- Australia’s central bank holds rates steady, warns of inflation risk Reuters

- Australian dollar braces for hawkish RBA, bond yields hit two-year high Business Recorder

- Reserve Bank holds interest rates amid warning on stubborn housing inflation realestate.com.au

- AUD/NZD slides to near 1.1440 as RBA holds OCR steady at 3.6%, as expected FXStreet

- The RBA decision highlights today’s Asia-Pacific calendar TradingView

Category: 3. Business

-

Australia's central bank holds rates steady, warns of inflation risk – Reuters

-

Australia central bank keeps rates at 3.6%, warns of inflation risk – Reuters

- Australia central bank keeps rates at 3.6%, warns of inflation risk Reuters

- Australian dollar braces for hawkish RBA, bond yields hit two-year high Business Recorder

- Reserve Bank makes final rate call for 2025 hrleader.com.au

- Reserve Bank holds interest rates amid warning on stubborn housing inflation realestate.com.au

- AUD/NZD slides to near 1.1440 as RBA holds OCR steady at 3.6%, as expected FXStreet

Continue Reading

-

China’s Li says tariff consequences increasingly evident

BEIJING, Dec 9 (Reuters) – China’s Premier Li Qiang said on Tuesday the “mutually destructive consequences of tariffs have become increasingly evident” over 2025, in remarks at a “1+10 Dialogue” including the heads of the IMF, World Trade Organization and World Bank.

Without naming U.S. President Donald Trump, China’s second-highest ranking official told the meeting in Beijing that greater effort was needed to reform global economic governance due to the trade barriers.

Sign up here.

China’s trade surplus topped $1 trillion for the first time in November, trade data showed on Monday, which economists say is linked to Trump’s tariffs diverting shipments from the world’s second-largest economy to other markets, putting pressure on manufacturing sectors in those economies.“Since the beginning of the year, the threat of tariffs has loomed over the global economy,” Li told the meeting, which also includes senior officials from the OECD and International Labour Organization.

Li also said artificial intelligence is becoming central to trade, highlighting models such as China’s DeepSeek as drivers of the global transformation of traditional industries and as catalysts for growth in new sectors, including smart robots and wearable devices.

Reporting by Joe Cash; Editing by Sam Holmes

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

Continue Reading

-

Japan’s offshore wind sector: Down but not out

In August 2025, a consortium led by Mitsubishi Corporation announced its withdrawal from three offshore wind projects in Japan. The decision raised concerns about the viability of the country’s offshore wind sector, long viewed as a cornerstone of its renewable energy expansion. The stated cause — surging construction costs linked to inflation — is not unique to Mitsubishi; developers across Europe and elsewhere face the same challenge.

Yet it would be premature to conclude that offshore wind development in Japan has reached a dead end. Although developers are grappling with structural barriers, the government has begun reassessing its auction framework and implementing reforms that could make the next bidding round more attractive.

Japan’s wind energy plans

Japan’s 7th Strategic Energy Plan aims to increase the share of renewable energy in power generation from approximately 20% to 40%–50% by fiscal year (FY) 2040. Within this target, wind power is expected to rise from approximately 1% to between 4% and 8%, with offshore wind positioned as the centerpiece of this expansion. Japan added more offshore wind capacity in 2024 than ever before, albeit from a modest base, reaching 253.4 megawatts (MW) of operational offshore wind capacity. Meanwhile, onshore wind capacity stood at 5,330MW at the end of that year.

In 2020, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) published its “Vision for Offshore Wind Power Industry,” aiming for 10 gigawatts (GW) of total wind capacity by 2030. METI began drafting a second version of the plan in March 2025. Meanwhile, the Japan Wind Power Association has outlined a longer-term vision to build 140GW of wind capacity by 2050, comprising 40GW onshore, 40GW fixed offshore, and 60GW floating offshore capacity.

Recent political developments in Japan are likely to affect the trajectory of its energy policy. The newly elected prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, has been a strong advocate for nuclear energy and has highlighted the risks of relying on foreign suppliers for conventional solar panels. While she has shown less resistance to offshore wind, she has emphasized a goal of achieving 100% energy self-sufficiency. Under her administration, Japan’s decarbonization strategy is expected to place greater emphasis on energy security and industrial competitiveness.

Mitsubishi’s winning bids and subsequent withdrawal

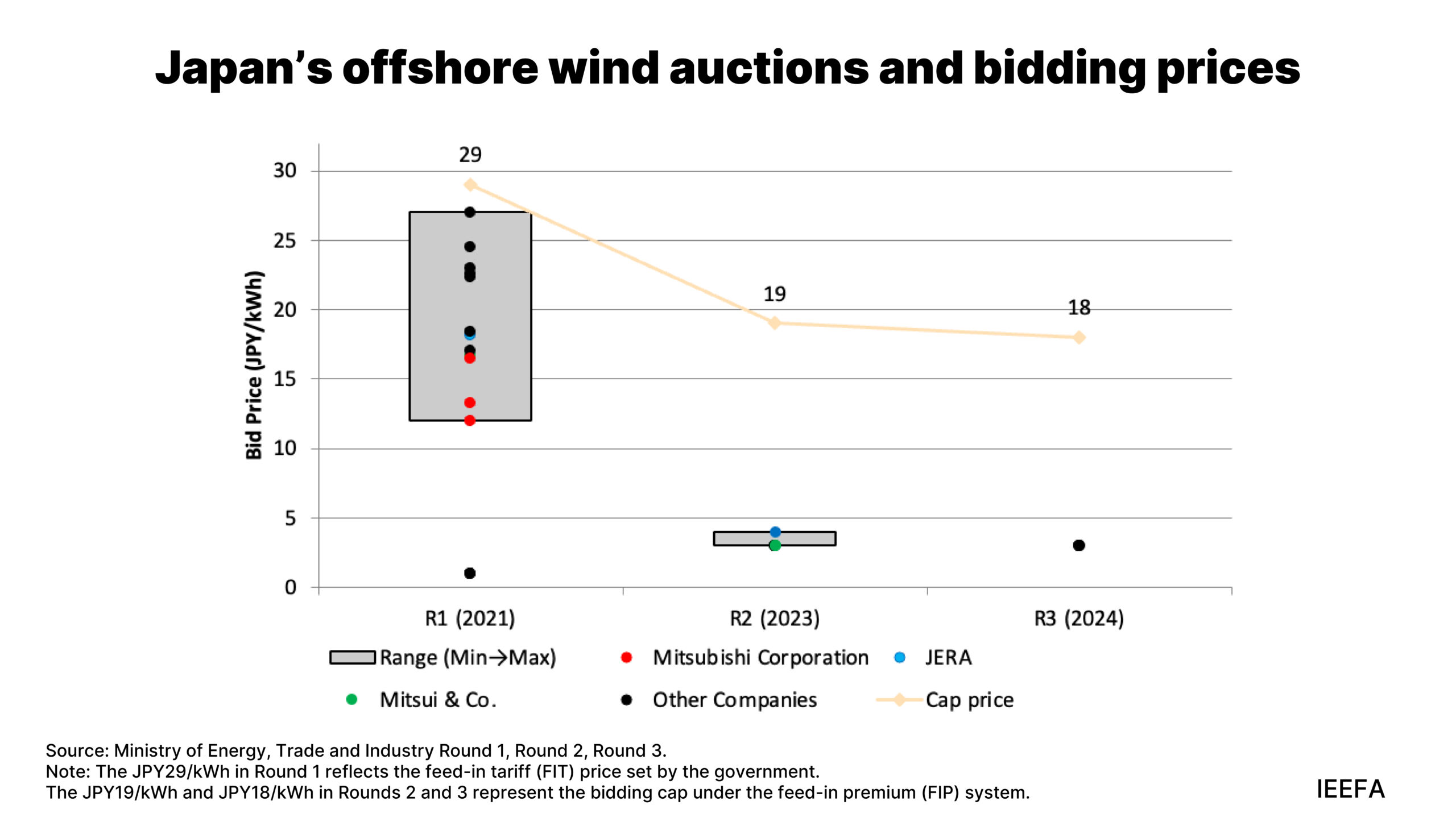

Mitsubishi’s withdrawal from three offshore wind projects reflects both company-specific missteps and broader structural issues in Japan’s offshore wind market. In 2021, Japan held its first offshore wind auction for three projects with a combined capacity of 1.7GW. Under the feed-in tariff (FIT) scheme, companies would compete for projects by submitting low-cost bids but would ultimately win contracts set at higher, predetermined fixed rates. The process enabled price discovery while also enhancing financial security for project backers.

In the first round, a Mitsubishi-led consortium won all three projects with a bidding price between JPY11.99 and JPY16.49 per kilowatt-hour (kWh), or USD10.85 cents per kilowatt-hour (¢/kWh) and USD14.8¢/kWh. This was far lower than the JPY29/kWh (USD26.1¢/kWh) ceiling price set by the government and the JPY17–JPY24.5/kWh (USD15.3¢/kWh to USD22.0¢/kWh) range from other bidders. Mitsubishi’s bid range was closer to that seen in more mature, established European markets than in an inaugural auction. These bids appeared competitive but left little buffer for cost inflation.

In the years following the auction, Mitsubishi’s project costs more than doubled, with total investment ballooning above JPY1 trillion (USD6.4 billion). The company announced a JPY52.2 billion (USD0.3 billion) impairment on the three offshore wind projects, exacerbated by inflation, global supply chain disruptions, yen depreciation, and rising turbine costs. In Japan, average construction costs for offshore wind projects were 20% higher in FY2024 than in FY2020, compared to an 8.5% increase in the cost of consumer goods. This is broadly consistent with trends in Europe, where capital costs increased by 18% between 2019 and 2024.

Factors constraining Japan’s offshore wind sector

Across the wind energy industry, all major segments — turbines, cables, foundations, and substations — have been affected by inflation, driven by rising raw material and energy prices, as well as persistently high shipping rates. Global equipment and materials prices have surged since 2022, particularly for turbines, subsea cables, monopiles, and substations, driving engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) costs higher. For example, wind turbines have typically accounted for 30% of the capital expenditure (capex) required for Japanese fixed offshore wind projects in FY2025. However, turbine costs reportedly increased by 10%–15% between 2021 and 2023.

Monopile foundation costs, which typically account for approximately 8% of capex for Japanese wind projects, have been almost entirely sourced from Europe. European steel prices, the main cost driver for turbines and monopiles, surged by around 200% between late 2020 and mid-2022. Although global steel prices have since fallen to near-2019 levels, the decline in turbine costs has been slow. Shipping and installation expenses have also increased due to post-COVID supply chain bottlenecks. Transporting monopiles from Europe can cost around JPY300 million (USD1.9 million), underscoring Japan’s reliance on imports — a challenge that extends across its offshore wind supply chain.

By 2040, Japan aims to achieve over 65% local content across its entire offshore wind supply chain. Currently, however, the country lacks a domestic supplier for offshore wind turbines. Toshiba plans to establish a nacelle assembly line at its Yokohama plant in partnership with General Electric (GE), but production has not started yet. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Hitachi also previously pursued wind turbine manufacturing, but were unable to establish a sustained, large-scale domestic supply foundation. As a result, Japan’s offshore wind projects continue to rely heavily on imported turbines. Nevertheless, there are opportunities to substantially increase the proportion of wind farm costs sourced domestically, even in the absence of a full turbine manufacturing base.

Importantly, turbines now account for less than 30% of total offshore wind capex in Japan. The remaining 70% consists of balance-of-plant components — foundations, towers, cables, transmission systems, installation vessels, port upgrades, and operations — many of which align closely with Japan’s existing industrial strengths. The country already hosts globally competitive firms in specialty steel production, heavy fabrication, electrical equipment, shipbuilding, and marine logistics.

Therefore, what is lacking is not industrial capability but the effective mobilization of that capability. Irregular auction schedules and an unpredictable long-term project pipeline have prevented domestic industries from scaling or repositioning to meet offshore wind demand, reinforcing reliance on imported equipment, even when domestic alternatives exist.

Japan already forges the specialty steels used in offshore wind foundations and turbine towers. Despite this, developers continue to import these components from Europe. Hitachi, Toshiba, and Mitsubishi manufacture a large proportion of the transmission system components needed for both offshore and onshore portions of wind farm interconnections. The country also has a world-class shipbuilding industry, capable of fabricating vessels of all sizes and specialties, which is a critical requirement for offshore wind farms. These ships need crews, port facilities, and maintenance services, reinforcing the potential for domestic economic spillovers if offshore wind supply chains are localized.

Along with higher component costs, the weak yen and rising interest rates have increased import and capital financing costs. Since 2021, the yen has significantly weakened. On an annual-average basis, the exchange rate increased from 109.78 JPY/USD in 2021 to 151.50 in 2024 — a 38% depreciation. These currency fluctuations have inflated dollar-denominated equipment prices and amplified project financing costs. Moreover, Japanese short-term policy rates are at their highest level since 2008, with future hikes anticipated in 2026. Although lower financing costs, compared to those in the United States (US) and Europe, have been cited as an advantage for Japanese wind projects, recent increases in debt costs have eroded that benefit.

Additionally, regulatory and permitting barriers further increase overall project expenses. In Japan, it takes 6–8 years from the start of permitting to the commercial operation date for fixed-bottom offshore wind projects. By contrast, the European Union (EU) caps the permit-granting process at two years for offshore projects. Japan’s lengthy baseline lead time increases exposure to component price volatility, rising financing costs, and delays, making projects more costly and risk-prone by global standards.

Like Mitsubishi, other bidders in the third offshore wind auction would likely have faced the same inflationary challenges. However, this case highlights more than just the risks of aggressive bidding. To realize its offshore wind ambitions, Japan should address its high domestic costs and unfavorable auction rules that incentivize low bids.

Auction price comparisons: Japan vs. international benchmarks

Japan’s first offshore wind auction in 2021 highlighted the stark disparity between domestic and international prices. Bidding prices in Japan’s first round were between JPY11.99/kWh and JPY24.5/kWh. This was two or three times higher than international benchmarks, such as the United Kingdom’s (UK) 2021 Round 4 bid at GBP37.35 per megawatt-hour (MWhGBP37.35 per megawatt-hour (MWh) (around JPY7–8/kWh) or Germany and Taiwan’s Round 3.2 with zero-premium bids. A zero-premium bid refers to an auction scheme in which developers bid with a premium — defined in the support scheme as a subsidy — set at zero, and proceed with the project solely based on revenues linked to wholesale electricity market prices.

At first glance, Japan’s results appear uncompetitive. However, the higher ceiling prices set by the government reflected the country’s unique conditions rather than an intentional distortion. Japanese developers must pay for grid connections and seabed reinforcement, which are often covered by governments in Europe. Long permitting timelines and coordination with fisheries extend project risks, raising financing costs. The absence of inflation indexation forces bidders to price in uncertainty, while dependence on imported turbines exposes them to exchange-rate and shipping risks.

Japan’s high auction prices are the product of systemic design and cost burdens, not technological inefficiency. Recognizing these differences is essential to understanding why the country’s offshore wind auctions are more expensive compared to its global peers. It also underscores why recent government reforms aimed at correcting low-price competition and easing structural burdens will be critical for unlocking Japan’s true offshore wind potential.

Evolution of Japan’s offshore wind policy framework

The Japanese government has started amending its offshore wind policy framework in response to the issues revealed in Round 1 bidding. In January 2025, it revised core auction guidelines to address excessively low-price bidding and project delays. The new rules allow developers to reflect up to 40% of cost inflation in the electricity price between the auction and the start of construction. For projects allocated from Round 4 onwards, bid bonds for operational delays increase from JPY13,000 per kilowatt (kW) to JPY24,000/kW — double that of projects assigned from Rounds 1 to 3 — and are structured as phased penalties to discourage speculative bidding and ensure project completion. Scoring criteria have also shifted from a price-only evaluation to factor in feasibility and local contributions.

Moreover, in November 2025, the government announced seven measures to enhance the bankability and completion prospects of offshore wind projects. These include a provision that zero-premium projects in Rounds 2 and 3 will be allowed to participate in the Long-Term Decarbonization Power Source Auction, securing 20 years of capacity revenue. The price-adjustment mechanism will continue to reflect only future inflation. Developers may also revise key equipment, including turbines, in cases of supplier withdrawal or significant cost escalation. Additional measures include more flexible base port rules, “renewal in principle” for occupation permit extensions, improved valuation of renewable attributes, and integrated grid, port, and financial support for low-carbon investments.

Strengthening domestic supply chains

METI also aims to reinforce domestic supply chains through initiatives, such as the July 2025 memorandum of understanding with Vestas and Nippon Steel, to localize turbine component production. The government has also pledged to reauction the sites abandoned by Mitsubishi under these new rules.

The initial bidding rounds highlighted the cost risks associated with weak domestic supply chains. Japan could address both exchange rate impacts on wind farm costs and the need to localize the offshore wind supply chain by domestically sourcing steel, foundation and tower fabrication, and other key components in the balance of systems and services. Beyond the turbines themselves, these inputs and services account for 60% to 70% of total project expenses. Japan’s advanced steel production, fabrication, integration, project management, and logistics systems are well-suited to meet offshore wind demands. The country’s shipbuilding sector could also benefit from producing specialized vessels needed for offshore wind farm installation and maintenance. Additionally, Japan is home to leading global suppliers of key components for cabling and transmission system elements, especially high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission components. As the offshore wind auction market matures and scales, the advantages of onshoring or localizing a greater share of wind turbine manufacturing and assembly become increasingly clear.

Expanding the scope for offshore wind projects

In June 2025, the Japanese parliament passed a law allowing the installation of offshore wind farms in the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This is a significant development as it effectively expands the geographical scope for future auctions beyond Japan’s territorial waters, opening vast new areas for large-scale offshore wind development. With one of the world’s sixth-largest EEZs, Japan could now access deeper and windier sites with higher capacity factors and lower seasonal variability, giving new momentum to its long-term offshore wind ambitions.

The government is considering reauctioning the three sites in Akita and Chiba that were awarded in Round 1, following Mitsubishi’s withdrawal from the projects.

Simultaneously, attention is turning to the upcoming Round 4 auction. Two new offshore areas near Matsumae and Hiyama in Hokkaido have been designated as promotion zones, and a public tender is expected for these sites. However, the government postponed the launch of Round 4, initially scheduled for 14 October 2025. The delay is intended to provide time to assess the reasons behind developers’ withdrawal from the three Round 1 sites and to establish conditions to ensure offshore wind investments can reach completion. Therefore, the postponement is not a setback, but a constructive step toward refining the auction framework and fostering a more sustainable market environment.

Optimistic outlook for the sector

Despite these headwinds, other renewable energy developers remain optimistic about the long-term outlook for the sector. At a recent industry event, Masato Yamada, Senior Vice President at JERA Nex bp Japan Ltd., remarked, “There’s a perception that offshore wind power is dead, but the initiative hasn’t even truly begun.” Regarding the company’s Round 2 project off the coast of Akita, he further noted that withdrawing would result in greater losses, making continued development the rational choice. His comments underscore that, despite recent setbacks, developers still have strong incentives to move projects forward.

In fact, not all projects are stalled. Round 2 developments are progressing despite cost headwinds: Mitsui & Co. has selected its EPC contractor and plans to begin onshore construction in October 2025, Tohoku Electric is moving ahead with its 615MW Aomori project, and the Oga–Katagami–Akita consortium led by JERA Nex bp Japan has established a local headquarters with operations targeted for June 2028.

Round 3 developments are also progressing in line with planned construction and operation timelines. The consortium led by JERA is preparing fisheries impact assessments for its project off the southern coast of Aomori in the Sea of Japan, while Marubeni’s project off Yuza, Yamagata Prefecture, is moving forward on a similar schedule. Both projects target commercial operation in June 2030 and plan to use Siemens turbines. In June 2025, METI and Siemens Gamesa established a cooperation framework to discuss and promote the development of a wind turbine supply chain for the Japanese market and overseas expansion. Together, these efforts signal growing momentum toward strengthening Japan’s offshore wind industry through international collaboration and supply chain development.

These examples demonstrate that, alongside policy reform, tangible progress continues, highlighting that Japan’s offshore wind sector may be down — but is far from out.

Yet limitations remain

Despite the visible progress in Round 2 and the reforms introduced, Japan’s offshore wind developers still face structural headwinds. The latest measures — including the provision of 20 years of capacity revenues for zero-premium projects in Rounds 2 and 3, the allowance of turbine substitutions in the event of supplier withdrawal, and the shift toward “renewal in principle” for occupation permit extensions — are crucial mechanisms to reduce cancellation risks and improve financial visibility. However, these relief measures apply only to Rounds 2 and 3; from Round 4 onward, developers will return to a highly competitive environment.

At the same time, many of the fundamental bottlenecks identified by industry and in the Global Wind Energy Council’s (GWEC) recent white paper remain unresolved. These include:

(1) Insufficient inflation protection that does not compensate for past cost escalation, in stark contrast to the UK’s fully Consumer Price Index (CPI)-adjusted Contract for Difference (CfD)

(2) An underdeveloped corporate power purchase agreement (PPA) market and the absence of credit-guarantee schemes that constrain access to higher-priced offtake

(3) A lack of compensation mechanisms for curtailment risk

(4) The absence of a strategic offshore transmission plan and persistently high grid-connection costs

(5) Shortages of domestic ports and installation vessels, which continue to force developers to rely on costly foreign charters

(6) Regulatory inconsistencies — such as the implicit application of building standards — that prolong certification and permitting timelines, delaying revenue generation

Unless these structural issues are resolved, development costs will remain elevated, permitting will remain protracted, offtake options will stay limited, and incentives for meaningful domestic supply chain investment will continue to be weak. Addressing these challenges would establish a solid foundation for the long-term growth and stability of the offshore wind market and send a strong signal to domestic manufacturers to invest in localizing supply chains. Mitsubishi’s withdrawal showed that the difficulty was not only aggressive bidding but also weaknesses in the auction framework. With further institutional improvements, Japan can still realize its offshore wind potential. Accelerating climate policy and innovation in this sector will be essential to sustaining the country’s future competitiveness.

Continue Reading

-

Tata Electronics strikes Intel deal to build India’s chip supply chain

Signage for Tata Electronics Pvt Ltd. at the company’s factory in Hosur, Tamil Nadu, India, on Tuesday, Aug. 5, 2025.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Tata Electronics has lined up American chip designer Intel as a prospective customer as the division of Mumbai-based conglomerate Tata Group works to expand India’s domestic electronics and semiconductor supply chain.

Under a Memorandum of Understanding, the companies will explore the manufacturing and packaging of Intel products for local markets at Tata Electronics’ upcoming plants.

Intel and Tata also plan to assess ways to rapidly scale tailored artificial intelligence PC solutions for consumers and businesses in India.

In a press release on Monday, Tata said that the collaboration marks a pivotal step towards developing a resilient, India-based electronics and semiconductor supply chain.

“Together [with Intel], we will drive an expanded technology ecosystem and deliver leading semiconductors and systems solutions, positioning us well to capture the large and growing AI opportunity,” said N Chandrasekaran, Chairman of Tata Sons, the principal investment holding company of Tata companies.

Tata Electronics, established in 2020, has been investing billions to build India’s first pure-play foundry. The facility will manufacture semiconductor products for the AI, automotive, computing and data storage industries, according to Tata Electronics.

The firm is also building new facilities for assembly and testing.

India, despite being one of the world’s largest consumers of electronics, lacks chip design or fabrication capabilities.

However, the Indian government has been working to change that as part of efforts to reduce dependence on chip imports and capture a bigger share of the global electronics market, which is shifting away from China.

Under New Delhi’s “India Semiconductor Mission,” at least 10 semiconductor projects have been approved with a cumulative investment of over $18 billion.

Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan said the partnership with Intel was a “tremendous opportunity” to rapidly grow in one of the world’s fastest-growing computer markets, fueled by rising PC demand and rapid AI adoption across India.

Continue Reading

-

Five Key Takeaways from AMRO’s 2025 Annual Consultation Report on Singapore – ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office

Following the US tariff announcement on the so-called ‘Liberation Day’, Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong warned the nation to “brace ourselves for more shocks to come”. This has proved prescient. Global uncertainty has become the norm, and maintaining resilience while pressing ahead with reforms to promote long-term growth is essential for effective policymaking.

AMRO’s 2025 Annual Consultation Report on Singapore shows that Singapore has weathered external shocks well thus far. It also illustrates how strong policymaking, preparedness, and the ability to leverage structural advantages can reinforce resilience and support future competitiveness and growth potentials. The key takeaways from the report released today are:

1) Growth has been revised up significantly from October.

Singapore’s GDP is projected to grow by 4.1 percent in 2025 and 2.5 percent in 2026 – a sharp upward revision from our October projections of 2.6 and 1.7 respectively. The upgrade reflects solid performance in the first three quarters of 2025, supported by the global electronics upcycle, AI-related demand, and strong activity in financial services. However, the near-term outlook remains vulnerable to external risks, particularly US trade policy shifts and weaker global growth, even as the announced 100-percent tariff on pharmaceuticals has been delayed,

2) An adept mix of fiscal, monetary and trade policies will be needed to cushion near-term impacts from trade disruptions.

Fiscal support should be targeted to vulnerable businesses and households, while broad-based transfers should be phased out gradually. An easier monetary policy stance remains appropriate given the uncertain outlook and low inflation—projected at 0.9 in 2025 and 0.8 percent in 2026. However, sustained capital inflows, while contributing to lower domestic interest rates, could impose an upward pressure on the exchange rate and present challenges to monetary policy implementation. Meanwhile, strengthening international trade agreements and ensuring businesses fully utilize them will help unlock new export opportunities and diversify markets.

3) A whole-of-government approach is helping safeguard a stable and sustainable property market.

Close coordination across agencies has enabled the effective implementation of both demand- and supply- side measures to moderate property price increases. These include macroprudential and property market measures as well as efforts to increase housing supply. Maintaining tight macroprudential measures will help contain risks of property market overheating and rapid household debt accumulation amid lower interest rates induced by capital inflows.

4) Singapore must preserve its competitive edge amid aging and rising trade fragmentation.

Boosting workforce adaptability, fostering a dynamic business environment, accelerating the adoption of automation, and maintaining an agile regulatory framework will be key to maintain competitiveness. A multipronged approach, including fiscal and healthcare reforms, can help address structural challenges, particularly from demographic change.

5) Singapore is well placed to advance regional integration, lifting growth potential domestically and across ASEAN.

The Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone could serve as a blueprint for deeper intra-ASEAN integration, while ongoing regional initiatives on digital payments and financial market infrastructure connectivity are strengthening financial linkages. Singapore’s notable progress on climate adaptation and mitigation also positions it to play a leading role in regional climate governance and collaboration.

Conclusion

Singapore’s experience shows that resilience is not accidental. It is built through prudent policies, strategic foresight, and the agility to respond to emerging risks. As global uncertainties persist, the country’s continued commitment to sound macroeconomic management and structural reform will be vital to sustaining growth, enhancing competitiveness, and contributing to a more integrated and resilient ASEAN region.

Continue Reading

-

Warner Bros' lack of response fueled Paramount's hostile bid, filing says – Reuters

- Warner Bros’ lack of response fueled Paramount’s hostile bid, filing says Reuters

- Why has Paramount launched a hostile bid for Warner Bros Discovery? BBC

- Paramount Skydance launches hostile bid for WBD ‘to finish what we started,’ CEO Ellison tells CNBC CNBC

- Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Abu Dhabi are backing the Ellisons’ hostile bid for Warner Bros. Why? Business Insider

- Next shoe in Netflix-WBD saga drops as Paramount launches hostile bid that includes Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner Fortune

Continue Reading

-

Bitcoin’s November crash was no accident

By David Weidner

An always-on crypto hype machine lives to goose prices and then blame ‘macro’ when the selloff hits

As bitcoin cracked, liquidations mounted and short-term holders capitulated.

It’s the oldest game on Wall Street – the pump and dump. Only the tools have changed.

They came in by the tens of thousands: young, internet-native, mostly male, lured by the promise of lightning gains and financial freedom. For many, crypto wasn’t just an asset class – it was a storyline; a chance to get rich quickly and grab outsized returns before the mainstream figured out what was happening. That story was sold to them constantly through late-night livestreams, hyped Twitter threads, “moon or bust” Discord raids.

Now, after the crash, the crypto bros are showing signs of burnout – drained from margin calls, bag-holding and fading hope that the next “rocket tweet” will ever get them back to the high they were chasing.

The November wreck in bitcoin (BTCUSD) – from north of $120,000 to the low $80,000s – didn’t come out of nowhere. It was manufactured in plain sight by an always-on hype machine that lives to goose prices and then blame “macro” when gravity returns. Sure, crypto, including bitcoin, has rallied since falling below $85,000, but its “November to remember” crash wiped out dumb money. The subsequent rally only shows there’s dumber money out there.

We watched the script unfold in real time: chest-thumping year-end calls, retail pile-ins and leverage, a sharp downdraft, and then the postmortems telling the faithful to HODL [hold on for dear life] because the next big rally is imminent. Meanwhile, investors who bought the story are walking away. U.S. spot bitcoin ETFs bled roughly $3.5-$4 billion in November – their worst month since launch – as bitcoin erased its 2025 gains and slid into December still falling.

With crypto, you rarely need a smoking gun; leverage and narrative do the job.

This is how a walled-garden market works. Crypto’s most influential voices sell a future where bitcoin hedges U.S. dollar DXY debasement and soon sits beside gold (GC00) on central-bank balance sheets. Then they flood social media with price targets timed for maximum virality.

Arthur Hayes, the BitMEX co-founder, held the line on a $200,000 to $250,000 year-end bitcoin target even after November’s plunge – echoed by reposts and crypto media. Michael Saylor’s camp predicted $150,000 “by end of this year,” while VanEck reiterated an $180,000 “year-end” bitcoin target as late as August. This cheerleading sets sentiment, drives flows and helps build the runway for the next “sell the news.”

Then comes the unwind. With crypto, you rarely need a smoking gun – leverage and narrative do the job. As bitcoin cracked, liquidations mounted and short-term holders capitulated, while ETFs registered heavy outflows. The result was a trillion-dollar drawdown across digital assets and a price air-pocket down to the $80,000s. Even sympathetic analysts called it a classic “reset.” That’s a polite word for a market built on promotion, margin and the hope that the next post goes viral.

“Finfluencers” and coordinated campaigns can spark short-lived pops that fade once the insiders are out.

If this sounds like the oldest game on Wall Street – the pump and dump – that’s because it is. Only the tools have changed. “Finfluencers” and coordinated campaigns can spark short-lived pops that fade once the insiders are out. Crypto markets have billions in wash trading – fake volume that flatters momentum and dupes newcomers. Influencer calls deliver initial bumps that quickly evaporate.

Unsuspecting investors are told bitcoin isn’t just a trade – it’s insurance against the dollar – and, any day now, central banks will buy it. The facts say otherwise. The BIS, IMF and major central bankers keep drawing the same bright line: crypto is speculative, volatile and unsuitable as reserves; banks’ crypto exposure is tightly capped under global rules. Switzerland’s central bank publicly rebuffed bitcoin for reserves this year. Yes, you’ll find a headline-grabbing outlier – the Czech governor floated a small reserve allocation – but that remains a lonely view.

Read: For these big players, bitcoin investing is all about power

Crypto fatigue is setting in

If your due diligence begins and ends on social-media and chats, you’re playing a game where the other side writes the rules and the storyline.

Meanwhile, retail is exhausted. November brought multibillion-dollar redemptions, three straight weeks of ETF outflows and headlines about “crypto winter” all over again. Trading desks talk about “seller fatigue,” but that’s after the selling.

There’s a less glamorous explanation for bitcoin’s November plunge: It was due to content – a deliberate online campaign cycle. Early in the fall, the most widely followed social-media accounts planted calls for a bitcoin moonshot by December.

The memes did their work. Leverage piled in, and, when macro jitters and ETF outflows hit, the same voices reframed it as “healthy” before re-upping the end-of-year targets. Hayes’s bitcoin $250,000 post ricocheted across X; Saylor-adjacent channels packaged “this-year” price decks. In an unregulated attention economy, those posts are order flow. And when the tide turns, the exit is narrow.

The market structure amplifies it. Crypto still trades on venues where leverage is cheap, surveillance is lighter than with equities and market-making and marketing are indistinguishable. Crypto isn’t price risk; it’s narrative risk.

The crypto-hedge story – inflation, deficits, dollar debasement – sounds reasonable until investors find the correlations aren’t stable enough in the moments we need them most. November’s drop arrived alongside broader risk-off and funding stress – exactly when a “hedge” should help. Instead, bitcoin traded like a high-beta risk asset. Even crypto-friendly explainers acknowledged the slide reflected investors “ditching risk” and short-term capitulation.

Investors aren’t dumb. They’re human. Many of them are young and inexperienced. They listen to confident voices. But if your due diligence begins and ends on social media and chats, you’re playing a game where the other side writes the rules and the storyline. November was the reminder that, when an “asset” depends on engagement to work, the product is you.

Ultimately, investors should treat crypto’s influencer economy like any other funnel. When the call is for a year-end moonshot, ask who benefits if you buy that exposure today – and who’s already positioned to sell it back to you tomorrow. Recognize that the adoption stories (dollar hedge, central banks) remain mostly marketing copy, not monetary policy. If you still want exposure, size it like a lottery ticket, not a Treasury bill.

And when the next “healthy reset” arrives? Remember November.

David Weidner writes about markets, money and the stories behind them. His work has appeared in MarketWatch, The Wall Street Journal, McKinsey Quarterly, The Deal and American Banker.

Plus: This ‘safe’ cryptocurrency promises stability – but its claim is shaky

More: If you’re this type of investor, get out of the stock market now

-David Weidner

This content was created by MarketWatch, which is operated by Dow Jones & Co. MarketWatch is published independently from Dow Jones Newswires and The Wall Street Journal.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

12-08-25 2116ET

Copyright (c) 2025 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

Continue Reading

-

Significant Improvement in Quality of Life Reported in Updated HARMONi-6 Data for Ivonescimab at ESMO Asia

HONG KONG, Dec. 8, 2025 /PRNewswire/ — Akeso, Inc. (9926.HK) (“Akeso” or the “Company”) announced that at the 2025 ESMO Asia Congress, updated results from the pivotal Phase III HARMONi-6 study (AK112-306) were shared in an oral presentation by Professor Shun Lu from Shanghai Chest Hospital. The study evaluates ivonescimab (a first-in-class PD-1/VEGF bispecific antibody) combined with chemotherapy versus tislelizumab combined with chemotherapy in first-line treatment for advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer (sq-NSCLC).

Beyond the previously reported efficacy data presented at the ESMO 2025 Presidential Symposium and simultaneously published in The Lancet, this presentation further disclosed patient-reported quality of life outcomes based on the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire.

Both prolonging survival and improving quality of life are core indicators for evaluating cancer treatments. The results published at 2025 ESMO Asia demonstrate that, compared to the tislelizumab-based regimen, treatment with ivonescimab plus chemotherapy not only significantly prolongs progression-free survival (PFS) but also offers better tolerability, enables higher treatment adherence, and provides patients to maintain better overall health status and quality of life over a longer period. These findings highlight the comprehensive clinical value of the ivonescimab regimen in delivering both survival and quality-of-life benefits for patients.

- Quality of life (QoL) assessments from the HARMONi-6 study show that, compared with PD-1 inhibitor plus chemotherapy, ivonescimab plus chemotherapy not only significantly prolongs progression-free survival (PFS) but also helps patients maintain better overall health status. Time to deterioration in “Global Health Status/Quality of Life” was meaningfully delayed in the ivonescimab arm (HR = 0.94), indicating a trend toward reduced risk of QoL worsening versus the control group.

- The ivonescimab-based regimen met the primary PFS endpoint versus the tislelizumab-based regimen, delivering a decisive, strongly positive outcome with both statistical significance and clear clinical benefit. PFS was substantially prolonged with ivonescimab plus chemotherapy compared with tislelizumab plus chemotherapy.

- The hazard ratio for PFS between the ivonescimab and tislelizumab arms was 0.60 (P < 0.0001), corresponding to an absolute PFS improvement (ΔPFS) of 4.24 months (11.14 months vs. 6.90 months). This benefit was consistent across all PD-L1 expression subgroups.

The HARMONi-6 study enrolled 532 patients with well-balanced baseline characteristics. Among these patients, 92.3% had stage IV disease at enrollment. The squamous histology profile of the patients reflected real-world patterns, with approximately 63% of patients exhibiting the central squamous subtype (66.9% in the ivonescimab arm vs. 59.4% in the control arm). PD-L1 expression levels were also aligned with clinical expectations.

The results from the HARMONi-6 study further validate the breakthrough clinical value of the ivonescimab-plus-chemotherapy regimen compared to PD-1-plus chemotherapy regimen. The ivonescimab-plus chemotherapy regimen addresses a critical clinical gap when anti-angiogenic agents such as bevacizumab demonstrated severe safety considerations in the treatment of sq-NSCLC. Since ivonescimab’s initial approval in 2024, it has been evaluated in multiple clinical studies and used in real-world settings involving over 40,000 patients, where its transformative clinical benefits have been consistently demonstrated.

Across the immuno-oncology landscape, ivonescimab has shown clinical superiority to both PD-1 based treatments, which are currently the optimal standard of care for many cancers, and to also VEGF-targeted therapies in anti-angiogenesis based treatments.

In July 2025, based on the HARMONi-6 study results, the supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) for ivonescimab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line treatment for sq-NSCLC was accepted for review by the Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE) of China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA). Akeso’s partner, Summit Therapeutics, is currently carrying out a global multicenter Phase III HARMONi-3 study, evaluating ivonescimab plus chemotherapy versus pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC (both squamous and non-squamous subtypes).

Forward-Looking Statement of Akeso, Inc.

This announcement by Akeso, Inc. (9926.HK, “Akeso”) contains “forward-looking statements”. These statements reflect the current beliefs and expectations of Akeso’s management and are subject to significant risks and uncertainties. These statements are not intended to form the basis of any investment decision or any decision to purchase securities of Akeso. There can be no assurance that the drug candidate(s) indicated in this announcement or Akeso’s other pipeline candidates will obtain the required regulatory approvals or achieve commercial success. If underlying assumptions prove inaccurate or risks or uncertainties materialize, actual results may differ materially from those set forth in the forward-looking statements.

Risks and uncertainties include but are not limited to, general industry conditions and competition; general economic factors, including interest rate and currency exchange rate fluctuations; the impact of pharmaceutical industry regulation and health care legislation in P.R.China, the United States and internationally; global trends toward health care cost containment; technological advances, new products and patents attained by competitors; challenges inherent in new product development, including obtaining regulatory approval; Akeso’s ability to accurately predict future market conditions; manufacturing difficulties or delays; financial instability of international economies and sovereign risk; dependence on the effectiveness of the Akeso’s patents and other protections for innovative products; and the exposure to litigation, including patent litigation, and/or regulatory actions.

Akeso does not undertake any obligation to publicly revise these forward-looking statements to reflect events or circumstances after the date hereof, except as required by law.

About Akeso

Akeso (HKEX: 9926.HK) is a leading biopharmaceutical company committed to the research, development, manufacturing and commercialization of the world’s first or best-in-class innovative biological medicines. Founded in 2012, the company has created a unique integrated R&D innovation system with the comprehensive end-to-end drug development platform (ACE Platform) and bi-specific antibody drug development technology (Tetrabody) as the core, a GMP-compliant manufacturing system and a commercialization system with an advanced operation mode, and has gradually developed into a globally competitive biopharmaceutical company focused on innovative solutions. With fully integrated multi-functional platform, Akeso is internally working on a robust pipeline of over 50 innovative assets in the fields of cancer, autoimmune disease, inflammation, metabolic disease and other major diseases. Among them, 26 candidates have entered clinical trials (including 15 bispecific/multispecific antibodies and bispecific ADCs. Additionally, 7 new drugs are commercially available. Through efficient and breakthrough R&D innovation, Akeso always integrates superior global resources, develops the first-in-class and best-in-class new drugs, provides affordable therapeutic antibodies for patients worldwide, and continuously creates more commercial and social values to become a global leading biopharmaceutical enterprise.

SOURCE Akeso, Inc.

Continue Reading

-

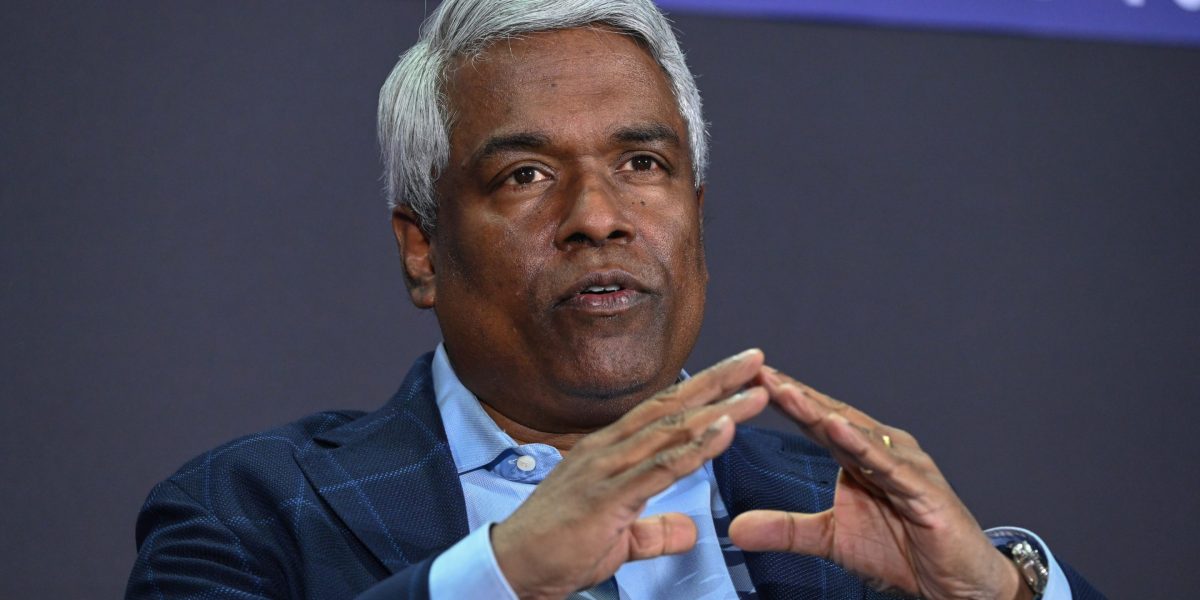

Google Cloud CEO lays out 3-part AI plan after identifying it as the ‘most problematic thing’

The immense electricity needs of AI computing was flagged early on as a bottleneck, prompting Alphabet’s Google Cloud to plan for how to source energy and how to use it, according to Google Cloud CEO Thomas Kurian.

Speaking at the Fortune Brainstorm AI event in San Francisco on Monday, he pointed out that the company—a key enabler in the AI infrastructure landscape—has been working on AI since well before large language models came along and took the long view.

“We also knew that the the most problematic thing that was going to happen was going to be energy, because energy and data centers were going to become a bottleneck alongside chips,” Kurian told Fortune’sAndrew Nusca. “So we designed our machines to be super efficient.”

The International Energy Agency has estimated that some AI-focused data centers consume as much electricity as 100,000 homes, and some of the largest facilities under construction could even use 20 times that amount.

At the same time, worldwide data center capacity will increase by 46% over the next two years, equivalent to a jump of almost 21,000 megawatts, according to real estate consultancy Knight Frank.

At the Brainstorm event, Kurian laid out Google Cloud’s three-pronged approach to ensuring that there will be enough energy to meet all that demand.

First, the company seeks to be as diversified as possible in the kinds of energy that power AI computation. While many people say any form of energy can be used, that’s actually not true, he said.

“If you’re running a cluster for training and you bring it up and you start running a training job, the spike that you have with that computation draws so much energy that you can’t handle that from some forms of energy production,” Kurian explained.

The second part of Google Cloud’s strategy is being as efficient as possible, including how it reuses energy within data centers, he added.

In fact, the company uses AI in its control systems to monitor thermodynamic exchanges necessary in harnessing the energy that has already been brought into data centers.

And third, Google Cloud is working on “some new fundamental technologies to actually create energy in new forms,” Kurian said without elaborating further.

Earlier on Monday, utility company NextEra Energy and Google Cloud said they are expanding their partnership and will develop new U.S. data center campuses that will include with new power plants as well.

Tech leaders have warned that energy supply is critical to AI development alongside innovations in chips and improved language models.

The ability to build data centers is another potential chokepoint as well. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang recently pointed out China’s advantage on that front compared to the U.S.

“If you want to build a data center here in the United States, from breaking ground to standing up an AI supercomputer is probably about three years,” he said at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in late November. “They can build a hospital in a weekend.”

Continue Reading