- Police detain protesters heading to Karachi Press Club for TTAP’s protest against 27th Amendment Dawn

- 27th Amendment protest blocked outside Karachi Press Club The Express Tribune

- Sindh Home Minister condemns attack on lawyers in Sukkur, orders…

Author: admin

-

Police detain protesters heading to Karachi Press Club for TTAP’s protest against 27th Amendment – Dawn

-

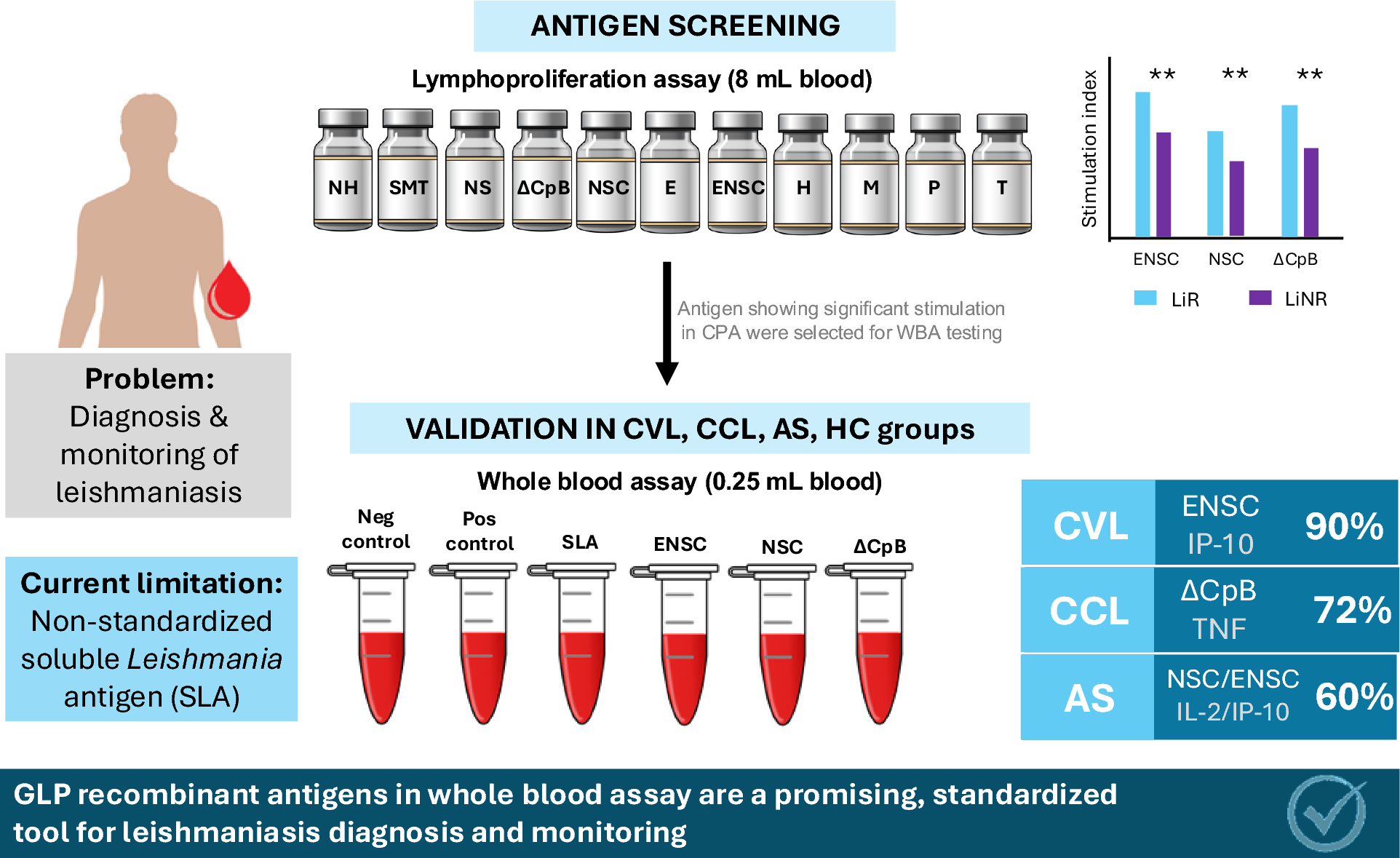

Diagnostic potential of GLP recombinant antigens in whole blood assays for Leishmania infantum infection | Parasites & Vectors

Ruiz-Postigo JA, Grouta L, Jain S. Global leishmaniasis surveillance, 2017–2018, and first report on 5 additional indicators. Wkl Epidemiol Rec WHO. 2020;25:265–80.

Singh OP, Hasker E, Sacks D,…

Continue Reading

-

Jimmy Kimmel accuses Trump of trying to get him fired and tells him: ‘Quiet, piggy’ | US news

Early on Thursday morning, Donald Trump made another plea for ABC to fire the late-night comedian Jimmy Kimmel, writing on his Truth Social platform that he has “NO TALENT” and “VERY POOR TELEVISION RATINGS”.

On his show later that night,…

Continue Reading

-

Statement by the Spokesperson

On several media queries soliciting Pakistan’s comment on the sentence awarded in the trial of the Former Prime Minister of Bangladesh, the Spokesperson stated the following:

This is an internal matter of…

Continue Reading

-

Two thirds of women gain ‘too much or too little’ weight in pregnancy – Nursing Times

- Two thirds of women gain ‘too much or too little’ weight in pregnancy Nursing Times

- Two thirds of women experience too much or too little weight gain in pregnancy BMJ Group

- Why weight during pregnancy has a big impact on both mums and…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists Recreate Conditions from the First Moments After the Big Bang – Hungary Today

- Scientists Recreate Conditions from the First Moments After the Big Bang Hungary Today

- UIC scientists recreate the universe’s first moments by slamming together oxygen ions UIC today

- STAR Pinpoints Quark-Gluon Plasma Phase Transition…

Continue Reading

-

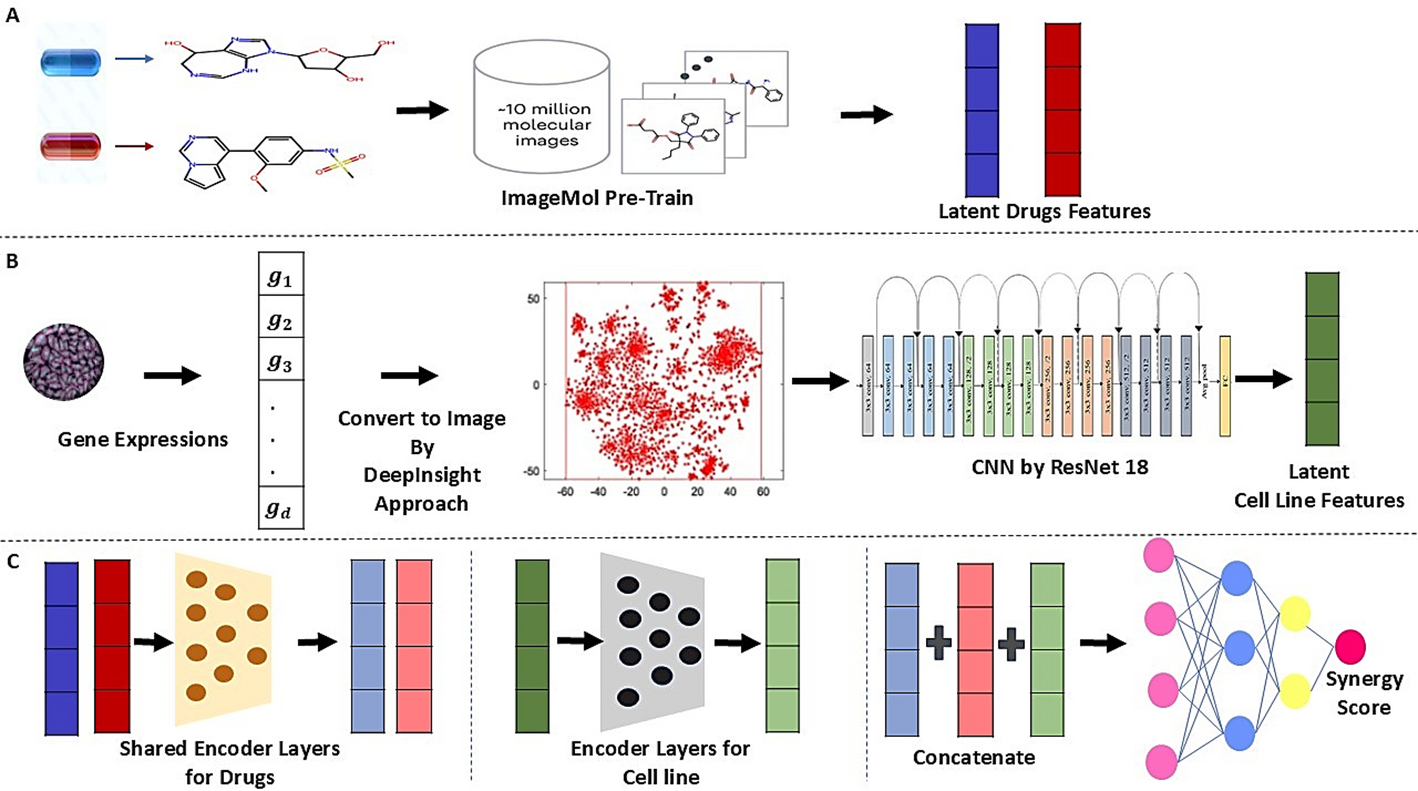

SynergyImage: image-based model for drug combinations synergy score prediction | BMC Bioinformatics

Overview of SynergyImage

The SynergyImage model consists of three steps for predicting drug synergy scores.

-

i.

Image-based features related to each drug are…

Continue Reading

-

i.

-

Best of the Week: Coverage of the EAS Conference, Detecting Lunar Water Ice

This week, Spectroscopy published a variety of articles highlighting recent studies in several application areas. Key techniques highlighted in these articles include nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), visible and near-infrared (VNIR)…

Continue Reading

-

Mahira Khan breaks down in tears in Dubai as Fawad Khan opens up about struggles: ‘It hasn’t been easy’

Dubai: What made Mahira Khan cry in Dubai? Not exhaustion. Not travel chaos. Not the wrong, old passport in hand. Not the whirlwind Neelofar promotions.

She cried because her Humsafar co-star Fawad Khan — normally guarded, composed, and famously…

Continue Reading

-

Spinning into the merging binary black hole family tree – Astrobites

- Spinning into the merging binary black hole family tree Astrobites

- The Most Massive Black Hole Merger Ever Seen Was So Rare, It Seemed Impossible. Now, Astrophysicists May Finally Have an Explanation Smithsonian Magazine

- Twin Black Hole…

Continue Reading