Introduction

During pregnancy, adequate maternal nutrition is required to provide the increased nutritional requirements necessary for metabolic maintenance and fetal growth.1–4 In 2020, the Indonesian Ministry of Health documented 4627 maternal deaths, indicating an increase relative to 2019.5 The increase is attributed to the poor nutritional status of pregnant women.6,7 Insufficient multiple micronutrients during pregnancy can increase the risk of complications, including anemia, which affects about 40% of pregnant women globally and peaks at 49% in Southeast Asia.8,9 Multiple micronutrient insufficiency could negatively impact pregnancy outcomes, leading to fetal loss, low birth weight (LBW), preterm birth, preeclampsia, small for gestational age, postpartum depression, elevated risk of neural tube defects, and increased mortality risk.1,10,11 These have been related to immunological development and inadequate neurodevelopmental outcomes in children.12,13 Inadequate development during childhood can extend into adolescence and adulthood, resulting in poor academic performance, reduced income, and reduced human capital.12

To reduce the risk of various complications, the World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted the supplementation of pregnant women with multiple micronutrient supplementation (MMS) since 2016.14 The administration of MMS is recommended at a dosage of 180 tablets during the first six months of pregnancy.15 MMS is crucial for cellular metabolism, development, and maintaining normal physiological functioning in the human body. MMS is a micronutrient containing 15 vitamins and minerals that fulfill the body’s nutritional requirements. Micronutrient composition as specified by the United Nations International Multiple Micronutrient Antenatal Preparation – multiple micronutrient supplements (UNIMMAP – MMS) consists of vitamin A (800µg), vitamin D (5µg), vitamin E (10mg), vitamin C (70mg), vitamin B1 (1,4mg), vitamin B2 (1,4mg), vitamin B6 (1,6mg), vitamin B12 (2,6 µg), folic acid (400µg), iron (30mg), zinc (15mg), iodine (150µg), selenium (65µg), niacin 18mg, and copper (2mg).16–18 MMS plays essential roles for human reproduction from early pregnancy, facilitating gametogenesis, fertilization, embryogenesis, and the development of placental function, redox balance, and vascularization.2,19–21 MMS contributes a significant role in metabolic processes essential for cell proliferation, growth, and protein synthesis in early pregnancy, and it is crucial for the establishment of the fetal genome throughout gestation. Furthermore, MMS plays an essential role in organogenesis, the development of the fetal central nervous system, and early brain development. MMS is also critical in regulating hemoglobin metabolism and optimizing mitochondrial function during pregnancy.2,11 MMS was shown to reduce oxidative stress and improve mitochondrial function in a study conducted in Lombok, Indonesia.11 As a result, the risk of fetal loss or miscarriage was reduced by 10%, the risk of infant death was reduced by 18%, and the risk of LBW and premature birth was reduced by 14%. This was compared to using iron and folic acid (IFA) alone. Research conducted on a group of pregnant women who suffered from anemia revealed more substantial findings, including a reduction of the risk of fetal loss and neonatal mortality by 29%, a reduction of the risk of newborn death by 38%, and a reduction of the risk of low birth weight by 25%.2

In October 2024, the Indonesian government started to implement MMS to improve maternal nutrition nationwide, though it remains in the initial phases.22–24 However, the transition from IFA to MMS tablets in Indonesia might take several years and require critical resources, including human capital and financial investment.25 MMS may receive significant government attention and influence healthcare policies. Consequently, the government requires an economic evaluation study as a critical component in the decision-making process. Given Indonesia’s extensive territory, high population density, and the unmet nutritional requirements for pregnant women across its provinces, a comprehensive economic evaluation is necessary to facilitate informed decision-making by policymakers in allocating budgets, resources, and areas of coverage for maternal and child health programs.14,20,26–29 Numerous studies in Bangladesh,14,26–28 India,28,29 Pakistan,28,29 Tanzania,29 Mali,29 and Burkina Faso14 have shown that MMS was a cost-effective intervention compared to IFA in enhancing maternal and child health.14,26–29 This is the first study aimed at evaluating the cost-effectiveness of transitioning from IFA to MMS in Indonesia for enhancing maternal and child health, and its implications for priority setting in Indonesia based on their incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER).

Methods

Model Setting

We applied an open-access online modeling MMS cost-benefit tool developed by Nutrition International to estimate the cost-effectiveness of MMS compared to IFA in Indonesia at the national and sub-national levels (38 provinces). The MMS Tool incorporates a comprehensive set of background data into its foundational model, which has passed quality assurance by technical specialists to guarantee its accuracy, recentness, and relevance.30–32 MMS tools supply national and global policymakers with context-specific assessments that evaluate whether antenatal MMS is more cost-effective compared to IFA.31,32 A 10-year time horizon was applied to assess the cost-effectiveness value, given the substantial effectiveness of MMS in pregnant women. In these scenarios, we applied a coverage scenario at 44% on a national level (baseline), reflecting the current national adherence level of the IFA program in Indonesia, which stands at 44%,33 and a 100% coverage scenario, which is a hypothetical highest cost scenario. The assumption of 180 tablets consumed by each pregnant woman was utilized following WHO recommendations.3,9 The cost-effectiveness analysis of transitioning from IFA to MMS utilized a population of approximately 211,351 pregnant women, as indicated by the 2023 Indonesian Health Survey data.33 We analyzed the projected economic results of MMS compared to IFA at both the national and provincial levels. Additionally, we calculated the ICER by dividing the incremental costs by the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated using the standardized Cost-Benefit Tool developed by Nutrition International. This tool, which is publicly available on their website (accessible at: https://www.nutritionintl.org/learning-resources-home/mms-cost-benefit-tool/), generates ICER values automatically. Consequently, the results presented in the manuscript are the direct output from this validated tool. The economic value of DALYs averted, reflecting the total economic benefits of transitioning to MMS, is estimated using a monetised DALY approach based on the Value of Statistical Life (VSL). The VSL quantifies the monetary amount an individual is prepared to pay to prevent injury or illness, with variations observed across different countries. Various methods exist for calculating the VSL for a country. This MMS Tool utilizes country-level VSL estimates in LMICs from Viscusi and Masterman34 to derive the Value of a Statistical Life Year (VSLY) by dividing the VSL by the expected life expectancy at birth. The economic value of DALYs averted is calculated by taking the product of the estimated discounted DALYs averted in a particular scenario by the corresponding country’s VSLY. The calculation of the number of DALYs averted incorporates a discount rate of 3%.31,35

Cost Data

Costs are determined from the government’s perspective as the health system provider. The MMS cost-benefit modeling tool was designed according to fixed input cost parameters that covered three categories of costs: the cost of IFA, the cost of MMS, and the transition cost (Table 1). These costs are related to a transition from the IFA to the MMS program.30–32 All costs were converted to USD (2024). The cost of MMS was determined using the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Supply Catalogue.36 The highest price of MMS was set at USD 4 (IDR 61,600) for 180 tablets. The IFA cost was determined by the decree issued by the Indonesian Ministry of Health regarding drug claim prices. Price differences among regions in Indonesia arise from governmental authorities that adjust drug price claims according to logistics expenses, distribution factors, and geographical characteristics specific to each region.37 IFA supplementation requires 180 tablets to ensure 6 months of coverage, and it was priced at USD 3.31 (IDR 50,940).

|

Table 1 Breakdown of Costs (2024 USD/ IDR)

|

Transition costs include a range of expenditures that extend beyond direct interactions between patients and providers. These include logistical expenses and administrative costs at national and provincial levels, as well as investments in training, nutrition education activities, media promotion, and supervision mechanisms.38,39 In this scenario, the transition cost is set with an additional 13% markup rate applied to the medicine and supply price (ie MMS price) to cover logistics and administrative costs. The costs associated with program transition can constitute an essential component of the total costs.38,39 Table 1 presents the cost data at both the national and provincial levels.

Maternal Health Parameters

The effect measure is captured as DALY averted. DALY quantifies the overall disease burden by integrating years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs). One DALY lost signifies one year of healthy life lost; consequently, one DALY averted corresponds to the acquisition of one year of healthy life. Assessing the cost per DALY averted allows for the comparison of various health interventions and the evaluation of an intervention’s impact.26

The approach examines supplements based on their effectiveness in affecting various health outcomes. This study utilized an open-access online MMS cost-benefit modeling tool developed by Nutrition International,30–32 which was designed according to fixed input maternal health parameters as identified in two published reviews, Keats et al, 201940 and Smith et al, 2017.41 The following maternal health parameters examined in this study, including life expectancy at 73.93 years,33 maternal anemia at 27.7%,33 preterm birth at 11.1%,33 SGA (small for gestational age) at 23.8%, LBW at 6.1%,33 stillbirth at 10.5 per 1000 births,42 maternal mortality at 189 per 100,000 live births,42 neonatal mortality (male and female) at 3.3–3.5 per 1000 live births,42 and infant mortality at 7.8 per 1000 live births.42 These numbers are based on national data from the literature. Sources of health outcomes data include the Indonesian Health Survey 202333 (ie, for preterm birth, maternal anemia, LBW, and life expectancy), the Indonesian Health Profile 202342 (ie, for stillbirth, maternal mortality, neonatal mortality, and infant mortality), and research journals. To determine which provinces should be prioritized in conducting the IFA to MMS transition program, the data collection results were divided into 38 Indonesian provinces (see Table 2).

|

Table 2 Maternal Health Parameters

|

Priority Setting

We applied a cost-effectiveness league table to evaluate the prioritization of MMS implementation by comparing the ICER in each province to the national ICER. The cost-effectiveness league table can serve as a tool for resource and budget allocation. A cost-effectiveness league table is a commonly utilized tool for quantitatively ranking priorities based on efficacy, safety, and costs. Healthcare resources could be distributed according to the strategies listed in the league table, beginning with the province with the lowest ICERs and subsequently progressing to the provinces with higher ICERs in the ranking.43 In provincial-level scenarios, we adopted a baseline population coverage of 44%, consistent with the national level.

Sensitivity Analysis

We applied one-way deterministic sensitivity analyses to identify variables that might significantly affect results. We performed a one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of different input parameters on ICER. All parameters were adjusted by plus or minus 25% for DALYs lost and associated costs.44

Results

Maternal Health Outcomes

Implementing MMS in the 44% and 100% coverage scenarios resulted in 54.897 and 124,766 DALYs averted in Indonesia, respectively. MMS was estimated to have an impact on both scenario (44% and 100% coverage scenarios), resulting in 20,305 and 46,148 DALYs averted in stillbirth, 11,965 and 27,194 DALYs averted in neonatal mortality, 12,879 and 29,271 DALYs averted in preterm birth, 106 and 241 DALYs averted in LBW, 5656 and 12,855 DALYs averted in infant mortality and 9061 and 20,592 DALYs averted in SGA, respectively (Figure S1).

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

According to the perspective of the Indonesian government as the health system provider, the implementation of MMS yielded ICER values of USD 10 per DALY averted in the 44% coverage scenario. Implementing MMS under 100% coverage scenarios yielded an identical ICER value of USD 10 per DALY averted. Variations in coverage will affect the overall costs and benefits, both of which change linearly and proportionally. This is, provided that the ICER, defined as the cost per DALY averted, remains unchanged. The MMS implementation is considered highly cost-effective, as the ICERs remained significantly below the Indonesian one GDP per capita (USD 4870.13) in 2024.45

Priority Setting

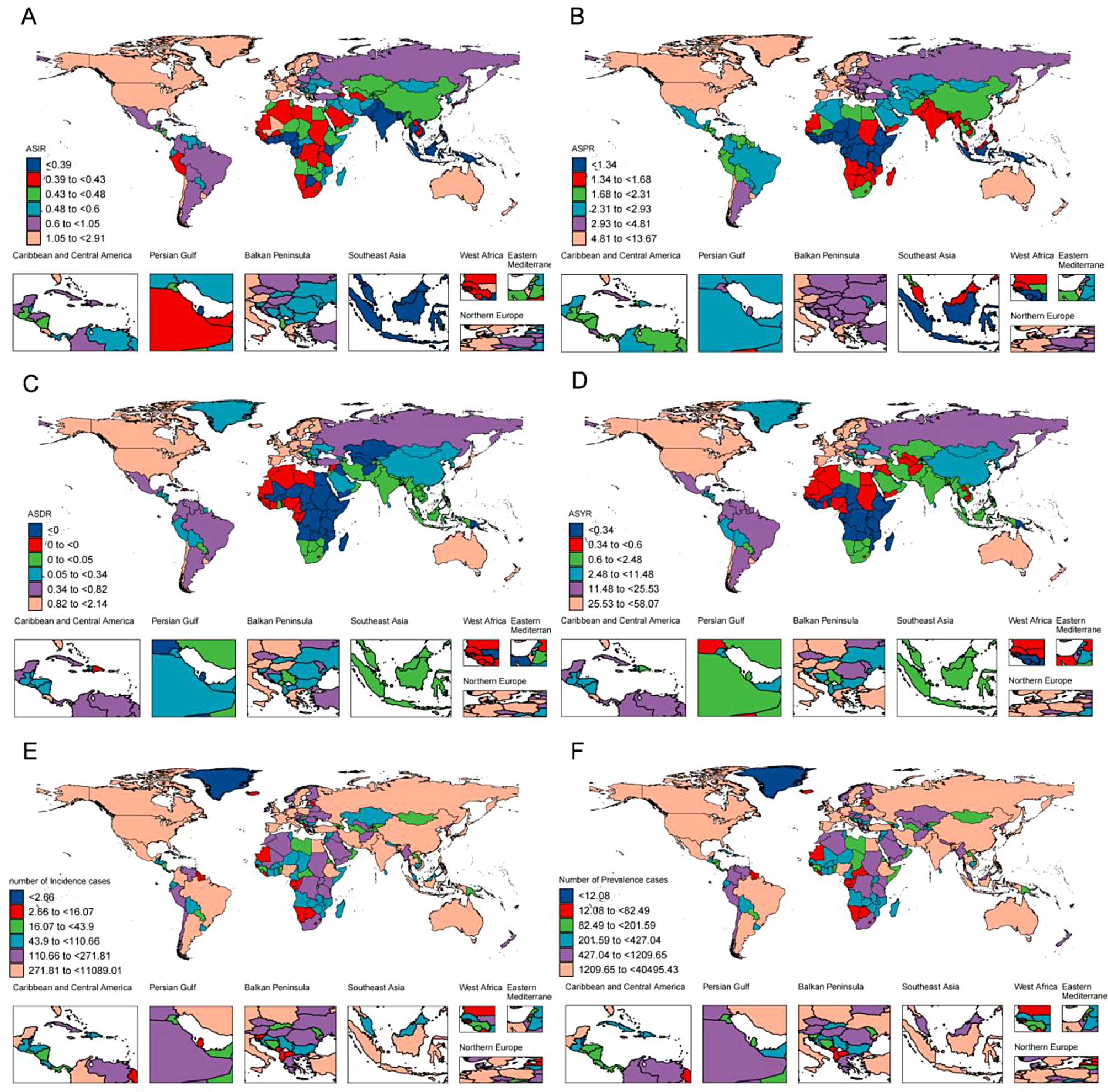

The MMS implementation in each province is considered highly cost-effective. The ICER of each province in Indonesia is presented in a cost-effectiveness league table (supplementary material 2). Nevertheless, determining priority coverage areas is crucial due to budget constraints and significant disparities in monetary value across different provinces.46 The resource and budget allocation applied to the national ICER as a cost-effectiveness cut-off value. Provinces prioritized for the introduction of MMS in Indonesia are those with ICER values lower than the national ICER value (USD 10 per DALY averted). Therefore, the implementation of the MMS program is recommended to be prioritized in 18 provinces: Southwest Papua, Highlands Papua, Bali, West Java, South Kalimantan, North Maluku, West Papua, Aceh, North Sumatra, Central Java, Central Kalimantan, West Sulawesi, Maluku, Yogyakarta, East Java, North Kalimantan, South Sulawesi, and South Papua as illustrated in Table 3 and Figure 1.

|

Table 3 Cost-Effectiveness League Table

|

|

Figure 1 Priority setting for the MMS Program in Indonesia.

|

Sensitivity Analysis

Related to the sensitivity analysis, MMS cost and IFA cost seemed to be the most influential variables affecting the cost-effectiveness value in the implementation of MMS. Other variables that importantly influence the cost-effectiveness value are stillbirth, life expectancy (at birth), neonatal mortality (female), preterm birth, and small gestational age as presented in a tornado chart (Figure S2).

Discussion

Insufficient maternal nutritional intake significantly contributes to adverse birth outcomes.1,8,10,11 The WHO has advocated for the supplementation of pregnant women with MMS since 2016 to decrease the risk of numerous complications.9 Our findings show that the projected positive impacts of transitioning from IFA to MMS resulted in reduced mortality rates and adverse birth outcomes. The monetary investment necessary to realize these improvements indicates a cost-effective outcome. Additionally, priority setting based on cost-effectiveness was considered a reasonable option to guide decision-makers in resource allocation to maximize health outcomes, serving as a key consideration in strategic planning for achieving universal health coverage.48,49 Furthermore, the outcomes exhibited stability throughout one-way deterministic sensitivity analyses, indicating that these conclusions were reliable.

Assuming that all pregnant women adhere to a regimen of 180 pills throughout their pregnancies, the transition from IFA to MMS is projected to 54,897 (44% coverage scenario) and 124,766 (100% coverage scenario) DALYs would be averted in Indonesia. The difference in DALYs averted between the 44% and 100% coverage scenarios is attributable to the differing number of women who benefit from the intervention in each case. With 100% coverage, a greater percentage of pregnant women receive MMS, resulting in a more significant overall decrease in negative maternal and neonatal health outcomes, thus yielding higher DALY estimates. Consuming 180 MMS tablets has played an essential role in pregnant women from early pregnancy in human reproduction, facilitating gametogenesis, fertilization, embryogenesis, placental development, function, redox balance, and vascularization.19–21,50 The growth and function of the placenta are crucial throughout pregnancy to reduce the risk of LBW (14%). MMS demonstrates improved mitochondrial function, which is associated with a reduced risk of premature birth (14%). MMS contributes to hemoglobin metabolism, thus decreasing the risk of anemia in pregnancy. MMS effectively reduces the risk of infant mortality (18%).1,8,10,11,50,51 It is crucial to highlight that, even at existing coverage levels, significant reductions in maternal and child mortality and morbidity are projected in Indonesia if there is high adherence to the prescribed amount of tablets.14 Adherence level is crucial for maximizing the health advantages of MMS intervention20 since medication non-adherence has been identified as a major contributor to health issues and economic burden.52 A report concerning the previous IFA program in Indonesia shows that the adherence rate for the consumption of 90 IFA tablets is merely 44%.33 Consequently, adherence to MMS consumption will be a potential challenge that must be addressed.

As a country considering investment in MMS, Indonesia requires an assessment of the cost-effectiveness of transitioning from IFA to MMS.29 The MMS cost-benefit tool was utilized to quickly calculate predictions regarding maternal and child health outcomes, as well as the cost-effectiveness of MMS in comparison to IFA for pregnant women. The MMS cost-benefit tool works as an evidence-based modeling instrument designed to facilitate national and international policymakers’ access to data that aids in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of transitioning from IFA to MMS for pregnant women. The MMS cost-benefit tool presents a valuable resource for countries to perform comprehensive, sub-national, and ongoing analyses within the framework of implementation research on MMS.31

Our findings prove that transitioning from IFA to MMS is highly cost-effective based on the threshold of one to three times Indonesia’s GDP per capita, in the absence of country-specific thresholds.53 Our analysis shows that the implementation of MMS under both 44% and 100% coverage scenarios produced an equal ICER value of USD 10 per DALY averted at the national level. The ICER is consistent across the two scenarios, as it is defined as the additional cost per DALY averted in relation to IFA supplementation. The proportional scaling of both costs and effects with coverage in the modeling framework ensures that the ratio of incremental costs to health benefits remains constant. This demonstrates the difference in the absolute number of DALYs between the two scenarios, despite the constancy of the ICER. The spending required to achieve these improvements, which is below one GDP per capita (USD 4870.13) in 2024, signifies a favorable cost-benefit ratio. Cost-effectiveness analysis provides a quantitative evaluation of both current and prospective efficiency in a health system.49 The cost-effectiveness of the IFA-MMS transition in reducing maternal and child mortality and morbidity (eg, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, LBW, preterm births, stillbirth, and SGA) has proven beneficial. Given that most lives saved would occur in the early stages of life, the policy of transitioning from IFA to MMS is worthy of consideration.

Currently, MMS is in the initial phases of implementation in Indonesia. The findings of this study support decision-making on the possibility of MMS being expanded as a key focus within Indonesia’s national health program, serving as a primary strategy for lowering the risk of numerous complications in pregnant women.48,49,54 The findings of this study align with previous studies conducted in Bangladesh,14,26–28 Burkina Faso,14 Pakistan,28,29 India,28,29 Mali,29 and Tanzania,29 which indicated that transitioning from IFA to MMS is considered a cost-effective intervention to enhance maternal and child health. This is the first study conducted in Indonesia addressing this issue.

Related to the sensitivity analyses, the results in this study showed that the cost-effectiveness value was sensitive to changes in MMS cost. Numerous variables can influence MMS costs, including procurement regulations, the volume, and consistency of purchasing bargains with tablet ingredient suppliers, packaging methods, and tablet quantities.14,18,36,55–57 Consequently, the introduction of MMS at accessible costs is essential, particularly for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Indonesia.55 Scale economies in tablet production are crucial therefore, the domestic manufacture of MMS in Indonesia should be initiated to provide a consistent, affordable, and high‐quality supply of MMS, while supporting the expansion of MMS coverage.14,58 Domestic manufacture of MMS could be accomplished by following the standards established by the MMS Technical Advisory Group, alongside a comprehensive technical understanding of the manufacturing prerequisites for the UNIMMAP–MMS product, and the methodologies to ensure that the produced product achieves its expected quality.14,18

As Islam is the major religion among Indonesia’s population, ensuring halal compliance is essential. The UNIMMAP–MMS product can be produced in compliance with Halal standards established by local authorities.18 Indonesia is home to over 207 million Muslims, representing 87.2% of the population.59 Halal is an essential concept for Muslim consumers concerning the products they consume, including pharmaceutical ingredients. In contemporary medicine, these ingredients must be completely free of porcine (0%) and contain less than 1% alcohol.60,61

In October 2024, the Indonesian Ministry of Health announced the immediate initiation of MMS in Indonesia, a program currently in its early stages.22–24 Switching from IFA to MMS tablets in Indonesia may require several years and substantial resources, particularly personnel and budgetary expenditure, given the country’s expansive territory and dense population.25 Due to logistical and budget limitations, determining priority coverage areas is essential to mitigate the disease burden associated with nutritional deficiencies among pregnant women. This involves identifying higher-risk groups and regions where preventive measures are expected to be most effective, thereby maximizing public health returns on investment.20,46

Priority settings should focus on optimizing population health, and the availability of further knowledge regarding cost-effectiveness will enhance decision-making and result in improved health outcomes as one consideration in strategic planning.48,49 Cost-effectiveness evidence in each province enables policy-makers to assess the effective and efficient use of available resources. It also guides optimal investment strategies to meet health targets and achieve universal health coverage within the constraints of limited resources, ensuring the optimal allocation of financial resources in the healthcare sector.38,49 Universal health coverage signifies that every individual has access to a comprehensive array of quality health services as required, without experiencing financial difficulties.62 Based on the results of the cost-effectiveness analysis, it’s recommended to prioritize introducing the MMS program in 18 provinces where the ICER is below Indonesia’s national ICER of USD 10. The analysis commences with the province exhibiting the lowest ICERs, subsequently advancing to those with higher ICERs in the rank order.43 Public health strategies prioritize introducing MMS programs, especially in provinces with poor maternal health outcomes. Expanding MMS programs in LMICs necessitates advancements in supply chain logistics and improved availability and access to health services.15,63 The prioritization of MMS implementation allows for the distribution of healthcare resources under the strategies, starting with the province exhibiting the lowest cost-effectiveness and subsequently advancing to those with higher cost-effectiveness in the ranking.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to assess cost-effectiveness analysis regarding the transition from IFA to MMS during pregnancy in Indonesia at the national and sub-national levels (38 provinces). The primary strength of this study is the use of country-specific data, which enables policymakers to make informed decisions regarding finance and resource allocation by prioritizing selected coverage areas in MMS implementation. Specifically, MMS programs have not yet been included in the national healthcare insurance coverage unit, and our study offers valuable insights into the implications of their potential inclusion. With regards to the shifting from IFA to MMS supplementation in Indonesia, our cost-effectiveness study demonstrates that the implementation of MMS is more advantageous than IFA, aligning with the WHO’s recommendation to improve the quality of maternal and child health.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. The first limitation concerns a proposed transition cost that has been estimated based on population size to assess context-specific expenses associated with initiating a new program. These expenses include developing training components, establishing new policies and regulations, and training healthcare personnel; however, actual costs may differ. In the absence of more reliable data on transition costs, we perform a costing exercise for transition activities informed by a published article on the cost-effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving maternal, newborn, and child health outcomes: a WHO Choosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective (CHOICE) analysis for Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia.38 Consequently, we may have underestimated the transition cost. As for the second limitation, this study did not address MMS adherence. The analysis presumes that all “covered” pregnant women receive and take precisely 180 tablets. Achieving all consumption of a precise dosage of tablets by all covered women will be challenging and does not seem to occur systematically. Some pregnant women may take fewer than 180 tablets. Referring to the previous IFA program in Indonesia, a study indicates that the adherence level to the consumption of 90 IFA tablets is only 44%.33 The costs associated with transitioning from IFA to MMS will rise, while the expected benefits will remain unchanged. Further attempts are required to address these issues. The third limitation is that the modeling tool for cost-benefit analysis, developed by Nutrition International, does not allow the inclusion of additional maternal health parameters that could be significant for assessing the effectiveness of MMS in pregnant women. The model focuses on health outcomes of interest, as identified in two published reviews, Keats et al, 201940 and Smith et al, 2017.41 The fourth limitation is that probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) cannot be performed using the open-access online MMS cost-benefit tool developed by Nutrition International because the tool is designed primarily to provide deterministic estimates based on fixed input parameters rather than full probabilistic modeling. While the tool incorporates rigorous methodologies to estimate health impacts, costs, and cost-effectiveness, it does not support Monte Carlo simulations or the input of probability distributions for parameters that allow quantification of uncertainty across multiple model inputs simultaneously. However, the deterministic approach can be used to provide clear, interpretable results such as benefit-cost ratios and incremental cost per DALY averted based on fixed assumptions, but without performing full probabilistic uncertainty analysis. More complex PSA requiring simulation of parameter distributions and joint uncertainty are typically conducted offline using statistical software, as seen in some detailed cost-effectiveness studies of MMS interventions. Thus, while the tool does conduct some sensitivity analyses by varying key assumptions, full probabilistic sensitivity analysis is not supported in its open-access online version.

This study provides recommendations for policymakers in Indonesia to decide on following comprehensive policies to improve maternal and child health outcomes. Health enhancements throughout gestation and early childhood might lower the likelihood of poor health and disease, hence supporting life expectancy.64 The additional budgetary requirement poses significant challenges to implement in a country with constrained healthcare budgets for maternal and child health programs. The MMS implementation strategy could start with a 44% coverage scenario across 18 prioritized provinces and gradually expand to 100% coverage for all pregnant women in Indonesia. This approach is critical for transitioning from the IFA to the MMS program. Transitioning from IFA to MMS represents the ideal approach for enhancing maternal and child health outcomes.54 We are encouraged that the reviewer acknowledges the policy relevance of our findings and their potential to inform resource allocation and program planning for maternal nutrition interventions. Further study is required to incorporate a concise perspective on the necessity of supplementary qualitative or operational studies, which could highlight the significance of converting economic findings into practical implementation.

Conclusions

This study showed the ICER value of USD 10 per DALY averted for both scenarios (44% and 100% coverage), concluding that the transition from IFA to the MMS program was confirmed to be a highly cost-effective intervention. These results should facilitate decision-making that prioritizes maternal and child health. The MMS implementation strategy could start with a 44% coverage scenario across 18 prioritized provinces and gradually expand to 100% coverage for all pregnant women in Indonesia. This strategy is essential for the transition from the IFA to the MMS program in Indonesia. It is essential to identify several potential barriers to the implementation of the MMS program in Indonesia, including the adequacy of supply chain logistics, the improvement of health service availability and access, and the need for better adherence to MMS consumption.

Ethical Clearance

Data were obtained from publicly accessible documents, and human participants were not involved in this investigation. Consequently, ethical considerations regarding human participants were not necessary. Nevertheless, efforts were made to guarantee that the data were collected and analyzed in a manner that was both ethical and transparent.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Massari M, Novielli C, Mandò C, et al. Multiple micronutrients and docosahexaenoic acid supplementation during pregnancy: a randomized controlled study. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):1–16. doi:10.3390/nu12082432

2. Bourassa MW, Osendarp SJM, Adu-Afarwuah S, et al. Review of the evidence regarding the use of antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation in low- and middle-income countries. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 1444. The New York Academy of Sciences, New York, NY, United States:Blackwell Publishing Inc.;2019:6–21. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85066409444&doi=10.1111%2Fnyas.14121&partnerID=40&md5=50806e658b69069ee0e9fe036cffc927.

3. Tuncalp Ö, Rogers LM, Lawrie TA, et al. WHO recommendations on antenatal nutrition: an update on multiple micronutrient supplements. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5(7):e003375. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003375

4. Gomes F, Askari S, Black RE, et al. Antenatal multiple micronutrient supplements versus iron-folic acid supplements and birth outcomes: analysis by gestational age assessment method. Matern Child Nutr. 2023;19(3). doi:10.1111/mcn.13509

5. Kesehatan RIK. Profil kesehatan Indonesia tahun 2020. Kementerian Kesehatan republik Indonesia: 2021.

6. Manfredini M. The effects of nutrition on maternal mortality: evidence from 19th-20th century Italy. SSM – Popul Heal. 2020;12:100678. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100678

7. Bakshi RK, Kumar N, Srivastava A, et al. Decadal trends of maternal mortality and utilization of maternal health care services in India: evidence from nationally representative data. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2025;14(5):1807. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_916_24

8. Berti C, Gaffey MF, Bhutta ZA, Cetin I. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation: evidence from large-scale prenatal programmes on coverage, compliance and impact. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14 Suppl 5(Suppl 5):e12531. doi:10.1111/mcn.12531

9. World Health Organization. WHO antenatal care recommendations for a positive pregnancy experience. nutritional intervention update: multiple micronutrient supplements during pregnancy. World Health Organization: 2020.

10. Petry CJ, Ong KK, Hughes IA, Dunger DB. Multiple micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy and increased birth weight and skinfold thicknesses in the offspring: the Cambridge baby growth study. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):1–13. doi:10.3390/nu12113466

11. Priliani L, Prado EL, Restuadi R, Waturangi DE, Shankar AH, Malik SG. Maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation stabilizes mitochondrial DNA copy number in pregnant women in Lombok, Indonesia. J Nutr. 2019;149(8):1309–1316. doi:10.1093/jn/nxz064

12. Sudfeld CR, Bliznashka L, Salifou A, et al. Evaluation of multiple micronutrient supplementation and medium-quantity lipidbased nutrient supplementation in pregnancy on child development in rural Niger: a secondary analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2022;19(5):1–17. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003984

13. Moore SE, Fulford AJ, Darboe MK, Jobarteh ML, Jarjou LM, Prentice AM. A randomized trial to investigate the effects of pre-natal and infant nutritional supplementation on infant immune development in rural Gambia: the ENID trial: early nutrition and immune development. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):107. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-107

14. Engle-Stone R, Kumordzie SM, Meinzen-Dick L, Vosti SA. Replacing iron-folic acid with multiple micronutrient supplements among pregnant women in Bangladesh and Burkina Faso: costs, impacts, and cost-effectiveness. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 1444. Department of Nutrition, University of California – Davis, Davis, CA, United States:Blackwell Publishing Inc.;2019:35–51. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85065195150&doi=10.1111%2Fnyas.14132&partnerID=40&md5=01f9ee9fec236784fb85abdc3703bf3c.

15. MMS TAG. Focusing on multiple micronutrient supplements in pregnancy: second edition. update on the scientific evidence on the benefits of prenatal multiple micronutrient supplements. 2023: 15–22. Available from: https://d2b2stjpsnac9i.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/202305-MMS-2-sightandlife.pdf#page=15. Accessed November 04, 2025.

16. Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11(11):CD004905. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004905.pub3

17. Schaefer E, Nock D. The impact of preconceptional multiple-micronutrient supplementation on female fertility. Clin Med Insights Women’s Heal. 2019;12:1179562X1984386.

18. MMS-TAG, MNF. Expert consensus on an open-access united nations international multiple micronutrient antenatal preparation-multiple micronutrient supplement product specification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1470(1):3–13. doi:10.1111/nyas.14322

19. Mei Z, Jefferds ME, Namaste S, Suchdev PS, Flores-Ayala RC. Monitoring and surveillance for multiple micronutrient supplements in pregnancy. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(April 2017):1–9. doi:10.1111/mcn.12501

20. Gomes F, Bourassa MW, Adu-Afarwuah S, et al. Setting research priorities on multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1465(1):76–88. doi:10.1111/nyas.14267

21. Schulze KJ, Gernand AD, Khan AZ, et al. Newborn micronutrient status biomarkers in a cluster-randomized trial of antenatal multiple micronutrient compared with iron folic acid supplementation in rural Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(5):1328–1337. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa223

22. Kemenkes R. Keputusan menteri kesehatan republik indonesia nomor HK.01.07/MENKES/1092/2024 tentang standar suplemen zat gizi mikro untuk ibu hamil. 2024: 1–8.

23. Vitamin Angels. How Indonesia is transforming maternal nutrition with MMS | vitamin angels. 2024. Available from: https://vitaminangels.org/news/how-indonesia-is-transforming-maternal-nutrition-with-mms/. Accessed March 5, 2025.

24. Menkes tekankan pentingnya ragam mikronutrien bagi ibu hamil. Available from: https://kemkes.go.id/id/rilis-kesehatan/menkes-tekankan-pentingnya-ragam-mikronutrien-bagi-ibu-hamil. Accessed March 7, 2025.

25. Meinzen-dick L, Vosti SA. The evidence base cost-effectiveness of replacing iron-folic acid with multiple micronutrient supplements.

26. Svefors P, Selling KE, Shaheen R, Khan AI, Persson L-Å, Lindholm L. Cost-effectiveness of prenatal food and micronutrient interventions on under-five mortality and stunting: analysis of data from the MINIMat randomized trial. Bangladesh PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0191260.

27. Shaheen R, Persson LÅ, Ahmed S, Streatfield PK, Lindholm L. Cost-effectiveness of invitation to food supplementation early in pregnancy combined with multiple micronutrients on infant survival: analysis of data from MINIMat randomized trial, Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):125. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0551-y

28. Kashi B, Godin CM, Kurzawa ZA, Verney AMJ, Busch-Hallen JF, De-Regil LM. Multiple micronutrient supplements are more cost-effective than iron and folic acid: modeling results from 3 high-burden Asian countries. J Nutr. 2019;149(7):1222–1229. doi:10.1093/jn/nxz052

29. Young N, Bowman A, Swedin K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of antenatal multiple micronutrients and balanced energy protein supplementation compared to iron and folic acid supplementation in India, Pakistan, Mali, and Tanzania: a dynamic microsimulation study. PLoS Med. 2022;19(2):e1003902. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003902

30. MMS cost-benefit tool – nutrition international. Available from: https://www.nutritionintl.org/learning-resources-home/mms-cost-benefit-tool/. Accessed March 17, 2025.

31. Verney AMJ, Busch-Hallen JF, Walters DD, Rowe SN, Kurzawa ZA, Arabi M. Multiple micronutrient supplementation cost-benefit tool for informing maternal nutrition policy and investment decisions. Matern Child Nutr. 2023;19(4):e13523. doi:10.1111/mcn.13523

32. Interface U, Guide I. The MMS Cost-Benefit Tool. 2019.

33. Kemenkes R. Survei Kesehatan Indonesia (SKI) 2023. Kemenkes RI; 2023.

34. Viscusi WK, Masterman CJ. Income elasticities and global values of a statistical life. J Benefit-Cost Anal. 2017;8(2):226–250. doi:10.1017/bca.2017.12

35. Robinson LA, Hammitt JK, Cecchini M, et al. Reference case guidelines for benefit-cost analysis in global health and development. SSRN Electron J. 2022;(May).

36. UNICEF. Multiple Micronutrient Powder Supply and Market Update. Copenhagen, Denmark: UNICEF Supply Division; 2021.

37. Kemenkes R. Nilai klaim harga obat program rujuk balik, obat penyakit kronis di fasilitas kesehatan rujukan tingkat lanjutan, obat kemoterapi, dan obat alteplase. keputusan menteri kesehat republik indones no HK0107/MENKES/1905/2023. 2023: 1–58.

38. Stenberg K, Watts R, Bertram MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve maternal, newborn and child health outcomes: a WHO-CHOICE analysis for Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2021;10(11):706–723.

39. Johns B, Baltussen R, Hutubessy R. Programme costs in the economic evaluation of health interventions. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2003;1(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/1478-7547-1-1

40. Keats EC, Haider BA, Tam E, Bhutta ZA. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(3).

41. Smith ER, Shankar AH, Wu LS, et al. Modifiers of the effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on stillbirth, birth outcomes, and infant mortality: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 17 randomised trials in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Heal. 2017;5(11):e1090–100. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30371-6

42. Kementrian Kesehatan. Profil kesehatan Indonesia 2023. 2024: 550.

43. Mauskopf J, Rutten F, Schonfeld W. Cost-effectiveness league tables. Valuable guidance for decision makers? PharmacoEconomics – Ital Res Artic. 2004;6(3):131–140. doi:10.1007/BF03320631

44. Zakiyah N, van Asselt ADI, Setiawan D, Cao Q, Roijmans F, Postma MJ. Cost-effectiveness of scaling up modern family planning interventions in low- and middle-income countries: an economic modeling analysis in Indonesia and Uganda. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(1):65–76. doi:10.1007/s40258-018-0430-6

45. Indonesia B. Statistik Indonesia Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2024. Vol. 1101001. BPS-Statistics Indonesia; 2024:790.

46. Mori AT, Robberstad B. Pharmacoeconomics and its implication on priority-setting for essential medicines in Tanzania: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12(1):1. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-12-110

47. Produk domestik regional bruto per kapita atas dasar harga berlaku menurut provinsi (ribu rupiah), 2024 – tabel statistik – badan pusat statistik Indonesia. Available from: https://www.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/3/YWtoQlRVZzNiMU5qU1VOSlRFeFZiRTR4VDJOTVVUMDkjMw==/produk-domestik-regional-bruto-per-kapita-atas-dasar-harga-berlaku-menurut-provinsi–ribu-rupiah-2022.html?year=2023. Accessed June 18, 2025.

48. Baltussen R, Jansen MP, Mikkelsen E, et al. Priority setting for universal health coverage: we need evidence-informed deliberative processes, not just more evidence on cost-effectiveness. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2016;5(11):615–618. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.83

49. Bertram MY, Lauer JA, Stenberg K, Edejer TTT. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care interventions for priority setting in the health system: an update from WHO CHOICE. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2021;10(11):673–677.

50. Bourassa MW, Osendarp SJM, Adu-Afarwuah S, et al. Review of the evidence regarding the use of antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation in low- and middle-income countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1444(1):6–21. doi:10.1111/nyas.14121

51. Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):CD004905. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004905.pub5

52. Octaviani P, Ikawati Z, Yasin NM, Kristina SA, Kusuma IY. Interventions to improve adherence to medication on multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients: a scoping review. Med J Malaysia. 2024;79(2):212–221.

53. Marseille E, Larson B, Kazi DS, Kahn JG, Rosen S. Thresholds for the cost–effectiveness of interventions: alternative approaches. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(2):118–124. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.138206

54. Alfiani F, Meita Utami A, Zakiyah N, Aizati Athirah Daud N, Suwantika AA, Puspitasari IM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of multiple micronutrient supplementation (MMS) compared to iron folic acid (IFA) in pregnancy: a systematic review. Int J Womens Health. 2025;17:639–649. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S489159

55. Zakiyah N, Insani WN, Suwantika AA, van der Schans J, Postma MJ. Pneumococcal vaccination for children in Asian countries: a systematic review of economic evaluation studies. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):1–18. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030426

56. Paulden M, O’Mahony J, McCabe C. Determinants of Change in the Cost-effectiveness Threshold. Med Decis Mak. 2017;37(2):264–276. doi:10.1177/0272989X16662242

57. Garcia-Casal MN, Estevez D, De-Regil LM. Multiple micronutrient supplements in pregnancy: implementation considerations for integration as part of quality services in routine antenatal care. Objectives, results, and conclusions of the meeting. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(S5). doi:10.1111/mcn.12704

58. Monterrosa EC, Beesabathuni K, van Zutphen KG, et al. Situation analysis of procurement and production of multiple micronutrient supplements in 12 lower and upper middle-income countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(S5). doi:10.1111/mcn.12500

59. Laman resmi republik Indonesia • Portal informasi Indonesia. Available from: https://indonesia.go.id/profil/agama. Accessed March 15, 2025.

60. Herdiana Y, Sofian FF, Shamsuddin S, Rusdiana T. Towards halal pharmaceutical: exploring alternatives to animal-based ingredients. Heliyon. 2023;10(1). doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23624

61. Pemerintah Indonesia. Peraturan presiden (PERPRES) nomor 6 tahun 2023 tentang sertifikasi halal obat, produk biologi, dan alat kesehatan. Perpres Nomor. 2023;(148729):1–17.

62. World Health Organization. Universal health coverage (UHC). 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-uhc. Accessed March 13, 2025.

63. Shekar M, Kakietek J, Dayton EJ, Walters D. An investment framework for nutrition. 2016.

64. Dundas R, Boroujerdi M, Browne S, et al. Evaluation of the Healthy Start voucher scheme on maternal vitamin use and child breastfeeding: a natural experiment using data linkage. Public Heal Res. 2023;11(11):1–101.