- Boeing gets Dubai Airshow boost as Emirates orders 65 more 777X Reuters

- Emirates bets big on Boeing with $38 billion order at Dubai Airshow CNBC

- Emirates Orders 65 More Boeing 777X Airplanes The Boeing Company

- Emirates Signs Deal for 130 Additional GE Aerospace Engines to Power its Growing Boeing 777-9 fleet Yahoo Finance

- Dubai Airshow 2025: Historic eVTOL flight and $52bn Boeing Deal Air Cargo Week

Category: 3. Business

-

Boeing gets Dubai Airshow boost as Emirates orders 65 more 777X – Reuters

-

Peter Thiel's fund offloaded Nvidia stake in third quarter, filing shows – Reuters

- Peter Thiel’s fund offloaded Nvidia stake in third quarter, filing shows Reuters

- After Japan’s second-richest man, this American billionaire sells his entire Nvidia stake worth $100 mill Times of India

- Peter Thiel Cuts Stake In PayPal Mafia Company Tesla. Musk Issues This Warning. Investor’s Business Daily

- Peter Thiel follows SoftBank in quitting Nvidia position as talk of AI bubble intensifies MarketWatch

- Peter Thiel’s hedge fund dumps Nvidia stake, cuts back Tesla position CNBC

Continue Reading

-

Global Landscape of Energy Transition Finance 2025 – Climate Policy Initiative

- Global Landscape of Energy Transition Finance 2025 Climate Policy Initiative

- Solar PV Investment Surged To A Record $554 Billion In 2024 TaiyangNews

- Global renewable energy investment hit USD 807 billion in 2024 St Vincent Times

- Africa accounts for just 2.3% as renewable investment hits $2.4trn The Guardian Nigeria News

Continue Reading

-

NASA, Industry Weave Data Fabric with Artificial Intelligence

One of the biggest goals for companies in the field of artificial intelligence is developing “agentic” or autonomous systems. These metaphorical agents can perform tasks without a guiding human hand. This parallels the goals of the emerging urban air mobility industry, which hopes to bring autonomous flying vehicles to cities around the world. One company got a head start on doing both with some help from NASA.

Autonomy Association International Inc. (AAI) is a public benefit corporation based in Mountain View, California, near NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley. In 2022, AAI signed a Space Act Agreement with Ames to support the agency’s Data and Reasoning Fabric project, which aimed to support the transportation of people and cargo to areas previously unserved or underserved by aviation, and to provide reliable, accurate, and current data for aeronautic decision-making.

“Inspiration to lean into data fabric to solve certain complexities came from our NASA partnership,” said AAI cofounder and the project’s industry principal investigator Greg Deeds. “Working on this project was a great experience. Working with NASA engineers and leaders gave us experience that we’ll carry forward in all of our products.”

Similar to how clothing fabric is made of intertwined threads, a data fabric comprises intertwined data sources. While a data fabric built by a tech company may include data from a few different cloud service providers, NASA’s Data and Reasoning Fabric can also use information provided by local governments and other service providers. By viewing airspace as a large data fabric, an autonomous vehicle can take in data and requests from the cities and towns it flies over and prioritize responses between them.

Working with Ken Freeman, principal investigator of the project at Ames, AAI and NASA performed four testing adaptations of the data fabric technology in the air over Arizona. Using hardware and software developed by AAI, the flights tested advanced air mobility passenger flights and the use of a drone for rapid delivery of medical supplies from urban to rural areas and back, while sending new tasks to the aircraft in flight. A helicopter stood in for the drone and air taxi, flying over towns, universities, tribal lands, and the airspace around Phoenix Sky Harbor airport and obtaining data and programs given to it from different places.

“We’re focusing on the digital infrastructure building blocks of smart cities and regions of the future,” said Jennifer Deeds, chief operating officer and cofounder of AAI.

In the years since the original NASA project, the company has cultivated relationships and customers abroad, including companies in agriculture, real estate development, and industrial food production using its system to aggregate and manage data. Released in 2024, the company’s Digital Infrastructure Platform uses the same technology originally designed for the NASA flight test. A new, “agentic” version followed not long after, able to retrieve necessary AI programs with minimal interaction.

As AI unlocks innovation across American industries, NASA is equipping its commercial partners with the keys, using proven technology to generate breakthrough solutions.

Learn more: https://spinoff.nasa.gov/

Continue Reading

-

Characterization of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene family in linseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) and its potential implications in flowering time regulation | BMC Plant Biology

Identification and in silico characterization of LuTPS gene family

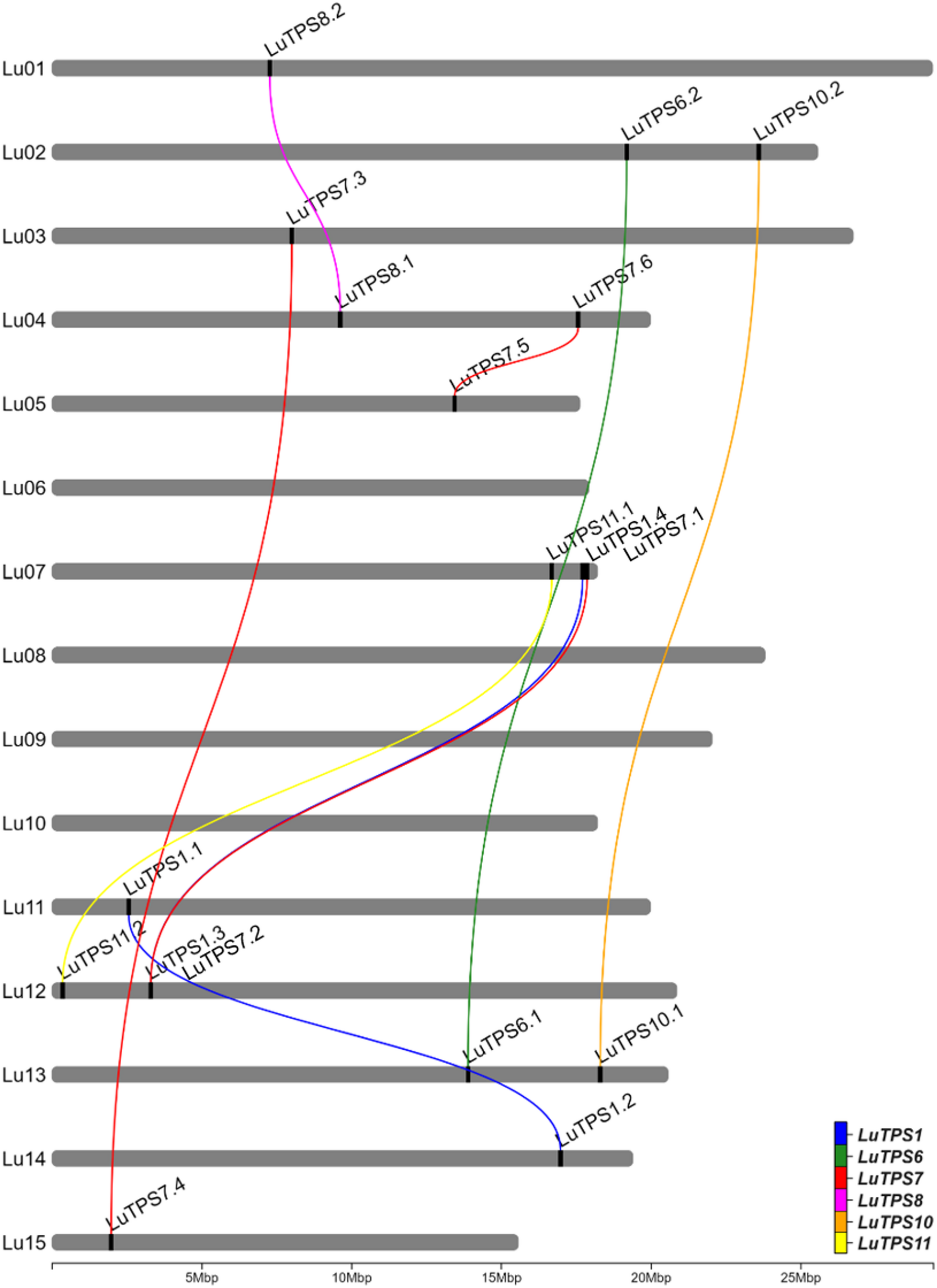

A total of 18 LuTPS genes were identified in silico, distributed across 11 of the 15 linseed chromosomes, excluding Lu06, Lu08, Lu09, and Lu10 (Fig. 1, Table 1). The LuTPS proteins ranged from 800 (LuTPS11.2) to 971 (LuTPS1.1) amino acids long. The predicted isoelectric point (pI) values varied from 5.50 (LuTPS7.6) to 7.05 (LuTPS1.1), with an average pI of 6.08. The predicted localization of the LuTPS proteins varied across different cellular compartments, with the majority localized in the chloroplast (7 proteins), followed by cytoplasm (5 proteins), nucleus (5 proteins), and one in vacuole. The highest number of phosphorylation sites was predicted for LuTPS1.3 and LuTPS1.4 (47 each), followed by LuTPS6.1 and LuTPS6.2 (38 each), and LuTPS1.1 and LuTPS1.2 (34 each), whereas the lowest number of phosphorylation sites was found in LuTPS7.1 and LuTPS7.2 (23 each) (Table 1). The LuTPS1 paralogs exhibited the most complex gene structures, with LuTPS1.1 containing 16 exons and LuTPS1.2, LuTPS1.3, and LuTPS1.4 each containing 17 exons. In contrast, other LuTPS genes displayed simpler structures, with exon numbers ranging from 2 (LuTPS10.2) to 4 (LuTPS11.2) (Figure S1).

Fig. 1 Chromosomal positions of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase genes in linseed and their paralogues. Lines connecting TPS genes indicate paralogous relation

Table 1 List of identified TPS genes in linseed and its in-silico characterization Phylogenetic analysis and nomenclature of linseed TPS

The LuTPS genes were named according to their closest Arabidopsis orthologs as identified in the pairwise distance matrix. In cases where multiple linseed genes showed similarity to the same Arabidopsis TPS, they were designated with numerical suffixes indicating their relative similarity to the Arabidopsis ortholog (Table 1). For phylogenetic analysis of LuTPS, the protein sequences of 18 LuTPS along with 11 AtTPS were aligned using t-coffee, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the ML method implemented in MEGA 11. The linseed TPS, along with Arabidopsis TPS, clustered into two distinct groups, Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (Fig. 2). The LuTPS1 paralogues (LuTPS1.1, LuTPS1.2, LuTPS1.3, LuTPS1.4) were found in Cluster 1, alongside the AtTPS1. Cluster 1 also included AtTPS2, AtTPS3, and AtTPS4. Cluster 2 was further divided into three subclusters, 2a, 2b, and 2c. Subcluster 2a contained LuTPS6.1 and LuTPS6.2, along with AtTPS6, as well as AtTPS5. Subcluster 2b was exclusively composed of LuTPS7 (LuTPS7.1, LuTPS7.2, LuTPS7.3, LuTPS7.4, LuTPS7.5, LuTPS7.6) together with AtTPS7. Subcluster 2c included paralogues of LuTPS8 (LuTPS8.1, LuTPS8.2), LuTPS10 (LuTPS10.1, LuTPS10.2), and LuTPS11 (LuTPS11.1, LuTPS11.2), which clustered alongside AtTPS8, AtTPS10, AtTPS11, and AtTPS9.

Fig. 2

Phylogenetic analysis of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) genes from linseed and Arabidopsis thaliana. The TPS genes are grouped into two major clusters, reflecting their evolutionary relationships

Expression analysis of LuTPS genes in vegetative and reproductive tissues

Gene expression profiles of the LuTPS genes in linseed were analyzed from the available transcriptome sequence data across four different tissues, bud at two developmental stages (bud1, bud2), flower, leaf, and stem, using RNA sequencing data from two early flowering-maturing accessions, IC0523807 and IC0525939. LuTPS6.1, LuTPS6.2, and LuTPS10.1 showed relatively higher expression in all the studied tissues including floral buds, flowers, leaf and stem in both the accessions. LuTPS10.1 showed conspicuously high expression in leaf in both the accessions (Fig. 3a, b). Most of the LuTPS genes except LuTPS1.3, LuTPS1.4, LuTPS7.5, and LuTPS7.6 were found expressed in one or more studied tissue types in both the accessions. A few genes showed high expression across all tissues in both the early flowering accessions which included LuTPS7.1, LuTPS7.2, LuTPS7.3, LuTPS7.4, LuTPS8.1, LuTPS8.2, LuTPS10.1, and LuTPS10.2. In contrast, LuTPS1.1, LuTPS1.2, LuTPS11.1, and LuTPS11.2 exhibited relatively higher expression in flower compared to other reproductive and vegetative tissues. Overall, the top most expressing LuTPS genes were LuTPS6.1, LuTPS6.2, and LuTPS10.1.

Fig. 3

Gene expression profiles of TPS genes in reproductive and vegetative tissues of early-flowering linseed genotypes IC0523807 and IC0525939 based on transcriptome data. Gene names are displayed on the right, with expression-based hierarchical clustering shown on the left. The color gradient from red to blue represents transcript abundance in TPM (Transcripts Per Million), ranging from high to low expression levels

To further pinpoint the potential linseed TPS genes involved in flowering regulation linseed, TPS gene expressions was compared to that of gene expression of important flowering regulators including FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) (Lus10013532), FRUITFULL (FUL) paralogs (Lus10011349, Lus10021140), SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1) (Lus10036543), Squamosa Promoter Binding Protein-Like 9 (SPL9) (Lus10007984) using the transcriptome of floral buds at two stages, flowers, leaves and stem of two early flowering linseed accessions IC0523807 and IC0525939 (Fig. 4). A positive correlation of FT was observed only with LuTPS1.1; while FUL (Lus10011349) showed positive correlation with LuTPS1.2, LuTPS6.1, LuTPS6.2, LuTPS7.2, LuTPS7.3, LuTPS7.4 and LuTPS8.2, indicating possible functional redundancy. Interestingly, LuTPS10.1 was the only gene which showed positive correlation with expression of the other FUL paralog (Lus10021140) and SOC1. There was no significant correlation of any TPS gene expression to that of SPL9, indicating no probable role of the latter in regulating TPS gene expression.

Fig. 4

Homology-based 3D structures of the LuTPS10.2 protein variant in linseed, showing the amino acid substitution at position 782: (a) GLY-782 in late-flowering genotypes and (b) VAL-782 in early-flowering genotypes. Intramolecular interactions of the LuTPS10.2 variants are illustrated for (c) GLY-782 and (d) VAL-782

Allelic variation in LuTPS genes in early and late linseed accessions

To investigate the allelic variations in LuTPS gene family, available whole genome sequencing data of two early flowering-maturing (IC0523807, IC0525939) and two late flowering-maturing (EC0115148, EC0718827) linseed germplasm accessions (Bio-project ID-PRJNA1207411; Table S1) was used and the reference-based SNP calling was performed. Trait-specific SNPs (those capable of distinguishing between early and late flowering-maturing accessions) were identified in two genes, LuTPS6.1 (3 SNPs: 2 SNPs in exons, 1 SNP in intron) (Table 2), and LuTPS10.2 (3 SNPs, all in exons) (Table 3). Both the exonic SNPs in LuTPS6.1 gene were synonymous in nature and therefore had no alteration in the protein sequence. Additionally, in the promoter sequence of the LuTPS6.1 gene, a total of 16 SNPs/indels were identified (Table 2). However, these variations in the promoter region did not exhibit any clear pattern associated with early or late flowering phenotypes. In LuTPS10.2, from the 3 SNPs, one SNP was non-synonymous at nucleotide position 2439 (‘G’ in late flowering-maturing group changed to ‘T’ in early flowering-maturing group) which resulted in an amino acid substitution, Glycine (a non-polar amino acid) to Valine (an aliphatic and hydrophobic amino acid) at position 782 in the resulting protein (Table 3, Figure S2). The other two SNPs were synonymous, causing no change in the protein sequence. Further, in the promoter sequence of LuTPS10.2, a total of 9 SNPs, and 18 indels were identified (Table 3). Of these, 10 SNPs exhibited phenotype-specific patterns, differing between early and late flowering-maturing accessions. Further, two insertions of 2 and 11 nucleotides (at position −1117 to −1116 and −627 to −617, respectively) and a single nucleotide deletion (at position−685) were observed in both early flowering accessions.

Table 2 SNP haplotype of LuTPS6.1 gene along with 2 kb promoter sequence in 2 early and 2 late flowering-maturing germplasm accessions of linseed. SNPs highlighted in bold font can differentiate between early and late flowering-maturing accessions Table 3 SNP haplotype of LuTPS10.2 gene along with 2 kb promoter sequence in 2 early and 2 late flowering-maturing germplasm accessions of linseed. SNPs highlighted in bold font can differentiate between early and late flowering-maturing accessions Effect of amino acid substitution on 3D structure of TPS protein

To evaluate the impact of the amino acid substitution on the LuTPS10.2 protein’s 3D structure, homology-based modeling was performed and the 3D structures of both the original protein (prior to amino acid substitution) and the modified protein (after substitution) were predicted and compared to evaluate any structural changes (Fig. 5a-d). Notably, the proteins from the early flowering-maturing group demonstrated an increase in intramolecular interactions, which typically enhances protein stability (Fig. 5c, d). The substitution of ‘G’ with ‘V’ in the early flowering-maturing group led to a significant reduction in potential energy, contributing to a stabilizing effect on the proteins within these accessions (Table 4).

Fig. 5

Correlation of expression of TPS genes and key flowering genes FT (Lus10013532), FUL paralogs (Lus10011349, Lus10021140), SOC1 (Lus10036543) and SPL9 (Lus10007984) in linseed. a Pairwise correlation between gene pairs. Color gradient of the circle from blue to red denotes positive to negative correlation. Size of the circle indicates the strength of p value. b, g Line plots depicting the normalized expression (Transcripts per Million) of TPS paralogs and flowering genes across tissues, floral bud 1, bud 2, flower, leaves, and stem in early-flowering linseed accessions IC0525939 and IC0523807. Expression data under NCBI, BioProject ID PRJNA773597 was used

Table 4 Potential energy of LuTPS10.2 protein before and after amino acid substitution in late and early flowering-maturing accessions Analysis of CREs in LuTPS genes and their enrichment

2 kb promoter sequences upstream of the start codon of 37,999 linseed genes were extracted from the linseed genome assembly. The position weight matrix data of 2,254 TF binding sites (TFBS) from the PlantPAN 3.0 database were used to predict the occurrence of CRE motifs within these promoter sequences. The CREs within the 2 kb promoter regions of 18 LuTPS genes were identified, and their enrichment was assessed by statistically comparing their frequency against the background frequency across the entire linseed genome (37,999 genes). A total of 32 CREs were identified as significantly enriched in the promoter sequences of LuTPS genes compared to the average genomic distribution at a threshold of q-value ≤ 0.1 (Table 5). Among the significantly enriched CREs, flowering and photoperiod related CREs included TF_motif_seq_0250, TF_motif_seq_0146, TF_motif_seq_0321, TFmatrixID_1221, TFmatrixID_0797, and TF_motif_seq_0481. It is intriguing to note that from the 32 enriched CREs, at least 15 were related to Dof-type domain-containing protein (Table 5). In addition, the promoter sequences of individual LuTPS genes were also analyzed for the presence of CREs using the PlantPAN4 database [62]. The analysis identified a total of 104 CREs, each present at least once in the promoter region of every LuTPS gene (Table S3). It is also important to highlight that six of the enriched CREs (TF_motif_seq_0250, TF_motif_seq_0315, TF_motif_seq_0344, TF_motif_seq_0238, TF_motif_seq_0321, and TF_motif_seq_0458) were consistently present in the promoter of all TPS genes in linseed (Table 5, Table S3).

Table 5 List of cis-regulatory elements enriched in LuTPS promoter sequences Genome scale syntenic network analysis of linseed and nine other plant genomes

To understand synteny of TPS genes in different crop plants, The genome scale syntenic network analysis of linseed and nine other plants representing cereals, oilseeds, pulses, and a model plant species (Arabidopsis, rice, barley, wheat, sesame, sunflower, soybean, greengram, and cowpea) was performed. A total of 68,930 conserved syntenic blocks (CSBs) were identified in the studied 10 plant species (Table 6). Among the comparisons, the highest number of CSBs involving linseed was found with soybean, (3,673 CSBs), followed by sunflower (2,159), cowpea (2,092), and sesame (2,018) while barley exhibited the fewest CSBs with linseed (588) (Fig. 6, Figure S3, Table 6). Notably, 179 of the 68,930 CSBs contained at least one LuTPS gene (Table 7). The highest number of LuTPS-containing CSBs was observed between linseed and soybean (43), followed by cowpea (25), sunflower (24), and sesame (22). Linseed itself had 15 intraspecific CSBs with gene counts per CSB ranging from 9 to 399 (Fig. 6, Table 7).

Table 6 Number of total CSBs identified among the 10 crops under study. The numbers in parentheses indicate the size (number of genes) of the smallest and largest CSBs. The numbers in curly braces denote the count of CSBs in the plus and minus orientations, respectively Fig. 6

Genome-wide synteny analysis of linseed with soybean (Glycine max) (a), sunflower (Helianthus annuus) (b), and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) (c). The genome wide conserved syntenic blocks (CSB) between the two species are depicted in grey shade, and the CSBs harbouring linseed TPS are shown with red lines

Table 7 Number of CSBs containing at least one LuTPS gene. The numbers in parentheses indicate the size (number of genes) of the smallest and largest CSBs. The numbers in curly braces denote the count of CSBs in the plus and minus orientations, respectively Syntenic gene collinearity networks (GCN) of linseed TPS

In order to identify LuTPS-specific syntenic block networks (SBN), the 179 CSBs (containing at least one LuTPS gene) were analyzed using Cytoscape software [48]. Accordingly, the 179 CSBs clustered into four distinct SBNs. The interaction of linseed TPS genes within these four SBNs was visualized as nodes (representing genes) and edges (representing syntenic relationships). Consequently, the linseed TPS genes formed four gene collinearity networks (GCN) (Fig. 7). Each node (gene) within the GCN represents the CSB in which this gene was located, while the edges highlight the syntenic relationships between them. The largest cluster, GCN Cluster-I (Fig. 7a), comprised of 35 genes, including 10 linseed TPS genes, LuTPS1.1, LuTPS1.2, LuTPS1.3, LuTPS1.4, LuTPS7.1, LuTPS7.2, LuTPS7.3, LuTPS7.4, LuTPS7.5, and LuTPS7.6. The remaining genes in this GCN were TPS genes from soybean, sunflower, cowpea, sesame, Arabidopsis, greengram, barley, and rice. The highest syntenic relationship for linseed TPS genes was observed with soybean and sunflower (6 genes each), followed by cowpea (4 genes), sesame (2 genes), Arabidopsis (2 genes), greengram (2 genes), rice (2 genes), and barley (1 gene). Within Cluster-I, subcluster-Ia consists of four linseed TPS genes (LuTPS1.1, LuTPS1.2, LuTPS1.3, and LuTPS1.4). Syntenic relationships were observed between LuTPS1.1 & LuTPS1.2, and between LuTPS1.3 & LuTPS1.4, though no direct connections were found between the two pairs. However, connections were observed with TPS genes from other plants, suggesting an ancient duplication event that led to the divergence of these gene pairs. Subcluster-Ia and subcluster-Ib were connected through a syntenic relationship between LuTPS1.2 and LuTPS7.5, facilitated by a TPS gene from greengram (XP_014493970.1). In subcluster-Ib, two linseed TPS genes, LuTPS7.5 and LuTPS7.6, displayed direct syntenic relationships. LuTPS7.5 also showed syntenic connections with TPS genes from cowpea and soybean. Subcluster-Ib was linked to Subcluster-Ic through syntenic relationships involving LuTPS7.5 and LuTPS7.6, both of which exhibited synteny with a TPS gene from sesame (XP_020550607.1). Subcluster-Ic comprised four linseed TPS genes (LuTPS7.1, LuTPS7.2, LuTPS7.3, and LuTPS7.4), all of which exhibited direct syntenic relationships with each other, indicating a high degree of conservation within this group. Cluster II was the smallest, with only 9 genes, including two linseed TPS genes, LuTPS6.1 and LuTPS6.2, which did not share direct syntenic interactions (Fig. 7b). Other genes in this cluster were from soybean, cowpea, greengram, sesame, and an Arabidopsis UDP-Glycosyltransferase/trehalose-phosphatase family protein (NP_001322467.1). LuTPS6.1 displayed direct syntenic connections with 7 genes, including the Arabidopsis gene, whereas LuTPS6.2 was connected with TPS genes from soybean, cowpea, greengram, and sesame. Interestingly, this cluster appears specific to dicot species, as no TPS genes from monocots (rice, barley, and wheat) were represented. Cluster III, containing 23 genes, featured four linseed TPS genes, LuTPS8.1, LuTPS8.2, LuTPS10.1, and LuTPS10.2 displaying direct syntenic relationships with one another (Fig. 7c). Other genes in the cluster are from soybean, cowpea, Arabidopsis, sunflower, sesame, greengram, and rice. Notably, wheat and barley TPS genes are absent from this cluster. LuTPS8.1 and LuTPS8.2 both interacted with 18 other TPS genes. The syntenic relationship with the sunflower TPS gene (XP_021976108.1) was specific to LuTPS8.1, while LuTPS8.2 uniquely showed interaction with the soybean TPS gene (XP_006578621.1). Additionally, both LuTPS10.1 and LuTPS10.2 demonstrate syntenic connections with 17 other TPS genes. Cluster IV consists of 17 genes, including two linseed TPS genes, LuTPS11.1 and LuTPS11.2, alongside TPS genes from other species (Fig. 7d). Notably, LuTPS11.1 and LuTPS11.2 exhibited a direct syntenic relationship with each other. Additionally, LuTPS11.1 displayed syntenic connections with all 16 other genes in the cluster, whereas LuTPS11.2 was syntenically linked to 14 genes, with the exceptions being the TPS genes from rice (XP_015610911.1) and soybean (XP_006593555.1). Notably, this cluster included TPS genes from all the ten plant species under study.

Fig. 7

Gene collinearity networks (GCNs) derived from conserved syntenic blocks (CSBs) containing TPS genes. Four GCN clusters (I–IV) are shown in panels (a–d). Each node represents a gene, annotated with the corresponding CSB, and edges indicate syntenic relationships between genes

To study if any of the genes in the linseed TPS specific CSBs also show any molecular interactions with TPS, we studied protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of TPS using the STRING database. The potentially interacting partners of each linseed TPS have been given in Table S4. There were a total of 27 unique interacting proteins identified for all 18 linseed TPS. Most linseed TPS paralogues shared the same interacting partners. Three of the interacting proteins, Lus10017984 (Uncharacterized protein), Lus10038739 (Hexosyltransferase), and Lus10041979 (Sucrose synthase) were part of the linseed TPS specific CSBs. Of which, Lus10017984 (Uncharacterized protein) showed PPI with LuTPS1.1, LuTPS1.2, LuTPS11.2. The other proteins, Lus10041979 (Sucrose synthase) showed PPI with 6 linseed TPS (LuTPS1.1, LuTPS1.2, LuTPS1.3, LuTPS1.4, LuTPS6.1, LuTPS6.2), whereas Lus10038739 (Hexosyltransferase) showed PPI specifically with LuTPS6.1, LuTPS6.2 (Table S4, Fig. 8a). From the 18 LuTPS, for the top ten expressing TPS genes (LuTPS6.1, LuTPS6.2, LuTPS10.1, LuTPS10.2, LuTPS7.1, LuTPS7.2, LuTPS7.3, LuTPS7.4, LuTPS8.1, LuTPS8.2) (Fig. 3), PPI network was drawn (Fig. 8a). For these 10 TPS, there were 20 unique interacting proteins, consisting mainly, trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatases, glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase, sucrose-phosphate synthase, hexosyltransferase etc. (Table S5). The co-expression analysis of these TPS genes with the interacting partners was done using the transcriptome data of two early flowering linseed accessions in floral buds at two stages, flowers, leaves and stem (Fig. 8b). Correlation analysis of LuTPS and their respective interacting partners showed significant positive correlation of Lus10038739 (Hexosyltransferase) with six TPS genes, LuTPS6.1, LuTPS6.2, LuTPS10.2, LuTPS7.1, LuTPS7.2, and LuTPS8.2 (Fig. 8c). Interestingly, Lus10041979 (Sucrose synthase) showed significant positive and negative correlation with LuTPS7.1 and LuTPS10.1, respectively. Five of the ten potential interacting partners of LuTPS6.1 and LuTPS6.2 showed positive correlation with them, which included hexosyltransferases (Lus10038739, Lus10003045), starch synthases (Lus1003324, Lus10008279), and glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase (Lus10023553). It is interesting to note that all linseed TPS, except LuTPS6.1 and LuTPS6.2 showed at least one of the interacting partners as trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase.

Fig. 8

LuTPS protein–protein interactions and co-expression with the potential interacting genes. a Protein–protein interaction network of linseed TPS as identified using string database. The central node with red color is TPS protein, other nodes with different colors indicate the interacting protein and edges indicate their interactions. b Co-expression of TPS genes and respective potential interacting partners in floral buds at two developmental stages, flower, leaf and stem in two biological replicates of early flowering linseed genotypes IC0523807 and IC0525939 based on transcriptome data. The gene expression value is in TPM. c Correlation of gene expression of linseed TPS genes and their potential interacting partners. Size of the circle indicates the strength of p value and color gradient of the circle from blue to red denotes positive to negative correlation

Continue Reading

-

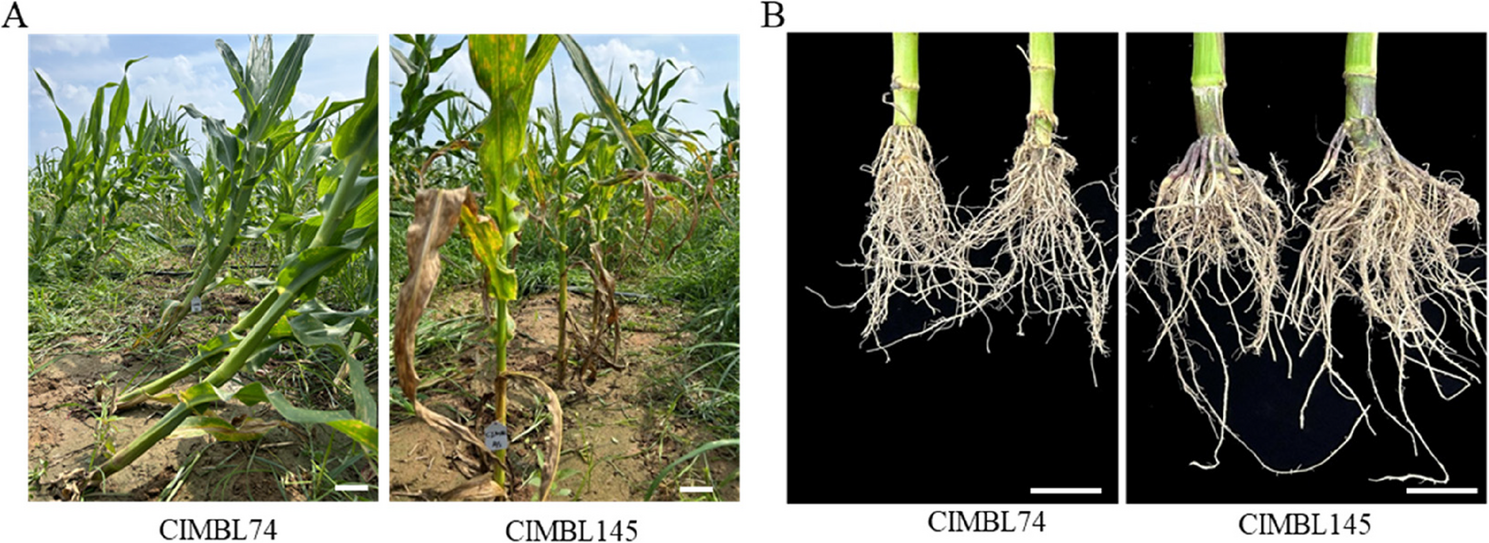

Hunting for the genetic loci underlying root lodging resistance by BSR-seq and QTL mapping in maize | BMC Plant Biology

Islam MS, Peng SB, Visperas RM, Ereful N, Bhuiya MSU, Julfiquar AW. Lodging-related morphological traits of hybrid rice in a tropical irrigated ecosystem. Field Crop Res. 2007;101(2):240–8.

Google Scholar

Ma DL, Xie RZ, Liu X, Niu XK, Hou P, Wang KR, Lu YL, Li SK. Lodging-Related stalk characteristics of maize varieties in China since the 1950s. Crop Sci. 2014;54(6):2805–14.

Google Scholar

Zhao B, Li K, Wang M, Liu Z, Yin P, Wang W, Li Z, Li X, Zhang L, Han Y, et al. Genetic basis of maize stalk strength decoded via linkage and association mapping. Plant J. 2024;117(5):1558–73.

Google Scholar

Pinthus MJ. Lodging in wheat, barley, and oats: the phenomenon, its causes, and preventive measures. Adv Agron. 1974;25:209–63.

Google Scholar

Xue J, Gao S, Hou LY, Li LL, Ming B, Xie RZ, Wang KR, Hou P, Li SK. Physiological influence of stalk rot on maize lodging after physiological maturity. Agronomy-Basel. 2021;11(11):2271.

Google Scholar

Shah AN, Tanveer M, Anjum SA, Iqbal J, Ahmad R. Lodging stress in cereal—effects and management: an overview. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2017;24(6):5222–37.

Google Scholar

Li Q, Fu CF, Liang CL, Ni XJ, Zhao XH, Chen M, Ou LJ. Crop lodging and the roles of Lignin, Cellulose, and hemicellulose in lodging resistance. Agronomy-Basel. 2022;12(8):1795.

Google Scholar

Rehman M, Luo D, Mubeen S, Pan J, Cao S, Saeed W, Chen P. Progress in agronomic crops lodging resistance and prevention: A review. J Agro Crop Sci. 2024;210(6):e12785.

Yang J, Li M, Yin Y, Liu Y, Gan X, Mu X, Li H, Li J, Li H, Zheng J, et al. Spatial accumulation of lignin monomers and cellulose underlying stalk strength in maize. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2024;214:108918.

Zhang Z, Zhang X, Lin Z, Wang J, Liu H, Zhou L, Zhong S, Li Y, Zhu C, Lai J, et al. A large transposon insertion in the stiff1 promoter increases stalk strength in maize. Plant Cell. 2020;32(1):152–65.

Google Scholar

Wang B, Yang M, Guo H, Wang J, Wang Z, Lu H, Qin G, Chen J. Genome-wide association study for stalk lodging resistance related traits in maize (Zea Mays L). BMC Genomics. 2024;25(1):19.

Sekhon RS, Joyner CN, Ackerman AJ, McMahan CS, Cook DD, Robertson DJ. Stalk bending strength is strongly associated with maize stalk lodging incidence across multiple environments. Field Crop Res. 2020;249:107737.

Google Scholar

Xu SH, Tang X, Zhang XM, Wang HM, Ji WD, Xu CW, Yang ZF, Li PC. Genome-wide association study identifies novel candidate loci or genes stalk in maize. Crop J. 2023;11(1):220–7.

Google Scholar

Hu H, Meng Y, Wang H, Liu H, Chen S. Identifying quantitative trait loci and determining closely related stalk traits for rind penetrometer resistance in a high-oil maize population. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124(8):1439–47.

Google Scholar

Zhang YL, Liang TH, Chen M, Zhang YC, Wang T, Lin HJ, Rong TZ, Zou CY, Liu P, Lee M, et al. Genetic dissection of stalk lodging-related traits using an IBM Syn10 DH population in maize across three environments (Zea Mays L). Mol Genet Genomics. 2019;294(5):1277–88.

Google Scholar

Liu XG, Hu XJ, Li K, Liu ZF, Wu YJ, Wang HW, Huang CL. Genetic mapping and genomic selection for maize stalk strength. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):196.

Sun Q, Liu X, Yang J, Liu W, Du Q, Wang H, Fu C, Li WX. MicroRNA528 affects lodging resistance of maize by regulating lignin biosynthesis under Nitrogen-Luxury conditions. Mol Plant. 2018;11(6):806–14.

Google Scholar

Zhao BB, Xu MY, Zhao YP, Li YY, Xu H, Li CY, Kong DX, Xie YR, Zheng ZG, Wang BB, et al. Overexpression of ZmSPL12 confers enhanced lodging resistance through transcriptional regulation of D1 in maize. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022;20(4):622–4.

Google Scholar

Chen S, Fan X, Song M, Yao S, Liu T, Ding W, Liu L, Zhang M, Zhan W, Yan L, et al. Cryptochrome 1b represses Gibberellin signaling to enhance lodging resistance in maize. Plant Physiol. 2024;194(2):902–17.

Google Scholar

Landi P, Sanguineti M, Darrah L, Giuliani M, Salvi S, Conti S, Tuberosa RJM. Detection of QTLs forvertical root pulling resistance in maize and overlap with QTLs for root traits in hydroponics. Maydica. 2002;47:233–43.

Landi P, Sanguineti M, Liu C, Li Y, Wang T, Giuliani S, Bellotti M, Salvi S, Tuberosa R. Root-ABA1 QTL affects root lodging, grain yield, and other agronomic traits in maize grown under well-watered and water-stressed conditions. J Exp Bot. 2006;58(2):319–26.

Google Scholar

Farkhari M, Krivanek A, Xu Y, Rong T, Naghavi MR, Samadi BY, Lu Y, Lübberstedt T. Root-lodging resistance in maize as an example for high‐throughput genetic mapping via single nucleotide polymorphism‐based selective genotyping. Plant Breeding. 2012;132(1):90–8.

Google Scholar

Zheng Z, Wang B, Zhuo C, Xie Y, Zhang X, Liu Y, Zhang G, Ding H, Zhao B, Tian M, et al. Local auxin biosynthesis regulates Brace root angle and lodging resistance in maize. New Phytol. 2023;238:142–54.

Google Scholar

Xie J, Guo G, Wang Y, Hu T, Wang L, Li J, Qiu D, Li Y, Wu Q, Lu P, et al. A rare single nucleotide variant in Pm5e confers powdery mildew resistance in common wheat. New Phytol. 2020;228(3):1011–26.

Google Scholar

Lin G, Chen H, Tian B, Sehgal SK, Singh L, Xie J, Rawat N, Juliana P, Singh N, Shrestha S, et al. Cloning of the broadly effective wheat leaf rust resistance gene Lr42 transferred from Aegilops Tauschii. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3044.

Wang Z, Niu Y, Xie Y, Huang C, Yung W-S, Li M-W, Wong F-L, Lam H-M. QTL mapping and BSR-seq revealed loci and candidate genes associated with the sporadic multifoliolate phenotype in soybean (Glycine max). Theor Appl Genet. 2024;137(12):262.

Shi L, Jiang C, He Q, Habekuß A, Ordon F, Luan H, Shen H, Liu J, Feng Z, Zhang J, et al. Bulked Segregant RNA-sequencing (BSR-seq) identified a novel rare allele of eIF4E effective against multiple isolates of BaYMV/BaMMV. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132(6):1777–88.

Google Scholar

Kim D, Landmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–U121.

Google Scholar

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–303.

Google Scholar

Mansfeld BN, Grumet R. QTLseqr: an R package for bulk Segregant analysis with Next-Generation sequencing. Plant Genome. 2018;11(2):180006.

Schenk JJ, Becklund LE, Carey SJ, Fabre PP. What is the modified CTAB protocol? Characterizing modifications to the CTAB DNA extraction protocol. Appl Plant Sci. 2023;11(3):e11517.

Google Scholar

Meng L, Li H, Zhang L, Wang J. QTL icimapping: integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J. 2015;3(3):269–83.

Google Scholar

Chen L, Luo J, Jin M, Yang N, Liu X, Peng Y, Li W, Phillips A, Cameron B, Bernal JS, et al. Genome sequencing reveals evidence of adaptive variation in the genus Zea. Nat Genet. 2022;54(11):1736–45.

Google Scholar

Langmead B, Salzberg SLJN. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9.

Google Scholar

Li H, Peng Z, Yang X, Wang W, Fu J, Wang J, Han Y, Chai Y, Guo T, Yang N. Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of oil biosynthesis in maize kernels. Nat Genet. 2013;45(1):43–50.

Google Scholar

Liu S, Yeh CT, Tang HM, Nettleton D, Schnable PS. Gene mapping via bulked Segregant RNA-Seq (BSR-Seq). PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36406.

Google Scholar

Mounier E, Pervent M, Ljung K, Gojon A, Nacry P. Auxin-mediated nitrate signalling by NRT1.1 participates in the adaptive response of Arabidopsis root architecture to the Spatial heterogeneity of nitrate availability. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;37(1):162–74.

Google Scholar

Cao H, Liu Z, Guo J, Jia Z, Shi Y, Kang K, Peng W, Wang Z, Chen L, Neuhaeuser B, et al. ZmNRT1.1B (ZmNPF6.6) determines nitrogen use efficiency via regulation of nitrate transport and signalling in maize. Plant Biotechnol J. 2024;22(2):316–29.

Google Scholar

Hostetler AN, Erndwein L, Reneau JW, Stager A, Tanner HG, Cook D, Sparks EE. Multiple Brace root phenotypes promote anchorage and limit root lodging in maize. Plant Cell Environ. 2022;45(5):1573–83.

Google Scholar

Imran M, Sun X, Hussain S, Rana MS, Saleem MH, Riaz M, Tang X, Khan I, Hu C. Molybdenum supply increases root system growth of winter wheat by enhancing nitric oxide accumulation and expression of NRT genes. Plant Soil. 2020;459(1–2):235–48.

Hu B, Wang W, Ou S, Tang J, Li H, Che R, Zhang Z, Chai X, Wang H, Wang YJNG. Variation in NRT1. 1B contributes to nitrate-use divergence between rice subspecies. Nat Genet. 2015;47(7):834–8.

Google Scholar

Fan X, Feng H, Tan Y, Xu Y, Miao Q, Xu GJJIPB. A putative 6-transmembrane nitrate transporter OsNRT1. 1b plays a key role in rice under low nitrogen. J Integr Plant Biol. 2016;58(6):590–9.

Google Scholar

Yin NW, Li B, Liu X, Liang Y, Lian JP, Xue YF, Qu CM, Lu K, Wei LJ, Wang R, et al. Two types of cinnamoyl-CoA reductase function divergently in accumulation of lignins, flavonoids and glucosinolates and enhance lodging resistance in brassica Napus. Crop J. 2022;10(3):647–60.

Google Scholar

Sakamoto S, Somssich M, Nakata MT, Unda F, Atsuzawa K, Kaneko Y, Wang T, Bagman AM, Gaudinier A, Yoshida K, et al. Complete substitution of a secondary cell wall with a primary cell wall in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants. 2018;4(10):777–83.

Google Scholar

Xiao C, Barnes WJ, Zamil MS, Yi H, Puri VM, Anderson CT. Activation tagging of arabidopsispolygalacturonase INVOLVED IN EXPANSION2promotes hypocotyl elongation, leaf expansion, stem lignification, mechanical stiffening, and lodging. Plant J. 2017;89(6):1159–73.

Google Scholar

Safran J, Tabi W, Ung V, Lemaire A, Habrylo O, Bouckaert J, Rouffle M, Voxeur A, Pongrac P, Bassard S, et al. Plant polygalacturonase structures specify enzyme dynamics and processivities to fine-tune cell wall pectins. Plant Cell. 2023;35(8):3073–91.

Google Scholar

Continue Reading

-

Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal cultivar-specific molecular responses of tea plants growing in Northern China | BMC Plant Biology

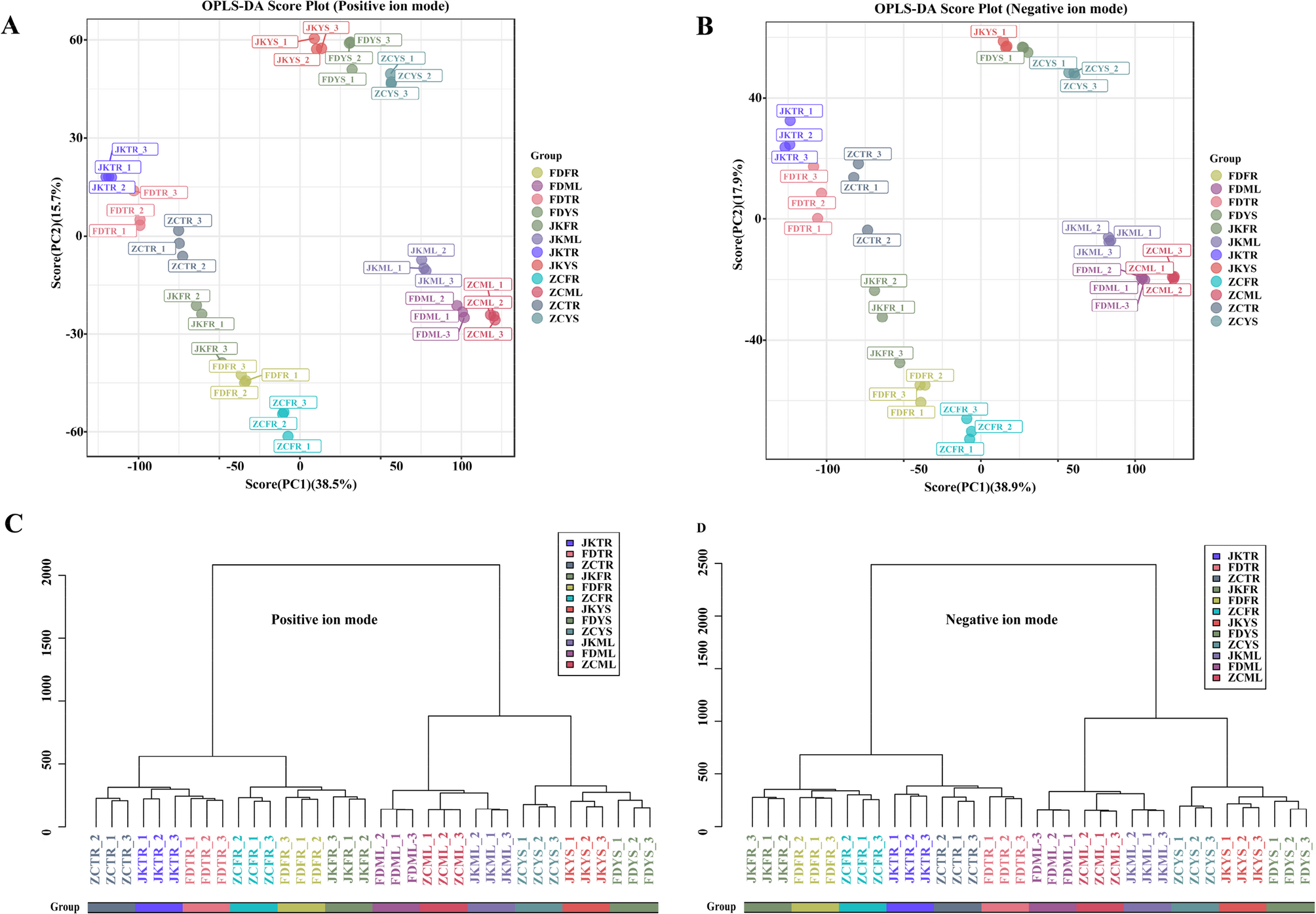

Comparative untargeted metabolomic profiling of three tea cultivars

To evaluate the metabolic adaptability of the tea cultivars ‘Zhongcha108’ (ZC), ‘Fuding Dabaicha’ (FD), and ‘Jiukeng’ (JK) under the environmental conditions of Ju’nan, a comprehensive untargeted metabolomics analysis was performed using UHPLC-MS. A total of 15,343 clean retention time-exact mass pairs in positive mode (accounting for 84.01%) and 168,869 in negative mode (83.83%) were detected in the samples. Those high-quality mass pairs were retained for downstream statistical analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed tight clustering of the QC samples (Fig. S2), indicating consistent instrument performance and reliable data acquisition. The orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) plots displayed clear metabolic differentiation among the four tissue types across the three tea cultivars under both ionization modes (Fig. 1A, B). This was further supported by hierarchical clustering (HCA) analysis, which demonstrated that each cultivar possessed a unique metabolite profile (Fig. 1C, D). In total, 854 metabolites were putatively identified across the three tea cultivars shown in Table S2. The detail information such as retention time (RT), mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) values, exact mass, formula and precursor type were included. These compounds encompassed a broad range of chemical categories, including 100 carboxylic acids and derivatives, 54 benzene-related compounds, 54 organooxygen compounds, 52 fatty acyls, 42 flavonoids, 42 prenol lipids, 23 steroids and their analogs, 19 organonitrogen compounds, as well as 15 azacyclics, 15 imidazopyrimidines, 15 phenolic compounds, 10 indole derivatives, among others. These findings highlighted the extensive biochemical diversity and cultivar-specific metabolic profiles of tea plants grown in this region.

Fig. 1 OPLS-DA score plots and hierarchical cluster for metabolic profiling analysis in positive (A) (C) and negative (B) (D) ion modes. The score of variation explained by each principal component is indicated on the axes. Each point corresponded to a plant sample, and different colors indicated the different cultivar tissues. ZC, ‘Zhongcha108’; FD, ‘Fuding Dabaicha’; JK, ‘Jiukeng’; YS, young shoots (one bud with two leaves); ML, mature leaves; TR, taproots, and FR, fibrous roots. Similarity assessment for clustering was based on the Euclidean distance coefficient and the average linkage method

Tissue-specific metabolic variations among three tea cultivars

To explore the metabolic differences contributed to cultivar variation, a pairwise comparative analysis was conducted among the ZC, FD, and JK tea cultivars across different tissue types. Significantly differential metabolites (SDMs) were identified based on the following criteria: VIP value ≥ 1 from the OPLS-DA model, p < 0.05, and a fold change (FC) ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67. Metabolites with significant increase or decrease abundance in one cultivar compared to the other two were defined as cultivar-specific differential metabolites (CSDMs).

In ZC, a total of 94 CSDMs were identified in young shoots, 121 in mature leaves, 34 in taproots, and 36 in fibrous roots (Fig. 2). For FD, the corresponding numbers were 48, 142, 28, and 19 (Fig. 2). In the case of JK, 43 CSDMs were identified in young shoots, 110 in mature leaves, 33 in taproots, and 24 in fibrous roots (Fig. 2). These findings underscored the metabolic diversity among tea cultivars and revealed that mature leaves tended to harbor the highest number of cultivar-specific metabolites across all genotypes examined.

Fig. 2

Upset Venn diagram of CSDMs in young shoots (YS) (A), mature leaves (ML) (B), tap roots (TR) (C) and fibrous roots (FR) (D) of ‘Zhongcha108’, ‘Fuding Dabaicha’, and ‘Jiukeng’ tea cultivars

To gain insights into the biological roles of the CSDMs, all identified CSDMs were matched against the KEGG database for pathway enrichment analysis. In the aerial tissues of the three tea cultivars, a substantial number of CSDMs were associated with the “flavonoid biosynthesis (ko00941)” and “phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940)” pathways. However, distinct pathway enrichments were also observed among cultivars. In ZC, the CSDMs from young shoots showed additional enrichment in “galactose metabolism (ko00052)” and “flavone and flavonol biosynthesis (ko00944)”. In contrast, young shoots of FD were particularly enriched in “arachidonic acid metabolism (ko00590)”, while its mature leaves exhibited specific enrichment in amino acid-related pathways (Fig. 3).

For belowground tissues, the metabolic patterns were more cultivar-dependent. In ZC, taproot-specific metabolites were significantly associated with pathways such as “limonene and pinene degradation (ko00903)”, “flavonoid biosynthesis (ko00941)”, and “phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis (ko00400)”. In its fibrous roots, metabolites were enriched in “citrate cycle (ko00020)”, “pyruvate metabolism (ko00620)”, and “ABC transporters (ko02010)” (Fig. 3A). In FD, CSDMs from tap roots were predominantly enriched in lipid-associated pathways, such as “linoleic acid metabolism (ko00591)”, “fatty acid biosynthesis (ko00061)”, “biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (ko01040)”, and “alpha-linolenic acid metabolism (ko00592)”. However, no significant pathway enrichment was observed for CSDMs in its fibrous roots (Fig. 3B). As for JK, the CSDMs in tap roots were only significantly enriched in “flavonoid biosynthesis (ko00941)”, whereas fibrous roots displayed enrichment in “arginine and proline metabolism (ko00330)” and “synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies (ko00072)” (Fig. 3C). Based on the enrichment analysis, flavonoids, sugars and sugar alcohols, as well as fatty acids were preliminarily identified as key metabolite classes for further analysis. These compounds were well known for their roles in antioxidant defense, osmotic regulation, and membrane remodeling, respectively. Thereby they might contribute to the cultivar-specific metabolic strategies that enable ZC, FD, and JK to cope with the environmental conditions of Ju’nan.

Fig. 3

The levels of CSDMs that significantly (p value ≤ 0.05) enriched in the KEGG pathways were visualized using heatmap in (A) ‘Zhongcha108’, (B) ‘Fuding Dabaicha’, and (C) ‘Jiukeng’ tea cultivars. Z-score normalization was applied to the data, and the red color indicated the higher level, the blue color indicated lower level. Vertical lines represented the metabolites involved in the certain pathway indicating in the legends

Transcriptomic profiling across different tissues of three tea cultivars

To investigate whether the observed metabolite variations among the three tea cultivars were in accordance with transcriptional changes, RNA sequencing was conducted on the samples. A total of 36 cDNA libraries were constructed. High-throughput sequencing yielded a total of approximately 234.40 Gb of high-quality clean data. All sequence data had been submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA accession: PRJNA1213152, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1213152). Each library generated over 40 million clean reads on average, with base quality scores (Q30) exceeding 89.24%. Alignment to the reference genome showed that 72.15% to 89.26% of the reads were successfully mapped, with 58.41% to 74.80% being uniquely aligned (Table S3). Pearson correlation analysis (Fig. 4) demonstrated strong consistency among the biological replicates, particularly in the root tissues (TR and FR), which exhibited higher correlation coefficients than the in aboveground tissues (YS and ML). This trend was consistent with the hierarchical clustering results obtained from the untargeted metabolomic data, indicating coordinated variation at both transcriptomic and metabolic levels across different cultivars and tissues.

Fig. 4

Correlation analysis of the average expression of 36 samples. The block on the heat map represents the correlation between two samples on the horizontal and vertical axes. The red and blue color indicated the positive and negative correlation, respectively

Differential expression profiling among three tea cultivars

To investigate transcriptomic variation among the tea cultivars under the environmental condition of Ju’nan, pairwise comparisons of gene expression were conducted across four tissue types, resulting in a total of 31,283 significantly differentially expressed genes (SDEGs). These comparisons included all possible combinations among ZC, FD, and JK in YS, ML, TR, and FR, including ZCYS_ vs. _FDYS, ZCYS_ vs. _JKYS, FDYS_ vs. _JKYS, and so on for the other tissues. To extract cultivar-specific transcriptional features, SDEGs were further filtered using stringent criteria: adjusted p value ≤ 0.01 and fold change (FC) ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67. Genes meeting these thresholds and showing consistent up- or down-regulation in one cultivar compared to the other two were defined as cultivar-specific differentially expressed genes (CSDEGs). Based on this refined selection, ZC cultivar exhibited 5,591 CSDEGs in young shoots, 5,929 in mature leaves, 1,443 in taproots, and 3,036 in fibrous roots (Fig. 5). For FD, 3,607, 4,577, 1,384, and 4,185 CSDEGs were detected in the respective tissues (Fig. 5). In the case of JK, the numbers were 4,558 in young shoots, 5,291 in mature leaves, 1,448 in taproots, and 3,576 in fibrous roots (Fig. 5). These results highlighted distinct tissue- and cultivar-dependent transcriptional regulation patterns.

Fig. 5

Venn diagram of CSDEGs in young shoots (YS) (A), mature leaves (ML) (B), tap roots (TR) (C) and fibrous roots (FR) (D) of ‘Zhongcha108’, ‘Fuding Dabaicha’, and ‘Jiukeng’ tea cultivars

Transcriptomic dissection of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis among three tea cultivars

Based on the KEGG annotation of cultivar-specific differential metabolites (CSDMs), variations in phenylpropanoid metabolism were observed in young shoots and mature leaves of the three tea cultivars. To further investigate the molecular basis underlying these metabolic differences, we performed a detailed analysis of gene expression involved in the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway.

A total of 133 genes encoding key enzymes in this pathway were differentially expressed in at least one tissue comparison (Fig. 6, Table S4). These included 5 phenylalanine ammonia-lyases (PAL), 1 cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 5 4-coumarate-CoA ligases (4CL), 2 caffeoylshikimate esterases (CSE), 21 cinnamoyl-CoA reductases (CCR), 42 shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferases (HCT), 1 C3′H monooxygenase, 2 caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferases (COMT), 2 ferulate 5-hydroxylases (F5H), 4 caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferases (CCoAOMT), 5 coniferyl aldehyde dehydrogenases (REF1), 7 cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenases (CAD), and 35 peroxidases.

As presented in the Fig. 6, expression of these genes varied greatly between tissues and cultivars. All five PAL genes (CSS0041448, CSS0010367, CSS0021474, CSS0001442, CSS0048281) exhibited higher expression in young shoots compared to mature leaves, with FD exhibiting the lowest expression levels in shoots. The sole C4H gene (CSS0011139) showed a consistent shoot-enriched pattern across all cultivars, with peak expression in FD. 4-Coumarate-CoA ligase catalyzes the third reaction in the general phenylpropanoid pathway, generating p-coumaroyl-CoA in an ATP-dependent process [32]. Among the 4CL genes, CSS0003013 and Camellia_sinensis_newGene_35622 displayed notably higher expression in ZC shoots, while FD leaves contained distinct 4CL with elevated expression level. The HCT family, which plays a key role in lignin synthesis, exhibited clear tissue-specific patterns. Most HCT genes were high expressed in shoots than in mature leaves, with 7, 12, and 12 members preferentially expressed in ZC, FD, and JK, respectively. Expression of the cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase gene C3′H was notably higher in shoots of FD and JK. For CCoAOMT, expression levels peaked in either the young shoots or mature leaves of JK, while the two COMT genes showed highest expression levels in ZC mature leaves and JK young shoots respectively. Of the two F5H genes, one was highly expressed in FD shoots, while the other showed relatively uniform expression in mature leaves across cultivars. CCR genes were predominantly expressed in mature leaves across cultivars, although six members in ZC were strongly expressed in young shoots, and other six expressed peaked in JK leaves. CAD genes, involved in the terminal step of monolignol biosynthesis, were generally expressed higher in mature leaves than young shoots, and most of these genes expressed highest in the mature leaves of ZC. In contrast, peroxidase genes, which mediate lignin polymerization [33], were more highly expressed in young shoots of all three cultivars. The FD young shoots had the least genes with highest expression levels. CSE genes showed elevated expression in both young shoots and mature leaves of FD and JK. REF1 was found to possess dehydrogenase activity toward both sinapaldehyde and coniferaldehyde, facilitating their oxidation into the corresponding carboxylic acids [34]. REF1 genes were most highly expressed in ZC, potentially contributing to its distinct lignin composition.

Altogether, the cultivar- and tissue-specific transcriptional regulation of phenylpropanoid pathway genes likely underpinned the observed variations in secondary metabolite accumulation, particularly those associated with lignin biosynthesis production.

Fig. 6

The pathways of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis enriched by KEGG analysis. The color of the rectangles indicated the expression of genes in the young shoots and mature leaves of ‘Zhongcha108’, ‘Fuding Dabaicha’, and ‘Jiukeng’ tea cultivars. Z-score normalization was applied to the data. Key genes were labeled in red color and the expression levels of these genes were highlighted by the red boxes

Expression profiles of flavonoid biosynthesis genes in three tea cultivars

To determine whether the expression patterns of flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes aligned with flavonoid accumulation in the aerial tissues of the three tea cultivars, genes involved in this metabolic pathway were examined. A total of 44 genes encoding key enzymes in flavonoid biosynthesis were identified from the transcriptomic dataset (Fig. 7). These included 4 chalcone synthase (CHS), 8 chalcone isomerase (CHI), 7 flavonol synthase (FLS), 1 flavone synthase II (FNS II), 4 phlorizin synthase (PGT1), 3 flavanone 7-O-glucoside 2’’-O-beta-L-rhamnosyltransferase (C12RT1), 1 naringenin 3-dioxygenase (F3H), 1 flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H), 9 dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), 2 anthocyanidin reductase (ANR), 2 anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), and 2 leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR) genes (Table S5).

A divergent expression landscape of these genes was observed across the three cultivars. As shown in Fig. 7, the expression levels of these genes varied significantly between young shoots and mature leaves in each cultivar. The following genes exhibited higher expression in either young shoots or mature leaves in ZC cultivar, including two CHS genes (CSS0004474, CSS0030597), four CHI genes (CSS0034202, CSS0028549, CSS0010290, CSS0035109), three PGT1 genes (CSS0004506, CSS0044620, CSS0011112), two C12RT1 genes (CSS0029726, CSS0019095), three FLS genes (Camellia_sinensis_newGene_18377, CSS0046529, CSS0033075), one ANS gene (CSS0010687), two LAR genes (CSS0027461, CSS0013982), and one F3′5′H gene (CSS0022212). For FD, three CHS genes (CSS0019002, CSS0007714, CSS0017197), two CHI genes (CSS0029305, CSS0050436), two FLS genes (CSS0007481, CSS0045924), one FNS II gene (CSS0007273), one F3H gene (CSS0019002), and three DFR genes (CSS0011557, CSS0016543, CSS0030876) showed higher expression in either young shoots or mature leaves. In JK, higher expression levels were observed for two CHI genes (CSS0025506, CSS0046350), two FLS genes (CSS0028720, CSS0007745), one C12RT1 gene (CSS0011196), six DFR genes (CSS0033346, CSS0024095, CSS0033342, CSS0009596, CSS0042695, CSS0003473), and one ANS gene (CSS0046216) in either young shoots or mature leaves. Certain gene subsets showed cultivar-specific high expression, suggesting differential regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis across cultivars and tissues.

Fig. 7

The pathways of flavonoid biosynthesis enriched by KEGG analysis. The color of the rectangles indicated the expression of genes in the young shoots and mature leaves of ‘Zhongcha108’, ‘Fuding Dabaicha’, and ‘Jiukeng’ tea cultivars. Z-score normalization was applied to the data. Key genes were labeled in red color and the expression levels of these genes were highlighted by the red boxes

Gene expression related to fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism in three tea cultivars

Given that the CSDMs in FD roots were mainly enriched in pathways associated with fatty acid accumulation, which differed from those of ZC and JK, the expression of genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism was examined to further explore the potential molecular mechanisms (Fig. 8, Table S6). In the alpha-linolenic acid metabolic pathway, 31 genes encoding related enzymes were identified, including 1 TAG lipase (TGL4), 13 phospholipase A1 (DAD1), 2 alpha-dioxygenase (DOX), 5 linoleate 9 S-lipoxygenase 6 isoform X2 (LOX2S), 3 alcohol dehydrogenase class-P (ADH1), 2 hydroperoxide dehydratase (AOS), 2 allene oxide cyclase (AOC), 2 chloroplastic oxoene reductase (CEQORH), 4 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase (OPR), 1 OPC-8:0 CoA ligase 1(OPLC1), 6 acyl-CoA oxidase (ACX), 2 acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 (ACCA1) and 2 jasmonate O-methyltransferase (JAMTF) genes. These genes were predominantly expressed at higher levels in the fibrous or tap roots of FD than that of JK and ZC (Fig. 8A). In the linoleic acid metabolism pathway, one PLA2G gene (secretory phospholipase A2) and two LOX1_5 genes (linoleate 9 S-lipoxygenase) showed higher expression levels in FD fibrous roots (Fig. 8B). Additionally, most genes associated with the general fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 8C) and unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 8D) exhibited relatively higher expression in FD root tissues compared to that of JK and ZC. The comparative analysis of fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism-related gene expression among the three tea cultivars revealed that FD exhibited distinct gene expression features in its root tissues. These findings highlighted fatty acid metabolism as a potential cultivar-specific adaptive trait in FD roots.

Fig. 8

The pathways of fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism enriched by KEGG analysisin the fibrous roots and taps roots of ‘Zhongcha108’, ‘Fuding Dabaicha’, and ‘Jiukeng’ tea cultivars. A Genes involved in the α-linolenic acid metabolic pathway; B Genes involved in the linoleic acid metabolism pathway; C Genes involved in the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway; D Genes involved in the unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway. The color of the rectangles indicated the expression of genes in the fibrous roots and taps roots of ‘Zhongcha108’, ‘Fuding Dabaicha’, and ‘Jiukeng’ tea cultivars. Z-score normalization was applied to the data. Key genes were labeled in red color

Analysis of differentially expressed transcription factors

Transcription factors (TFs) play crucial roles in regulating tea plant growth and development [35]. In this study, a total of 3,141 TFs were identified (Table S7) and categorized into 95 distinct families. The predominant TF families included MYB, bHLH, ERF, FAR1, C2H2, NAC and MYB-related, each containing over 100 members. To investigate the regulatory network behind the observed differences in phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis in the aerial parts of the three cultivars, Pearson correlation analyses were performed between the identified TFs and genes involved in these two pathways. A total of 6,952 TF–gene pairs exhibited a correlation coefficient greater than 0.8 with a significance level of p < 0.05, of which 3,850 were positively correlated (Table S8). The 20 most highly expressed TFs in each cultivar were selected for detailed correlation analysis (Fig. 9A). Heatmap analysis of expression patterns revealed that many of these TFs exhibited cultivar-specific patterns and were mainly upregulated in the shoots or leaves of FD (Fig. 9B). Specifically, TFs such as CSS0033564, CSS0041210, CSS0049449, CSS0029513, Camellia_sinensis_newGene_29682, CSS0048202 and CSS0048097 showed strong positive associations with structural genes including CSS0007745, CSS0039867, CSS0034202, CSS0007714, CSS0004474, CSS0021668, CSS0003013, CSS0041448, CSS0009063, CSS0025824, CSS0033075, CSS0026112, CSS0022212, CSS0046529, CSS0021474, CSS0030597 and CSS0028431. In contrast, the remaining 13 TFs were only positively associated with a smaller subset of structural genes, such as CSS0028496, CSS0007933 and CSS0002404. These TFs might function as key regulators orchestrating the differential expression of biosynthetic genes, thereby contributing to the observed variation in secondary metabolite profiles.

Further Pearson correlation analysis was also conducted between the TFs and genes implicated in fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism. A total of 188 TF–gene pairs showed correlation coefficients above 0.8 with p < 0.05, of which 148 pairs were positively correlated (Table S9). The 20 most abundantly expressed TFs per cultivar were again selected for this analysis (Fig. 9C). The heatmap results showed that these TFs displayed distinct expression profiles, with most presenting relatively low expression levels in the fibrous roots of FD (Fig. 9D). Only seven TF–gene combinations showed significant positive correlations. They were CSS0029616 vs. CSS0037941, CSS0031905 vs. CSS0037941, CSS0029851 vs. CSS0043714, CSS0031905 vs. CSS0046980, CSS0049449 vs. CSS0010933, CSS0045349 vs. Camellia_sinensis_newGene_6171, and CSS0049449 vs. Camellia_sinensis_newGene_17768. Together, these findings underscored the complexity and specificity of transcriptional regulation across different tissues and cultivars, and highlighted the importance of TFs in driving cultivar-dependent metabolic adaptations in tea plants.

Fig. 9

The regulation roles of the 20 TFs that top expressed in each cultivar. The Pearson correlation analysis of the TFs and genes involved in the phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis (A) and fatty acids biosynthesis and metabolism pathways (C). The expression levels of the TFs that top expressed in each cultivar of young shoots (YS) and mature leaves (ML) (B) and tap roots (TR) and fibrous roots (FR) (D)

qRT-PCR analysis

To validate the gene expression trends of the CSDEGs identified through RNA-seq, qRT-PCR was performed on 15 selected genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, and fatty acid metabolism pathways (Fig. S3). These genes were analyzed in young shoots and mature leaves or in tap roots and fibrous roots across the three tea cultivars. The qRT-PCR results demonstrated that the majority of the expression patterns were consistent with those observed in the RNA-seq data, confirming that the transcriptome results were reliable and suitable for subsequent analyses.

Continue Reading

-

Inpatient versus outpatient management of community-acquired acute skin and soft tissue infections. Clinical outcomes and factors associated with eligibility for early discharge | BMC Infectious Diseases

Bouza E, Burillo A, Muñoz P. How to manage skin and soft-tissue infections in the emergency department. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2023;36(2):81–8.

Google Scholar

Grossi AP, Ruggieri A, Vecchio A, Del Comandini A, Corio L, Calisti F, et al. Skin infections in Europe: a retrospective study of incidence, patient characteristics and practice patterns. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2022;60(3):106637.

Google Scholar

Peterson RA, Polgreen LA, Cavanaugh JE, Polgreen PM. Increasing Incidence, Cost, and seasonality in patients hospitalized for cellulitis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017 Feb 8;4(1)ofx008.

Kaye KS, Petty LA, Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD. Current Epidemiology, Etiology, and burden of acute skin infections in the united States. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(Supplement3):S193–9.

Google Scholar

Falcone M, Tiseo G. Skin and soft tissue infections in the elderly. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2023;36(2):102–8.

Google Scholar

Adly M, Woo TE, Traboulsi D, Klassen D, Hardin J. Understanding dermatologic concerns among persons experiencing homelessness: a scoping review and discussion for improved delivery of care. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25(6):616–26.

Google Scholar

Dellsperger S, Kramer S, Stoller M, Burger A, Geissbühler E, Amsler I, et al. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in skin and soft tissue infections: an algorithm-based prospective multicenter pilot trial. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac197.

Google Scholar

Mohammed SA, Roberts JA, Cotta MO, Rogers B, Pollard J, Assefa GM, et al. Safety and efficacy of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2024;64(2):107263.

Google Scholar

Tran TT, Gomez Villegas S, Aitken SL, Butler-Wu SM, Soriano A, Werth BJ et al. New perspectives on antimicrobial agents: Long-Acting lipoglycopeptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022 Jun 21;66(6)(6):e0261420.

Hazen A, Pizzicato L, Hom J, Johnson C, Viner KM. Association between discharges against medical advice and readmission in patients treated for drug injection-related skin and soft tissue infections. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;126:108465.

Google Scholar

Carratalà J, Rosón B, Fernández-Sabé N, Shaw E, del Rio O, Rivera A, et al. Factors associated with complications and mortality in adult patients hospitalized for infectious cellulitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22(3):151–7.

Google Scholar

Macía-Rodríguez C, Alende-Castro V, Vazquez-Ledo L, Novo-Veleiro I, González-Quintela A. Skin and soft-tissue infections: factors associated with mortality and re-admissions. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35(2):76–81.

Google Scholar

Talan D, Salhi B, Moran G, Mower W, Hsieh YH, Krishnadasan A, et al. Factors associated with the decision to hospitalize emergency department patients with a skin and soft tissue infection. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(1):89–97.

Google Scholar

Cieri B, Conway EL, Sellick JA, Mergenhagen KA. Identification of risk factors for failure in patients with skin and soft tissue infections. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(1):48–52.

Google Scholar

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Google Scholar

Jones AE, Trzeciak S, Kline JA. The sequential organ failure assessment score for predicting outcome in patients with severe sepsis and evidence of hypoperfusion at the time of emergency department presentation*. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1649–54.

Google Scholar

Rhee JY, Kwon KT, Ki HK, Shin SY, Jung DS, Chung DR, et al. Scoring systems for prediction of mortality in patients with intensive care unit-acquired sepsis. Shock. 2009;31(2):146–50.

Google Scholar

Guidance for industry acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: Developing drugs for treatment. 2013. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/guidances-drugs. Cited 2 Aug 2024.

Parra Caballero P, Pérez Esteban S, Patiño Ruiz ME, Castañeda Sanz S, García Vadillo JA. Actualización en fascitis necrotizante. Seminarios de la Fundación Española de Reumatología. 2012;13(2):41–8.

Google Scholar

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801.

Google Scholar

Barbier F, Timsit JF. Risk stratification for multidrug-resistant bacteria in patients with skin and soft tissue infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33(2):137–45.

Google Scholar

Keung EZ, Liu X, Nuzhad A, Adams C, Ashley SW, Askari R. Immunocompromised status in patients with necrotizing soft-tissue infection. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(5):419.

Google Scholar

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 13.0. 2023. http://www.eucast.org.

Stevens DL et al. Clin Infect Dis (2014; 59:147–59). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;60(9):1448–1448.

Abetz JW, Adams NG, Mitra B. Skin and soft tissue infection management failure in the emergency department observation unit: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2018;35(1):56–61.

Google Scholar

Blanes Hernández R, Rodríguez Pérez M, Fernández Navarro J, Salavert Lletí M. Current approach to skin and soft tissue infections. Thinking about continuity of care. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2023;36(Suppl1):37–45.

Google Scholar

Sartelli M, Guirao X, Hardcastle TC, Kluger Y, Boermeester MA, Raşa K, et al. 2018 WSES/SIS-E consensus conference: recommendations for the management of skin and soft-tissue infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13(1):58.

Google Scholar

Cyriac JM, James E. Switch over from intravenous to oral therapy: a concise overview. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2014;5(2):83–7.

Google Scholar

Bookstaver PB, Jenkins TC, Stenehjem E, Doron S, Brown J, Goldwater SH et al. Impact of outpatient vs inpatient ABSSSI treatment on outcomes: A retrospective observational analysis of medical charts across US emergency departments. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018 May 15;5(7)ofy109.

Claeys KC, Zasowski EJ, Lagnf AM, Sabagha N, Levine DP, Davis SL, et al. Development of a risk-scoring tool to determine appropriate level of care in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections in an acute healthcare setting. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7(4):495–507.

Google Scholar

Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Lannin NA, Clemson L, Cameron ID, Shepperd S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2022 Feb 24;2(2):CD000313.

Larney S, Peacock A, Mathers BM, Hickman M, Degenhardt L. A systematic review of injecting-related injury and disease among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;171:39–49.

Google Scholar

Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E, Drainoni M, Salhaney P, Edeza A, et al. Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in healthcare settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;198:80–6.

Google Scholar

Langham FJ, Curtis SJ, Tang MJ, Jomon B, Doyle JS, Vujovic O, et al. Acute injection-related infections requiring hospitalisation among people who inject drugs: clinical features, microbiology and management. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022;41(7):1543–53.

Google Scholar

Ti L, Ti L. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e53-9.

Google Scholar

Dunne MW, Talbot GH, Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Puttagunta S. Safety of dalbavancin in the treatment of skin and skin structure infections: a pooled analysis of randomized, comparative studies. Drug Saf. 2016;39(2):147–57.

Google Scholar

Vazquez Deida AA, Shihadeh KC, Preslaski CR, Young HL, Wyles DL, Jenkins TC. Use of a standardized Dalbavancin approach to facilitate earlier hospital discharge for vulnerable patients receiving prolonged inpatient antibiotic therapy. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 13;7(8):ofaa293.

Williams DN, Baker CA, Kind AC, Sannes MR. The history and evolution of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT). Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):307–12.

Google Scholar

Mirón-Rubio M, Parra Jordán JJ, González Ramallo VJ, Mujal Martínez A, Fernández Muixí J, Iglesias Gallego M, et al. Economic burden of skin and skin structure infections due to gram-positive bacteria in patients on hospital at home-based outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT). Rev Esp Quimioter. 2023;36(3):291–301.

Google Scholar

Chan M, Ooi CK, Wong J, Zhong L, Lye D. Role of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy in the treatment of community acquired skin and soft tissue infections in Singapore. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):474.

Google Scholar

Seaton RA, Sharp E, Bezlyak V, Weir CJ. Factors associated with outcome and duration of therapy in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT) patients with skin and soft-tissue infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38(3):243–8.

Google Scholar

Ong BS, Ngian VJJ, Yeong C, Keighley C.

Out Of Hospital And In Hospital Management Of Cellulitis Requiring Intravenous Therapy

. Int J Gen Med. 2019;12:447–53.

Huang V, Ruhe JJ, Lerner P, Fedorenko M. Risk factors for readmission in patients discharged with outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;19(1):50.

Google Scholar

Suzuki J, Johnson J, Montgomery M, Hayden M, Price C. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy among people who inject drugs: a review of the literature. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018 Aug 7;5(9):ofy194.

Buehrle DJ, Shields RK, Shah N, Shoff C, Sheridan K. Risk factors associated with outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy program failure among intravenous drug users. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017 May 23;4(3)ofx102.

Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, Stilwell MG, Fritsche TR. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and europe: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57(1):7–13.

Google Scholar

Ray GT, Suaya JA, Baxter R. Incidence, microbiology, and patient characteristics of skin and soft-tissue infections in a U.S. population: a retrospective population-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):252.

Google Scholar

Vella V, Galgani I, Polito L, Arora AK, Creech CB, David MZ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infection recurrence rates in outpatients: A retrospective database study at 3 US medical centers. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(5):e1045–53.

Google Scholar

Collazos J, de la Fuente B, García A, Gómez H, Menéndez C, Enríquez H, et al. Cellulitis in adult patients: a large, multicenter, observational, prospective study of 606 episodes and analysis of the factors related to the response to treatment. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204036.

Google Scholar

Leme RCP, Bispo PJM, Salles MJ. Community-genotype methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections in Latin America: a systematic review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2021;25(1):101539.

Google Scholar

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic.Acta Biomed. 2020; 91((1):):157–60.

Google Scholar

Continue Reading

-

CIArb Guidelines on AI: Key Soft Law Step in Arbitration – Natalia Chumak – Signature Litigation

- CIArb Guidelines on AI: Key Soft Law Step in Arbitration – Natalia Chumak Signature Litigation

- AI Arbitrators Will Destroy the Legal Profession (And That’s a Good Thing) JD Supra

- Stop worrying and learn to love AI Wisconsin Law Journal

- Commentary: AI and the Legal Profession at a Crossroads Caixin Global

- When AI’s the Arbiter, What Role Do Humans Play? Commercial Search

Continue Reading