Stamm HB. Professional quality of life: compassion satisfaction and fatigue. Pocadello. 2010. https://proqol.org/.

Sacco TL, Copel LC. Compassion satisfaction: a concept analysis in nursing. Nurs Forum. 2018;53(1):76–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12213.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Youn H, Lee M, Jang SJ. Person-centred care among intensive care unit nurses: a cross-sectional study. Intensive And Crit Care Nurs. 2022;73:103293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2022.103293.

Article

Google Scholar

Zhang Y-Y, Han W-L, Qin W, Yin H-X, Zhang C-F, Kong C, Wang Y-L. Extent of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing: a meta-analysis. J Nurs Manag. 2018;26(7):810–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12589.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Toward a new understanding of the costs of caring. In secondary traumatic stress: self-care issues for clinicians, researchers, & educators. Vol. 2nd. Sidran Press; 1995. p. 3–28.

Google Scholar

Joinson C. Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing. 1992;22(4):116, 118–119, 120.

PubMed

Google Scholar

Peters E. Compassion fatigue in nursing: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2018;53(4):466–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12274.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Sinclair S, Raffin-Bouchal S, Venturato L, Mijovic-Kondejewski J, Smith-MacDonald L. Compassion fatigue: a meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:9–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Sorenson C, Bolick B, Wright K, Hamilton R. An evolutionary concept analysis of compassion fatigue. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2017;49(5):557–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12312.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Garnett A, Hui L, Oleynikov C, Boamah S. Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):1336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10356-3.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Sorenson C, Bolick B, Wright K, Hamilton R. Understanding compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: a review of current literature. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(5):456–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12229.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organizational Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113.

Article

Google Scholar

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. 2001;52:397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

Article

Google Scholar

Bianchi R, Truchot D, Laurent E, Brisson R, Schonfeld I. Is burnout solely job-related? A critical comment. Scand J Psychol. 2014;55:357–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12119.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Peeters MCW, Breevaart K. New directions in burnout research. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2021;30(5):686–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1979962.

Article

Google Scholar

Edu-Valsania S, Laguia A, Moriano J. Burnout: a review of theory and measurement. Int J Environ Res Pub Health And Public Health. 2022, (1780;19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031780.

Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Pscychiatry. 2016;15:103–11. https://doi.org.ezproxy.brunel.ac.uk/10.1002/wps.20311

Cavanagh N, Cockett G, Heinrich C, Doig L, Fiest K, Guichon JR, Page S, Mitchell I, Doig CJ. Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(3):639–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019889400.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Maillet S, Read E. Work environment characteristics and emotional intelligence as correlates of nurses’ compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue: a cross-sectional survey study. Nurs Rep. 2021;11(4):847–58. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11040079.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Xie W, Chen L, Feng F, Okoli CTC, Tang P, Zeng L, Jin M, Zhang Y, Wang J. The prevalence of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;120:103973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103973.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Leo CG, Sabina S, Tumolo MR, Bodini A, Ponzini G, Sabato E, Mincarone P. Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID 19 era: a review of the existing literature. Front Public Health. 2021;9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.750529.

Zhang X, Song Y, Jiang T, Ding N, Shi T. Interventions to reduce burnout of physicians and nurses: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med (baltim). 2020;99(26). https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/fulltext/2020/06260/interventions_to_reduce_burnout_of_physicians_and.89.aspx.

De Simone S, Vargas M, Sevillo G. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(4):883–94. https://doi.org.ezproxy.brunel.ac.uk/10.1007/s40520-019-01368-3 .

DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, Boulanger TS, Snowdon JL, Tutty MA, Sinsky CA, Craig KJT. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on Physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clinic Proc: Innovations, Qual & Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.07.006.

Article

Google Scholar

Fox S, Lydon S, Byrne D, Madden C, Connolly F, O’Connor P. A systematic review of interventions to foster physician resilience. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94(1109):162–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135212.

Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, Lewith G, Kontopantelis E, Chew-Graham C, Dawson S, van Marwijk H, Geraghty K, Esmail A. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195–205. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Petrie K, Crawford J, Baker STE, Dean K, Robinson J, Veness BG, Randall J, McGorry P, Christensen H, Harvey SB. Interventions to reduce symptoms of common mental disorders and suicidal ideation in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(3):225–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30509-1.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Coles E, Anderson J, Maxwell M, Harris FM, Gray NM, Milner G, MacGillivray S. The influence of contextual factors on healthcare quality improvement initiatives: a realist review. Systematic Rev. 2020;9(1):94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01344-3.

Article

Google Scholar

Chen C-C, Lan Y-L, Chiou S, Y-C. The effect of emotional labor on the physical and mental health of health professionals: emotional exhaustion has a mediating effect. Healthcare. 2023;11(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010104.

Maben J, Bridges J. Covid-19: Supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J Clin nursing. 2020;29(15–16):2742–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15307.

Article

Google Scholar

Agler R, De Boeck P. On the interpretation and use of mediation: multiple perspectives on mediation analysis. Front psychol. 2017;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01984.

Rohlf VI, Scotney R, Monaghan H, Bennett P. Predictors of professional quality of life in veterinary professionals. J Vet Med Educ. 2022;49(3):372–81. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme-2020-0144.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Rohrer JM, Hünermund P, Arslan RC, Elson M. That’s a lot to process! Pitfalls of popular path models. Adv Met pract psychol Sci. 2022;5(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459221095827.

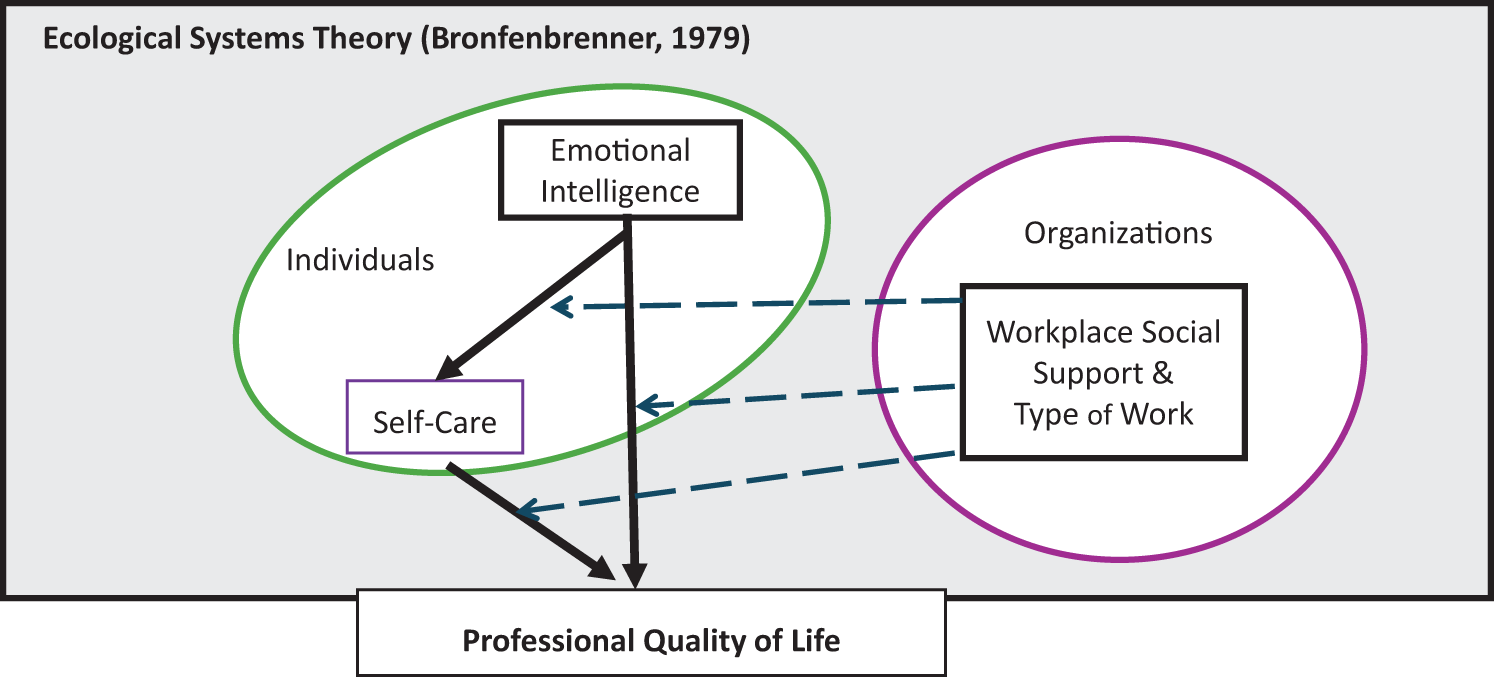

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press; 1979.

Book

Google Scholar

Mayer JD, Salovey P. The intelligence of emotional intelligence. Intelligence. 1993;17:433–42.

Article

Google Scholar

Sarrionandia A, Mikolajzak. A meta-analysis of the possible behavioural and biological variables linking trait emotional intelligence to health. Health Psychol Rev. 2020;14(2):220–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1641423.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Lea R, Davis SK, Mahoney B, Qualter P. Do emotionally intelligent adolescents flourish or flounder under pressure? Linking emotional intelligence to stress regulation mechanisms. Pers Indiv Differ. 2023;201:111943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111943.

Article

Google Scholar

Ma J, Zeng Z, Fang K. Emotionally savvy employees fail to enact emotional intelligence when ostracized. Pers Indiv Differ. 2022;185:111250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111250.

Article

Google Scholar

Pena-Sarrionandia A, Mikolajczak M, Gross JJ. Integrating emotion regulation and emotional intelligence traditions: a meta-analysis. Front psychol. 2015;6:article 160.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Matarese M, Lommi M, Marinis MGD, Riegel B. A systematic review and integration of concept analyses of self-care and related concepts. J Nurs scholarsh. 2018;50(3):296–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12385.

Riegel B, Dunbar SB, Fitzsimons D, Freedland KE, Lee CS, Middleton S, Stromber A, Vellone E, Webber DE, Jaarsma T. Self-care research: Where are we now? Where are we going? Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;116. https://doi-org.ezproxy.brunel.ac.uk/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103402.

Keesler JM, Troxel J. They care for others, but what about themselves? Understanding self-care among DSPs’ and its relationship to professional quality of life. Intellect Dev Disab. 2020;58(3):221–40. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-58.3.221.

Article

Google Scholar

Nogueiro J, Cañas-Lerma AJ, Cuartero-Castañer ME, Bolaños I. The professional quality of life and its relation to self-care in mediation professionals. Soc Work Soc Sci Rev. 2022;23:55–73. https://doi.org/10.1921/swssr.v23i1.1972.

Article

Google Scholar

Bermejo-Martins E, Luis EO, Fernandez-Berrocal P, Martinez M, Sarrionandia A. The role of emotional intelligence and self-care in the stress perception during COVID-19 outbreak: an intercultural moderated mediation analysis. Pers Indiv Differ. 2021;177:110679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110679.

Article

Google Scholar

Antonovsky A. Health, stress, and coping. Jossey-Bass; 1979.

Google Scholar

Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass; 1987.

Google Scholar

Zapf D, Kern M, Tschan F, Holman D, Semmer NK. Emotion work: A work psychology perspective. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2021;8(1):139–72.

Article

Google Scholar

Peacock A. Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and vicarious trauma. Nurs ManAge. 2023;54(1). https://journals.lww.com/nursingmanagement/fulltext/2023/01000/compassion_satisfaction,_compassion_fatigue,_and.4.aspx

Rivera-Kloeppel B, Mendenhall T. Examining the relationship between self-care and compassion fatigue in mental health professionals: a critical review. Traumatology. 2023;29(2):163.

Article

Google Scholar

Sansó N, Galiana L, Oliver A, Tomás-Salvá M, Vidal-Blanco G. Predicting professional quality of life and life satisfaction in Spanish nurses: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Pub Health and Public Health. 2020;17(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124366.

Kong F, Gong X, Sajjad S, Yang K, Zhao J. How is emotional intelligence linked to life satisfaction? The mediating role of social support, positive affect and negative affect. J Retailing Happoness Stud. 2019;20:2733–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-00069-4.

Article

Google Scholar

Harris JI, Winskowski AM, Engdahl BE. Types of workplace social support in the prediction of job satisfaction. The Career Devel Q. 2007;56(2):150–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2007.tb00027.x.

Article

Google Scholar

Browning BR, McDermott RC, Scaffa ME. Transcendent characteristics as predictors of Counselor professional quality of life. J Ment Health counselling. 2019;41(1):51–64. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.1.05.

Article

Google Scholar

Duarte J. Professional quality of life in nurses: contribution for the validation of the Portuguese version of the professional quality of life scale-5 (ProQOL-5). Analise PsicoLogica. 2017;35. https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1260.

Tran ANP, To QG, Huynh V-AN, Le KM, To KG. Professional quality of life and its associated factors among Vietnamese doctors and nurses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):924. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09908-4.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Yılmaz G, Üstün B. Sociodemographic and professional factors influencing the professional quality of life and post-traumatic growth of oncology nurses*. J Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;10(4):241–50. https://doi.org/10.14744/phd.2019.43255.

Article

Google Scholar

Ball HL. Conducting online surveys. J Hum LAct. 2019;35(3):413–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419848734.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Thompson CB, Panacek EA. Research study designs: Non-experimental. Air Med J. 2007;26(1):18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2006.10.003.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Vogt WP. The dictatorship of the problem: Choosing research methods. Methodol Innov Online. 2008;3(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.4256/mio.2008.0006.

Article

Google Scholar

NSW Government. NSW health workforce Data. 2023. https://www.psc.nsw.gov.au/assets/psc/PSC-2023-Workforce-Profile-Report.pdf. NSW Public Commission.

Galiana L, Oliver A, Arena F, Simone GD, Tomas JM, Vidal-Blanco G, Munoz-Martinez I, Sanso N. Development and validation of the short professional quality of life scale based on versions IV and V of the professional quality of life scale. Health And Qual Of Life Outcomes. 2020;18:364. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01618-3.

Article

Google Scholar

Wong C-S, Law KS. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: an exploratory study. Leadersh Q. 2002;13(3):243–74. https://doi.org.ezproxy.brunel.ac.uk/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1

Lee J, Miller SE, Bride BE. Development and initial validation of the self-care practices scale. Soc Work. 2020;65(1):21–28. https://doi.org.ezproxy.brunel.ac.uk/10.1093/sw/swz045.

Cook-Cottone CP, Guyker WM. The development and validation of the mindful self-care scale (MSCS): An assessment of practices that support positive embodiment. Mindfulness. 2018;9:161–75.

Article

Google Scholar

Li Q, Xu L, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Huang Y. Exploring the self-care practices of social workers in China under the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Work And Policy. 2022;16(3):265–74. https://doi.org.ezproxy.brunel.ac.uk/10.1111/aswp.12266

Bloomquist K, Wood L, Friedmeyer-Trainor K, Kim H-W. Self-care and professional quality of life: Predictive factors among MSW practitioners. Adv Soc Work. 2015;16(2):292–311. https://doi.org/10.18060/18760.

Bur H, Bethelsen H, Moncada S, Nubling M, Dupre E, Demiral Y, Oudyk J, Kristensen TS, Llorens C, Navarro A, Lincke H-J, Bocerean C, Sahan S, Prhrt P, A., Copsoq Network I. The third version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Saf Health Work. 2019;10(4):482–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2019.10.002.

Article

Google Scholar

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. 3rd. The Guilford Press; 2022. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/jcu/detail.action?docID=6809031.

Google Scholar

Hayes AF, Coutts JJ. Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But …. Commun Methods and measures. 2020;14(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629.

Article

Google Scholar

Kalkbrenner MT. Alpha, omega, and H internal consistency reliability estimates: Reviewing these options and when to use them. Couns Outcome Res And evaluation. 2023;14(1):77–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2021.1940118.

Article

Google Scholar

Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr. 2018;85(1):4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100.

Article

Google Scholar

Ma J, Zeng Z, Fang K. Emotionally savvy employees fail to enact emotional intelligence when ostracized. Pers Indiv Differ. 2021;185:111250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111250.

Article

Google Scholar

Singh J, Karanika-Murray M, Baguley T, Hudson J. A systematic review of job demands and resources associated with compassion fatigue in mental health professionals. Int J Environ Res Pub Health And Public Health. 2020;17(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17196987.

Kim HJ, Hur W-M, Moon T-W, Jun J-K. Is all support equal? The moderating effects of Supervisor, coworker, and organizational support on the link between emotional labor and job performance. BRQ Bus Res Q. 2017;20(2):124–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2016.11.002.

Article

Google Scholar

Ormiston HE, Nygaard MA, Apgar S. A systematic review of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue in teachers. Sch Ment Health. 2022;14(4):802–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09525-2.

Article

Google Scholar

Hunsaker S, Chen H-C, Maughan D, Heaston S. Factors that influence the development of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in emergency department nurses. J Nurs scholarsh. 2015;47(2):186–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12122.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Sanchez-Gomez M, Sadovyy M, Breso E. Health-care professionals amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: how emotional intelligence may enhance work performance traversing the mediating role of work engagement. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184077.

Alonazi WB. The impact of emotional intelligence on job performance during COVID-19 crisis: a cross-sectional analysis. Phychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13(null):749–57. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S263656.

Article

Google Scholar

Mackay SJ, Baker R, Collier D, Lewis S. A comparative analysis of emotional intelligence in the UK and Australian radiographer workforce. Radiography. 2013;19(2):151–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2012.11.005.

Article

Google Scholar

Shah DK. WLEIS as a measure of emotional intelligence of healthcare professionals: a confirmatory factor analysis. J Health Manag. 2022;24(2):268–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/09720634221088057.

Article

Google Scholar

Sun H, Wang S, Wang W, Han G, Liu Z, Wu Q, Pang X. Correlation between emotional intelligence and negative emotions of front-line nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic: a cross-sectional study. J Clin nursing. 2021;30(3–4):385–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15548.

Article

Google Scholar

Weng H-C, Hung C-M, Liu Y-T, Cheng Y-J, Yen C-Y, Chang C-C, Huang C-K. Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction. Med Educ. 2011;45(8):835–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03985.x.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Bhullar N, Schutte NS, Malouff JM. Associations of individualistic-collectivistic orientations with emotional intelligence, mental health, and satisfaction with life: a tale of two countries. Individual Differences Res. 2012;10(3).

Gunkel M, Schlagel C, Engle RL. Culture’s influence on emotional intelligence: An empirical study of nine countries. J Int Manag. 2014;20:256–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2013.10.002.

Article

Google Scholar

Foster K, Fethney J, McKenzie H, Fisher M, Harkness E, Kozlowski D. Emotional intelligence increases over time: A longitudinal study of Australian pre-registration nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;55:65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.05.008.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Cary H. A review of factors influencing employee retention within the HealthCare workforce. 2024.

Sybert QM. Healthcare workers with attitude: COVID-19 Pandemic affects their Work-related attitudes. 2024.

Weidman AJ. Establishing a sustainable healthcare delivery workforce in the wake of COVID-19. J Health Care Manag. 2022;67(4):234–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/JHM-D-22-00100.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. p. xiii, 617.

Google Scholar

Goncher ID, Sherman MF, Barnett JE, Haskins D. Programmatic perceptions of self-care emphasis and quality of life among graduate trainees in clinical psychology: The mediational role of self-care utilization. Train And Educ In Profesional Phychol. 2013;7(1):53–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031501.

Article

Google Scholar

Eaves T, Mauldin L, Megan CB, Robinson JL. The professional is the personal: A qualitative exploration of self-care practices in clinical infant mental health practitioners. J Soc Service Res. 2020;47(3):369–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1817228.

Article

Google Scholar

Zeidner M, Mathews G, Olenik Shemesh D. Cognitive-social sources of wellbeing: Differentiating the roles of coping style, social support and emotional intelligence. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17:2481–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9703-z.

Article

Google Scholar

Cho H, Lee D. Effects of affective and cognitive empathy on compassion fatigue: Mediated moderation effects of emotion regulation capability. Pers Indiv Differ. 2023;211:112264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112264.

Article

Google Scholar

Huang X, Chan SCH, Lam W, Nan X. The joint effect of leader-member exchange and emotional intelligence on burnout and work performance in call centers in China. Int J Hum Resour MAn. 2010;21(7):1124–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585191003783553.

Article

Google Scholar

Psilopanagioti A, Anagnostopoulos F, Mourtou E, Niakas D. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and job satisfaction among physicians in Greece. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):463. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-463.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Barnett MD, Hays KN, Cantu C. Compassion fatigue, emotional labor, and emotional display among hospice nurses. Death Stud. 2022;46(2):290–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1699201.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Pekaar KA. Self- and other-focused emotional intelligence. 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/1765/116478.

Pekaar KA, Bakker AB, van der Linden D, Born MP. Self- and other-focused emotional intelligence: development and validation of the Rotterdam emotional intelligence scale (REIS). Pers Indiv Differ. 2018;120:222–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.045.

Article

Google Scholar

Asensio-Martínez Á, Leiter MP, Gascón S, Gumuchian S, Masluk B, Herrera-Mercadal P, Albesa A, García-Campayo J. Value congruence, control, sense of community and demands as determinants of burnout syndrome among hospitality workers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2019;25(2):287–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2017.1367558.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Nahum-Shani I, Henderson MM, Lim S, Vinokur AD. Supervisor support: Does supervisor support buffer or exacerbate the adverse effects of supervisor undermining? J Appl psychol. 2014;99(3):484–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035313.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Kim N, Kang YJ, Choi J, Sohn YW. The crossover effects of Supervisors’ workaholism on subordinates’ turnover intention: the mediating role of two types of job demands and emotional exhaustion. Int J Environ Res Pub Health And Public Health. 2020;17(21):7742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217742.

Article

Google Scholar

Tucker MK, Jimmieson NL, Bordia P. Supervisor support as a double-edged sword: Supervisor emotion management accounts for the buffering and reverse-buffering effects of supervisor support. Int J Stress Manag. 2018;25(1):14–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000046.

Article

Google Scholar

Charoensukmongkol P, Moqbel M, Gutierrez-Wirsching S. The role of coworker and supervisor support on job burnout and job satisfaction. J Educ Chang Adv Manag Res. 2016;13(1). https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-06-2014-0037.

Gillet N, Morin AJ, Fouquereau E. A person-centered perspective on work behaviors. Curr Phychol. 2023;42(32):28527–48.

Article

Google Scholar

Choi JH, Miyamoto Y. Cultural differences in self-rated health: the role of influence and adjustment. Jpn Psychol Res. 2022;64(2):156–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12405.

Article

Google Scholar

Eriksson M, Ghazinour M, Hammarström A. Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: What is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Soc Theor Health. 2018;16(4):414–33. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-018-0065-6.

Article

Google Scholar

NSW Government. (People matter, NSW Public Sector employee survey 2024, central coast local health district. 2024. https://files.dcu.nsw.gov.au/dpc/pmse2024/Health/Central%20Coast%20Local%20Health%20District.pdf.