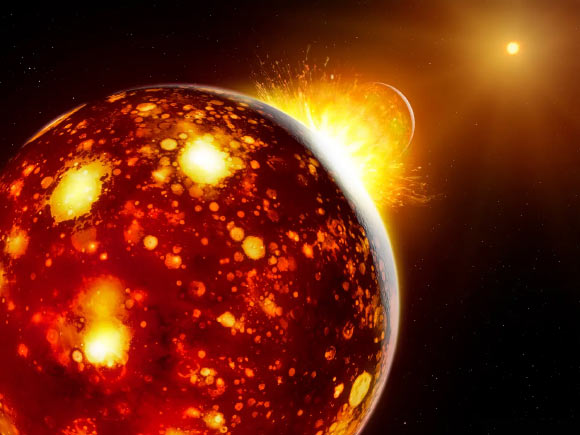

The Moon formed from a giant impact of the proto-Earth with the ancient protoplanet Theia. In a new study, a team of scientists from the United States, Germany, France and China measured iron isotopes in lunar samples, terrestrial rocks, and…

Author: admin

-

Chadwick Boseman’s widow reveals actor’s creative philosophy

At the Walk of Fame ceremony honoring her late husband on Thursday in Hollywood, Chadwick Boseman’s widow shared the underpinnings of the actor’s creative success.

Simone Ledward Boseman, who married him privately before his death on Aug….

Continue Reading

-

SEC SolarWinds Dismissal: Shifting Cyber Enforcement Risks

The outcome caps a long-running and closely watched legal dispute that began with sweeping fraud and controls allegations tied to SolarWinds’ statements about its cybersecurity practices and its disclosures following the breach of its flagship Orion software platform in 2020. The dismissal comes amid a broader recalibration of enforcement priorities in the new administration, including the SEC’s announcement earlier this year that it will focus on public issuer “fraudulent disclosure” relating to cybersecurity—signaling a pivot away from actions based on more nuanced allegations of disclosure deficiencies. The SEC’s decision to abandon the SolarWinds case altogether is the most pointed example yet of that shift.

The SEC’s dismissal may bring a sigh of relief to many companies and CISOs who were concerned about the chilling effect the case could have on the work of security teams to proactively identify vulnerabilities and gaps in cyber programs. However, public companies must still proceed carefully when making public statements about their security programs. In the wake of a cyber incident, any number of federal, state, or international regulators, as well as courts and litigants, may scrutinize and seize upon a company’s cybersecurity disclosures as evidence of negligence or worse. This includes the SEC, which, in late 2023, issued new requirements for companies to disclose material cyber risks and incidents to investors. Accordingly, effective governance around drafting and vetting cybersecurity statements and disclosures remains critical.

I. Dispute Background

The SolarWinds lawsuit arose out of the 2020 supply-chain attack, widely attributed to the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, in which the threat actors inserted malicious code into an Orion software update, allowing potential access to thousands of SolarWinds customers. Prior to and after its 2018 IPO, SolarWinds had published a “Security Statement” on its website describing its cybersecurity practices, including its password policies, access controls, secure development lifecycle practices, and use of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework. SolarWinds had also disclosed to investors that its systems were “vulnerable” to threats from nation-state actors. Once it discovered the attack in December 2020, SolarWinds filed a Form 8-K with the SEC and publicly disclosed the incident while continuing its investigation and remediation efforts.

In October 2023, the SEC brought an enforcement action against SolarWinds and Brown in federal court, alleging the defendants defrauded investors by overstating SolarWinds’ cybersecurity practices and understating known risks. First, the amended complaint alleged SolarWinds and Brown violated the Securities Act and Exchange Act by making materially false and misleading statements in the company’s Security Statement posted on its website, in SEC registration statements, in press releases, blog posts, and podcasts. Second, the complaint alleged that SolarWinds violated reporting provisions by filing materially misleading cybersecurity risk disclosures in pre-incident public filings, and by issuing an incomplete December 2020 Form 8-K in which SolarWinds presented its understanding of the attack. Third, the SEC alleged that SolarWinds failed to devise and maintain adequate internal accounting controls under Section 13(b)(2)(B) of the Exchange Act, and it further alleged that Brown aided and abetted these violations. Finally, the agency claimed SolarWinds violated the requirements under Rule 13a-15(a) to maintain proper disclosure controls and procedures to escalate incidents to management. This case marked the first time the SEC brought a cybersecurity enforcement action against an individual CISO, and the first time it asserted accounting control claims based on technical cybersecurity failings.

II. 2024 Partial Dismissal

On July 18, 2024, U.S. District Judge Paul A. Engelmayer of the Southern District of New York issued a 107 page opinion dismissing most of the SEC’s claims. The court rejected the claims alleging false and misleading statements made in press releases, blog posts, and podcasts, finding them to be only “non-actionable corporate puffery.” It also rejected the allegations concerning the post-incident disclosures, emphasizing that they must be read in context of an unfolding investigation and that the SEC’s arguments relied on the benefit of hindsight. The court dismissed the SEC’s novel internal accounting controls claims, holding that such controls are about assuring the integrity of the company’s financial transactions, not detecting or preventing cybersecurity deficiencies in source code or network environments. Finally, the court dismissed the Rule 13a 15(a) disclosure controls claim, finding that the existence of two misclassified incidents did not amount to “systemic deficiencies” in SolarWinds’ disclosure controls and procedures.

The only claims that were allowed to proceed concerned the representations in the website Security Statement about access controls and password protection policies. The court drew a line between “corporate puffery” and actionable statements and held that the Security Statement was publicly accessible and part of the “total mix of information” SolarWinds provided to the public, and that the SEC sufficiently pled SolarWinds’ practices materially diverged from its statements.

III. 2025 Summary Judgment Proceedings

Following the court’s 2024 ruling, SolarWinds and Brown moved for summary judgment in April 2025. Signaling another shift in SolarWinds’ favor, the SEC acknowledged in a Joint Statement of Undisputed Facts that, during the relevant period, SolarWinds did implement practices described in its Security Statement, including use of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework; role based access provisioning; enforcement of password complexity; and secure development lifecycle measures such as vulnerability testing, regression testing, penetration testing, and product security assessments.

IV. 2025 Settlement and Final Dismissal

On July 2, 2025, prior to any ruling on summary judgment, the SEC, SolarWinds, and Brown jointly notified Judge Engelmayer that they had reached a settlement in principle. The court stayed proceedings to allow the parties to finalize the settlement paperwork. The anticipated settlement, however, did not materialize. Instead, on November 20, 2025, the parties filed a Joint Stipulation to Dismiss, in which the SEC agreed to dismiss the remaining claims against SolarWinds and Brown with prejudice without any settlement conditions (other than a waiver of potential claims against the SEC and the United States arising from the litigation).

V. The Next Chapter: What to Take Away from SolarWinds

The dismissal indicates a shift in the SEC’s enforcement approach—one that narrows, but does not eliminate, risk for public companies. For now, it appears the Commission is moving toward a “back to basics” approach, focusing on egregious misstatements and material misrepresentations resulting in investor harm. Even as the SEC refocuses on more traditional fraud theories, companies remain exposed to liability and scrutiny across multiple fronts, including expanding and disparate regulatory regimes, as well as private litigation that mines public statements and incident reporting for inconsistencies or omissions.

1. Regulatory and litigation risk remains high

While the SEC may pare back enforcement, this does not mean that other regulators will follow suit. Sector-specific regulators and state regulators, for example, have been increasingly active in cyber enforcement and may fill the void. Global companies also face a growing array of international regulators that scrutinize cyber incidents with data privacy, critical infrastructure, and operational resilience impacts.

In addition to regulatory enforcement, private litigation remains active. Securities class actions are common following high profile cyber incidents, particularly when public disclosures are contested. Indeed, plaintiffs’ firms are quick to file derivative suits alleging oversight failures and consumer class actions under consumer protection laws are frequent when cyber incidents are made public.

Of course, courts and regulators evaluate these issues case by case. The record in SolarWinds turned on specific facts, many of which ended up more favorable to SolarWinds following discovery than the SEC had initially alleged. And while Judge Engelmayer agreed with several of SolarWinds’ key arguments related to its conduct and statements at issue, that is not to say that another court would reach the same outcome. One or two slightly different takes on the statements or actions that were in question could have swung the pendulum in the opposite direction.

Regardless of the outcome in this case, companies should continue to concentrate on the quality and accuracy of cybersecurity disclosures, the robustness of governance and controls supporting those disclosures, and the documentation that demonstrates reasonable, risk aligned practices. In particular, companies should ensure incident materiality determinations are well documented, cross channel communications are consistent, and governance processes tie public statements to verified technical facts.

2. Securities disclosure requirements have expanded

The disclosures at issue in SolarWinds took place before the SEC adopted its new rule on Cybersecurity Risk Management, Strategy, Governance, and Incident Disclosure by Public Companies (the “Cyber Rules”). Since December 2023, the Cyber Rules have imposed new requirements for timely Form 8 K reporting of material incidents and added detailed requirements for disclosures of cyber risk management and governance in annual reports. Companies should be diligent in ensuring that their disclosures and public statements made today are in line with what the company has put into place. Even if the SEC declines to bring an enforcement action based on alleged disclosure deficiencies where there is no investor harm, the new triggering requirements and the expanded disclosures under the Cyber Rules heighten the risk that those statements, or the failure to make those statements, will be used against companies by private litigants and other regulators.

3. Executives are not off the hook.

The SolarWinds case raised concerns that CISOs could be subject to a low bar for personal liability. With the dismissal, companies may wonder whether individual executive exposure for cyber failures remains a serious risk. While the threshold for individual CISO enforcement risk may now be higher in the securities context, senior leaders may still be targeted in cases involving alleged misrepresentations, negligence, or failures in oversight that result in consumer or market harm.

Indeed, the expectation environment for CISOs and other senior leaders continues to intensify. Regulators increasingly expect sophisticated boards and executive teams to focus not only on the existence of cybersecurity programs, but on their specificity, execution quality, and alignment with risk standards. This includes probing “ground truth” technical measures like vulnerability management, identity and access controls, incident response readiness, logging and monitoring sufficiency, and third party risk management—and assessing whether responsible individuals exercised appropriate oversight.

In short, while one case may reduce immediate headline risk, it may not meaningfully change the direction of the broader legal and regulatory landscape. Executives with cybersecurity oversight should continue to assume heightened scrutiny, ensure governance around risk prioritization and resourcing, and demonstrate reasonableness regarding technical controls and external statements.

4. Enforcement will vary by impact.

SEC enforcement is certainly not one-size-fits-all. Even given the SEC’s refocused priorities, enforcement could vary across companies and sectors. Factors such as inherent cyber risk, size, sophistication, and market impact may influence enforcement. Sectors that are more likely to suffer or inflict greater impact from significant operational disruptions, such as financial institutions, providers of pervasive technology services, or critical infrastructure, may be scrutinized more heavily. In other words, the greater the potential harm to shareholders or the market generally, the greater SEC scrutiny the company is likely to face.

5. Enforcement priorities could shift again.

Agency priorities often change from administration to administration, and the pendulum could swing back again. Companies should assume that shifts in enforcement emphasis are temporary and continue to anchor cyber governance in well-supported risk management practices that can withstand regulatory and judicial scrutiny.

VI. Final Takeaway

The SEC’s decision to dismiss its remaining claims against SolarWinds reflects a narrowing of one enforcement path but still leaves intact significant exposure possibilities, including more traditional securities actions, parallel regulatory regimes, and private litigation. The most durable mitigation is disciplined governance: aligning public statements with verified technical reality, document materiality and incident response judgments, and sustain reasonable, risk based controls. Those steps remain the foundation for withstanding scrutiny from investors, courts, and regulators—regardless of shifting enforcement cycles.

Continue Reading

-

Wealth management firms to pay $25.5 million to settle employees’ class action

WASHINGTON, Nov 21 (Reuters) – A group of major asset and wealth management firms has agreed to pay $25.5 million to resolve claims in U.S. court that they conspired to restrict job mobility and suppress wages for thousands of financial professionals.

Lawyers for the employees on Thursday asked a federal judge in Kansas to grant final approval of the settlement.Sign up here.

The nationwide accord covers more than 4,400 current and former employees who worked for companies including Mariner Wealth Advisors and American Century Companies between 2012 and 2020. The plaintiffs sued last year , alleging the companies violated antitrust law by agreeing not to recruit or hire each other’s workers.American Century and another defendant, Montage Investments, previously reached non-prosecution agreements with the U.S. Justice Department over related allegations, according to the filing.

In a statement, American Century said it was pleased to resolve the workers’ lawsuit in Kansas and “remains committed to fair and honest competition in compliance with all laws and regulations.”

A lawyer for Mariner Wealth and Montage did not immediately respond to a request for comment, and neither did lead attorneys for the plaintiffs.

The asset and wealth management firms denied any wrongdoing.

The plaintiffs said the Mariner defendants have about $65.9 billion in assets under management and the American Century defendants manage about $230 billion in assets.

The plaintiffs said the settlement offers significant and immediate relief and avoids the risk and costs of continuing litigation.

Settlement payments will be based on factors including length of employment, the court papers showed.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs estimated an average payout of about $3,700 per person. Eligible employees will receive payments automatically.

The settlement also said the plaintiffs’ lawyers will ask for up to one-third of the fund for legal fees, or about $8.5 million.

The case is Jakob Tobler et al v. 1248 Holdings LLC, U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas, No. 2:24-cv-02068-EFM-GEB.

For plaintiffs: George Hanson of Stueve Siegel Hanson, and Rowdy Meeks of Rowdy Meeks Legal Group

For Mariner: Jonathan King of DLA Piper

For American Century: John Schmidtlein of Williams & Connolly

Read more:

US naval shipbuilders seek Supreme Court review in engineers’ pay caseUS judge approves pizza chain Papa John’s ‘no poach’ antitrust settlementUS poultry producers sued by growers over hiring and payPharmacy residents accuse US hospitals of wage-fixing in new lawsuitReporting by Mike Scarcella

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

Continue Reading

-

Bloomberg Hot Pursuit: Bentley Unveils New Supersports – Bloomberg.com

- Bloomberg Hot Pursuit: Bentley Unveils New Supersports Bloomberg.com

- How Bentley Turned A Fat Grand Tourer Into A Blue-Blooded Supercar CarBuzz

- Bentley Unveils Lighter, More Focused Continental GT Supersports for 2027 Yahoo! Autos

- Lightweight…

Continue Reading

-

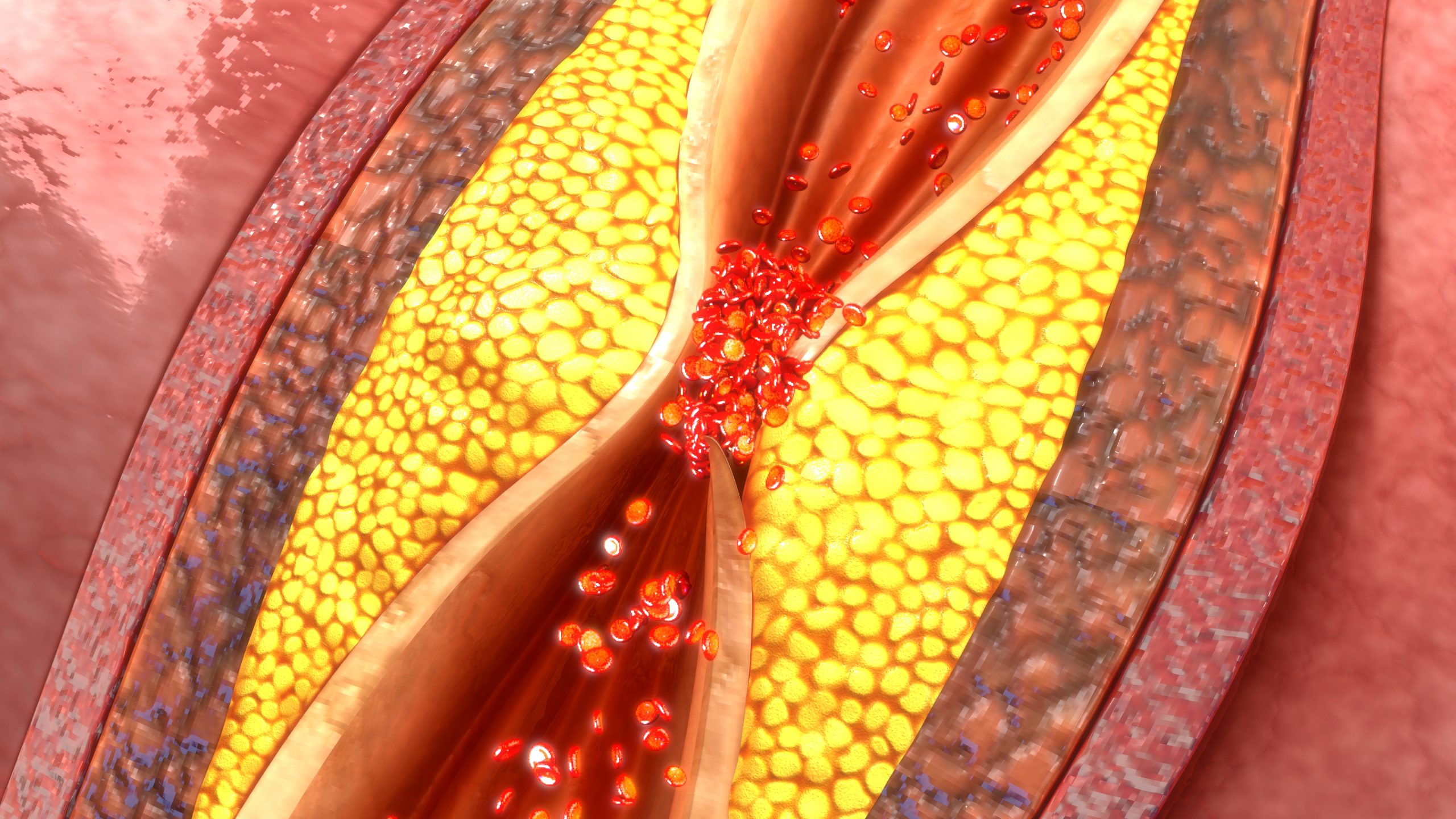

CAR T Cell Therapy for Coronary Artery Disease Shows Early Success

Credit: 7activestudio / Getty Images Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have developed an experimental chimeric antigen receptor regulatory T cell (CAR Treg) to target…

Continue Reading

-

China controls this key resource AI needs – threatening stocks and the U.S. economy

By Kristina Hooper

AI relies on rare-earth elements to grow its infrastructure – and the U.S. relies on AI to grow GDP

Capital spending on AI has been a key driver of U.S. stock market returns and continues to exceed expectations, comprising a large portion of S&P 500 SPX capital expenditures.

Jason Furman, a Harvard University economics professor, calculated that 92% of total U.S. GDP growth for the first half of 2025 could be attributed to AI spending. Without AI-related data-center construction, he reported, GDP growth would have been an anemic 0.1% on an annualized basis.

Given so much riding on the AI capex boom, it’s important to consider what could derail U.S. economic growth and the U.S. stock market

One major risk is access to rare earth elements. Limited rare-earth access could present the U.S. with challenges similar to what it faced in the 1970s from its dependence on oil.

Rare-earth elements are used extensively in artificial intelligence, including disk drives, cooling servers and especially semiconductor fabrication. Artificial intelligence has enormous computational and memory demands, which is why high-capacity, high-performance semiconductors are the linchpin of the AI build-out. Rare earths are also integral for national security – used in radar, lasers and satellite systems.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, the U.S. was the leader in rare-earth elements production. In 1995, two decisions were made that had far-ranging consequences, dramatically changing the trajectory of U.S. leadership in rare earth elements.

First, the U.S. approved China’s purchase of U.S. rare-earth magnet company Magnequench from General Motors, thereby acquiring a highly advanced technology that arguably would have taken many years to develop.

Second, China applied to join the World Trade Organization, ultimately enabling it to sell its rare-earth elements to a global market. China was able to sell at a lower cost than the U.S., contributing to the closure of the U.S. mining company that produced rare earth elements, MP Materials Corp. (MP), in 2002.

MP Materials was reopened for national defense use in 2017. U.S. production has since ramped up, with rare-earth production reaching 45,000 tons in 2024 – yet that’s still less than one-sixth of China’s production.

Yet the U.S. Department of Defense’s lofty goal of meeting defense-related demand for light- and heavy rare earths by 2027 may not be achieved, given America’s rare-earth mining and processing limitations. Even if it is, significant commercial demand, including the enormous AI build-out, will not be met.

China controls the supply

China controls around 70% of the world’s rare earth resource output and about 90% of the world’s rare earth processing capabilities. Access to rare-earth elements has been a key bargaining chip in U.S. trade negotiations with China.

As a result, the U.S. has been increasing efforts to diversify its rare-earths supply and gain reliable and adequate exposure to these elements through its allies. Australia and Canada, for instance, have significant rare-earth resources that can help support America’s rare-earth element needs.

New technologies may also lessen or eliminate the need for rare-earth elements in various uses and make rare-earth element recycling more efficient (currently, just 1% of rare-earth elements are recycled). In addition, U.S. government policies can discourage or at least disincentivize demand for rare earth element-intensive products such as electric vehicles, as the Trump administration has done by eliminating EV tax credits.

Rare earth element independence should be as high a priority for the U.S. as energy independence was 50 years ago. Until there’s a viable alternative to the China-dominated rare-earth supply chain, AI capital spending – and both the U.S. economy and stock market – are vulnerable. Accordingly, stock investors should pay attention to trade deals and policymakers’ comments, and consider supply-chain risks when evaluating AI-related investments.

Kristina Hooper is chief market strategist at Man Group, which manages alternative investments. The opinions expressed are her own.

More: Big Tech is spending on power for AI – whether Washington functions or not

Also read: AI has real problems. The smart money is investing in the companies solving them now.

-Kristina Hooper

This content was created by MarketWatch, which is operated by Dow Jones & Co. MarketWatch is published independently from Dow Jones Newswires and The Wall Street Journal.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

11-21-25 1619ET

Copyright (c) 2025 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

Continue Reading

-

Kristen Bell, Brian Cox Surprised Fox Podcast Uses 2010 Audio

Kristen Bell and Brian Cox were among a string of actors who were recently announced to be voicing Biblical figures in Fox News Audio’s The Life of Jesus Podcast, though they were unaware prior to Wednesday’s announcement of the podcast…

Continue Reading

-

FDA Approves KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) and KEYTRUDA QLEX™ (pembrolizumab and berahyaluronidase alfa-pmph), Each with Padcev® (enfortumab vedotin-ejfv), as Perioperative Treatment for Adults with Cisplatin-Ineligible Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

Represents the first PD-1 inhibitor plus ADC regimens for this patient population

RAHWAY, N.J.–(BUSINESS WIRE)–

Merck (NYSE: MRK), known as MSD outside of the United States and Canada, today announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) and KEYTRUDA QLEX™ (pembrolizumab and berahyaluronidase alfa-pmph) in combination with Padcev® (enfortumab vedotin-ejfv), as neoadjuvant treatment and then continued after cystectomy as adjuvant treatment, for the treatment of adult patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who are ineligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy. These approvals represent the first PD-1 inhibitor plus ADC regimens for this patient population.These approvals are based on data from the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-905 trial (also known as EV-303), which was conducted in collaboration with Pfizer and Astellas. Results, which were presented at the recent European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, showed that after a median follow-up of 25.6 months, KEYTRUDA plus Padcev, as perioperative treatment, demonstrated a statistically significant 60% reduction in the risk of event-free survival (EFS) events versus surgery alone in patients with MIBC who are not eligible for or declined cisplatin-based chemotherapy (HR=0.40 [95% CI, 0.28-0.57]; p<0.0001; 48/170 [28%] versus 95/174 [55%]; median EFS not reached [NR] [95% CI, 37.3-NR] versus 15.7 months [95% CI, 10.3-20.5]). KEYTRUDA plus Padcev also demonstrated a statistically significant 50% improvement in overall survival (OS) versus surgery alone (HR=0.50 [95% CI, 0.33-0.74]; p=0.0002; 38/170 [22%] versus 68/174 [39%]; median OS NR [95% CI, NR-NR] vs 41.7 [95% CI, 31.8-NR]). The trial demonstrated a statistically significant difference in pathologic complete response (pCR) rate (57.1% [95% CI: 49.3, 64.6] vs. 8.6% [95% CI: 4.9, 13.8]; p<0.0001). The effectiveness of KEYTRUDA QLEX for its approved indications has been established based upon evidence from the adequate and well-controlled studies conducted with KEYTRUDA and additional data from MK-3475A-D77 comparing the pharmacokinetic, efficacy, and safety profiles of KEYTRUDA QLEX and KEYTRUDA.

KEYTRUDA QLEX is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to berahyaluronidase alfa, hyaluronidase or to any of its excipients. Immune-mediated adverse reactions, which may be severe or fatal, can occur in any organ system or tissue and can affect more than one body system simultaneously. Immune-mediated adverse reactions can occur at any time during or after treatment with KEYTRUDA or KEYTRUDA QLEX, including pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, nephritis, dermatologic reactions, solid organ transplant rejection, other transplant (including corneal graft) rejection. Additionally, fatal and other serious complications can occur in patients who receive allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) before or after treatment. Consider the benefit vs risks for these patients. Treatment of patients with multiple myeloma with a PD-1/PD-L1-blocking antibody in combination with a thalidomide analogue plus dexamethasone is not recommended outside of controlled trials due to the potential for increased mortality. Important immune-mediated adverse reactions listed here may not include all possible severe and fatal immune-mediated adverse reactions. Early identification and management of immune-mediated adverse reactions are essential to ensure safe use of KEYTRUDA or KEYTRUDA QLEX. Based on the severity of the adverse reaction, KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX should be withheld or permanently discontinued and corticosteroids administered if appropriate. KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can also cause severe or life-threatening infusion-related reactions. Based on their mechanism of action, KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can each cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. For more information, see “Selected Important Safety Information” below.

“Pembrolizumab plus enfortumab vedotin is poised to address a critical unmet need,” said Dr. Matthew Galsky, Lillian and Howard Stratton Professor of Medicine, Director of Genitourinary Medical Oncology, Mount Sinai Tisch Cancer Center, and KEYNOTE-905 study investigator. “Half of patients with MIBC may experience cancer recurrence even after having their bladder removed, and many of these patients are ineligible to receive cisplatin. These approvals, based on striking event-free and overall survival benefits, may represent an important practice-changing advance for these patients who’ve had no new options in decades.”

“Our company’s ongoing commitment to putting patients at the center of finding new innovations in cancer care has made the introduction of these new options a reality for patients who are truly in need,” said Dr. Marjorie Green, senior vice president and head of oncology, global clinical development, Merck Research Laboratories. “Moreover, we are honored to provide these patients who previously had only one option — surgery — with a choice to receive their immunotherapy either intravenously or subcutaneously.”

Study design and additional data supporting the approval

KEYNOTE-905, also known as EV-303, is an open-label, randomized, multi-arm, controlled Phase 3 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03924895) evaluating perioperative KEYTRUDA, with or without Padcev, versus surgery alone in patients with MIBC who are either not eligible for or declined cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The trial enrolled 344 patients who were randomized 1:1 to receive either:

- Neoadjuvant KEYTRUDA 200 mg over 30 minutes as an intravenous infusion on Day 1 and enfortumab vedotin 1.25 mg/kg as an intravenous infusion on Days 1 and 8 of each 21 day cycle for 3 cycles prior to surgery, followed by adjuvant KEYTRUDA 200 mg over 30 minutes on Day 1 of each 21 day cycle for 14 cycles and adjuvant enfortumab vedotin 1.25 mg/kg on Days 1 and 8 of each 21 day cycle for 6 cycles (n=170).

- Immediate radical cystectomy (RC) and pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) alone (n=174).

Treatment continued until completion of study medications, disease progression, not undergoing or refusal of RC and PLND, disease recurrence in the adjuvant phase, or unacceptable toxicity. Assessment of tumor status, including CT/MRI, was performed at baseline, within 5 weeks prior to RC and PLND, and at 6 weeks post radical cystectomy. Following RC and PLND, assessment of tumor status, including cystoscopy and urine cytology for patients who did not undergo surgery, was performed every 12 weeks up to 2 years, and every 24 weeks thereafter.

A total of 149 (88%) patients in the KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin arm and 156 (90%) patients in the RC and PLND alone arm underwent RC and PLND.

The trial was not designed to isolate the effect of KEYTRUDA in each phase (neoadjuvant or adjuvant) of treatment.

The major efficacy outcome measure of this trial was EFS defined as the time from randomization to the first of: disease progression preventing curative surgery, failure to undergo surgery for participants with muscle invasive residual disease, incomplete surgical resection, local or distant recurrence after surgery, or death. OS and pCR rate as assessed by blinded independent pathology review were additional efficacy outcome measures.

For the 167 patients who received KEYTRUDA in the neoadjuvant phase, the median duration of exposure to KEYTRUDA 200 mg every 3 weeks was 1.4 months (range: 1 day to 2.7 months) and the median number of cycles of KEYTRUDA was 3 (range: 1 to 3) out of the planned 3 cycles in the neoadjuvant phase. For the 96 patients who received KEYTRUDA in the adjuvant phase, the median duration of exposure to KEYTRUDA 200 mg every 3 weeks was 8.5 months (range: 1 day to 12.9 months) and the median number of cycles of KEYTRUDA was 12 (range: 1 to 14) out of the planned 14 cycles in the adjuvant phase. Across the combined neoadjuvant and adjuvant phases (n=167), the median number of cycles of KEYTRUDA was 5 (range: 1, 17) out of the planned 17 cycles.

In KEYNOTE-905, the most common adverse reactions (≥20%) occurring in cisplatin-ineligible patients with MIBC treated with KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin (n =167) were rash (54%), pruritus (47%), fatigue (47%), peripheral neuropathy (39%), alopecia (35%), dysgeusia (35%), diarrhea (34%), constipation (28%), decreased appetite (28%), nausea (26%), urinary tract infection (24%), dry eye (21%), and weight loss (20%).

In the neoadjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-905, serious adverse reactions occurred in 27% (n=167) of patients; the most frequent (≥2%) were urinary tract infection (3.6%) and hematuria (2.4%). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 1.2% of patients, including myasthenia gravis and toxic epidermal necrolysis (0.6% each). Additional fatal adverse reactions were reported in 2.7% of patients in the post-surgery phase before adjuvant treatment started, including sepsis and intestinal obstruction (1.4% each). Permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA due to an adverse reaction occurred in 15% of patients; the most frequent (>1%) were rash (2.4%, including generalized exfoliative dermatitis), increased alanine aminotransferase, increased aspartate aminotransferase, diarrhea, dysgeusia, and toxic epidermal necrolysis (1.2% each). Of the 167 patients in the KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin arm who received neoadjuvant treatment, 7 (4.2%) patients did not receive surgery due to adverse reactions. The adverse reactions that led to cancellation of surgery were acute myocardial infarction, bile duct cancer, colon cancer, respiratory distress, urinary tract infection, and two deaths due to myasthenia gravis and toxic epidermal necrolysis (0.6% each).

Of the 146 patients who received neoadjuvant treatment with KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin and underwent radical cystectomy, 6 (4.1%) patients experienced delay of surgery (defined as time from last neoadjuvant treatment to surgery exceeding 8 weeks) due to adverse reactions.

In the adjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-905, serious adverse reactions occurred in 43% (n=100); the most frequent (≥2%) were urinary tract infection (8%); acute kidney injury and pyelonephritis (5% each); urosepsis (4%); and hypokalemia, intestinal obstruction, and sepsis (2% each). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 7% of patients, including urosepsis, intracranial hemorrhage, death, myocardial infarction, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and pseudomonal pneumonia (1% each). Permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA due to an adverse reaction occurred in 28% of patients; the most frequent (>1%) were diarrhea (5%), peripheral neuropathy, acute kidney injury, and pneumonitis (2% each).

About KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) injection, 100 mg

KEYTRUDA is an anti-programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) therapy that works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to help detect and fight tumor cells. KEYTRUDA is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands, PD- L1 and PD-L2, thereby activating T lymphocytes which may affect both tumor cells and healthy cells.

Merck has the industry’s largest immuno-oncology clinical research program. There are currently more than 1,600 trials studying KEYTRUDA across a wide variety of cancers and treatment settings. The KEYTRUDA clinical program seeks to understand the role of KEYTRUDA across cancers and the factors that may predict a patient’s likelihood of benefitting from treatment with KEYTRUDA, including exploring several different biomarkers.

About KEYTRUDA QLEX™ (pembrolizumab and berahyaluronidase alfa-pmph) injection for subcutaneous use

KEYTRUDA QLEX is a fixed-combination drug product of pembrolizumab and berahyaluronidase alfa. Pembrolizumab is a programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) blocking antibody and berahyaluronidase alfa enhances dispersion and permeability to enable subcutaneous administration of pembrolizumab. KEYTRUDA QLEX is administered as a subcutaneous injection into the thigh or abdomen, avoiding the 5 cm area around the navel, over one minute every three weeks (2.4 mL) or over two minutes every six weeks (4.8 mL).

Selected KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) and KEYTRUDA QLEX™ (pembrolizumab and berahyaluronidase alfa-pmph) Indications in the U.S.

Urothelial Cancer

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX are each indicated, in combination with enfortumab vedotin, for the treatment of adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer.

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX, as single agents, are each indicated for the treatment of adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma:

- who are not eligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy, or

- who have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy.

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with enfortumab vedotin, as neoadjuvant treatment and then continued after cystectomy as adjuvant treatment, are each indicated for the treatment of adult patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who are ineligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX, as single agents, are each indicated for the treatment of adult patients with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG)-unresponsive, high-risk, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) with carcinoma in situ (CIS) with or without papillary tumors who are ineligible for or have elected not to undergo cystectomy.

See additional selected KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX indications in the U.S. after the Selected Important Safety Information.

Selected Important Safety Information for KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX

Contraindications

KEYTRUDA QLEX is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to berahyaluronidase alfa, hyaluronidase or to any of its excipients.

Severe and Fatal Immune-Mediated Adverse Reactions

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX are monoclonal antibodies that belong to a class of drugs that bind to either the programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) or the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, thereby removing inhibition of the immune response, potentially breaking peripheral tolerance and inducing immune-mediated adverse reactions. Immune-mediated adverse reactions, which may be severe or fatal, can occur in any organ system or tissue, can affect more than one body system simultaneously, and can occur at any time after starting treatment or after discontinuation of treatment. Important immune-mediated adverse reactions listed here may not include all possible severe and fatal immune-mediated adverse reactions.

Monitor patients closely for symptoms and signs that may be clinical manifestations of underlying immune-mediated adverse reactions. Early identification and management are essential to ensure safe use of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatments. Evaluate liver enzymes, creatinine, and thyroid function at baseline and periodically during treatment. For patients with TNBC treated with KEYTRUDA or KEYTRUDA QLEX in the neoadjuvant setting, monitor blood cortisol at baseline, prior to surgery, and as clinically indicated. In cases of suspected immune-mediated adverse reactions, initiate appropriate workup to exclude alternative etiologies, including infection. Institute medical management promptly, including specialty consultation as appropriate.

Withhold or permanently discontinue KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX depending on severity of the immune-mediated adverse reaction. In general, if KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX require interruption or discontinuation, administer systemic corticosteroid therapy (1 to 2 mg/kg/day prednisone or equivalent) until improvement to Grade 1 or less. Upon improvement to Grade 1 or less, initiate corticosteroid taper and continue to taper over at least 1 month. Consider administration of other systemic immunosuppressants in patients whose adverse reactions are not controlled with corticosteroid therapy.

Immune-Mediated Pneumonitis

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause immune-mediated pneumonitis. The incidence is higher in patients who have received prior thoracic radiation. Immune-mediated pneumonitis occurred in 3.4% (94/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including fatal (0.1%), Grade 4 (0.3%), Grade 3 (0.9%), and Grade 2 (1.3%) reactions. Systemic corticosteroids were required in 67% (63/94) of patients. Pneumonitis led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in 1.3% (36) and withholding in 0.9% (26) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement; of these, 23% had recurrence. Pneumonitis resolved in 59% of the 94 patients. Immune-mediated pneumonitis occurred in 5% (13/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including fatal (0.4%), Grade 3 (2%), and Grade 2 (1.2%) adverse reactions.

Pneumonitis occurred in 7% (41/580) of adult patients with resected NSCLC who received KEYTRUDA as a single agent for adjuvant treatment of NSCLC, including fatal (0.2%), Grade 4 (0.3%), and Grade 3 (1%) adverse reactions. Patients received high-dose corticosteroids for a median duration of 10 days (range: 1 day to 2.3 months). Pneumonitis led to discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in 26 (4.5%) of patients. Of the patients who developed pneumonitis, 54% interrupted KEYTRUDA, 63% discontinued KEYTRUDA, and 71% had resolution.

Immune-Mediated Colitis

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause immune-mediated colitis, which may present with diarrhea. Cytomegalovirus infection/reactivation has been reported in patients with corticosteroid-refractory immune-mediated colitis. In cases of corticosteroid-refractory colitis, consider repeating infectious workup to exclude alternative etiologies.

Immune-mediated colitis occurred in 1.7% (48/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 4 (<0.1%), Grade 3 (1.1%), and Grade 2 (0.4%) reactions. Systemic corticosteroids were required in 69% (33/48); additional immunosuppressant therapy was required in 4.2% of patients. Colitis led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in 0.5% (15) and withholding in 0.5% (13) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement; of these, 23% had recurrence. Colitis resolved in 85% of the 48 patients. Immune-mediated colitis occurred in 1.2% (3/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including Grade 3 (0.8%) and Grade 2 (0.4%) adverse reactions.

Hepatotoxicity and Immune-Mediated Hepatitis

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause immune-mediated hepatitis. Immune-mediated hepatitis occurred in 0.7% (19/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 4 (<0.1%), Grade 3 (0.4%), and Grade 2 (0.1%) reactions. Systemic corticosteroids were required in 68% (13/19) of patients; additional immunosuppressant therapy was required in 11% of patients. Hepatitis led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in 0.2% (6) and withholding in 0.3% (9) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement; of these, none had recurrence. Hepatitis resolved in 79% of the 19 patients. Immune-mediated hepatitis occurred in 0.4% (1/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including Grade 2 (0.4%) adverse reactions.

KEYTRUDA With Axitinib or KEYTRUDA QLEX With Axitinib

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX, when either is used in combination with axitinib, can cause hepatic toxicity. Monitor liver enzymes before initiation of and periodically throughout treatment. Consider monitoring more frequently as compared to when the drugs are administered as single agents. For elevated liver enzymes, interrupt KEYTRUDA and axitinib or KEYTRUDA QLEX and axitinib, and consider administering corticosteroids as needed.

With the combination of KEYTRUDA and axitinib, Grades 3 and 4 increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (20%) and increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (13%) were seen at a higher frequency compared to KEYTRUDA alone. Fifty-nine percent of the patients with increased ALT received systemic corticosteroids. In patients with ALT ≥3 times upper limit of normal (ULN) (Grades 2-4, n=116), ALT resolved to Grades 0-1 in 94%. Among the 92 patients who were rechallenged with either KEYTRUDA (n=3) or axitinib (n=34) administered as a single agent or with both (n=55), recurrence of ALT ≥3 times ULN was observed in 1 patient receiving KEYTRUDA, 16 patients receiving axitinib, and 24 patients receiving both. All patients with a recurrence of ALT ≥3 ULN subsequently recovered from the event.

Immune-Mediated Endocrinopathies

Adrenal Insufficiency

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause primary or secondary adrenal insufficiency. For Grade 2 or higher, initiate symptomatic treatment, including hormone replacement as clinically indicated. Withhold KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX depending on severity. Adrenal insufficiency occurred in 0.8% (22/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 4 (<0.1%), Grade 3 (0.3%), and Grade 2 (0.3%) reactions. Systemic corticosteroids were required in 77% (17/22) of patients; of these, the majority remained on systemic corticosteroids. Adrenal insufficiency led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in <0.1% (1) and withholding in 0.3% (8) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement. Adrenal insufficiency occurred in 2% (5/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including Grade 3 (0.4%) and Grade 2 (0.8%) adverse reactions.

Hypophysitis

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause immune-mediated hypophysitis. Hypophysitis can present with acute symptoms associated with mass effect such as headache, photophobia, or visual field defects. Hypophysitis can cause hypopituitarism. Initiate hormone replacement as indicated. Withhold or permanently discontinue KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX depending on severity. Hypophysitis occurred in 0.6% (17/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA,

including Grade 4 (<0.1%), Grade 3 (0.3%), and Grade 2 (0.2%) reactions. Systemic corticosteroids were required in 94% (16/17) of patients; of these, the majority remained on systemic corticosteroids. Hypophysitis led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in 0.1% (4) and withholding in 0.3% (7) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement.

Thyroid Disorders

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause immune-mediated thyroid disorders. Thyroiditis can present with or without endocrinopathy. Hypothyroidism can follow hyperthyroidism. Initiate hormone replacement for hypothyroidism or institute medical management of hyperthyroidism as clinically indicated. Withhold or permanently discontinue KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX depending on severity.

Thyroiditis occurred in 0.6% (16/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 2 (0.3%). None discontinued, but KEYTRUDA was withheld in <0.1% (1) of patients.

Hyperthyroidism occurred in 3.4% (96/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 3 (0.1%) and Grade 2 (0.8%). It led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in <0.1% (2) and withholding in 0.3% (7) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement. Hypothyroidism occurred in 8% (237/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 3 (0.1%) and Grade 2 (6.2%). It led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in <0.1% (1) and withholding in 0.5% (14) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement. The majority of patients with hypothyroidism required long-term thyroid hormone replacement. The incidence of new or worsening hypothyroidism was higher in 1185 patients with HNSCC, occurring in 16% of patients receiving KEYTRUDA as a single agent or in combination with platinum and FU, including Grade 3 (0.3%) hypothyroidism. The incidence of new or worsening hyperthyroidism was higher in 580 patients with resected NSCLC, occurring in 11% of patients receiving KEYTRUDA as a single agent as adjuvant treatment, including Grade 3 (0.2%) hyperthyroidism. The incidence of new or worsening hypothyroidism was higher in 580 patients with resected NSCLC, occurring in 22% of patients receiving KEYTRUDA as a single agent as adjuvant treatment (KEYNOTE-091), including Grade 3 (0.3%) hypothyroidism.

Thyroiditis occurred in 0.4% (1/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including Grade 2 (0.4%). Hyperthyroidism occurred in 8% (20/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including Grade 2 (3.2%). Hypothyroidism occurred in 14% (35/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including Grade 2 (11%).

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (DM), Which Can Present With Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Monitor patients for hyperglycemia or other signs and symptoms of diabetes. Initiate treatment with insulin as clinically indicated. Withhold KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX depending on severity. Type 1 DM occurred in 0.2% (6/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA. It led to permanent discontinuation in <0.1% (1) and withholding of KEYTRUDA in <0.1% (1) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement. Type 1 DM occurred in 0.4% (1/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy.

Immune-Mediated Nephritis With Renal Dysfunction

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause immune-mediated nephritis.

Immune-mediated nephritis occurred in 0.3% (9/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 4 (<0.1%), Grade 3 (0.1%), and Grade 2 (0.1%) reactions. Systemic corticosteroids were required in 89% (8/9) of patients. Nephritis led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in 0.1% (3) and withholding in 0.1% (3) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement; of these, none had recurrence. Nephritis resolved in 56% of the 9 patients.

Immune-Mediated Dermatologic Adverse Reactions

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause immune-mediated rash or dermatitis. Exfoliative dermatitis, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and toxic epidermal necrolysis, has occurred with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatments. Topical emollients and/or topical corticosteroids may be adequate to treat mild to moderate nonexfoliative rashes. Withhold or permanently discontinue KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX depending on severity.

Immune-mediated dermatologic adverse reactions occurred in 1.4% (38/2799) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA, including Grade 3 (1%) and Grade 2 (0.1%) reactions. Systemic corticosteroids were required in 40% (15/38) of patients. These reactions led to permanent discontinuation in 0.1% (2) and withholding of KEYTRUDA in 0.6% (16) of patients. All patients who were withheld reinitiated KEYTRUDA after symptom improvement; of these, 6% had recurrence. The reactions resolved in 79% of the 38 patients. Immune-mediated dermatologic adverse reactions occurred in 1.6% (4/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with chemotherapy, including Grade 4 (0.8%) and Grade 3 (0.8%) adverse reactions.

Other Immune-Mediated Adverse Reactions

The following clinically significant immune-mediated adverse reactions occurred at an incidence of <1% (unless otherwise noted) in patients who received KEYTRUDA, KEYTRUDA QLEX, or were reported with the use of other anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatments. Severe or fatal cases have been reported for some of these adverse reactions. Cardiac/Vascular: Myocarditis, pericarditis, vasculitis; Nervous System: Meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis and demyelination, myasthenic syndrome/myasthenia gravis (including exacerbation), Guillain-Barré syndrome, nerve paresis, autoimmune neuropathy; Ocular: Uveitis, iritis and other ocular inflammatory toxicities can occur. Some cases can be associated with retinal detachment. Various grades of visual impairment, including blindness, can occur. If uveitis occurs in combination with other immune-mediated adverse reactions, consider a Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like syndrome, as this may require treatment with systemic steroids to reduce the risk of permanent vision loss; Gastrointestinal: Pancreatitis, to include increases in serum amylase and lipase levels, gastritis (2.8%), duodenitis; Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue: Myositis/polymyositis, rhabdomyolysis (and associated sequelae, including renal failure), arthritis (1.5%), polymyalgia rheumatica; Endocrine: Hypoparathyroidism; Hematologic/Immune: Hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi lymphadenitis), sarcoidosis, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, solid organ transplant rejection, other transplant (including corneal graft) rejection.

Hypersensitivity and Infusion- or Administration-Related Reactions

KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can cause severe or life-threatening administration-related reactions, including hypersensitivity and anaphylaxis. With KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX, monitor for signs and symptoms of infusion- and administration-related systemic reactions including rigors, chills, wheezing, pruritus, flushing, rash, hypotension, hypoxemia, and fever. Infusion-related reactions have been reported in 0.2% of 2799 patients receiving KEYTRUDA. Interrupt or slow the rate of infusion for Grade 1 or Grade 2 reactions. For Grade 3 or Grade 4 reactions, stop infusion and permanently discontinue KEYTRUDA. Hypersensitivity and administration related systemic reactions occurred in 3.2% (8/251) of patients receiving KEYTRUDA QLEX in combination with platinum doublet chemotherapy, including Grade 2 (2.8%). Interrupt injection (if not already fully administered) and resume if symptoms resolve for mild or moderate systemic reactions. For severe or life-threatening systemic reactions, stop injection and permanently discontinue KEYTRUDA QLEX.

Complications of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Fatal and other serious complications can occur in patients who receive allogeneic HSCT before or after anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatments. Transplant-related complications include hyperacute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), acute and chronic GVHD, hepatic veno-occlusive disease after reduced intensity conditioning, and steroid-requiring febrile syndrome (without an identified infectious cause). These complications may occur despite intervening therapy between anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatments and allogeneic HSCT. Follow patients closely for evidence of these complications and intervene promptly. Consider the benefit vs risks of using anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatments prior to or after an allogeneic HSCT.

Increased Mortality in Patients With Multiple Myeloma

In trials in patients with multiple myeloma, the addition of KEYTRUDA to a thalidomide analogue plus dexamethasone resulted in increased mortality. Treatment of these patients with an anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatment in this combination is not recommended outside of controlled trials.

Embryofetal Toxicity

Based on their mechanism of action, KEYTRUDA and KEYTRUDA QLEX can each cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Advise women of this potential risk. In females of reproductive potential, verify pregnancy status prior to initiating KEYTRUDA or KEYTRUDA QLEX and advise them to use effective contraception during treatment and for 4 months after the last dose.

Adverse Reactions

In study MK-3475A-D77, when KEYTRUDA QLEX was administered with chemotherapy in metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), serious adverse reactions occurred in 39% of patients. Serious adverse reactions in ≥1% of patients who received KEYTRUDA QLEX were pneumonia (10%), thrombocytopenia (4%), febrile neutropenia (4%), neutropenia (2.8%), musculoskeletal pain (2%), pneumonitis (2%), diarrhea (1.6%), rash (1.2%), respiratory failure (1.2%), and anemia (1.2%). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 10% of patients including pneumonia (3.2%), neutropenic sepsis (2%), death not otherwise specified (1.6%), respiratory failure (1.2%), parotitis (0.4%), pneumonitis (0.4%), pneumothorax (0.4%), pulmonary embolism (0.4%), neutropenic colitis (0.4%), and seizure (0.4%). KEYTRUDA QLEX was permanently discontinued due to an adverse reaction in 16% of 251 patients. Adverse reactions which resulted in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA QLEX in ≥2% of patients included pneumonia and pneumonitis. Dosage interruptions of KEYTRUDA QLEX due to an adverse reaction occurred in 45% of patients. Adverse reactions which required dosage interruption in ≥2% of patients included neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, pneumonia, rash, and increased aspartate aminotransferase. The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were nausea (25%), fatigue (25%), and musculoskeletal pain (21%).

In KEYNOTE-006, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 9% of 555 patients with advanced melanoma; adverse reactions leading to permanent discontinuation in more than one patient were colitis (1.4%), autoimmune hepatitis (0.7%), allergic reaction (0.4%), polyneuropathy (0.4%), and cardiac failure (0.4%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) with KEYTRUDA were fatigue (28%), diarrhea (26%), rash (24%), and nausea (21%).

In KEYNOTE-054, when KEYTRUDA was administered as a single agent to patients with stage III melanoma, KEYTRUDA was permanently discontinued due to adverse reactions in 14% of 509 patients; the most common (≥1%) were pneumonitis (1.4%), colitis (1.2%), and diarrhea (1%). Serious adverse reactions occurred in 25% of patients receiving KEYTRUDA. The most common adverse reaction (≥20%) with KEYTRUDA was diarrhea (28%).

In KEYNOTE-716, when KEYTRUDA was administered as a single agent to patients with stage IIB or IIC melanoma, adverse reactions occurring in patients with stage IIB or IIC melanoma were similar to those occurring in 1011 patients with stage III melanoma from KEYNOTE-054.

In KEYNOTE-189, when KEYTRUDA was administered with pemetrexed and platinum chemotherapy in metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 20% of 405 patients. The most common adverse reactions resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA were pneumonitis (3%) and acute kidney injury (2%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) with KEYTRUDA were nausea (56%), fatigue (56%), constipation (35%), diarrhea (31%), decreased appetite (28%), rash (25%), vomiting (24%), cough (21%), dyspnea (21%), and pyrexia (20%).

In KEYNOTE-407, when KEYTRUDA was administered with carboplatin and either paclitaxel or paclitaxel protein-bound in metastatic squamous NSCLC, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 15% of 101 patients. The most frequent serious adverse reactions reported in at least 2% of patients were febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection. Adverse reactions observed in KEYNOTE-407 were similar to those observed in KEYNOTE-189 with the exception that increased incidences of alopecia (47% vs 36%) and peripheral neuropathy (31% vs 25%) were observed in the KEYTRUDA and chemotherapy arm compared to the placebo and chemotherapy arm in KEYNOTE-407.

In KEYNOTE-042, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 19% of 636 patients with advanced NSCLC; the most common were pneumonitis (3%), death due to unknown cause (1.6%), and pneumonia (1.4%). The most frequent serious adverse reactions reported in at least 2% of patients were pneumonia (7%), pneumonitis (3.9%), pulmonary embolism (2.4%), and pleural effusion (2.2%). The most common adverse reaction (≥20%) was fatigue (25%).

In KEYNOTE-010, KEYTRUDA monotherapy was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 8% of 682 patients with metastatic NSCLC; the most common was pneumonitis (1.8%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were decreased appetite (25%), fatigue (25%), dyspnea (23%), and nausea (20%).

In KEYNOTE-671, adverse reactions occurring in patients with resectable NSCLC receiving KEYTRUDA in combination with platinum-containing chemotherapy, given as neoadjuvant treatment and continued as single-agent adjuvant treatment, were generally similar to those occurring in patients in other clinical trials across tumor types receiving KEYTRUDA in combination with chemotherapy.

The most common adverse reactions (reported in ≥20%) in patients receiving KEYTRUDA in combination with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy were fatigue/asthenia, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, decreased appetite, rash, vomiting, cough, dyspnea, pyrexia, alopecia, peripheral neuropathy, mucosal inflammation, stomatitis, headache, weight loss, abdominal pain, arthralgia, myalgia, insomnia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, urinary tract infection, and hypothyroidism, radiation skin injury, dysphagia, dry mouth, and musculoskeletal pain.

In the neoadjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-671, when KEYTRUDA was administered in combination with platinum-containing chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment, serious adverse reactions occurred in 34% of 396 patients. The most frequent (≥2%) serious adverse reactions were pneumonia (4.8%), venous thromboembolism (3.3%), and anemia (2%). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 1.3% of patients, including death due to unknown cause (0.8%), sepsis (0.3%), and immune-mediated lung disease (0.3%). Permanent discontinuation of any study drug due to an adverse reaction occurred in 18% of patients who received KEYTRUDA in combination with platinum-containing chemotherapy; the most frequent adverse reactions (≥1%) that led to permanent discontinuation of any study drug were acute kidney injury (1.8%), interstitial lung disease (1.8%), anemia (1.5%), neutropenia (1.5%), and pneumonia (1.3%).

Of the KEYTRUDA-treated patients who received neoadjuvant treatment, 6% of 396 patients did not receive surgery due to adverse reactions. The most frequent (≥1%) adverse reaction that led to cancellation of surgery in the KEYTRUDA arm was interstitial lung disease (1%).

In the adjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-671, when KEYTRUDA was administered as a single agent as adjuvant treatment, serious adverse reactions occurred in 14% of 290 patients. The most frequent serious adverse reaction was pneumonia (3.4%). One fatal adverse reaction of pulmonary hemorrhage occurred. Permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA due to an adverse reaction occurred in 12% of patients who received KEYTRUDA as a single agent, given as adjuvant treatment; the most frequent adverse reactions (≥1%) that led to permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA were diarrhea (1.7%), interstitial lung disease (1.4%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (1%), and musculoskeletal pain (1%).

Adverse reactions observed in KEYNOTE-091 were generally similar to those occurring in other patients with NSCLC receiving KEYTRUDA as a single agent, with the exception of hypothyroidism (22%), hyperthyroidism (11%), and pneumonitis (7%). Two fatal adverse reactions of myocarditis occurred.

Adverse reactions observed in KEYNOTE-483 were generally similar to those occurring in other patients receiving KEYTRUDA in combination with pemetrexed and platinum chemotherapy.

In KEYNOTE-689, the most common adverse reactions (≥20%) in patients receiving KEYTRUDA were stomatitis (48%), radiation skin injury (40%), weight loss (36%), fatigue (33%), dysphagia (29%), constipation (27%), hypothyroidism (26%), nausea (24%), rash (22%), dry mouth (22%), diarrhea (22%), and musculoskeletal pain (22%).

In the neoadjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-689, of the 361 patients who received at least one dose of single agent KEYTRUDA, 11% experienced serious adverse reactions. Serious adverse reactions that occurred in more than one patient were pneumonia (1.4%), tumor hemorrhage (0.8%), dysphagia (0.6%), immune-mediated hepatitis (0.6%), cellulitis (0.6%), and dyspnea (0.6%). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 1.1% of patients, including respiratory failure, clostridium infection, septic shock, and myocardial infarction (one patient each). Permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA due to an adverse reaction occurred in 2.8% of patients who received KEYTRUDA as neoadjuvant treatment. The most frequent adverse reaction which resulted in permanent discontinuation of neoadjuvant KEYTRUDA in more than one patient was arthralgia (0.6%).

Of the 361 patients who received KEYTRUDA as neoadjuvant treatment, 11% did not receive surgery. Surgical cancellation on the KEYTRUDA arm was due to disease progression in 4%, patient decision in 3%, adverse reactions in 1.4%, physician’s decision in 1.1%, unresectable tumor in 0.6%, loss of follow-up in 0.3%, and use of non-study anti-cancer therapy in 0.3%.

Of the 323 KEYTRUDA-treated patients who received surgery following the neoadjuvant phase, 1.2% experienced delay of surgery (defined as on-study surgery occurring ≥9 weeks after initiation of neoadjuvant KEYTRUDA) due to adverse reactions, and 2.8% did not receive adjuvant treatment due to adverse reactions.

In the adjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-689, of the 255 patients who received at least one dose of KEYTRUDA, 38% experienced serious adverse reactions. The most frequent serious adverse reactions reported in ≥1% of KEYTRUDA-treated patients were pneumonia (2.7%), pyrexia (2.4%), stomatitis (2.4%), acute kidney injury (2.0%), pneumonitis (1.6%), COVID-19 (1.2%), death not otherwise specified (1.2%), diarrhea (1.2%), dysphagia (1.2%), gastrostomy tube site complication (1.2%), and immune-mediated hepatitis (1.2%). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 5% of patients, including death not otherwise specified (1.2%), acute renal failure (0.4%), hypercalcemia (0.4%), pulmonary hemorrhage (0.4%), dysphagia/malnutrition (0.4%), mesenteric thrombosis (0.4%), sepsis (0.4%), pneumonia (0.4%), COVID-19 (0.4%), respiratory failure (0.4%), cardiovascular disorder (0.4%), and gastrointestinal hemorrhage (0.4%). Permanent discontinuation of adjuvant KEYTRUDA due to an adverse reaction occurred in 17% of patients. The most frequent (≥1%) adverse reactions that led to permanent discontinuation of adjuvant KEYTRUDA were pneumonitis, colitis, immune-mediated hepatitis, and death not otherwise specified.

In KEYNOTE-048, KEYTRUDA monotherapy was discontinued due to adverse events in 12% of 300 patients with HNSCC; the most common adverse reactions leading to permanent discontinuation were sepsis (1.7%) and pneumonia (1.3%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were fatigue (33%), constipation (20%), and rash (20%).

In KEYNOTE-048, when KEYTRUDA was administered in combination with platinum (cisplatin or carboplatin) and FU chemotherapy, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 16% of 276 patients with HNSCC. The most common adverse reactions resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA were pneumonia (2.5%), pneumonitis (1.8%), and septic shock (1.4%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were nausea (51%), fatigue (49%), constipation (37%), vomiting (32%), mucosal inflammation (31%), diarrhea (29%), decreased appetite (29%), stomatitis (26%), and cough (22%).

In KEYNOTE-012, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 17% of 192 patients with HNSCC. Serious adverse reactions occurred in 45% of patients. The most frequent serious adverse reactions reported in at least 2% of patients were pneumonia, dyspnea, confusional state, vomiting, pleural effusion, and respiratory failure. The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were fatigue, decreased appetite, and dyspnea. Adverse reactions occurring in patients with HNSCC were generally similar to those occurring in patients with melanoma or NSCLC who received KEYTRUDA as a monotherapy, with the exception of increased incidences of facial edema and new or worsening hypothyroidism.

In KEYNOTE-A39, when KEYTRUDA was administered in combination with enfortumab vedotin to patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (n=440), fatal adverse reactions occurred in 3.9% of patients, including acute respiratory failure (0.7%), pneumonia (0.5%), and pneumonitis/ILD (0.2%). Serious adverse reactions occurred in 50% of patients receiving KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin; the serious adverse reactions in ≥2% of patients were rash (6%), acute kidney injury (5%), pneumonitis/ILD (4.5%), urinary tract infection (3.6%), diarrhea (3.2%), pneumonia (2.3%), pyrexia (2%), and hyperglycemia (2%). Permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA occurred in 27% of patients. The most common adverse reactions (≥2%) resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA were pneumonitis/ILD (4.8%) and rash (3.4%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) occurring in patients treated with KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin were rash (68%), peripheral neuropathy (67%), fatigue (51%), pruritus (41%), diarrhea (38%), alopecia (35%), weight loss (33%), decreased appetite (33%), nausea (26%), constipation (26%), dry eye (24%), dysgeusia (21%), and urinary tract infection (21%).

In KEYNOTE-052, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 11% of 370 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Serious adverse reactions occurred in 42% of patients; those ≥2% were urinary tract infection, hematuria, acute kidney injury, pneumonia, and urosepsis. The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were fatigue (38%), musculoskeletal pain (24%), decreased appetite (22%), constipation (21%), rash (21%), and diarrhea (20%).

In KEYNOTE-045, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 8% of 266 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. The most common adverse reaction resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA was pneumonitis (1.9%). Serious adverse reactions occurred in 39% of KEYTRUDA-treated patients; those ≥2% were urinary tract infection, pneumonia, anemia, and pneumonitis. The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) in patients who received KEYTRUDA were fatigue (38%), musculoskeletal pain (32%), pruritus (23%), decreased appetite (21%), nausea (21%), and rash (20%).

In KEYNOTE-905, the most common adverse reactions (≥20%) occurring in cisplatin-ineligible patients with MIBC treated with KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin (n =167) were rash (54%), pruritus (47%), fatigue (47%), peripheral neuropathy (39%), alopecia (35%), dysgeusia (35%), diarrhea (34%), constipation (28%), decreased appetite (28%), nausea (26%), urinary tract infection (24%), dry eye (21%), and weight loss (20%).

In the neoadjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-905, serious adverse reactions occurred in 27% (n=167) of patients; the most frequent (≥2%) were urinary tract infection (3.6%) and hematuria (2.4%). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 1.2% of patients, including myasthenia gravis and toxic epidermal necrolysis (0.6% each). Additional fatal adverse reactions were reported in 2.7% of patients in the post-surgery phase before adjuvant treatment started, including sepsis and intestinal obstruction (1.4% each). Permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA due to an adverse reaction occurred in 15% of patients; the most frequent (>1%) were rash (2.4%, including generalized exfoliative dermatitis), increased alanine aminotransferase, increased aspartate aminotransferase, diarrhea, dysgeusia, and toxic epidermal necrolysis (1.2% each). Of the 167 patients in the KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin arm who received neoadjuvant treatment, 7 (4.2%) patients did not receive surgery due to adverse reactions. The adverse reactions that led to cancellation of surgery were acute myocardial infarction, bile duct cancer, colon cancer, respiratory distress, urinary tract infection, and two deaths due to myasthenia gravis and toxic epidermal necrolysis (0.6% each).

Of the 146 patients who received neoadjuvant treatment with KEYTRUDA in combination with enfortumab vedotin and underwent radical cystectomy, 6 (4.1%) patients experienced delay of surgery (defined as time from last neoadjuvant treatment to surgery exceeding 8 weeks) due to adverse reactions.

In the adjuvant phase of KEYNOTE-905, serious adverse reactions occurred in 43% (n=100); the most frequent (≥2%) were urinary tract infection (8%); acute kidney injury and pyelonephritis (5% each); urosepsis (4%); and hypokalemia, intestinal obstruction, and sepsis (2% each). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 7% of patients, including urosepsis, intracranial hemorrhage, death, myocardial infarction, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and pseudomonal pneumonia (1% each). Permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA due to an adverse reaction occurred in 28% of patients; the most frequent (>1%) were diarrhea (5%), peripheral neuropathy, acute kidney injury, and pneumonitis (2% each).

In KEYNOTE-057, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 11% of 148 patients with high-risk NMIBC. The most common adverse reaction resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA was pneumonitis (1.4%). Serious adverse reactions occurred in 28% of patients; those ≥2% were pneumonia (3%), cardiac ischemia (2%), colitis (2%), pulmonary embolism (2%), sepsis (2%), and urinary tract infection (2%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were fatigue (29%), diarrhea (24%), and rash (24%).

Adverse reactions occurring in patients with MSI-H or dMMR CRC were similar to those occurring in patients with melanoma or NSCLC who received KEYTRUDA as a monotherapy.

In KEYNOTE-158 and KEYNOTE-164, adverse reactions occurring in patients with MSI-H or dMMR cancer were similar to those occurring in patients with other solid tumors who received KEYTRUDA as a single agent.

In KEYNOTE-811, fatal adverse reactions occurred in 3 patients who received KEYTRUDA in combination with trastuzumab and CAPOX (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin) or FP (5-FU plus cisplatin) and included pneumonitis in 2 patients and hepatitis in 1 patient. KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 13% of 350 patients with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma. Adverse reactions resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA in ≥1% of patients were pneumonitis (2.0%) and pneumonia (1.1%). In the KEYTRUDA arm vs placebo, there was a difference of ≥5% incidence between patients treated with KEYTRUDA vs standard of care for diarrhea (53% vs 47%), rash (35% vs 28%), hypothyroidism (11% vs 5%), and pneumonia (11% vs 5%).

In KEYNOTE-859, when KEYTRUDA was administered in combination with fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy, serious adverse reactions occurred in 45% of 785 patients. Serious adverse reactions in >2% of patients included pneumonia (4.1%), diarrhea (3.9%), hemorrhage (3.9%), and vomiting (2.4%). Fatal adverse reactions occurred in 8% of patients who received KEYTRUDA, including infection (2.3%) and thromboembolism (1.3%). KEYTRUDA was permanently discontinued due to adverse reactions in 15% of patients. The most common adverse reactions resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA (≥1%) were infections (1.8%) and diarrhea (1.0%). The most common adverse reactions (reported in ≥20%) in patients receiving KEYTRUDA in combination with chemotherapy were peripheral neuropathy (47%), nausea (46%), fatigue (40%), diarrhea (36%), vomiting (34%), decreased appetite (29%), abdominal pain (26%), palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (25%), constipation (22%), and weight loss (20%).

In KEYNOTE-590, when KEYTRUDA was administered with cisplatin and fluorouracil to patients with metastatic or locally advanced esophageal or GEJ (tumors with epicenter 1 to 5 centimeters above the GEJ) carcinoma who were not candidates for surgical resection or definitive chemoradiation, KEYTRUDA was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 15% of 370 patients. The most common adverse reactions resulting in permanent discontinuation of KEYTRUDA (≥1%) were pneumonitis (1.6%), acute kidney injury (1.1%), and pneumonia (1.1%). The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) with KEYTRUDA in combination with chemotherapy were nausea (67%), fatigue (57%), decreased appetite (44%), constipation (40%), diarrhea (36%), vomiting (34%), stomatitis (27%), and weight loss (24%).

Adverse reactions occurring in patients with esophageal cancer who received KEYTRUDA as a monotherapy were similar to those occurring in patients with melanoma or NSCLC who received KEYTRUDA as a monotherapy.

In KEYNOTE-A18, when KEYTRUDA was administered with CRT (cisplatin plus external beam radiation therapy [EBRT] followed by brachytherapy [BT]) to patients with FIGO 2014 Stage III-IVA cervical cancer, fatal adverse reactions occurred in 1.4% of 294 patients, including 1 case each (0.3%) of large intestinal perforation, urosepsis, sepsis, and vaginal hemorrhage. Serious adverse reactions occurred in 34% of patients; those ≥1% included urinary tract infection (3.1%), urosepsis (1.4%), and sepsis (1%). KEYTRUDA was discontinued for adverse reactions in 9% of patients. The most common adverse reaction (≥1%) resulting in permanent discontinuation was diarrhea (1%). For patients treated with KEYTRUDA in combination with CRT, the most common adverse reactions (≥10%) were nausea (56%), diarrhea (51%), urinary tract infection (35%), vomiting (34%), fatigue (28%), hypothyroidism (23%), constipation (20%), weight loss (19%), decreased appetite (18%), pyrexia (14%), abdominal pain and hyperthyroidism (13% each), dysuria and rash (12% each), back and pelvic pain (11% each), and COVID-19 (10%).

In KEYNOTE-826, when KEYTRUDA was administered in combination with paclitaxel and cisplatin or paclitaxel and carboplatin, with or without bevacizumab (n=307), to patients with persistent, recurrent, or first-line metastatic cervical cancer regardless of tumor PD-L1 expression who had not been treated with chemotherapy except when used concurrently as a radio-sensitizing agent, fatal adverse reactions occurred in 4.6% of patients, including 3 cases of hemorrhage, 2 cases each of sepsis and due to unknown causes, and 1 case each of acute myocardial infarction, autoimmune encephalitis, cardiac arrest, cerebrovascular accident, femur fracture with perioperative pulmonary embolus, intestinal perforation, and pelvic infection. Serious adverse reactions occurred in 50% of patients receiving KEYTRUDA in combination with chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab; those ≥3% were febrile neutropenia (6.8%), urinary tract infection (5.2%), anemia (4.6%), and acute kidney injury and sepsis (3.3% each).

KEYTRUDA was discontinued in 15% of patients due to adverse reactions. The most common adverse reaction resulting in permanent discontinuation (≥1%) was colitis (1%).

For patients treated with KEYTRUDA, chemotherapy, and bevacizumab (n=196), the most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were peripheral neuropathy (62%), alopecia (58%), anemia (55%), fatigue/asthenia (53%), nausea and neutropenia (41% each), diarrhea (39%), hypertension and thrombocytopenia (35% each), constipation and arthralgia (31% each), vomiting (30%), urinary tract infection (27%), rash (26%), leukopenia (24%), hypothyroidism (22%), and decreased appetite (21%).

For patients treated with KEYTRUDA in combination with chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab, the most common adverse reactions (≥20%) were peripheral neuropathy (58%), alopecia (56%), fatigue (47%), nausea (40%), diarrhea (36%), constipation (28%), arthralgia (27%), vomiting (26%), hypertension and urinary tract infection (24% each), and rash (22%).