Continue Reading

Several therapeutic advances have reshaped the treatment landscape in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) over the past year, signaling a long-anticipated shift away from historically stagnant standards of care (SOC) and toward a more dynamic, targeted paradigm, according to Charles M. Rudin, MD, PhD, who added that the future of drug development for this disease has never been brighter.1

In a presentation delivered during the

“2025 has been a real banner year for SCLC research, with some promising data emerging,” Rudin, who is a thoracic medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, stated

Rudin also serves as deputy director of the Cancer Center, co-director of the Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research, and the Sylvia Hassenfeld Chair in Lung Cancer Research.

Checkpoint inhibitors have now become embedded in the management of extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC), but their impact is complex, Rudin explained. In limited-stage SCLC, durvalumab (Imfinzi) has recently shifted a decades-long paradigm dominated by concurrent platinum-based chemoradiotherapy alone.

Data from the phase 3 ADRIATIC trial (NCT03703297), which supported

“On the one hand, we do see real, long-term, transformative benefit [with checkpoint inhibitors] in a small subset of patients,” Rudin said about this “yin and yang” of immune checkpoint blockade in SCLC.1 “We have patients with metastatic SCLC who are cured with immunotherapy. That is good for those patients, but it leaves out [approximately] 85% of the patients who [derive] no benefit from the addition of immune checkpoint blockade.”

Ultimately, checkpoint blockade has changed the SOC in SCLC, but only for a minority of patients, underscoring the need for additional strategies to broaden the benefit of immunotherapy, Rubin asserted.

One emerging strategy for bolstering immunotherapy responses in SCLC is to intensify the maintenance phase by layering cytotoxic agents onto PD-L1 inhibition. The phase 3 IMforte trial (NCT05091567) explored the addition of lurbinectedin (Zepzelca) to atezolizumab (Tecentriq) vs atezolizumab alone as maintenance therapy in ES-SCLC after induction therapy.3

Primary results presented at the

“This is a win. It’s a good drug and it works,” Rudin said. “However, I’m not sure this is as practice changing as I would like. One criticism that has been raised about this study is that only a minority of these patients on the control arm ever [received] lurbinectedin.”

Rubin also pointed out the clinical trade-off of introducing a cytotoxic agent at a time when patients might otherwise enjoy a chemotherapy break. In his view, a key goal of maintenance strategies should be to prolong survival outcomes, and he did not see compelling evidence from IMforte that the tail of the Kaplan-Meier curve was substantially altered.

“We need more follow-up from this trial, and we still need to work on better maintenance strategies.”

T-cell engagers represent one of the most promising new modalities in SCLC, particularly because they bypass some of the limitations of antigen presentation that constrain checkpoint blockade, Rubin explained. Tarlatamab (Imdelltra) is currently “the hot drug in this field,” although several other T-cell engagers are demonstrating comparable activity.

Rudin pointed to pivotal data from the phase 3 DeLLphi-304 trial (NCT05740566), which compared tarlatamab with chemotherapy in patients with previously treated ES-SCLC. Data published in the New England Journal of Medicine and presented at the

Importantly, prior exposure to PD-L1 blockade did not appear to negatively affect benefit with tarlatamab. In patients who had received prior anti–PD-L1 agents, the median OS was 14.1 months with tarlatamab vs 8.3 months with chemotherapy (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.45-0.82). In those without prior anti–PD-L1 therapy, median OS was 13.6 vs 8.3 months, respectively (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.42-1.03).

“I would argue that this is, for most patients, the new SOC in this country,” Rudin said, adding that the magnitude and consistency of benefit make tarlatamab compelling in the second line.

Rudin also highlighted emerging data signaling the potential efficacy of tarlatamab as part of frontline maintenance regimens. Extended follow-up from the phase 1b

Additional cohort data from DeLLphi-303 presented at the 2025 ESMO Congress explored tarlatamab in combination with frontline chemoimmunotherapy (n = 96) in ES-SCLC.8 At a median follow-up of 13.8 months (95% CI, 12.5-15.0), the ORR was 71% (95% CI, 61%-80%), with a complete response (CR) rate of 5% and a partial response rate of 66%; 11% of patients had stable disease, 8% had progressive disease, and responses were not evaluable in 9%. The median DOR was 11.0 months (95% CI, 8.5-NE), the DCR was 82% (95% CI, 73%-89%), and the median duration of disease control was 10.7 months (95% CI, 7.7-18.8).

“These are really striking results,” Rudin remarked. “We have not seen these sorts of survival curves for patients with recurrent SCLC. Even in the maintenance setting, you could argue the start of these curves should be lower… but this looks really good. [These are] early data, but this is a 96-patient trial—that is not to be [discounted].”

ADCs are another major component of what Rudin described as a new wave of drug development in SCLC, specifically targeting cell surface proteins rather than driver oncogenes. He focused on 2 agents that he believes may ultimately challenge platinum/etoposide in the frontline setting: the B7-H3–directed ADC ifinatamab deruxtecan (I-DXd) and a seizure-related homolog protein 6 (SEZ6)–targeting ADC ABBV-706.1

In the phase 2 IDeate-Lung01 trial (NCT05280470), patients who received I-DXd at the 12-mg/kg dose (n = 137) achieved a confirmed ORR of 48.2% (95% CI, 39.6%-56.9%), which included a 2.2% CR rate. The DCR was 87.6% (95% CI, 80.9%-92.6%).9

The median PFS was 4.9 months (95% CI, 4.2-5.5), with 3-, 6-, and 9-month PFS rates of 68.0% (95% CI, 59.4%-75.2%), 35.3% (95% CI, 27.3%-43.4%), and 19.3% (95% CI, 12.9%-26.5%), respectively. The median OS was 10.3 months (95% CI, 9.1-13.3), and the 3-, 6-, and 9-month OS rates were 89.1% (95% CI, 82.5%-93.2%), 77.4% (95% CI, 69.4%-83.5%), and 59.1% (95% CI, 50.4%-66.8%), respectively.

In August 2025,

“We have not seen this sort of activity for a cytotoxic in SCLC in a long time,” Rudin commented. “This is delivering the cytotoxic to the tumor, and we are seeing response rates in the second-line setting of over 50%.”

Updated data from the dose-optimization portion of a phase 1 trial (NCT05599984), presented at the IASLC 2025 World Conference on Lung Cancer, showed that ABBV-706 induced a confirmed ORR (cORR) of 58% in the total population (n = 80).11

Responses were observed across key clinical subgroups, including patients with platinum-refractory or -resistant disease and those with brain metastases. Among patients who had received 2 prior lines of therapy (n = 30) or at least 3 prior lines (n = 50), the confirmed ORRs (cORR) were 77% and 46%, respectively. For patients with a CFI of at least 90 days (n = 30), less than 90 days (n = 41), and less than 30 days (n = 19), cORRs were 57%, 59%, and 53%, respectively. Among patients with (n = 28) and without (n = 36) brain metastases at baseline, cORRs were 57% and 69%, respectively. Notably, SEZ6 expression levels were similar between responders and nonresponders.

“These are also nice-looking data, with a large majority of patients benefiting,” Rudin added. “[Both of these ADCs] have [produced] high response rates and have the potential to displace platinum-etoposide as a first-line therapy. We will see if that happens.”

Across checkpoint inhibitors, T-cell engagers, and ADCs, Rudin pointed to a unifying theme: All the most promising agents in SCLC are targeting the cell surface rather than oncogenic drivers.1 “This is a very different strategy than what we have seen for, say, lung adenocarcinoma, where we made such progress by defining driver mutations and specifically subsetting disease and going after these driver mutations one by one,” he explained. “That does not work in SCLC.”

SCLC is characterized by loss of key tumor suppressor genes rather than discrete kinase drivers, making traditional targeted approaches unsuccessful. Accordingly, unconventional targets such as LSD1and EZH2, as well as a range of cell surface proteins, are now under investigation.

“It is a different, orthogonal strategy, but it is one that is increasingly exciting for this disease,” Rudin concluded.

Looking ahead, Rudin envisions a treatment paradigm in which frontline chemoimmunotherapy is followed by more effective maintenance combinations, second-line T-cell engagers become new standards, and ADCs like I-DXd and ABBV-706 potentially move into the first-line setting, transforming what has been one of the most therapeutically constrained areas in lung cancer.

Mutations in a gene associated with Crohn’s disease have been found to rob critical immune cells of their ability to switch modes, causing them to overreact and trigger inflammation.

Variations in the NOD2 gene have been linked to Crohn’s in

JERUSALEM, Nov 16 (Reuters) – Israel’s economy grew an annualised 12.4% in the third quarter, the Central Bureau of Statistics said on Sunday, in data that showed a bounceback from a weak second quarter that was hit more by the Gaza war.

The gain in gross domestic product in the July-September period topped a Reuters consensus of an 8% expansion and was led by broad-based gains led by consumer spending, exports and investment.

Sign up here.

GDP in the second quarter was revised to a 4.3% contraction from a prior 3.9%.

Reporting by Steven Scheer; Editing by Andrew Heavens

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

Mutations in a gene associated with Crohn’s disease have been found to rob critical immune cells of their ability to switch modes, causing them to overreact and trigger inflammation.

Variations in the NOD2 gene have been linked to Crohn’s in

The iPhone 15 Pro was the first iPhone capable of running Apple Intelligence. Apple’s routine is that as the new slew of iPhones are launched that the Pro and Pro Max models of the previous generation are immediately discontinued. Here’s how…

After two decades of breeding what the Times of London once called the “Rolls-Royce of turkey,” Paul Kelly wanted to learn from experts with generations of knowledge in America, where turkey farming originated. But once the Briton arrived in 2003, and after spending several weeks visiting turkey farms across Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, Kelly was “amazed” to find no farmer or butchery maintained the American traditions, including dry-plucking and hanging, that have set the Essex, England-based KellyBronze apart.

Then again, when a frozen American Butterball costs about a $1 a pound and you’re asking customers to pay around $15 a pound—or nearly $500 for a 32-lb. turkey—high quality has to come with more than a high price.

“I thought, it’s almost impertinent for an Englishman to take turkeys to America,” says Kelly. “But there’s an opportunity there. I started looking, and we took it big.”

Kelly, 62, is now the owner of the only USDA-approved turkey plant in the U.S. that dry-plucks and hangs its birds, which many believe creates crispier skin and better flavor. Since purchasing 130 acres in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Crozet, Virginia a decade ago, Kelly has opened America’s first newly built turkey hatchery in years.

KellyBronze, which sells its turkeys at Eataly and other high-end retailers across America, had 2024 revenue of $28 million. About 4% of that comes from the U.S., but Kelly expects that to be 25% within three years as he increases production in Virginia—and he is aiming for annual revenue will hit $80 million by 2028.

Founded in 1971 by Kelly’s parents, Derek and Mollie, KellyBronze is 100% family-owned and has never taken any private investment, though there have been many offers over the years. The business has grown steadily for the past six decades with little debt, and it currently has none. “I have slept at night knowing that every decision we made, we could afford to make, rather than hoping it worked,” says Kelly, who admits that the business is challenging as the bulk of revenue comes in November, December and January. “But, in America, bang, we bought the farm, we built the plant, not having sold one turkey. We were taking risks but risks we could afford.”

Kelly acknowledges the high price of his turkeys can be a “problem” but he is quick to point out that his birds are also three times the age of the typical frozen turkey, and lose 3% of their weight during hanging, and it’s all done by hand, which increases labor costs.

“People aren’t buying it to save money, are they?” asks Kelly. “The sales of amazing wines and the best champagnes go through the roof at Thanksgiving in America, the same as here at Christmas. Not everyone can afford it, but for those that can, it’s there.”

In the U.K, KellyBronze supplies high-end butchers and retailers like Harrods and Selfridges. The Royal Family as well as chef and restaurateur Gordon Ramsay have also supported the brand for years.

The Eaten Path: “We are never going to be Butterball,” Kelly says. “We are a small niche player and we just want to be producing the best possible turkey we can for Thanksgiving.”

KellyBronze

In addition to Kelly’s 130 acres in Virginia, the family owns 90 acres across Scotland and England, where it rents another 140 acres. There are also now 13 British farmers raising turkeys for KellyBronze, including British celebrity chef Jamie Oliver, who started raising a flock five years ago, after spending 25 years as a customer. Oliver calls KellyBronze “the turkey equivalent of Wagyu beef or Pata Negra ham—simply the best of its kind.”

“I became a turkey farmer not out of necessity, but to support an extraordinary artisan family and their craft,” Oliver tells Forbes. “The Kelly family are a shining example of what’s right in British farming. They brought back values and methods that were nearly lost to history.”

Now, after more than 50 years in business, KellyBronze is finally ready to feast on America’s high-end turkey market. “We are never going to be a Butterball. We are never going to be big,” says Kelly. “We are a small niche player and we just want to be producing the best possible turkey we can for Thanksgiving.”

Kelly’s parents bought a small farm the year he was born in 1963. His father worked at a big poultry company and after many years he left so the family could start their own turkey business in 1971 when Kelly was 8 years old. Back then, the British turkey industry was producing what was known as “New York Dressed” birds because, as Kelly explains, “the whole tradition of what we do came from America.”

When Kelly returned to the farm after graduating from an agricultural college attached to Scotland’s Glasgow University in 1983, he pushed his family to take their farming to the next level. In 1984, he changed the family’s breed from a white Wrolstad turkey that originated in Oregon to “the old traditional bronze breed.”

Farm To Table: KellyBronze dry-plucks and hangs its turkeys in the American tradition, which many believe creates crispier skin and better flavor.

KellyBronze

He also started bringing the birds outside where they could roam, dust-bathe, and peck in peace. The Kellys also started dry-plucking and then hanging the birds—at first for 7 days and now for 2 to 3 weeks. It was an expensive approach to a type of poultry that is traditionally quite cheap.

“It was a race to the bottom,” he recalls of British turkey farmers at the time. “We were the laughingstock of the industry.”

That first year, the Kellys had an annual revenue around $300,000 (or about $930,000 today). Despite the slow sales, the family doubled down. In 1987, the Kellys bought a former dairy farm for $90,000 at 10% interest over 10 years. The buildings and 5 acres of grasslands (where Kelly later built a house and now lives) helped the family expand its breeding and allowed them to build a small processing facility. “It was a huge step for us but gave us the space to supply the increased demand that came,” Kelly says. “It proved to be the best investment ever.”

By 1990, “the butchers were phoning us,” and by 1994, sales had skyrocketed to $1.2 million. After adding local farmers to their network throughout the 1990s, in 2001, KellyBronze was appointed by then-Prince Charles’ organic food brand Duchy Originals to farm its Christmas turkeys.

In 2003, revenue reached $3.8 million and Kelly was ready to broaden his understanding of traditional techniques and learn from farms in the United States, where it all began. The first turkeys are said to have been imported to England back in 1526, when a trader named William Strickland brought back six birds he obtained from Native Americans during an early voyage across the Atlantic. Eating turkey at Christmastime became fashionable at King Henry VIII’s court, cementing the turkey’s place as a symbol of festivity. The birds then traveled back across the Atlantic, as the colonists at Jamestown in Virginia had shipments of domesticated turkeys arriving on boats from England.

And while no turkey was ever formally recorded at the Pilgrims’ first Thanksgiving with the Wampanoag in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1621, they were plentiful in the region. Benjamin Franklin once famously called the turkey “a much more respectable bird” than the bald eagle and “a true original Native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours.” He even described turkey as “a bird of courage.”

Born To Be Wild: KellyBronze is now producing 4,600 turkeys in the U.S. this year, and Kelly’s hatchery has the capacity to produce 15,000 “poults” every month.

Levon Biss for Forbes

Kelly says the stock he is raising in Virginia is inspired by “the original traditional turkey that was produced in America hundreds of years ago with the Pilgrims.” In 2014, he brought his turkeys back to the continent they originated on, buying his farm for $750,000, and spending another $2.75 million on infrastructure upgrades—with help from a $1 million bank loan that’s already been paid off.

KellyBronze is now producing 4,600 turkeys in the U.S. this year, and Kelly opened his own hatchery in 2018, which has the capacity to produce 15,000 “poults” every month. It’s currently at 5,500 per year and Kelly wants to open another on the East Coast and one on the West Coast.

Doing business in America isn’t easy. For one, sales are super lumpy—95% of Kelly’s U.S. sales occur at Thanksgiving—and KellyBronze might get hit with tariffs from the Trump Administration’s trade war. Kelly shipped turkey eggs from the U.K. to his U.S. hatchery just before the tariff start date. Next season, if the tariffs continue, the eggs could face charges of a few thousand dollars.

“My dream would be for people to order it in January or February of every year. They put their name on one and we’ll grow it to order,” says Kelly, whose son, Toby, 31, and daughter Ella, 28, are now running parts of KellyBronze. “The potential is huge.”

QUICK FACTS

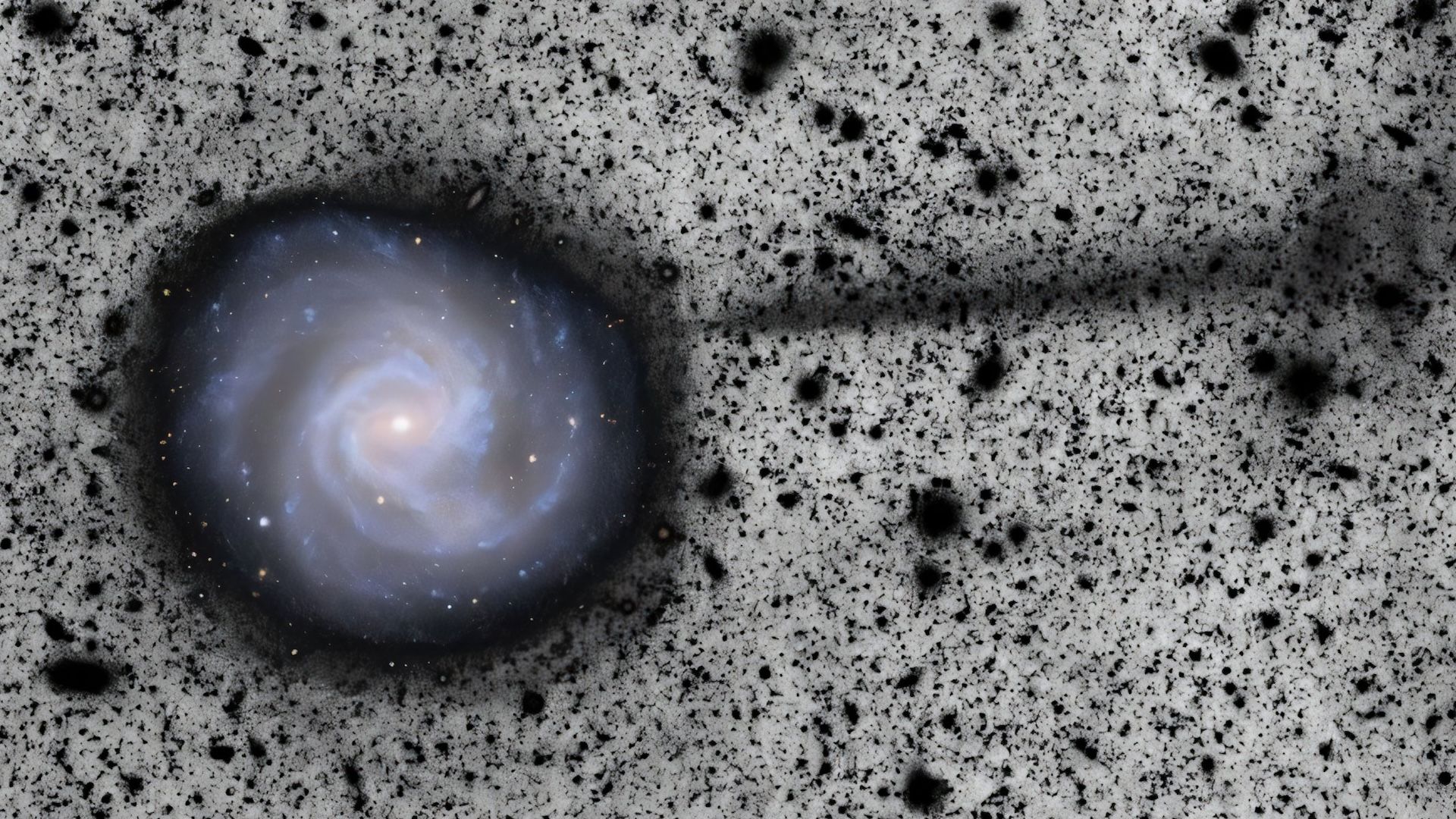

What it is: Barred spiral galaxy Messier 61, AKA NGC 4303

Where it is: 55 million light-years away in the constellation Virgo

When it was shared: Oct. 28, 2025

Even before its full science operations have begun, the Vera C. Rubin…

Watch On

Tune in on Nov. 16 to witness detailed telescopic views of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it races headlong away from the sun on…