Sung JH, et al. An unusual degenerative disorder of neurons associated with a novel intranuclear hyaline inclusion (neuronal intranuclear hyaline inclusion disease). A clinicopathological study of a case. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1980;39(2):107–30.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Sone J, et al. Clinicopathological features of adult-onset neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 12):3170–86.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

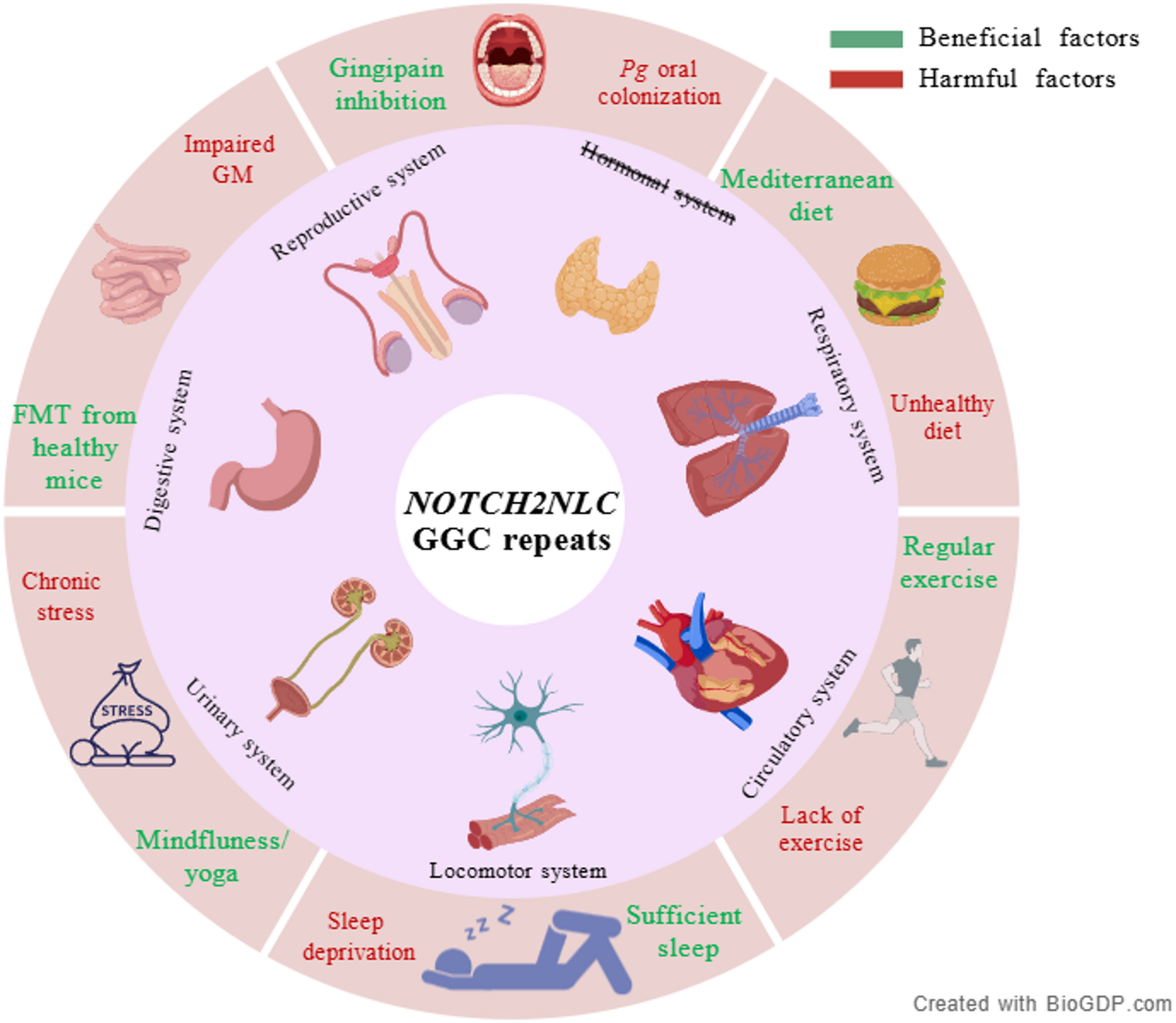

Sone J, et al. Long-read sequencing identifies GGC repeat expansions in NOTCH2NLC associated with neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Nat Genet. 2019;51(8):1215–21.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Tian Y, et al. Expansion of human-specific GGC repeat in neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease-related disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105(1):166–76.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Sun QY, et al. Expansion of GGC repeat in the human-specific NOTCH2NLC gene is associated with essential tremor. Brain. 2020;143(1):222–33.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Ehrlich ME, Ellerby LM. Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease: polyglycine protein is the culprit. Neuron. 2021;109(11):1757–60.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Yu J, et al. CGG repeat expansion in NOTCH2NLC causes mitochondrial dysfunction and progressive neurodegeneration in drosophila model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(41):e2208649119.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Liu Q, et al. Expression of expanded GGC repeats within NOTCH2NLC causes behavioral deficits and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Sci Adv. 2022;8(47):eadd6391.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zhong S, et al. Upstream open reading frame with NOTCH2NLC GGC expansion generates polyglycine aggregates and disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport: implications for polyglycine diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;142(6):1003–23.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Fan Y, et al. GGC repeat expansion in NOTCH2NLC induces dysfunction in ribosome biogenesis and translation. Brain. 2023;146(8):3373–91.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Tian Y, et al. Clinical features of NOTCH2NLC-related neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93(12):1289–98.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Chen H, et al. Re-defining the clinicopathological spectrum of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(10):1930–41.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Tai H, et al. Clinical features and classification of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neurol Genet. 2023;9(2):e200057.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Jiang S, et al. Generic diagramming platform (GDP): a comprehensive database of high-quality biomedical graphics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(D1):D1670–6.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Pang J, et al. The value of NOTCH2NLC gene detection and skin biopsy in the diagnosis of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Front Neurol. 2021;12:624321.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Lee HG, et al. Neuroinflammation: an astrocyte perspective. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15(721):eadi7828.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Bao L et al. Immune system involvement in neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 2024;50(2):e12976.

Mori K, et al. Imaging findings and pathological correlations of subacute encephalopathy with neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease-case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17(12):4481–6.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Prinz M, Priller J. The role of peripheral immune cells in the CNS in steady state and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(2):136–44.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Yoshii D, et al. An autopsy case of adult-onset neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease with perivascular preservation in cerebral white matter. Neuropathology. 2021;42(1):66–73.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Tracey KJ, Cerami A. Tumor necrosis factor: a pleiotropic cytokine and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Med. 1994;45:491–503.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood. 2011;117(14):3720–32.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(10):a016295.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Lu X, Hong D. Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease: recognition and update. J Neural Transm. 2021;128(3):295–303.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Bao L, et al. Utility of labial salivary gland biopsy in the histological diagnosis of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Eur J Neurol. 2024;31(1):e16102.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Zhong S, et al. Spatial and Temporal distribution of white matter lesions in NOTCH2NLC-Related neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neurology. 2025;104(4):e213360.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Du N et al. Value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Heliyon, 2024;10(6):e27953.

Yan Y, et al. The clinical characteristics of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease and its relation with inflammation. Neurol Sci. 2023;44(9):3189–97.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Shen Y et al. uN2CpolyG-mediated p65 nuclear sequestration suppresses the NF-κB-NLRP3 pathway in neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Cell Communication Signal, 2025;23(1):68.

Tateishi J, et al. Intranuclear inclusions in muscle, nervous tissue, and adrenal gland. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;63(1):24–32.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Platero JL et al. The impact of coconut oil and Epigallocatechin gallate on the levels of IL-6, anxiety and disability in multiple sclerosis patients. Nutrients, 2020;12(2):305.

Casali BT, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids augment the actions of nuclear receptor agonists in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2015;35(24):9173–81.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Chauhan A, et al. Phytochemicals targeting NF-κB signaling: potential anti-cancer interventions. J Pharm Anal. 2022;12(3):394–405.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Shabab T, et al. Neuroinflammation pathways: a general review. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127(7):624–33.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1(6):a001651.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Gleeson M, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(9):607–15.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Pedersen BK. Adolph distinguished lecture: muscle as an endocrine organ: IL-6 and other myokines. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;107(4):1006–14. Edward F.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Steensberg A, et al. IL-6 enhances plasma IL-1ra, IL-10, and cortisol in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285(2):E433–7.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Ma Q. Beneficial effects of moderate voluntary physical exercise and its biological mechanisms on brain health. Neurosci Bull. 2008;24(4):265–70.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Adlard PA, et al. Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25(17):4217–21.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Periasamy S, et al. Sleep deprivation-induced multi-organ injury: role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Excli J. 2015;14:672–83.

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Shearer WT, et al. Soluble TNF-alpha receptor 1 and IL-6 plasma levels in humans subjected to the sleep deprivation model of spaceflight. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(1):165–70.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Ooms S, et al. Effect of 1 night of total sleep deprivation on cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 in healthy middle-aged men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):971–7.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Reiter RJ, et al. Brain washing and neural health: role of age, sleep, and the cerebrospinal fluid melatonin rhythm. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(4):88.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zhao HY, et al. Chronic sleep restriction induces cognitive deficits and cortical Beta-Amyloid deposition in mice via BACE1-Antisense activation. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(3):233–40.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, et al. Quercetin ameliorates memory impairment by inhibiting abnormal microglial activation in a mouse model of Paradoxical sleep deprivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;632:10–6.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Irwin MR, et al. Tai Chi compared with cognitive behavioral therapy and the reversal of systemic, cellular and genomic markers of inflammation in breast cancer survivors with insomnia: A randomized clinical trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;120:159–66.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Dutcher JM, et al. Smartphone mindfulness meditation training reduces Pro-inflammatory gene expression in stressed adults: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;103:171–7.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Walsh E, Eisenlohr-Moul T, Baer R. Brief mindfulness training reduces salivary IL-6 and TNF-α in young women with depressive symptomatology. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(10):887–97.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Patel DI, et al. Therapeutic yoga reduces pro-tumorigenic cytokines in cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2022;31(1):33.

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Streeter CC, et al. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78(5):571–9.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Ozturk FO, Tezel A. Effect of laughter yoga on mental symptoms and salivary cortisol levels in first-year nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Pract. 2021;27(2):e12924.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Nair RG, Vasudev MM, Mavathur R. Role of yoga and its plausible mechanism in the mitigation of DNA damage in Type-2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Behav Med. 2022;56(3):235–44.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Chen SJ, et al. Association of fecal and plasma levels of Short-Chain fatty acids with gut microbiota and clinical severity in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2022;98(8):e848–58.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Chakraborty P, Gamage H, Laird AS. Butyrate as a potential therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative disorders. Neurochem Int. 2024;176:105745.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Li N, et al. Prebiotic inulin controls Th17 cells mediated central nervous system autoimmunity through modulating the gut microbiota and short chain fatty acids. Gut Microbes. 2024;16(1):2402547.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, et al. Transmission of alzheimer’s disease-associated microbiota dysbiosis and its impact on cognitive function: evidence from mice and patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(10):4421–37.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Kim MS, et al. Transfer of a healthy microbiota reduces amyloid and Tau pathology in an alzheimer’s disease animal model. Gut. 2020;69(2):283–94.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Beydoun MA, et al. Clinical and bacterial markers of periodontitis and their association with incident All-Cause and alzheimer’s disease dementia in a large National survey. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(1):157–72.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Ilievski V, et al. Chronic oral application of a periodontal pathogen results in brain inflammation, neurodegeneration and amyloid beta production in wild type mice. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0204941.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Wang RP, et al. IL-1β and TNF-α play an important role in modulating the risk of periodontitis and alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2023;20(1):71.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Dominy SS, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in alzheimer’s disease brains: evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5(1):eaau3333.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Brettschneider J, et al. Microglial activation correlates with disease progression and upper motor neuron clinical symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39216.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Graves MC, et al. Inflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord and brain is mediated by activated macrophages, mast cells and T cells. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2004;5(4):213–9.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Henkel JS, et al. Presence of dendritic cells, MCP-1, and activated microglia/macrophages in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord tissue. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(2):221–35.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Liu YH, et al. Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease in patients with adult-onset non-vascular leukoencephalopathy. Brain. 2022;145(9):3010–21.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Chen L, et al. Teaching neuroimages: the zigzag edging sign of adult-onset neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neurology. 2019;92(19):e2295-6.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Fragoso DC, et al. Imaging of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: imaging patterns and their differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2017;37(1):234–57.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Muttikkal TJ, Wintermark M. MRI patterns of global hypoxic-ischemic injury in adults. J Neuroradiol. 2013;40(3):164–71.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Hasebe M, et al. Hypoglycemic encephalopathy. QJM. 2022;115(7):478–9.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Zhang Z, et al. MRI features of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease, combining visual and quantitative imaging investigations. J Neuroradiol. 2024;51(3):274–80.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Okamura S, et al. A case of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease with recurrent vomiting and without apparent DWI abnormality for the first seven years. Heliyon. 2020;6(8):e04675.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Liu Y, et al. Clinical and mechanism advances of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:934725.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Liang H, et al. Clinical and pathological features in adult-onset NIID patients with cortical enhancement. J Neurol. 2020;267(11):3187–98.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Shen Y, et al. Encephalitis-like episodes with cortical edema and enhancement in patients with neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neurol Sci. 2024;45(9):4501–11.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Jacobs AH, Tavitian B. Noninvasive molecular imaging of neuroinflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(7):1393–415.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Corica F et al. PET imaging of Neuro-Inflammation with tracers targeting the translocator protein (TSPO), a systematic review: from bench to bedside. Diagnostics (Basel), 2023;13(6):1029.

Banati RB. Visualising microglial activation in vivo. Glia. 2002;40(2):206–17.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Turner MR, et al. Evidence of widespread cerebral microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an [11 C](R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15(3):601–9.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Tondo G, et al. (11) C-PK11195 PET-based molecular study of microglia activation in SOD1 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(9):1513–23.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Malpetti M, et al. Microglial activation in the frontal cortex predicts cognitive decline in frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2023;146(8):3221–31.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zhong S, et al. Microglia contribute to polyG-dependent neurodegeneration in neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024;148(1):21.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Hutton BF. The origins of SPECT and SPECT/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(Suppl 1):S3-16.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Benadiba M, et al. New molecular targets for PET and SPECT imaging in neurodegenerative diseases. Braz J Psychiatry. 2012;34(Suppl 2):S125–36.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Kimachi T, et al. Reversible encephalopathy with focal brain edema in patients with neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience. 2017;5(6):198–200.

Article

Google Scholar

Fujita K, et al. Neurologic attack and dynamic perfusion abnormality in neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7(6):e39-42.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Pan Y, et al. Expression of expanded GGC repeats within NOTCH2NLC causes cardiac dysfunction in mouse models. Cell Biosci. 2023;13(1):157.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Heslegrave A, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 concentration in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:3.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Craig-Schapiro R, et al. YKL-40: a novel prognostic fluid biomarker for preclinical alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(10):903–12.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Crols R, et al. Increased GFAP levels in CSF as a marker of organicity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other types of irreversible chronic organic brain syndrome. J Neurol. 1986;233(3):157–60.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Andrés-Benito P, et al. Differential astrocyte and oligodendrocyte vulnerability in murine Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Prion. 2021;15(1):112–20.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Mussbacher M, et al. NF-κB in monocytes and macrophages – an inflammatory master regulator in multitalented immune cells. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1134661.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Biasizzo M, Kopitar-Jerala N. Interplay between NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:591803.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Deng Q, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa triggers macrophage autophagy to escape intracellular killing by activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Infect Immun. 2016;84(1):56–66.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Geissmann F, et al. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327(5966):656–61.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Guilliams M, et al. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: a unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(8):571–8.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Prinz M, Jung S, Priller J. Microglia Biology: One Century Evol Concepts Cell. 2019;179(2):292–311.

CAS

Google Scholar

Li Q, Barres BA. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(4):225–42.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Liddelow SA, et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature. 2017;541(7638):481–7.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Keren-Shaul H, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2017;169(7):1276–e129017.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Mathys H, et al. Temporal tracking of microglia activation in neurodegeneration at single-cell resolution. Cell Rep. 2017;21(2):366–80.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zhou Y, et al. Human and mouse single-nucleus transcriptomics reveal TREM2-dependent and TREM2-independent cellular responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2020;26(1):131–42.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44(3):439–49.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Italiani P, Boraschi D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:514.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Merad M, et al. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:563–604.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Sun R, Jiang H. Border-associated macrophages in the central nervous system. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21(1):67.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Goldmann T, et al. Origin, fate and dynamics of macrophages at central nervous system interfaces. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(7):797–805.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Van Hove H, et al. A single-cell atlas of mouse brain macrophages reveals unique transcriptional identities shaped by ontogeny and tissue environment. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(6):1021–35.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular mechanisms and blood-brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(1):103–13.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Faraco G, et al. Perivascular macrophages mediate the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(12):4674–89.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Rua R, et al. Infection drives meningeal engraftment by inflammatory monocytes that impairs CNS immunity. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(4):407–19.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Dani N, et al. A cellular and Spatial map of the choroid plexus across brain ventricles and ages. Cell. 2021;184(11):3056–e307421.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Mrdjen D, et al. High-Dimensional Single-Cell mapping of central nervous system immune cells reveals distinct myeloid subsets in Health, Aging, and disease. Immunity. 2018;48(2):380–95. .e6.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Park L, et al. Brain perivascular macrophages initiate the neurovascular dysfunction of Alzheimer Aβ peptides. Circ Res. 2017;121(3):258–69.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Schläger C, et al. Effector T-cell trafficking between the leptomeninges and the cerebrospinal fluid. Nature. 2016;530(7590):349–53.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Herz J, et al. Role of neutrophils in exacerbation of brain injury after focal cerebral ischemia in hyperlipidemic mice. Stroke. 2015;46(10):2916–25.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):653–60.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Greenberg SM, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):165–74.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Charidimou A, Gang Q, Werring DJ. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy revisited: recent insights into pathophysiology and clinical spectrum. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(2):124–37.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Liao YC, et al. NOTCH2NLC GGC repeat expansion in patients with vascular leukoencephalopathy. Stroke. 2023;54(5):1236–45.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Bao L, et al. GGC repeat expansions in NOTCH2NLC cause uN2CpolyG cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain. 2025;148(2):467–79.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Ryu JK, McLarnon JG. A leaky blood-brain barrier, fibrinogen infiltration and microglial reactivity in inflamed Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(9a):2911–25.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Shan Y, et al. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist reduces inflammation and blood-brain barrier breakdown in an astrocyte-dependent manner in experimental stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):242.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Orihara A, et al. Acute reversible encephalopathy with neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease diagnosed by a brain biopsy: inferring the mechanism of encephalopathy from radiological and histological findings. Intern Med. 2023;62(12):1821–5.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Li YY, et al. Interactions between beta-Amyloid and pericytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2024;29(4):136.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Huang X, Hussain B, Chang J. Peripheral inflammation and blood-brain barrier disruption: effects and mechanisms. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(1):36–47.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Rahimifard M, et al. Targeting the TLR4 signaling pathway by polyphenols: a novel therapeutic strategy for neuroinflammation. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;36:11–9.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Zhang M, et al. Blockage of VEGF function by bevacizumab alleviates early-stage cerebrovascular dysfunction and improves cognitive function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2024;13(1):1.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Wild CP. Complementing the genome with an exposome: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(8):1847–50.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Doroszkiewicz J et al. Common and trace metals in alzheimer’s and parkinson’s diseases. Int J Mol Sci, 2023;24(21):15721.

Gu Y, et al. Mediterranean diet, inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):483–92.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Flanagan E, et al. Nutrition and the ageing brain: moving towards clinical applications. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;62:101079.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Gelpi E, et al. Neuronal intranuclear (hyaline) inclusion disease and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: a morphological and molecular dilemma. Brain. 2017;140(8):e51.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Tolar M et al. Neurotoxic soluble amyloid oligomers drive alzheimer’s pathogenesis and represent a clinically validated target for slowing disease progression. Int J Mol Sci, 2021;22(12):6355.

Habashi M, et al. Early diagnosis and treatment of alzheimer’s disease by targeting toxic soluble Aβ oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(49):e2210766119.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Wang ZX, et al. The essential role of soluble Aβ oligomers in alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(3):1905–24.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haack M. The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(3):1325–80.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Su WJ, et al. Antidiabetic drug glyburide modulates depressive-like behavior comorbid with insulin resistance. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1):210.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(10):717–25.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zhang J, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide induces cognitive dysfunction, mediated by neuronal inflammation via activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway in C57BL/6 mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):37.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Nie R, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection induces Amyloid-β accumulation in Monocytes/Macrophages. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;72(2):479–94.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Kemaladewi DU, et al. Correction of a splicing defect in a mouse model of congenital muscular dystrophy type 1A using a homology-directed-repair-independent mechanism. Nat Med. 2017;23(8):984–9.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Sarkar S, et al. Rapamycin and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers ameliorate toxicity of polyglutamine-expanded Huntingtin and related proteinopathies. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16(1):46–56.

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Grima JC, et al. Mutant Huntingtin disrupts the nuclear pore complex. Neuron. 2017;94(1):93–e1076.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar