Introduction

Psoriasis is recognized as a chronic, relapsing skin disorder that is mediated by immune and inflammatory processes.1 It is characterized by abnormal proliferation of keratinocytes, infiltration of immune cells, microvascular lesions, and activation of proinflammatory cytokine cascades.2 Additionally, the interaction between dendritic cells and T cells has been implicated in the onset and progression of psoriasis.3,4 The trends of current research have focused predominantly on immune cell dynamics, while investigations pertaining to microvascular involvement have been comparatively limited. Despite advancements in targeted biologic therapies, 30–50% of patients exhibit inadequate responses or develop resistance to these treatments.5 These findings underscore the need for further exploration of novel pathogenic mechanisms underlying this disease. These findings suggest the need to explore new pathogenesis mechanisms.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) considers that blood stasis persists throughout the entire occurrence and development process of psoriasis.6 Modern research has demonstrated that pathological manifestations, including vascular endothelial injury and platelet dysfunction, are present in both psoriasis and BSS.7,8 Psoriasis with BSS has been recognized as a clinical syndrome,9,10 primarily manifesting as skin microcirculatory dysfunction and aggravated skin inflammation. It is characterized by dark red skin lesions, vascular stasis, and microcirculatory disturbances; these phenotypes are closely associated with angiogenesis and platelet activation.11 Compared with other psoriasis patients, psoriasis patients with BSS exhibit more severe skin lesions, including exacerbated chronic inflammation,12,13 elevated angiogenic factors, metabolic disorders,14 and abnormal immune cell infiltration.14 Animal models have further confirmed that psoriasis in BSS mice results in more severe skin lesions.12 However, the specific pathological mechanism of skin lesion deterioration in psoriasis patients with BSS has remained unclear.

The function of platelets has transcended the traditional scope of hemostasis and coagulation; platelets have been redefined as effector cells with immunomodulatory activity that are deeply involved in inflammatory responses.15 Studies have suggested that activated platelets can exacerbate inflammatory responses in psoriasis;16 however, platelet dysfunction has been closely associated with the occurrence and development of psoriasis.17–21 Multiomics studies have consistently shown11,14,22 that PAF expression is significantly increased in the peripheral blood of psoriasis patients with BSS, suggesting that PAF may serve as a potential biomarker for psoriasis with BSS. Activated platelets release inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β and TGF-β, which amplify skin inflammation and imbalance between vascular injury and repair through immune cell cascades.23,24 However, whether platelets act as the core hub connecting blood stasis and psoriasis inflammation has not been elucidated.

Clopidogrel is a P2ry12 receptor antagonist; it irreversibly blocks the binding of ADP to the P2RY12 receptor on the surface of platelets, inhibits the activation of the GPIIb/IIIa complex, and thereby effectively prevents the final pathway of platelet aggregation. It is widely used in cardiovascular diseases.25 No study has systematically evaluated the multidimensional efficacy of clopidogrel in psoriasis with BSS animal models.

Thus, we speculate that platelet activation is the key factor exacerbating skin lesions in psoriasis with BSS and is the core hub connecting blood stasis and psoriasis inflammation; blocking platelet activation and aggregation can alleviate skin lesions in psoriasis with BSS, possibly related to regulating the P2ry12/GPIIb/IIIa axis.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Instruments

IMQ cream (Cat: H20030128) was obtained from Sichuan Mingxin Lidi Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China). Paquinimod (Cat: S9963) was sourced from Selleck Chemicals LLC.(Houston, Texas, United States). Clopidogrel (Cat: HJ20171237) was procured from Sanofi (Hangzhou) Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China). Epinephrine hydrochloride (Cat: H42021700) was acquired from Yuan Da Pharmaceutical (China) Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, Hubei Province, China). BCA protein assay reagents (Cat: 23227) were supplied by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). The antibodies utilized for Western blotting and immunohistochemistry included anti-CD62P (Cat: 60322-1-Ig) from Proteintech Group, Inc. (Wuhan, Hubei Province, China), PAFR antibody (Cat: DF13866) from Affinity Biosciences. (Liyang, Jiangsu Province, China), and β-actin (Cat: S7723) from Cell Signaling Technology.(Danvers, MA, USA) RIPA buffer (Cat: 9806S), goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Cat: 7074S), and rabbit (DA1E) mAb IgG XP® Isotype Control (Cat: 49077SF) were also obtained from Cell Signaling Technology.(Danvers, MA, USA). The phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Cat: CW2383S), additional phosphatase inhibitors (Cat: CW2200S), and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Cat: CW0049M) were obtained from Cowin Biotech. (Taizhou, Jiangsu, China). A protein-free rapid blocking solution (Cat: G2052-500ML) and Prestained Protein Marker Ⅹ(10–180 kDa) (Cat: G2091-250UL) was acquired from Servicebio (Wuhan, Hubei Province, China). TRIzol™ reagent (Cat: AG21102) and the SYBR Green Pro Taq HS premixed qPCR Kit II (Cat: AG11702) were purchased from Hunan Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Changsha, Hunan Province, China), EZBioscience® 4 × EZscript Reverse Transcription Mix II (with gDNA remover) (Cat: EZB-RT2GQ) was obtained from EZBioscience Biotechnology Corporation Limited (Shanghai, China).

Animals

Male SD rats, aged 8 weeks and averaging 280 g in weight, were acquired from Guangdong Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The animals were housed in the Experimental Animal Center of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine. The environmental conditions were regulated to maintain a temperature range of 22–24°C, with the relative humidity set between 45% and 55% and a light/dark cycle of 12 hours each. Throughout the duration of the experiment, the rats were provided unrestricted access to a standard laboratory diet and drinking water. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (Approval No: 2023136), and all procedures adhered to the 3R principles and ARRIVE guidelines of animal research ethics.

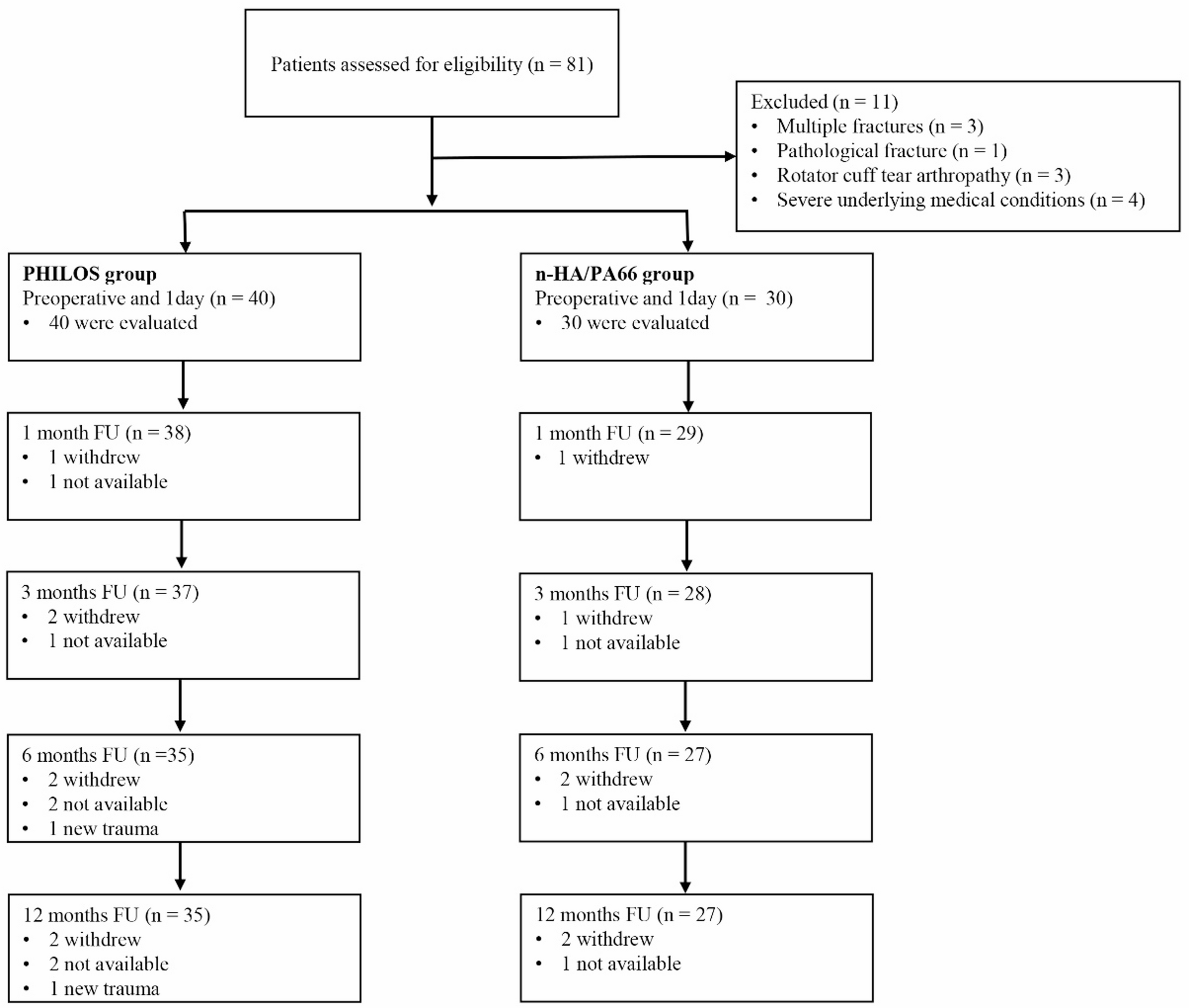

Establishment of a Rat Model of Psoriasis with BSS

Twenty-four male SD rats were randomly divided into 4 groups (n=6/group). The modeling procedure spanned a total duration of 21 days. The control group received no treatment. The IMQ group received no treatment during the first 14 days, followed by a daily topical administration of 5% imiquimod cream (150 mg/day) during the subsequent 7 days. The BSS group received no treatment during the first 7 days, after which they were subjected to daily immersion in ice–water baths (0–4°C, 15 minutes per day) for 14 days. On day 21, this group was administered two subcutaneous injections of adrenaline (0.8 mg/kg per injection) at 6-hour intervals. The BSS+IMQ group underwent daily morning ice–water baths (15 minutes per day) starting from day 1; from days 14 to 21, they additionally received daily topical applications of 5% imiquimod cream (150 mg/day) in the afternoon. On day 21, this group was also given adrenaline injections following the same protocol as the BSS group. Rat body weight and dorsal skin changes were monitored daily, and lesion severity was assessed using the PASI (scores ranging from 0 to 12, based on erythema, thickening, and scaling). The construction process of this experimental model lasted for 21 days. On the 22, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (30mg/kg), euthanized by cervical dislocation, and blood and skin samples were collected (Figure 1A).

|

Figure 1 Increased severity of skin lesions in rats with psoriasis and BSS compared to rats with psoriasis. (A) Animal modeling intervention process. (B) Dorsal skin appearance. (C) PASI score. (D) Body weight changes over time. (E and F) Spleen index and Spleen weight. (G) Epidermal Area. (H–M) Relative mRNA levels of CCL2, CCL20, CXCL10, CXCL1, S100A8 anS100A9 in lesions. (N and O). Neutrophil and lymphocyte proportions (CBC). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 versus Control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 versus IMQ.

|

An additional 18 male SD rats were prerandomized into 3 groups (n=6/group). The control group received no treatment. The BSS+IMQ group underwent daily ice–water baths (days 1–21), topical application of imiquimod cream (150 mg/day) on days 14–21, The BSS+IMQ + clopidogrel group underwent the same modeling procedure as the BSS+IMQ group and was administered clopidogrel (10 mg/kg/day) by oral gavage daily from days 14 to 21. The construction process of this experimental model lasted for 21 days. On day 22, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (30mg/kg), and blood and skin samples were collected.

Platelet Isolation

Three milliliters of blood from the inferior vena cava were collected into a centrifuge tube containing 600 μL of 3.8% sodium citrate. The blood was mixed with Tyrode’s solution at a 1:1 ratio and centrifuged at 200 × *g* for 10 minutes to obtain the PRP supernatant. The collected supernatant was mixed with ACD (PRP/9, μL) and apyrase [(PRP + ACD)/2500, μL] and then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 min, after which the supernatant was discarded. The platelets were resuspended in Tyrode’s solution and incubated at 37°C for 30–60 minutes for flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometry

CD62P antibody was added to a round-bottom 96-well plate and protected from light. Subsequently, 50 µL of each platelet mixture was transferred into the designated well, mixed thoroughly via a pipette, incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes, and shielded from light. Following this incubation period, 200 µL of 2% PFA was added to each well to facilitate fixation, after which the samples were analyzed via a flow cytometer.

Microcirculation Perfusion Measurement

The PeriCam PSI system is a noninvasive, two-dimensional imaging apparatus that employs LASCA technology to evaluate blood perfusion in peripheral tissues. Blood perfusion in the ears, hind limbs, and tails of the rats—defined as regions of interest (ROIs)—was measured via the PeriCam PSI system to evaluate microcirculation. Anesthetized rats were placed on the detection platform, the laser was activated, and after signal stabilization, data were acquired for one minute via PIMSoft (v1.5).

Hemorheology and Whole-Blood Analysis

Blood (2.5 mL) was obtained from the abdominal aorta of each rat and subsequently transferred into a vacuum blood collection tube containing sodium heparin. A blood rheometer was used to assess parameters such as blood flow resistance, erythrocyte aggregation, and plasma viscosity across various shear rates (10s−¹, 50s−¹, 200s−¹). Additionally, 100 μL of whole blood, which included EDTAK2 as an anticoagulant, was analyzed via a fully automated five-class animal blood cell analyzer for comprehensive blood analysis.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

Skin tissue, vascular tissue, and spleen tissue were preserved in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 48 hours. These samples were subsequently dehydrated via an automated dehydrator, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into thin slices measuring 4 µm. Following a series of processes, including dewaxing, staining, and dehydration, the sections were air-dried and mounted. The structural characteristics of the skin, blood vessels, and spleen were examined via a digital pathology scanner.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

After paraffin embedding and sectioning of the rat skin, vascular, and spleen tissues, the sections were dewaxed with xylene and placed in citrate buffer for antigen retrieval via the microwave method. Next, 3% hydrogen peroxide was added for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Five percent goat serum was added for blocking for 1 h, and then primary antibodies against PAFR, CD34, vWF, and VEGFA were added. The samples were placed in a humidified chamber overnight at 4°C. After rewarming, HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody was added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were developed with DAB. The samples were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through a graded series of 95% ethanol and absolute ethanol, mounted with neutral gum, and brown‒yellow positive signals were observed via a digital pathology scanner.

RT‒qPCR

Thirty milligrams of rat skin tissue was added to homogenization beads, 1 mL of TRIzol reagent was added, the mixture was homogenized, and total RNA was extracted. cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the reverse transcription kit. The synthesized cDNA was amplified using an amplification reaction kit. After the reaction, the specificity of the PCR was determined on the basis of the melting curve. GAPDH was used as the internal reference, and the relative expression levels of the target genes were calculated using the 2ΔΔCt method and statistically analyzed. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 The Primer Sequences of Rat Employed in This Research

|

Western Blotting (WB)

Fifty milligrams of rat skin tissue was weighed, and total protein was extracted from the skin samples via RIPA buffer supplemented with 1% phosphatase and protease inhibitors. The protein concentration was determined via the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein (40 µg) were separated via 8% SDS‒PAGE and transferred to 0.45 µm PVDF membranes. Following a 15-minute blocking period with rapid blocking solution, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against CD62P, PAFR, and β-actin. Detection was performed via the use of an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent, and exposure was conducted with the e-Blot system. The gray values of the bands were analyzed via ImageJ software.

Network Pharmacology Analysis

Clopidogrel targets were obtained from PubChem, SwissTargetPrediction, and PharmMapper. Psoriasis and PAF-related targets were retrieved from GeneCards, OMIM, and DisGeNET using a relevance score ≥ 1. Intersections of clopidogrel–psoriasis and clopidogrel–PAF targets were identified and used to construct networks in Cytoscape. Topological analysis was performed using NetworkAnalyzer. PPI networks were built via STRING (confidence > 0.7) and analyzed with CytoNCA to identify key targets. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were conducted using clusterProfiler in R. Molecular docking of key targets was performed with AutoDock Vina. Detailed procedures are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Data Analysis

The results are presented as the mean values ± SEMs. The data were analyzed via one-way ANOVA with GraphPad Prism 10.1.2, and a P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Increased Severity of Skin Lesions in Rats with Psoriasis and BSS Compared with That in Rats with Psoriasis

The experimental design is illustrated in Figure 1A. Compared with those in the control and BSS groups, the rats in the IMQ group and the IMQ+BSS group presented marked erythema, skin thickening, and desquamation, whereas those in the IMQ+BSS group presented more pronounced symptoms (Figure 1B). Compared with those in the control group, the subcutaneous blood vessels in the other experimental groups presented varying degrees of thickening, tortuosity, and increased branching, with the most significant changes observed in the IMQ+BSS group, followed by those in the BSS group (Supplementary Figure 1A). These observations confirmed the successful establishment of the psoriasis model with concomitant BSS. The PASI scores correlated with the observed alterations in the skin lesions (Figure 1C). During the modeling phase, the IMQ+BSS group presented a slower rate of weight gain than the control, BSS, and IMQ groups did (Figure 1D). In terms of splenic morphology, the rats in the IMQ group presented significant splenomegaly (Supplementary Figure 1B), resulting in an elevated spleen index, whereas those in the BSS group presented a significantly reduced spleen index, with the IMQ+BSS group showing the next lowest index (Figure 1E and F).

HE staining revealed alterations in the dorsal skin of the rats (Figure 1G). Compared with the control group, the BSS group did not exhibit any significant changes. Conversely, both the IMQ group and the IMQ+BSS group presented distinct characteristics associated with psoriasis. Notably, the IMQ+BSS group presented more severe pathological features than did the IMQ group, including epidermal acanthosis and club-shaped hyperplasia (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Alterations in Chemokines and Inflammatory Mediators in Psoriasis Rats and Psoriasis Rats with BSS

The results from RT‒qPCR analysis indicated that, compared with those in the IMQ group, the mRNA expression levels of the chemokines CXCL10 and CCL2 in the skin tissues of the IMQ+BSS group were markedly elevated (Figure 1H–K). These findings suggest an enhanced inflammatory response and increased immune cell infiltration in the IMQ+BSS rat model.

The RT‒qPCR results demonstrated that the mRNA levels of the inflammatory mediator S100A9 in the skin tissues of the IMQ+BSS group were significantly greater than those in the IMQ group, while S100A8 also showed an upward trend (Figure 1L and M). Furthermore, whole blood analysis indicated that the NEUT and LYM proportions were notably greater in the IMQ+BSS group than in the control group, with varying degrees of elevation observed (Figure 1N and O).

Microcirculation and Hemorheology in Psoriasis Rats and Psoriasis Rats with BSS

Microcirculatory perfusion analysis revealed a significant reduction in blood flow in the ears and legs of the IMQ+BSS group compared with those of the Control and IMQ groups. The BSS group presented the second lowest perfusion level (Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure 1D). The IMQ+BSS group presented notable increases in the shear rate (10 s−¹), medium shear rate (50 s−¹), high shear rate (200 s−¹), and plasma viscosity index (Figure 2A), suggesting significant increases in blood viscosity and flow resistance. Furthermore, whole blood analysis revealed that hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (HCT), and Red Blood Cell (RBC) counts were notably greater in the BSS group than the other three groups (Figure 2B).

|

Figure 2 Blood stasis manifestations in rats with psoriasis and BSS were more severe than in rats with psoriasis. (A) Whole blood flow resistance analysis. (B) Hb, RBC, and HCT (CBC). (C) ROI values for circulatory perfusion in ears, leg, and tail. (D) Blood vessel HE staining. (E) IHC detection of vWF expression in rat blood vessel. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 versus Control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, versus IMQ.

|

Vascular Structural Changes in Psoriatic Rats and Psoriatic Rats with BSS

Histological examination via HE staining revealed alterations in the abdominal aortas of the rats. Notably, the IMQ+BSS group presented a significant increase in vascular thickness compared with both the Control and IMQ groups (Figure 2D). The expression of vWF, which is known to increase in response to vascular activation or injury and plays a role in platelet adhesion, was assessed through immunohistochemistry. The results indicated that vWF protein expression was elevated in the IMQ+BSS group relative to the control and IMQ groups, with the BSS group showing the next highest levels (Figure 2E). In brief, the findings suggest that vascular endothelial damage is more pronounced in the IMQ+BSS group than in the IMQ group.

Platelet Activation in Psoriasis Rats and Psoriasis Rats with BSS

CD62P is an established marker of platelet activation. PAFR is the receptor for platelet activating factor. PTGS1 serves as the primary enzyme responsible for the synthesis of TXA2 in platelets, which is a critical factor in promoting platelet aggregation. The RT‒qPCR results indicated that the mRNA expression level of PTGS1, CD62P, PAFR was significantly elevated in the IMQ+BSS group compared with both the control and BSS groups (Figure 3A–D). Furthermore, IHC analysis was employed to evaluate the expression of PAFR in the skin tissue of the rats. Compared with that in the control group, PAFR-positive expression was significantly greater in the BSS group, and PAFR-positive expression was even greater in the IMQ+BSS group than in the IMQ group (Figure 3E and F). Additionally, CD62P and PAFR were detected by WB. The findings revealed that the protein levels of PAFR and CD62P were markedly greater in the IMQ+BSS group than in the control and BSS groups (Figure 3G–I and Supplementary Figures 3–5). Taken together, these findings indicate that the platelet activation ratio was significantly increased in the rat model of psoriasis with BSS.

|

Figure 3 Platelet activation in rats with psoriasis and BSS was more pronounced than in rats with psoriasis. (A–D) Relative mRNA levels of PAFR, Selp, PTGS1 and PTGS2 in lesions. (E and F) IHC detection of PAFR expression in rat skin. (G–I) Western blot analysis of PAFR and CD62P protein levels in rat skin. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 versus Control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus IMQ.

|

Efficacy of Clopidogrel in Alleviating Skin Lesions in Pregnant Rats with BSS

In this study, we administered the platelet aggregation inhibitor clopidogrel (10 mg/kg/d) to rats with IMQ+BSS via oral gavage to assess the impact of platelet activation and aggregation on the skin lesions observed in this model (Supplementary Figure 2A). Compared with the control group, the IMQ+BSS group presented pronounced psoriasis-like skin lesions; however, these lesions were significantly greater in the clopidogrel-treated group (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the subcutaneous blood vessels in the dorsal region of the IMQ+BSS group displayed marked thickening, tortuosity, and increased branching relative to those in the control group (Figure 4A). The PASI scores were in line with the alterations in the skin lesions (Figure 4B). Histological examination via HE staining revealed that the IMQ+BSS group presented more pronounced pathological features, including epidermal thickening, whereas the clopidogrel group presented a significant reduction in the epidermal area (Figure 4C and D).

|

Figure 4 Clopidogrel alleviates skin lesions in rats with psoriasis and BSS. (A) Dorsal skin appearance and Subcutaneous blood vessel morphology in rats. (B) PASI score. (C and D) Skin HE staining. (E–G) Relative mRNA levels of CCL20, S100A8 and S100A9 in lesions. (H and I) Neutrophil and lymphocyte proportions (CBC). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 versus Control. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 versus IMQ+BSS.

|

Clopidogrel Can Improve the Effects of Chemokines and Inflammatory Mediators in Psoriatic Rats with BSS

The RT‒qPCR results indicated that, compared with those in the control group, the mRNA expression levels of CCL20, S100A8, and S100A9 in the skin tissues of the rats in the IMQ+BSS group were markedly elevated (Figure 4E–G). Furthermore, the clopidogrel treatment group presented significant reductions in the expression of CCL20, S100A8, and S100A9 (Figure 4E–G). Additionally, whole-blood analysis revealed that, compared with the IMQ+BSS group, the clopidogrel group presented significant decreases in the proportions of NEUTs and LYMs (Figure 4H and I).

Clopidogrel Enhances Microcirculation and Hemorheological Parameters in Psoriatic Rats with BSS

The results of microcirculation perfusion assessments indicated that, in comparison with those in the Control group, there was a significant reduction in blood flow within the ears and hind limbs of the IMQ+BSS group. Conversely, the clopidogrel-treated group demonstrated varying degrees of improvement in terminal circulation (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure 2B). Hemorheological analyses revealed that the IMQ+BSS group presented elevated shear rates (10 s−¹), medium shear rates (50 s−¹), high shear rates (200 s−¹), and PVs than did the control group. The administration of clopidogrel resulted in a reduction in these parameters (Figure 5A), suggesting that clopidogrel effectively decreases blood viscosity and flow resistance in the IMQ+BSS model of rats.

|

Figure 5 Clopidogrel alleviates Blood stasis manifestations in rats with psoriasis and BSS. (A) Whole blood flow resistance analysis. (B) ROI values for circulatory perfusion in ears, leg, and tail. (C) Spleen and blood vessel HE staining. (D) Thickness of vessel wall. (E and F) IHC detection of VEGFA expression in rat skin. (G and H) IHC detection of CD34 expression in rat skin. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus Control. #P < 0.05 versus IMQ+BSS.

|

Clopidogrel Ameliorates Intrasplenic Erythrocyte Accumulation and Vascular Wall Thickening in Rats with Psoriasis and BSS

HE staining revealed increased vascular wall thickness in the IMQ+BSS group compared with the control group, whereas clopidogrel reduced this thickening (Figure 5D and Supplementary Figure 2C). Splenic examination revealed substantial erythrocyte stasis in the IMQ+BSS red pulp sinuses compared with the control, whereas clopidogrel significantly decreased stasis (Figure 5C).

Clopidogrel Reduces VEGFA and CD34 Expression in Psoriatic Rats with BSS

VEGFA is a proangiogenic marker of active angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry revealed significantly increased VEGFA expression in the IMQ+BSS group compared with the control group, whereas clopidogrel treatment reduced VEGFA levels (Figure 5E and F). CD34, a vascular endothelial marker, identifies dermal microvessels. The new capillary density in the dermis was greater in the IMQ+BSS group than in the control group but decreased with the addition of clopidogrel (Figure 5G and H). These results indicated that clopidogrel inhibited microvascular neovascularization in IMQ+BSS-treated rat skin.

Network Pharmacology Predicts the Mechanism of Clopidogrel in Treating Psoriatic Rats with BSS

Construction of Clopidogrel-Psoriatic and Clopidogrel-PAF Interaction Networks

Screening targets retrieved from the PubChem database via the search term “clopidogrel” with Probability ≥0 and Z score ≥0.5 yields 246 targets. Searching the GeneCards, Omim, and DisGeNET databases with “psoriasis” and “PAF” as keywords and filtering for a relevance score ≥1 yields 1436 psoriasis targets and 4900 PAF targets. After merging and removing duplicates, the intersection of clopidogrel and psoriasis yielded 83 common targets (Figure 6A), whereas the intersection of clopidogrel and PAF yielded 180 common targets (Figure 6B).

|

Figure 6 Network pharmacology and molecular docking identify P2ry12 and GPIIb/IIIa as a potential target of clopidogrel for psoriasis with BSS. (A) Psoriasis-Clopidogrel target intersection. (B) PAF-Clopidogrel target intersection. (C) PPI network of Clopidogrel-Psoriasis shared targets. (D) PPI network of Clopidogrel-PAF shared targets. (E) Core targets screened from Clopidogrel-Psoriasis. (F) Core targets screened from Clopidogrel-PAF. (G) GO enrichment for Clopidogrel-Psoriasis targets. (H). GO enrichment for Clopidogrel-PAF targets. (I) KEGG enrichment for Clopidogrel-Psoriasis targets. (J) KEGG enrichment for Clopidogrel-PAF targets. (K and L) Clopidogrel-core target docking scores. (M–P) Molecular docking schematics for P2ry12/PTGS1/GPIIIa/SRC with Clopidogrel.

|

Protein‒protein Interaction (PPI)

Importing the clopidogrel-psoriasis and clopidogrel-PAF intersection targets into the STRING database to construct the original PPI network at a maximum confidence of 0.7 generates a Cytoscape network file (Figure 6C and D). Importing the network TSV file into Cytoscape for visualization and performing topological analysis via the CytoNCA plugin with cyclic median screening based on six topological parameters (betweenness, closeness, degree, eigenvector, LAC, and network) identifies core targets for clopidogrel in treating psoriasis: SRC, CYP1B1, DPP4, PLAU, PTGS1, etc. (Figure 6E), and core targets for clopidogrel in regulating platelet activation: CYP2D6, MPO, MAP2K1, P2RY12, PTGS1, etc. (Figure 6F).

GO and KEGG Analyses

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses indicate that clopidogrel treatment for psoriasis and clopidogrel regulation of PAF involve multiple biological processes, including oxidative stress and tissue proliferation/metabolism. Among the top ten GO and KEGG enrichment results for clopidogrel and psoriasis (Figure 6G and I), “Arachidonic acid metabolism” was present. In platelets, arachidonic acid can be metabolized by cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) to generate thromboxane A₂ (TXA₂), promoting platelet activation and aggregation. Among the top twenty GO and KEGG enrichment results for clopidogrel and psoriasis, pathways including “platelet activation”, “blood coagulation”, “coagulation”, and “hemostasis” were involved (Figure 6H and J). These findings suggest that clopidogrel may treat psoriasis by regulating platelets.

Molecular Docking

Molecular docking studies are performed using protein structures (P2RY12, PTGS1, ITGB3, SRC) retrieved from the PDB database. The docking results (Figure 6K and L) show that among the clopidogrel-psoriasis target interactions, 13 have binding energies < -5 kcal/mol; among the clopidogrel-PAF interactions, 15 have binding energies < -5 kcal/mol. Specifically, the binding energy of clopidogrel with P2RY12 is -7.5 kcal/mol, and that with ITGB3 is -7.0 kcal/mol. This indicated a potential strong interaction and provided the structural basis for its selective binding to P2RY12 and antiplatelet aggregation effect (Figure 6M–P).

Clopidogrel Reduces Platelet Activation and Aggregation in Rats with Psoriasis and BSS

We used RT‒qPCR to verify the predicted targets from network pharmacology. Compared with those in the IMQ+BSS group, the mRNA expression levels of P2Y12 (P2RY12), itgb3 (GPIIIa), itga2b (GPIIb), GP1ba, Selp (P-selectin), PAFR, GP5 and GP9 were lower in the clopidogrel group (Figure 7A–H). P2RY12 is a membrane glycoprotein receptor on platelets that promotes platelet aggregation. GPIIIa combines with GPIIb to form the platelet membrane glycoprotein GPIIb/IIIa complex, which is the final common pathway for platelet aggregation. Flow cytometry further verified that the percentage of CD62P-activated platelets peaked in the IMQ+BSS group, and this proportion significantly decreased after clopidogrel intervention (Figure 7I and J). Immunohistochemical analysis of rat skin tissue revealed that platelet PAFR expression was significantly upregulated in the IMQ+BSS model group compared with the control group, whereas clopidogrel intervention markedly inhibited this increase in expression (Figure 7K and L).

|

Figure 7 Clopidogrel reduces platelet activation and aggregation in rats with psoriasis and BSS. (A–F) Relative mRNA levels of itgb3, itga2b, P2Y12, GPIba, GP5, GP9, in lesions. (G and H) Relative mRNA levels of Selp, and PAFR in lesions. (I and J) Flow cytometric detection of CD62P. (K and L) IHC detection of PAFR expression in rat skin. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 versus Control. #P < 0.05 versus IMQ+BSS.

|

In summary, multimethodological evidence confirms that clopidogrel ameliorates psoriasis with BSS by inhibiting platelet activation and aggregation, which is likely associated with the P2RY12/GPIIb/IIIa axis.

Discussion

Clinical and animal experiments indicate12 that psoriasis patients with BSS exhibit more severe skin lesions than psoriasis patients do, but exploration of its pathological mechanisms is lacking. Platelet activation is closely linked to psoriasis inflammation, and PAF represents a potential biomarker for psoriasis with BSS. However, whether platelet activation serves as the key factor exacerbating skin lesions in psoriasis patients with BSS requires investigation.

On the basis of these research gaps, this study established a model via an ice–water bath combined with epinephrine injection, revealing the critical role of platelet activation in aggravating psoriasis with BSS. This study systematically evaluated the potential mechanisms of clopidogrel in treating psoriasis with BSS through network pharmacology and proposed a novel strategy targeting platelet activation for psoriasis with BSS therapy. Psoriasis in BSS rats results in significantly aggravated skin lesions, hyperviscosity, microvascular pathology, and excessive platelet activation, confirming the hypercoagulable state and intensified inflammation observed clinically in psoriasis patients with BSS.11,12,14 Multiomics studies suggest PAF as a potential biomarker for psoriasis with BSS,22 while this experiment further proves that platelet activation acts as the core hub connecting blood stasis and inflammation exacerbation, aligning with recent findings identifying platelets as a key bridge linking inflammation and thrombosis.26 Clopidogrel irreversibly inhibits the P2ry12 receptor, significantly improving skin lesion severity, hemorheological abnormalities, and vascular damage in BSS rats. Mechanistically, on the basis of network pharmacology and experimental validation, we propose that clopidogrel suppresses the P2ry12/GPIIb/IIIa axis, blocks platelet release of PAF and P-selectin (CD62P), and inhibits platelet activation and aggregation, thereby reversing the feedback loop between blood stasis and inflammation.

The modeling method in this study optimizes existing IMQ+BSS-based approaches by establishing a composite model that simultaneously simulates psoriatic inflammation and blood stasis conditions. Specifically, it involves 14 days of ice–water baths followed by 7 days of ice–water baths combined with topical IMQ application, lasting 21 days in total. This method builds upon existing BSS models to establish a psoriasis model, aiming to simulate the clinical characteristics of blood stasis constitution as the pathogenic basis of psoriasis, aligning with chronic blood stasis pathogenesis. The psoriasis with BSS rat model developed in this study exhibited more severe skin lesions than did the psoriasis model in the following aspects. First, based on PASI score and H&E staining, the IMQ+BSS group rats exhibited more pronounced psoriasiform symptoms and increased epidermal areas. Second, as measured by hemorheology and microcirculation perfusion measurement, they demonstrated blood hyperviscosity and microcirculatory dysfunction. Finally, vascular alterations included increased branching, thickened vessel walls, and significantly elevated von Willebrand vWF expression. In addition, the observed increase in neutrophil ratio, upregulation of inflammatory mediators S100A8/A9, and elevated chemokines such as CCL20 in the model were highly consistent with the expression patterns seen in psoriatic patient lesions.27–29 The IMQ+BSS rat model concurrently displayed inflammatory responses of psoriasis and a state of blood stasis, providing a stable animal model with inherent characteristics for subsequent research.

Platelets are not only key cells involved in the hemostatic process, but also regulate immune responses.26,30 Research indicates that platelet activity levels directly correlate with psoriasis severity in patients. Activated platelets in psoriasis induce endothelial inflammation through COX-1.16 P-selectin released during platelet activation mediates platelet‒leukocyte adhesion, recruiting inflammatory cells to infiltrate the skin and establishing a vicious cycle between inflammation and platelet activation in psoriasis. Furthermore, severe psoriasis patients exhibit significantly increased susceptibility to vascular disease morbidity and mortality.17,31–33 Concurrently, platelets contribute to vascular injury and repair via diverse receptors, signaling pathways, and effector functions,34 forming a self-perpetuating loop between platelets and the vasculature. In this study, psoriasis with BSS rats not only presented aggravated skin lesions and a pro-thrombotic state but also presented significantly elevated PAFR expression and selp (P-Selectin, CD62P) mRNA levels in skin tissues. We propose that platelets act as the core hub connecting the blood stasis state and psoriatic inflammation: on the one hand, they release mediators such as P-selectin to induce inflammation and inflammatory cell adhesion; on the other hand, platelet activation and aggregation cause blood hyperviscosity and microcirculatory dysfunction, thereby exacerbating skin lesions in psoriasis patients with BSS. This aligns with clinical observations of hyperactive platelets and an elevated cardiovascular risk in psoriatic patients. Clopidogrel covalently binds to the P2ry12 receptor, blocking ADP binding to P2ry12, consequently reducing activation of the membrane glycoprotein GPIIb/IIIa.35 This inhibits platelet aggregation while simultaneously suppressing thrombus formation and pathological angiogenesis.36 It is commonly used for preventing and treating cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases such as stroke and myocardial infarction.37 However, no studies have investigated the role of clopidogrel in inflammatory skin diseases. This study systematically evaluated the efficacy of clopidogrel in a BSS animal model; we demonstrated that clopidogrel ameliorates psoriasiform skin lesions and the prothrombotic state, reducing the protein expression of the platelet activation markers CD62P and PAFR in skin tissues. We propose that clopidogrel improves skin lesions in psoriasis patients with BSS by reducing platelet activation and aggregation.

To investigate the specific mechanism by which clopidogrel ameliorates psoriasis with BSS, we performed network pharmacological analysis. GO and KEGG analyses revealed that the targets through which clopidogrel exerts its effects are significantly enriched in pathways such as “platelet activation” and “blood coagulation”. Molecular docking confirmed that clopidogrel has good binding ability with the P2ry12 (P2Y12) receptor and the GPIIIa (itgb3) receptor. The RT‒qPCR results indicate that clopidogrel decreases the mRNA levels of P2Y12, itgb3, and itga2b, among which GPIIb and GPIIIa noncovalently associate to form the GPIIb/IIIa complex. The activation of GPIIb/IIIa is the final common pathway for platelet aggregation. Therefore, we speculate that clopidogrel inhibits platelet aggregation and ameliorates skin lesions in psoriasis with BSS, which is associated with modulating the P2ry12/GPIIb/IIIa axis.

This study has limitations. The IMQ+BSS model is a valuable artificial construct that captures key pathologies of psoriasis with BSS but does not fully replicate the complex, chronic nature of the human disease, which arises from long-term genetic, immune, and environmental interactions. Moreover, the mechanism of platelet activation in this context remains unelucidated. Lastly, clopidogrel’s efficacy was shown in the IMQ+BSS model but not in the standard IMQ model, necessitating further proof.

In summary, this study establishes an animal model of BSS in psoriasis and reveals that platelet activation plays a key role in aggravating psoriatic lesions in this syndrome; inhibiting platelet aggregation improves these lesions.

Conclusion

Platelet activation plays a crucial role in exacerbating skin lesions in a rat model of psoriasis with BSS; inhibiting platelet activation and aggregation significantly ameliorates psoriasis with BSS.

Abbreviations

BSS, blood stasis syndrome; GO, gene ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; IMQ, imiquimod; PAFR, platelet-activating factor receptor; qRT‒PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase; HE, hematoxylin-eosin; IHC, immunohistochemistry; WBV, whole blood viscosity; WB, Western blotting; PASI, psoriasis area and severity index; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; P2Y12, purinergic receptor P2Y12; GPIIb-IIIa, glycoprotein IIb-IIIa; SD, Sprague Dawley; PRP, platelet-rich plasma; ACD, acid-citrate-dextrose; PAF, paraformaldehyde; LSCA, laser speckle contrast analysis; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NEUT, neutrophil; LYM, lymphocyte; RBC, red blood cell; vWF, von Willebrand factor; TXA2, thromboxane A2; PV, plasma viscosity; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; ADP, adenosine diphosphate.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The nucleotide sequence data generated in this study are available in the GenBank ((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) repository under database accession number [NM_053822.2], [NM_053587.2], [NM_013114.2], [NM_001429782.1], [NM_031530.1], [NM_139089.2], [NM_017043.4], [NM_017232.4], [NM_019233.2], [NM_001427035.1], [NM_022800.1],[NM_030845.2], [NM_022800.1], [NM_001109654.1], [NM_001031825.2], [NM_012795.3], [NM_153720.2]).

Ethics Approval

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (Approval No: 2023136).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all the help for this work.

Author Contributions

Hongyu Yue: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.; Haoran Mo: Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft; Haojie Su: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft; Zizhong Zeng: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft; Fanlu Liu: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; Chenjing Lei: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; Yue Sun: Validation, Writing-original draft; Tingyu Wang: Validation, Writing-original draft; Xiaorui Pi: Investigation, Writing-original draft; Li Li: Methodology, Writing-original draft; Jingjing Wu: Conceptualization, Writing-original draft; Ling Han: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. All authors took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82374313); Guangdong Province Science and Technology Planning Project (2020B1111100006, 2023B1212060063), State Key Laboratory of Dampness Syndrome of Chinese Medicine Special Fund (SZ2021ZZ29).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Liu S, Song S, Zhang Y, et al. Delivery of penetration-enhancing antioxidant polyphenol nanoparticles with Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharide microneedles for synergistic treatment of psoriasis. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2025;363:123777. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2025.123777

2. Sieminska I, Pieniawska M, Grzywa TM. The immunology of psoriasis-current concepts in pathogenesis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2024;66(2):164–191. doi:10.1007/s12016-024-08991-7

3. Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1475. doi:10.3390/ijms20061475

4. Ghoreschi K, Balato A, Enerbäck C, Sabat R. Therapeutics targeting the IL-23 and IL-17 pathway in psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):754–766. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00184-7

5. Strober BE, Blauvelt A, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. International psoriasis council psoriasis disease severity reclassification: update on validity, acceptance, and implementation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93(4):1154–1157. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.05.1445

6. Chen Y, Zhang Y. Interpretation of the pathological mechanism of blood stasis in traditional Chinese medicine in light of understanding of hypercoagulable states in modern medicine. Chin Med Nat Prod. 2025;5(01):30–34. doi:10.1055/s-0045-1806864

7. He Y, Jiang H, Du K, et al. Exploring the mechanism of Taohong Siwu Decoction on the treatment of blood deficiency and blood stasis syndrome by gut microbiota combined with metabolomics. Chin Med. 2023;18(1):44. doi:10.1186/s13020-023-00734-8

8. Xin QQ, Chen X, Yuan R, et al. Correlation of platelet and coagulation function with blood stasis syndrome in coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin J Integr Med. 2021;27(11):858–866. doi:10.1007/s11655-021-2871-2

9. Zou ZJ, Liu ZH, Gong MJ, Han B, Wang SM, Liang SW. Intervention effects of puerarin on blood stasis in rats revealed by a (1)H NMR-based metabonomic approach. Phytomedicine. 2015;22(3):333–343. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2015.01.006

10. Zhang X, Sheng N, Wang Z, et al. Exploring the mechanism of Carbonized Typhae Pollen in treating blood stasis syndrome through metabolic profiling: the synergistic effect of hemostasis without blood stasis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;351:120124. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2025.120124

11. Li L, Yao DN, Lu Y, et al. Metabonomics study on serum characteristic metabolites of psoriasis vulgaris patients with blood-stasis syndrome. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:558731. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.558731

12. Luo Y, Ru Y, Zhao H, et al. Establishment of mouse models of psoriasis with blood stasis syndrome complicated with glucose and lipid metabolism disorders. Evidence-Based Complem Altern Med. 2019;2019:6419509. doi:10.1155/2019/6419509

13. Yan JT, Wang QG, Liu XQ, et al. The immune status of patients with psoriasis vulgaris of blood-stasis syndrome and blood-dryness syndrome: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Annals Palliative Med. 2020;9(4):1382–1395. doi:10.21037/apm-19-432

14. Lu Y, Yan Y, Qi Y, et al. Analysis of microRNA expression in peripheral blood monocytes of three Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) syndrome types in psoriasis patients. Chin Med. 2020;15:39. doi:10.1186/s13020-020-00308-y

15. Maugeri N, Manfredi AA. Platelets as drivers of immunothrombosis in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2025;21(8):478–493. doi:10.1038/s41584-025-01276-z

16. Garshick MS, Tawil M, Barrett TJ, et al. Activated platelets induce endothelial cell inflammatory response in psoriasis via COX-1. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis Vasc Biol. 2020;40(5):1340–1351. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.119.314008

17. Fan Z, Wang L, Jiang H, Lin Y, Wang Z. Platelet dysfunction and its role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Dermatology. 2021;237(1):56–65. doi:10.1159/000505536

18. Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1073–1113. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

19. Nickoloff BJ, Qin JZ, Nestle FO. Immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007;33(1–2):45–56. doi:10.1007/s12016-007-0039-2

20. Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61909-7

21. Miller IM, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, Jemec GB. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6):1014–1024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.053

22. Liu Q, Wu DH, Han L, et al. Roles of microRNAs in psoriasis: immunological functions and potential biomarkers. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26(4):359–367. doi:10.1111/exd.13249

23. Liu X, Gorzelanny C, Schneider SW. Platelets in skin autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1453. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01453

24. Linge P, Fortin PR, Lood C, Bengtsson AA, Boilard E. The non-haemostatic role of platelets in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(4):195–213. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2018.38

25. Giacoppo D, Gragnano F, Watanabe H, et al. P2Y(12) inhibitor or aspirin after percutaneous coronary intervention: individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2025;389:e082561. doi:10.1136/bmj-2024-082561

26. Goto S, Oki M, Goto S. Platelet derived RNAs: a new regulatory marker for vascular inflammation? Cardiovasc Res. 2025;121:1308–1310. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaf124

27. Matsunaga Y, Hashimoto Y, Ishiko A. Stratum corneum levels of calprotectin proteins S100A8/A9 correlate with disease activity in psoriasis patients. J Dermatol. 2021;48(10):1518–1525. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16032

28. Wang WM, Wu C, Gao YM, Li F, Yu XL, Jin HZ. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, and other hematological parameters in psoriasis patients. BMC Immunol. 2021;22(1):64. doi:10.1186/s12865-021-00454-4

29. Bakic M, Klisic A, Karanikolic V. Comparative study of hematological parameters and biomarkers of immunity and inflammation in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Medicina. 2023;59(9):1622. doi:10.3390/medicina59091622

30. Hou J, Song Y, Xiao C, et al. Cloche/Npas4l is a pro-regenerative platelet factor during zebrafish heart regeneration. Dev Cell. 2025. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2025.06.015

31. Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the general practice research database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(8):1000–1006. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp567

32. Ogdie A, Kay McGill N, Shin DB, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a general population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(39):3608–3614. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx145

33. Chung WS, Lin CL. Increased risks of venous thromboembolism in patients with psoriasis. A nationwide cohort study. Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2017;117(8):1637–1643. doi:10.1160/th17-01-0039

34. Kaiser R, Escaig R, Nicolai L. Hemostasis without clot formation: how platelets guard the vasculature in inflammation, infection, and malignancy. Blood. 2023;142(17):1413–1425. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020535

35. Damman P, Woudstra P, Kuijt WJ, de Winter RJ, James SK. P2Y12 platelet inhibition in clinical practice. J Thrombosis Thrombolysis. 2012;33(2):143–153. doi:10.1007/s11239-011-0667-5

36. Patel RC, Thomas CD, Rossi JS, et al. CYP2C19 phenotype, P2Y(12) inhibitor selection, and clinical outcomes in patients on maintenance clopidogrel therapy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025;14(14):e041634. doi:10.1161/jaha.125.041634

37. Hardi H, Barinda AJ, Mahata LE, Fitrianti Z. CYP2C19 variability and clinical outcomes of clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors, and voriconazole in Southeast Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1572886. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1572886