

Google Scholar

Zhao B, Shi X, Feng D, Han J, Hu D. MicroRNA let-7d attenuates hypertrophic scar fibrosis through modulation of iron metabolism by reducing DMT1 expression. J Mol Histol. 2023;54:77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10735-023-10113-0.

Google Scholar

Yin F, Wang W-Y, Mao L-C, Cai Q-Q, Jiang W-H. Effect of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells transfected with HGF on TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway in carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis rats. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29:1395–406. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2020.0060.

Google Scholar

Yang J, Hu H, Zhang S, Jiang L, Cheng Y, Xie H, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes alleviate pulmonary fibrosis in mice by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020;40:988–94. https://doi.org/10.2122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.07.11.

Google Scholar

Baglio SR, Pegtel DM, Baldini N. Mesenchymal stem cell secreted vesicles provide novel opportunities in (stem) cell-free therapy. Front Physiol. 2012;3:359. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2012.00359.

Google Scholar

Lou G, Chen Z, Zheng M, Liu Y. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a new therapeutic strategy for liver diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e346. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.63.

Google Scholar

Li J, Ghazwani M, Zhang Y, Lu J, Li J, Fan J, et al. MiR-122 regulates collagen production via targeting hepatic stellate cells and suppressing P4HA1 expression. J Hepatol. 2013;58:522–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.011.

Google Scholar

Milosavljevic N, Gazdic M, Simovic Markovic B, Arsenijevic A, Nurkovic J, Dolicanin Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate liver fibrosis by suppressing Th17 cells – an experimental study. Transplant Int. 2018;31(1):102–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.13023.

Google Scholar

Dooley S, ten Dijke P. TGF-β in progression of liver disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:245–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-011-1246-y.

Google Scholar

Brenner DA. Transforming growth factor B and hepatic fibrosis: cause or effect? Hepatology. 1991;14:740–2.

Google Scholar

Arias M, Lahme B, Van de Leur E, Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Adenoviral delivery of an antisense RNA complementary to the 3’ coding sequence of transforming growth factor-beta1 inhibits fibrogenic activities of hepatic stellate cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2002;13:265–73.

Google Scholar

Liu X, Wang H, Yang M, Hou Y, Chen Y, Bie P. Exosomal miR-29b from cancer-associated fibroblasts inhibits the migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Transl Cancer Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2020.02.68.

Google Scholar

Fang J-H, Zhou H-C, Zeng C, Yang J, Liu Y, Huang X, et al. Microrna-29b suppresses tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis by regulating matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression. Hepatology. 2011;54:1729–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24577.

Google Scholar

Forbes SJ, Gupta S, Dhawan A. Cell therapy for liver disease: From liver transplantation to cell factory. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S157–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.040.

Google Scholar

Trombino S, Servidio C, Curcio F, Cassano R. Strategies for hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel design in drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11:407. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics11080407.

Google Scholar

Fan S, Liu Q, Dong J, Ai X, Li J, Huang W, et al. In situ forming an injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogel for drug delivery and synergistic tumor therapy. Heliyon. 2024;10:e32135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32135.

Google Scholar

Kim JH, Moon MJ, Kim DY, Heo SH, Jeong YY. Hyaluronic acid-based nanomaterials for cancer therapy. Polymers. 2018;10:1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10101133.

Google Scholar

Qin Y, Geng X, Sun Y, Zhao Y, Chai W, Wang X, et al. Ultrasound nanotheranostics: toward precision medicine. J Control Release. 2023;353:105–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.11.021.

Google Scholar

Son S, Kim JH, Wang X, Zhang C, Yoon SA, Shin J, et al. Multifunctional sonosensitizers in sonodynamic cancer therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49:3244–61. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CS00648F.

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yang H, Yu L, Xu Y, Sharma A, et al. Advanced biotechnology-assisted precise sonodynamic therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50:11227–48. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1CS00403D.

Google Scholar

Continuous inertial cavitation evokes massive ROS for reinforcing sonodynamic therapy and immunogenic cell death against breast carcinoma. Nano Today. 2021;36:101009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2020.101009

Wang H, Guo J, Lin W, Fu Z, Ji X, Yu B, et al. Open-shell nanosensitizers for glutathione responsive cancer sonodynamic therapy. Adv Mater. 2022;34:2110283. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202110283.

Google Scholar

Zheng X, Goins BA, Cameron IL, Santoyo C, Bao A, Frohlich VC, et al. Ultrasound-guided intratumoral administration of collagenase-2 improved liposome drug accumulation in solid tumor xenografts. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:173–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-010-1305-1.

Google Scholar

Brennen WN, Isaacs JT, Denmeade SR. Rationale behind targeting fibroblast activation protein-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts as a novel chemotherapeutic strategy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:257–66. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0340.

Google Scholar

Koczorowska Mm, Tholen S, Bucher F, Lutz L, Kizhakkedathu Jn, De Wever O, et al. Fibroblast activation protein-α, a stromal cell surface protease, shapes key features of cancer associated fibroblasts through proteome and degradome alterations. Mol Oncol. 2016;10:40–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2015.08.001.

Google Scholar

Nissen NI, Karsdal M, Willumsen N. Collagens and cancer associated fibroblasts in the reactive stroma and its relation to cancer biology. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-019-1110-6.

Google Scholar

Levy MT, McCaughan GW, Abbott CA, Park JE, Cunningham AM, Müller E, et al. Fibroblast activation protein: a cell surface dipeptidyl peptidase and gelatinase expressed by stellate cells at the tissue remodelling interface in human cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1768–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510290631.

Google Scholar

Meng S, Hara T, Miura Y, Ishii H. Fibroblast activation protein constitutes a novel target of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in solid tumors. Cancer Sci. 2024;115:3532–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.16285.

Google Scholar

Garin-Chesa P, Old LJ, Rettig WJ. Cell surface glycoprotein of reactive stromal fibroblasts as a potential antibody target in human epithelial cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7235–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.87.18.7235.

Google Scholar

Rettig WJ, Garin-Chesa P, Healey JH, Su SL, Ozer HL, Schwab M, et al. Regulation and heteromeric structure of the fibroblast activation protein in normal and transformed cells of mesenchymal and neuroectodermal origin. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3327–35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8391923

Brennen WN, Thorek JDL, Jiang W, Krueger TE, Antony L, Denmeade SR, et al. Overcoming stromal barriers to immuno-oncological responses via fibroblast activation protein-targeted therapy. Immunotherapy. 2021;13:155–75. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2020-0066.

Google Scholar

Fang J, Xiao L, Joo K-I, Liu Y, Zhang C, Liu S, et al. A potent immunotoxin targeting fibroblast activation protein for treatment of breast cancer in mice. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1013–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29831.

Google Scholar

Fang J, Hu B, Li S, Zhang C, Liu Y, Wang P. A multi-antigen vaccine in combination with an immunotoxin targeting tumor-associated fibroblast for treating murine melanoma. Mol Ther. 2016;3:16007. https://doi.org/10.1038/mto.2016.7.

Google Scholar

Xia Q, Zhang F-F, Geng F, Liu C-L, Xu P, Lu Z-Z, et al. Anti-tumor effects of DNA vaccine targeting human fibroblast activation protein α by producing specific immune responses and altering tumor microenvironment in the 4T1 murine breast cancer model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:613–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-016-1827-4.

Google Scholar

Duperret EK, Trautz A, Ammons D, Perales-Puchalt A, Wise MC, Yan J, et al. Alteration of the tumor stroma using a consensus DNA vaccine targeting fibroblast activation protein (FAP) synergizes with antitumor vaccine therapy in mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1190–201. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2033.

Google Scholar

Teng C, Zhang B, Yuan Z, Kuang Z, Chai Z, Ren L, et al. Fibroblast activation protein-α-adaptive micelles deliver anti-cancer drugs and reprogram stroma fibrosis. Nanoscale. 2020;12:23756–67. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0nr04465b.

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, Zhou J, Chen X, Li Z, Gu L, Pan D, et al. Modulating tumor-stromal crosstalk via a redox-responsive nanomedicine for combination tumor therapy. J Control Release. 2023;356:525–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.03.015.

Google Scholar

Zhou S, Zhen Z, Paschall AV, Xue L, Yang X, Bebin Blackwell A-G, et al. FAP-targeted photodynamic therapy mediated by ferritin nanoparticles elicits an immune response against cancer cells and cancer associated fibroblasts. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31:2007017. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202007017.

Google Scholar

Gao C, Jian C, Wang L, Liu Y, Xiong Y, Wu T, et al. FAP-targeting biomimetic nanosystem to restore the activated cancer-associated fibroblasts to quiescent state for breast cancer radiotherapy. Int J Pharm. 2025;670:125190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2025.125190.

Google Scholar

Cappell KM, Kochenderfer JN. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:359–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00754-1.

Google Scholar

Rao S, Kiick KL. Recent advances in extracellular matrix-inspired nanocarriers. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425247.2025.2519809.

Google Scholar

Peng L, Sferruzza G, Yang L, Zhou L, Chen S. CAR-T and CAR-NK as cellular cancer immunotherapy for solid tumors. Cell Mol Immunol. 2024;21(10):1089–108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-024-01207-0.

Google Scholar

Schuberth PC, Hagedorn C, Jensen SM, Gulati P, van den Broek M, Mischo A, et al. Treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma by fibroblast activation protein-specific re-directed T cells. J Transl Med. 2013;11:187. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-11-187.

Google Scholar

Wang L-CS, Lo A, Scholler J, Sun J, Majumdar RS, Kapoor V, et al. Targeting fibroblast activation protein in tumor stroma with chimeric antigen receptor T cells can inhibit tumor growth and augment host immunity without severe toxicity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:154–66. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0027.

Google Scholar

Rodriguez-Garcia A, Palazon A, Noguera-Ortega E, Powell DJ, Guedan S. Car-T cells hit the tumor microenvironment: strategies to overcome tumor escape. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1109. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01109.

Google Scholar

Roberts EW, Deonarine A, Jones JO, Denton AE, Feig C, Lyons SK, et al. Depletion of stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-α from skeletal muscle and bone marrow results in cachexia and anemia. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1137–51. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20122344.

Google Scholar

Tran E, Chinnasamy D, Yu Z, Morgan RA, Lee C-CR, Restifo NP, et al. Immune targeting of fibroblast activation protein triggers recognition of multipotent bone marrow stromal cells and cachexia. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1125–35. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20130110.

Google Scholar

Loeffler M, Krüger JA, Niethammer AG, Reisfeld RA. Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Investig. 2006;116:1955–62. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI26532.

Google Scholar

Lee J, Fassnacht M, Nair S, Boczkowski D, Gilboa E. Tumor immunotherapy targeting fibroblast activation protein, a product expressed in tumor-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11156–63. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2805.

Google Scholar

Wen Y, Wang C-T, Ma T-T, Li Z-Y, Zhou L-N, Mu B, et al. Immunotherapy targeting fibroblast activation protein inhibits tumor growth and increases survival in a murine colon cancer model. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2325–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01695.x.

Google Scholar

Kakarla S, Chow KKH, Mata M, Shaffer DR, Song X-T, Wu M-F, et al. Antitumor effects of chimeric receptor engineered human T cells directed to tumor stroma. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1611–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2013.110.

Google Scholar

Wang W, Hu K, Xue J, Chen J, Du X, Zhao T, et al. In vivo FAP-CAR macrophages enhance chemotherapy and immunotherapy against pancreatic cancer by removing the fibrosis barrier. J Control Release. 2025;384:113888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2025.113888.

Google Scholar

Ruixin S, Yifan L, Yansha S, Min Z, Yiwei D, Xiaoli H, et al. Dual targeting chimeric antigen receptor cells enhance antitumour activity by overcoming T cell exhaustion in pancreatic cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2024;181:4628–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.16505.

Google Scholar

Augsten M. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts as Another Polarized Cell Type of the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Oncol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2014.00062.

Google Scholar

Yoshida GJ. Regulation of heterogeneous cancer-associated fibroblasts: the molecular pathology of activated signaling pathways. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-020-01611-0.

Google Scholar

Chen C-Y, Yang S-H, Chang P-Y, Chen S-F, Nieh S, Huang W-Y, et al. Cancer-associated-fibroblast-mediated paracrine and autocrine SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling promotes stemness and aggressiveness of colorectal cancers. Cells. 2024;13:1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13161334.

Google Scholar

Tan H-X, Gong W-Z, Zhou K, Xiao Z-G, Hou F-T, Huang T, et al. CXCR4/TGF-β1 mediated hepatic stellate cells differentiation into carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and promoted liver metastasis of colon cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2020;21:258–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2019.1685157.

Google Scholar

Sugihara H, Ishimoto T, Yasuda T, Izumi D, Eto K, Sawayama H, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived CXCL12 causes tumor progression in adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Med Oncol. 2015;32:168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-015-0618-7.

Google Scholar

Terai S, Fushida S, Tsukada T, Kinoshita J, Oyama K, Okamoto K. Bone marrow derived “fibrocytes” contribute to tumor proliferation and fibrosis in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:306–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0380-0.

Google Scholar

Ullah A, Wang K, Wu P, Oupicky D, Sun M.

CXCR4-targeted liposomal mediated co-delivery of pirfenidone and AMD3100 for the treatment of TGFβ-induced HSC-T6 cells activation

. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;Volume 14:2927–44. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S171280.

Google Scholar

Chen Y, Huang Y, Reiberger T, Duyverman AM, Huang P, Samuel R, et al. Differential effects of sorafenib on liver versus tumor fibrosis mediated by stromal-derived factor 1 alpha/C-X-C receptor type 4 axis and myeloid differentiation antigen–positive myeloid cell infiltration in mice. Hepatology. 2014;59:1435–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26790.

Google Scholar

Thuya WL, Cao Y, Ho PC-L, Wong AL-A, Wang L, Zhou J, et al. Insights into IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025;85:26–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2025.01.003.

Google Scholar

Li Y, Zhao J, Yin Y, Li K, Zhang C, Zheng Y. The role of IL-6 in fibrotic diseases: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:5405–14. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.75876.

Google Scholar

Montero P, Milara J, Roger I, Cortijo J. Role of JAK/STAT in interstitial lung diseases; molecular and cellular mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126211.

Google Scholar

Cortés AA, Diaz RA, Hernández-Campo P, Gorrochategui J, Primo D, Robles A, et al. Ruxolitinib in combination with prednisone and nilotinib exhibit synergistic effects in human cells lines and primary cells from myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2019;104:937–46. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.201038.

Google Scholar

Han C, Wang L-J, Dong Z-Q, Wang P-Y, Lv Y-W, Wang D, et al. Nintedanib alleviates chronic pancreatitis by inhibiting the activation of pancreatic stellate cells via the JAK/STAT3 and ERK1/2 pathways. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:3644–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-08052-7.

Google Scholar

Avsharian LC, Loganathan S, Ebelt ND, Shalamzari AF, Rodarte Muñoz I, Manuel ER. Tumor-colonizing E. coli expressing both collagenase and hyaluronidase enhances therapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer models. Biomolecules. 2024;14:1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14111458.

Google Scholar

Pickup MW, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1243–53. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201439246.

Google Scholar

Handorf AM, Yaxian Z, Matthew AH, Li W-J. Tissue Stiffness Dictates Development, Homeostasis, and Disease Progression. Organogenesis. 2015;11:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476278.2015.1019687.

Google Scholar

Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044.

Google Scholar

Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010.

Google Scholar

Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ. Matrix density-induced mechanoregulation of breast cell phenotype, signaling and gene expression through a FAK–ERK linkage. Oncogene. 2009;28:4326–43. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2009.299.

Google Scholar

Morris BA, Burkel B, Ponik SM, Fan J, Condeelis JS, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al. Collagen matrix density drives the metabolic shift in breast cancer cells. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:146–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.10.012.

Google Scholar

Gunzer M, Schäfer A, Borgmann S, Grabbe S, Zänker KS, Bröcker E-B, et al. Antigen Presentation in Extracellular Matrix: Interactions of T Cells with Dendritic Cells Are Dynamic, Short Lived, and Sequential. Immunity. 2000;13:323–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00032-7.

Google Scholar

Dustin ML, de Fougerolles AR. Reprograming T cells: the role of extracellular matrix in coordination of T cell activation and migration. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:286–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00217-X.

Google Scholar

Dustin ML, Choudhuri K. Signaling and polarized communication across the T cell immunological synapse. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2016;32:303–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125330.

Google Scholar

Kuczek DE, Larsen AMH, Thorseth M-L, Carretta M, Kalvisa A, Siersbæk MS, et al. Collagen density regulates the activity of tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-019-0556-6.

Google Scholar

Rømer AMA, Thorseth M-L, Madsen DH. Immune modulatory properties of collagen in cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;12:791453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.791453.

Google Scholar

Nicolas-Boluda A, Vaquero J, Vimeux L, Guilbert T, Barrin S, Kantari-Mimoun C, et al. Tumor stiffening reversion through collagen crosslinking inhibition improves T cell migration and anti-PD-1 treatment. Elife. 2021. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.58688.

Google Scholar

Zhao Z, Li Q, Qu C, Jiang Z, Jia G, Lan G, et al. A collagenase nanogel backpack improves CAR-T cell therapy outcomes in pancreatic cancer. Nat Nanotechnol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-01924-1.

Google Scholar

Larsen AMH, Kuczek DE, Kalvisa A, Siersbæk MS, Thorseth M-L, Johansen AZ, et al. Collagen density modulates the immunosuppressive functions of macrophages. J Immunol. 2020;205:1461–72. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1900789.

Google Scholar

Peng DH, Rodriguez BL, Diao L, Chen L, Wang J, Byers LA, et al. Collagen promotes anti-PD-1/PD-L1 resistance in cancer through LAIR1-dependent CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4520. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18298-8.

Google Scholar

Xu L, Shanlong W, Jufeng L, Jie L, Li B. Cancer immunotherapy based on blocking immune suppression mediated by an immune modulator LAIR-1. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9:1740477. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2020.1740477.

Google Scholar

Ramos MIP, Tian L, de Ruiter EJ, Song C, Paucarmayta A, Singh A, et al. Cancer immunotherapy by NC410, a LAIR-2 Fc protein blocking human LAIR-collagen interaction. Elife. 2021;10:e62927. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62927.

Google Scholar

Piper M, Mueller AC, Karam SD. The interplay between cancer associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the context of radiation therapy. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59:754–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.23205.

Google Scholar

Oncogenic collagen I homotrimers from cancer cells bind to α3β1 integrin and impact tumor microbiome and immunity to promote pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:818–834.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2022.06.011

Dwyer AR, Truong TH, Ostrander JH, Lange CA. 90 years of progesterone: steroid receptors as MAPK signaling sensors in breast cancer: let the fates decide. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-19-0274.

Google Scholar

Lebbink RJ, de Ruiter T, Adelmeijer J, Brenkman AB, van Helvoort JM, Koch M, et al. Collagens are functional, high affinity ligands for the inhibitory immune receptor LAIR-1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1419–25. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20052554.

Google Scholar

A Study of PEGylated Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase in Combination With Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine Compared With Placebo Plus Nab-Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine in Participants With Hyaluronan-High Stage IV Previously Untreated Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02715804?cond=PDAC%20-%20Pancreatic%20Ductal%20Adenocarcinoma&intr=PEGPH20&rank=7. 2025.

Maneval DC, L. Caster C, Derunes C, Locke KW, Muhsin M, Sauter S, et al. Pegvorhyaluronidase alfa. Polymer-Protein Conjugates. Elsevier; 2020; 175–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64081-9.00009-7

Nagase H, Visse R, Murphy G. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:562–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.002.

Google Scholar

Bond MD, Van Wart HE. Characterization of the individual collagenases from Clostridium histolyticum. Biochemistry. 1984;23:3085–91. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00308a036.

Google Scholar

Mandl I, Zipper H, Ferguson LT. Clostridium histolyticum collagenase: its purification and properties. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1958;74:465–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(58)90017-1.

Google Scholar

Fágáin CÓ. Understanding and increasing protein stability. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). 1995;1252:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4838(95)00133-F.

Google Scholar

Tran S, DeGiovanni P-J, Piel B, Rai P. Cancer nanomedicine: a review of recent success in drug delivery. Clin Transl Med. 2017;6:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40169-017-0175-0.

Google Scholar

Raj S, Khurana S, Choudhari R, Kesari KK, Kamal MA, Garg N, et al. Specific targeting cancer cells with nanoparticles and drug delivery in cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2021;69:166–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.11.002.

Google Scholar

Foley CJ, Luo C, O’Callaghan K, Hinds PW, Covic L, Kuliopulos A. Matrix metalloprotease-1a promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24330–8. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.356303.

Google Scholar

Cao J, Chiarelli C, Kozarekar P, Adler HL. Membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase promotes human prostate cancer invasion and metastasis. Thromb Haemost. 2017;93:770–8. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH04-08-0555.

Google Scholar

Kudo Y, Iizuka S, Yoshida M, Tsunematsu T, Kondo T, Subarnbhesaj A, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) directly and indirectly promotes tumor angiogenesis*. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38716–28. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.373159.

Google Scholar

Radisky ES, Radisky DC. Matrix metalloproteinase-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15:201–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-010-9177-x.

Google Scholar

Eble JA, Niland S. The extracellular matrix in tumor progression and metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2019;36:171–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-019-09966-1.

Google Scholar

Bayer SV, Grither WR, Brenot A, Hwang PY, Barcus CE, Ernst M, et al. DDR2 controls breast tumor stiffness and metastasis by regulating integrin mediated mechanotransduction in CAFs. Elife. 2019. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.45508.

Google Scholar

Akinjiyan FA, Ibitoye Z, Zhao P, Shriver LP, Patti GJ, Longmore GD, et al. DDR2-regulated arginase activity in ovarian cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes collagen production and tumor progression. Oncogene. 2024;43:189–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-023-02884-3.

Google Scholar

Jung E, Kim TY, Han J, Lee KY, Shin SY. TLR2–EGR1 signaling axis modulates TGFβ1-induced differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024;736:150836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150836.

Google Scholar

Diehm YF, Jost Y, Kotsougiani-Fischer D, Haug V, Splinter M, Häring P, et al. The treatment of capsular contracture around breast implants induced by fractionated irradiation: the collagenase of the bacterium Clostridium histolyticum as a novel therapeutic approach. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2021;45:1273–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-020-01970-1.

Google Scholar

Alkasalias T, Moyano-Galceran L, Arsenian-Henriksson M, Lehti K. Fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment: shield or spear? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19051532.

Google Scholar

Høye AM, Erler JT. Structural ECM components in the premetastatic and metastatic niche. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;310:C955–67. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00326.2015.

Google Scholar

Mohan V, Das A, Sagi I. Emerging roles of ECM remodeling processes in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;62:192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.09.004.

Google Scholar

Okada M, Oba Y, Yamawaki H. Endostatin stimulates proliferation and migration of adult rat cardiac fibroblasts through PI3K/Akt pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;750:20–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.01.019.

Google Scholar

Favreau AJ, Vary CPH, Brooks PC, Sathyanarayana P. Cryptic collagen IV promotes cell migration and adhesion in myeloid leukemia. Cancer Med. 2014;3:265–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.203.

Google Scholar

Mierke CT. Extracellular matrix cues regulate mechanosensing and mechanotransduction of cancer cells. Cells. 2024;13:96. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13010096.

Google Scholar

Pankova D, Jiang Y, Chatzifrangkeskou M, Vendrell I, Buzzelli J, Ryan A, et al. RASSF 1A controls tissue stiffness and cancer stem-like cells in lung adenocarcinoma. EMBO J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.5252/embj.2018100532.

Google Scholar

Plasmodium falciparum strains 3D7, NF54-E (MRA-1000), Dd2, and Dd2-GNF156, which were obtained from Bei Resources (USA), were maintained in culture as previously…

Moss spores that spent nearly nine months outside the International Space Station have continued to reproduce after returning to Earth, surprising researchers and opening new possibilities for studying life in extreme environments.

The…