Yang YL, Yang F, Huang ZQ, Li YY, Shi HY, Sun Q, et al. T cells, NK cells, and tumor-associated macrophages in cancer immunotherapy and the current state of the art of drug delivery systems. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1199173.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Shen X, Zhou S, Yang Y, Hong T, Xiang Z, Zhao J, et al. TAM-targeted re-education for enhanced cancer immunotherapy: mechanism and recent progress. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1034842.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Kim SK, Cho SW. The evasion mechanisms of cancer immunity and drug intervention in the tumor microenvironment. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:868695.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Bai R, Cui J. Development of immunotherapy strategies targeting tumor microenvironment is fiercely ongoing. Front Immunol. 2022;13:890166.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Bol KF, Schreibelt G, Gerritsen WR, De Vries IJ, Figdor CG. Dendritic cell–based immunotherapy: state of the art and beyond. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(8):1897–906.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Tai Y, Chen M, Wang F, Fan Y, Zhang J, Cai B, et al. The role of dendritic cells in cancer immunity and therapeutic strategies. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;128:111548.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Wculek SK, Cueto FJ, Mujal AM, Melero I, Krummel MF, Sancho D. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(1):7–24.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Yu J, Sun H, Cao W, Song Y, Jiang Z. Research progress on dendritic cell vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2022;11(1):3.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Taefehshokr S, Parhizkar A, Hayati S, Mousapour M, Mahmoudpour A, Eleid L, et al. Cancer immunotherapy: Challenges and limitations. Pathology-Research and Practice. 2022;229:153723.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Perez CR, De Palma M. Engineering dendritic cell vaccines to improve cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5408.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Joffre OP, Segura E, Savina A, Amigorena S. Cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(8):557–69.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Wakim LM, Bevan MJ. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471(7340):629–32.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Marino J, Babiker-Mohamed MH, Crosby-Bertorini P, Paster JT, LeGuern C, Germana S, Abdi R, Uehara M, Kim JI, Markmann JF, Tocco G. Donor exosomes rather than passenger leukocytes initiate alloreactive T cell responses after transplantation. Sci Immunol. 2016;1(1):aaf8759.

Saccheri F, Pozzi C, Avogadri F, Barozzi S, Faretta M, Fusi P, Rescigno M. Bacteria-induced gap junctions in tumors favor antigen cross-presentation and antitumor immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(44):44ra57.

Mendoza-Naranjo A, Saéz PJ, Johansson CC, Ramírez M, Mandakovic D, Pereda C, et al. Functional gap junctions facilitate melanoma antigen transfer and cross-presentation between human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):6949–57.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Roche PA, Furuta K. The ins and outs of MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(4):203–16.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Wang GZ, Tang XD, Lü MH, Gao JH, Liang GP, Li N, et al. Multiple antigenic peptides of human heparanase elicit a much more potent immune response against tumors. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4(8):1285–95.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Sika-Paotonu D. Increasing the potency of dendritic cell-based vaccines for the treatment of cancer (Doctoral dissertation, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington). 2014.

Sánchez-León ML, Jiménez-Cortegana C, Cabrera G, Vermeulen EM, de la Cruz-Merino L, Sánchez-Margalet V. The effects of dendritic cell-based vaccines in the tumor microenvironment: impact on myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1050484.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

MacDonald KP, Munster DJ, Clark GJ, Dzionek A, Schmitz J, Hart DN. Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2002;100(13):4512–20.

CAS

Google Scholar

Liu YJ. Dendritic cell subsets and lineages, and their functions in innate and adaptive immunity. Cell. 2001;106(3):259–62.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Böttcher JP, Sousa CR. The role of type 1 conventional dendritic cells in cancer immunity. Trends Cancer. 2018;4(11):784–92.

Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31(1):563–604.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Schlitzer A, McGovern N, Ginhoux F. Dendritic cells and monocyte-derived cells: two complementary and integrated functional systems. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;41:9–22.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Lee KW, Yam JW, Mao X. Dendritic cell vaccines: a shift from conventional approach to new generations. Cells. 2023;12(17):2147.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Higano CS, Schellhammer PF, Small EJ, Burch PA, Nemunaitis J, Yuh L, Provost N, Frohlich MW. Integrated data from 2 randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trials of active cellular immunotherapy with sipuleucel‐T in advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Interdisc Int J Am Cancer Soc. 2009;115(16):3670–9.

Cheever MA, Higano CS. PROVENGE (Sipuleucel-T) in prostate cancer: the first FDA-approved therapeutic cancer vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(11):3520–6.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–22.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Ratzinger G, Baggers J, de Cos MA, Yuan J, Dao T, Reagan JL, et al. Mature human Langerhans cells derived from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors stimulate greater cytolytic T lymphocyte activity in the absence of bioactive IL-12p70, by either single peptide presentation or cross-priming, than do dermal-interstitial or monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(4):2780–91.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Chung DJ, Carvajal RD, Postow MA, Sharma S, Pronschinske KB, Shyer JA, et al. Langerhans-type dendritic cells electroporated with TRP-2 mRNA stimulate cellular immunity against melanoma: results of a phase I vaccine trial. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(1):e1372081.

Article

Google Scholar

Laoui D, Keirsse J, Morias Y, Van Overmeire E, Geeraerts X, Elkrim Y, et al. The tumor microenvironment harbours ontogenically distinct dendritic cell populations with opposing effects on tumor immunity. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):13720.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Mastelic-Gavillet B, Balint K, Boudousquie C, Gannon PO, Kandalaft LE. Personalized dendritic cell vaccines—recent breakthroughs and encouraging clinical results. Front Immunol. 2019;11(10):766.

Article

Google Scholar

Tel J, Benitez-Ribas D, Hoosemans S, Cambi A, Adema GJ, Figdor CG, et al. DEC-205 mediates antigen uptake and presentation by both resting and activated human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(4):1014–23.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Bonifaz L, Bonnyay D, Mahnke K, Rivera M, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. Efficient targeting of protein antigen to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205 in the steady state leads to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class I products and peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2002;196(12):1627–38.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Naseri M, Bozorgmehr M, Zöller M, Ranaei Pirmardan E, Madjd Z. Tumor-derived exosomes: the next generation of promising cell-free vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1779991.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Gu L, Mooney DJ. Biomaterials and emerging anticancer therapeutics: engineering the microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(1):56–66.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Ali OA, Huebsch N, Cao L, Dranoff G, Mooney DJ. Infection-mimicking materials to program dendritic cells in situ. Nat Mater. 2009;8(2):151–8.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Gentile P, Chiono V, Carmagnola I, Hatton PV. An overview of poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA)-based biomaterials for bone tissue engineering. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(3):3640–59.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Bencherif SA, Sands RW, Bhatta D, Arany P, Verbeke CS, Edwards DA, et al. Injectable preformed scaffolds with shape-memory properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(48):19590–5.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Long GV, Dummer R, Hamid O, Gajewski TF, Caglevic C, Dalle S, et al. Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab versus placebo plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma (ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(8):1083–97.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Warren S, Adjemian S, Agostinis P, Martinez AB, et al. Consensus guidelines for the definition, detection and interpretation of immunogenic cell death. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000337.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Vedunova M, Turubanova V, Vershinina O, Savyuk M, Efimova I, Mishchenko T, et al. DC vaccines loaded with glioma cells killed by photodynamic therapy induce Th17 antitumor immunity and provide a four-gene signature for glioma prognosis. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(12):1062.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Wang X, Ji J, Zhang H, Fan Z, Zhang L, Shi L, et al. Stimulation of dendritic cells by DAMPs in ALA-PDT treated SCC tumor cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(42):44688.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Gu YZ, Zhao X, Song XR. Ex vivo pulsed dendritic cell vaccination against cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(7):959–69.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Aarntzen EH, Schreibelt G, Bol K, Lesterhuis WJ, Croockewit AJ, De Wilt JH, et al. Vaccination with mRNA-electroporated dendritic cells induces robust tumor antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells responses in stage III and IV melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(19):5460–70.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Kreiter S, Selmi A, Diken M, Sebastian M, Osterloh P, Schild H, et al. Increased antigen presentation efficiency by coupling antigens to MHC class I trafficking signals. J Immunol. 2008;180(1):309–18.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Dannull J, Nair S, Su Z, Boczkowski D, DeBeck C, Yang B, et al. Enhancing the immunostimulatory function of dendritic cells by transfection with mRNA encoding OX40 ligand. Blood. 2005;105(8):3206–13.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Tcherepanova IY, Adams MD, Feng X, Hinohara A, Horvatinovich J, Calderhead D, et al. Ectopic expression of a truncated CD40L protein from synthetic post-transcriptionally capped RNA in dendritic cells induces high levels of IL-12 secretion. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9(1):90.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Carneiro BA, Zamarin D, Marron T, Mehmi I, Patel SP, Subbiah V, El-Khoueiry A, Grand D, Garcia-Reyes K, Goel S, Martin P. Abstract CT183: first-in-human study of MEDI1191 (mRNA encoding IL-12) plus durvalumab in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2022 Jun 15;82(12_Supplement):CT183-.

Pitt JM, André F, Amigorena S, Soria JC, Eggermont A, Kroemer G, et al. Dendritic cell–derived exosomes for cancer therapy. J Clin Investig. 2016;126(4):1224–32.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Fu C, Peng P, Loschko J, Feng L, Pham P, Cui W, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells cross-prime naive CD8 T cells by transferring antigen to conventional dendritic cells through exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(38):23730–41.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Dai Phung C, Pham TT, Nguyen HT, Nguyen TT, Ou W, Jeong JH, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody-functionalized dendritic cell-derived exosomes targeting tumor-draining lymph nodes for effective induction of antitumor T-cell responses. Acta Biomater. 2020;1(115):371–82.

Article

Google Scholar

Mohammadzadeh Y, De Palma M. Boosting dendritic cell nanovaccines. Nat Nanotechnol. 2022;17(5):442–4.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Chen J, Duan Y, Che J, Zhu J. Dysfunction of dendritic cells in tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy. Cancer Commun. 2024;44(9):1047–70.

Article

Google Scholar

Stevens D, Ingels J, Van Lint S, Vandekerckhove B, Vermaelen K. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy in lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;11:620374.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Zheng J, Li X, He A, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Dang M, et al. In situ antigen-capture strategies for enhancing dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. J Control Release. 2025;29:113984.

Article

Google Scholar

Ng YH, Chalasani G. Role of secondary lymphoid tissues in primary and memory T-cell responses to a transplanted organ. Transplant Rev. 2010;24(1):32–41.

Article

Google Scholar

Sharma S, Stolina M, Luo J, Strieter RM, Burdick M, Zhu LX, et al. Secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine mediates T cell-dependent antitumor responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164(9):4558–63.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

von Renesse J, Lin MC, Ho PC. Tumor-draining lymph nodes–friend or foe during immune checkpoint therapy? Trends Cancer. 2025.

Böttcher JP, Bonavita E, Chakravarty P, Blees H, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Sammicheli S, Rogers NC, Sahai E, Zelenay S, Sousa CR. NK cells stimulate recruitment of cDC1 into the tumor microenvironment promoting cancer immune control. Cell. 2018;172(5):1022–37.

Alfei F, Ho PC, Lo WL. DCision-making in tumors governs T cell antitumor immunity. Oncogene. 2021;40(34):5253–61.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Peng X, He Y, Huang J, Tao Y, Liu S. Metabolism of dendritic cells in tumor microenvironment: for immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:613492.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

McGettrick AF, O’Neill LA. How metabolism generates signals during innate immunity and inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(32):22893–8.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Møller SH, Wang L, Ho PC. Metabolic programming in dendritic cells tailors immune responses and homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(3):370–83.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Wculek SK, Khouili SC, Priego E, Heras-Murillo I, Sancho D. Metabolic control of dendritic cell functions: digesting information. Front Immunol. 2019;10:775.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Naldini A, Morena E, Pucci A, Miglietta D, Riboldi E, Sozzani S, et al. Hypoxia affects dendritic cell survival: role of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and lipopolysaccharide. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(2):587–95.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Carraro F, Pucci A, Pellegrini M, Giuseppe Pelicci P, Baldari CT, Naldini A. p66Shc is involved in promoting HIF-1α accumulation and cell death in hypoxic T cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211(2):439–47.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Mortezaee K, Majidpoor J. The impact of hypoxia on immune state in cancer. Life Sci. 2021;286:120057.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Márquez S, Fernández JJ, Terán-Cabanillas E, Herrero C, Alonso S, Azogil A, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1α enhances IL-23 expression by human dendritic cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:639.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Hackstein H, Taner T, Zahorchak AF, Morelli AE, Logar AJ, Gessner A, et al. Rapamycin inhibits IL-4—induced dendritic cell maturation in vitro and dendritic cell mobilization and function in vivo. Blood. 2003;101(11):4457–63.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Cao W, Manicassamy S, Tang H, Kasturi SP, Pirani A, Murthy N, et al. Toll-like receptor–mediated induction of type I interferon in plasmacytoid dendritic cells requires the rapamycin-sensitive PI (3) K-mTOR-p70S6K pathway. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(10):1157–64.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Turnquist HR, Raimondi G, Zahorchak AF, Fischer RT, Wang Z, Thomson AW. Rapamycin-conditioned dendritic cells are poor stimulators of allogeneic CD4+ T cells, but enrich for antigen-specific Foxp3+ T regulatory cells and promote organ transplant tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):7018–31.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Herber DL, Cao W, Nefedova Y, Novitskiy SV, Nagaraj S, Tyurin VA, et al. Lipid accumulation and dendritic cell dysfunction in cancer. Nat Med. 2010;16(8):880–6.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Lu H, Forbes RA, Verma A. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation by aerobic glycolysis implicates the Warburg effect in carcinogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(26):23111–5.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Carstensen LS, Lie-Andersen O, Obers A, Crowther MD, Svane IM, Hansen M. Long-term exposure to inflammation induces differential cytokine patterns and apoptosis in dendritic cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2702.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Hansen M, Andersen MH. The role of dendritic cells in cancer. InSeminars Immunopathol. 2017;39:307–16.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Jin HR, Wang J, Wang ZJ, Xi MJ, Xia BH, Deng K, et al. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment: from mechanisms to therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16(1):103.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Giovanelli P, Sandoval TA, Cubillos-Ruiz JR. Dendritic cell metabolism and function in tumors. Trends Immunol. 2019;40(8):699–718.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Veglia F, Tyurin VA, Mohammadyani D, Blasi M, Duperret EK, Donthireddy L, et al. Lipid bodies containing oxidatively truncated lipids block antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells in cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):2122.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Caronni N, Simoncello F, Stafetta F, Guarnaccia C, Ruiz-Moreno JS, Opitz B, et al. Downregulation of membrane trafficking proteins and lactate conditioning determine loss of dendritic cell function in lung cancer. Can Res. 2018;78(7):1685–99.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Silberman PC, Rutkowski MR, Chopra S, Perales-Puchalt A, Song M, et al. ER stress sensor XBP1 controls antitumor immunity by disrupting dendritic cell homeostasis. Cell. 2015;161(7):1527–38.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Song M, Cubillos-Ruiz JR. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in intratumoral immune cells: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2019;40(2):128–41.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Zhu C, Dixon KO, Newcomer K, Gu G, Xiao S, Zaghouani S, Schramm MA, Wang C, Zhang H, Goto K, Christian E. Tim-3 adaptor protein Bat3 is a molecular checkpoint of T cell terminal differentiation and exhaustion. Sci Adv. 2021;7(18):eabd2710.

Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Bettigole SE, Glimcher LH. Tumorigenic and immunosuppressive effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress in cancer. Cell. 2017;168(4):692–706.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Werfel TA, Cook RS. Efferocytosis in the tumor microenvironment. InSeminars in immunopathology. 2018;40(6).

Gottfried E, Kunz-Schughart LA, Ebner S, Mueller-Klieser W, Hoves S, Andreesen R, et al. Tumor-derived lactic acid modulates dendritic cell activation and antigen expression. Blood. 2006;107(5):2013–21.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Wobser M, Voigt H, Houben R, Eggert AO, Freiwald M, Kaemmerer U, et al. Dendritic cell based antitumor vaccination: impact of functional indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase expression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1017–24.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Hwang KW, Orabona C, Vacca C, Bianchi R, et al. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(12):1206–12.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Munn DH, Mellor AL. IDO in the tumor microenvironment: inflammation, counter-regulation, and tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(3):193–207.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

McDonnell AM, Robinson BW, Currie AJ. Tumor antigen cross-presentation and the dendritic cell: where it all begins? J Immunol Res. 2010;2010(1):539519.

Article

Google Scholar

Xiao Z, Wang R, Wang X, Yang H, Dong J, He X, et al. Impaired function of dendritic cells within the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;27(14):1213629.

Article

Google Scholar

Wu Y, Pu X, Wang X, Xu M. Reprogramming of lipid metabolism in the tumor microenvironment: a strategy for tumor immunotherapy. Lipids Health Dis. 2024;23(1):35.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

He S, Zheng L, Qi C. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the tumor microenvironment and their targeting in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2025;24(1):5.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Wang H, Zhou F, Qin W, Yang Y, Li X, Liu R. Metabolic regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor immune microenvironment: targets and therapeutic strategies. Theranostics. 2025;15(6):2159.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Grzywa TM, Sosnowska A, Matryba P, Rydzynska Z, Jasinski M, Nowis D, Golab J. Myeloid cell-derived arginase in cancer immune response. Front Immunol. 2020;11:938.

Wang F, Lou J, Gao X, Zhang L, Sun F, Wang Z, et al. Spleen-targeted nanosystems for immunomodulation. Nano Today. 2023;1(52):101943.

Article

Google Scholar

Cao W, Ramakrishnan R, Tuyrin VA, Veglia F, Condamine T, Amoscato A, et al. Oxidized lipids block antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells in cancer. J Immunol. 2014;192(6):2920–31.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Traversari C, Sozzani S, Steffensen KR, Russo V. LXR-dependent and-independent effects of oxysterols on immunity and tumor growth. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(7):1896–903.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Villablanca EJ, Raccosta L, Zhou D, Fontana R, Maggioni D, Negro A, et al. Tumor-mediated liver X receptor-α activation inhibits CC chemokine receptor-7 expression on dendritic cells and dampens antitumor responses. Nat Med. 2010;16(1):98–105.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Bosteels V, Maréchal S, De Nolf C, Rennen S, Maelfait J, Tavernier SJ, Vetters J, Van De Velde E, Fayazpour F, Deswarte K, Lamoot A. LXR signaling controls homeostatic dendritic cell maturation. Sci Immunol. 2023;8(83):eadd3955.

Shen M, Jiang X, Peng Q, Oyang L, Ren Z, Wang J, et al. The cGAS-STING pathway in cancer immunity: mechanisms, challenges, and therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol. 2025;18(1):40.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Obeid M, Ortiz C, Criollo A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4–dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13(9):1050–9.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Yanai H, Ban T, Wang Z, Choi MK, Kawamura T, Negishi H, et al. HMGB proteins function as universal sentinels for nucleic-acid-mediated innate immune responses. Nature. 2009;462(7269):99–103.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Chiba S, Baghdadi M, Akiba H, Yoshiyama H, Kinoshita I, Dosaka-Akita H, et al. Tumor-infiltrating DCs suppress nucleic acid–mediated innate immune responses through interactions between the receptor TIM-3 and the alarmin HMGB1. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(9):832–42.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Xu MM, Pu Y, Han D, Shi Y, Cao X, Liang H, et al. Dendritic cells but not macrophages sense tumor mitochondrial DNA for cross-priming through signal regulatory protein α signaling. Immunity. 2017;47(2):363–73.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Huang CY, Ye ZH, Huang MY, Lu JJ. Regulation of CD47 expression in cancer cells. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(12):100862.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Sockolosky JT, Dougan M, Ingram JR, Ho CC, Kauke MJ, Almo SC, et al. Durable antitumor responses to CD47 blockade require adaptive immune stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(19):E2646–54.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Ng II, Zhang Z, Xiao K, Ye M, Tian T, Zhu Y, He Y, Chu L, Tang H. Targeting WEE1 in tumor-associated dendritic cells potentiates antitumor immunity via the cGAS/STING pathway. Cell Reports. 2025;44(6).

Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. 2009;461(7265):788–92.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Fu J, Kanne DB, Leong M, Glickman LH, McWhirter SM, Lemmens E, Mechette K, Leong JJ, Lauer P, Liu W, Sivick KE. STING agonist formulated cancer vaccines can cure established tumors resistant to PD-1 blockade. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(283):283ra52.

Motedayen Aval L, Pease JE, Sharma R, Pinato DJ. Challenges and opportunities in the clinical development of STING agonists for cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10):3323.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Spranger S, Dai D, Horton B, Gajewski TF. Tumor-residing Batf3 dendritic cells are required for effector T cell trafficking and adoptive T cell therapy. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(5):711–23.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signaling prevents anti-tumor immunity. Nature. 2015;523(7559):231–5.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Barry KC, Hsu J, Broz ML, Cueto FJ, Binnewies M, Combes AJ, et al. A natural killer–dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy–responsive tumor microenvironments. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1178–91.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

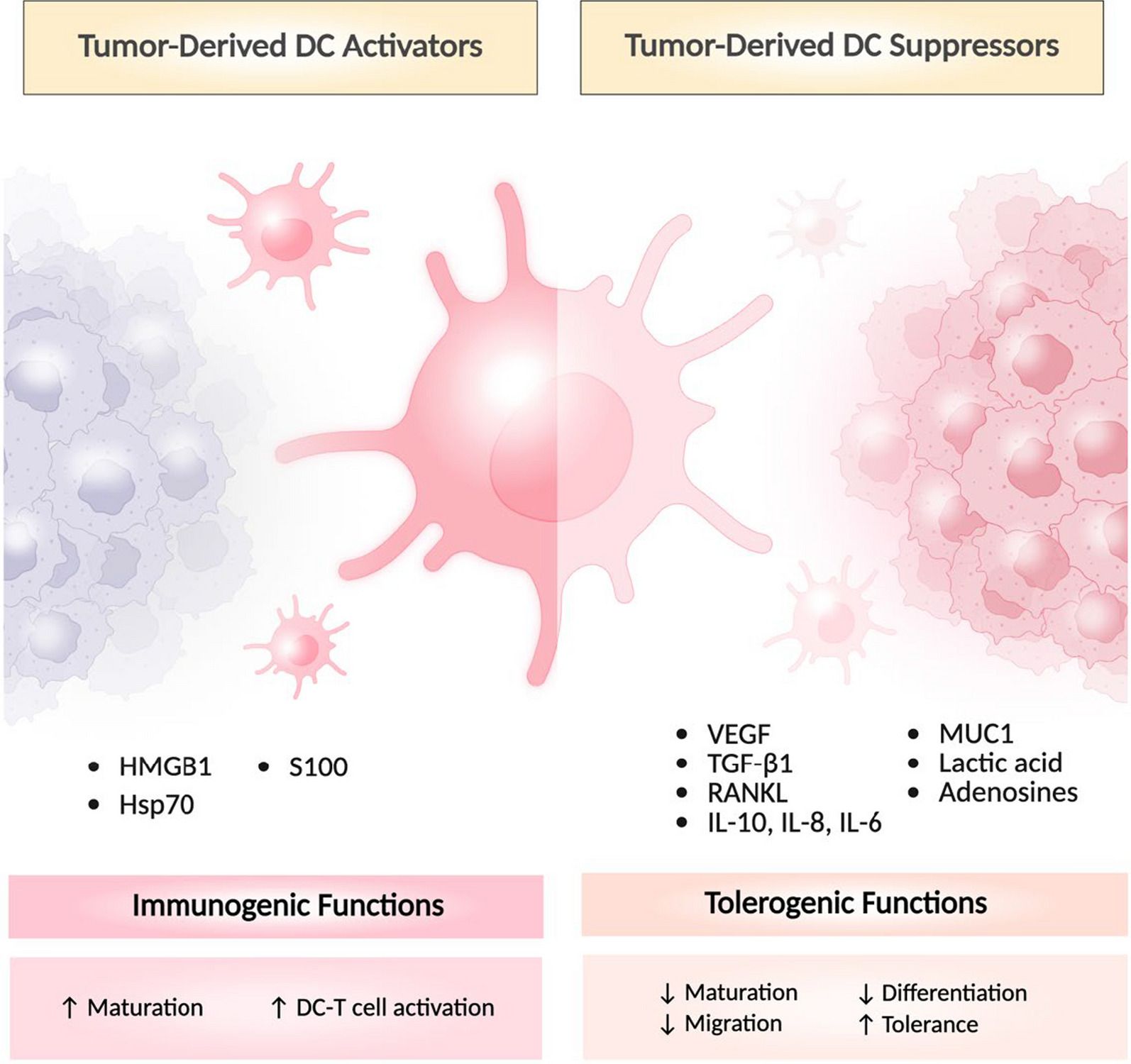

Zong J, Keskinov AA, Shurin GV, Shurin MR. Tumor-derived factors modulating dendritic cell function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:821–33.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Zelenay S, Van Der Veen AG, Böttcher JP, Snelgrove KJ, Rogers N, Acton SE, et al. Cyclooxygenase-dependent tumor growth through evasion of immunity. Cell. 2015;162(6):1257–70.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Tang M, Diao J, Gu H, Khatri I, Zhao J, Cattral MS. Toll-like receptor 2 activation promotes tumor dendritic cell dysfunction by regulating IL-6 and IL-10 receptor signaling. Cell Rep. 2015;13(12):2851–64.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Nirschl CJ, Suárez-Fariñas M, Izar B, Prakadan S, Dannenfelser R, Tirosh I, et al. IFNγ-dependent tissue-immune homeostasis is co-opted in the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2017;170(1):127–41.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Fu C, Liang X, Cui W, Ober-Blöbaum JL, Vazzana J, Shrikant PA, et al. β-Catenin in dendritic cells exerts opposite functions in cross-priming and maintenance of CD8+ T cells through regulation of IL-10. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(9):2823–8.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Ramalingam R. Importance of TGF-beta signaling in dendritic cells to maintain immune tolerance. 2012; Doctoral dissertation, The University of Arizona.

Flavell RA, Sanjabi S, Wrzesinski SH, Licona-Limón P. The polarization of immune cells in the tumor environment by TGFβ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(8):554–67.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Hsu JM, Li CW, Lai YJ, Hung MC. Posttranslational modifications of PD-L1 and their applications in cancer therapy. Can Res. 2018;78(22):6349–53.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Zhang L, Nishi H. Transcriptome analysis of Homo sapiens and Mus musculus reveals mechanisms of CD8+ T cell exhaustion caused by different factors. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0274494.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Kagoya Y. Molecular profiles of exhausted T cells and their impact on response to immune checkpoint blockade. Gan to kagaku ryoho. Cancer Chemother. 2022;49(6):609–14.

Verdon DJ, Mulazzani M, Jenkins MR. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of CD8+ T cell differentiation, dysfunction and exhaustion. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(19):7357.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Mende I, Engleman EG. Breaking self-tolerance to tumor-associated antigens by in vivo manipulation of dendritic cells. InImmunological Tolerance Methods Protocols. 2007;457–468. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.

Mende I, Engleman EG. Breaking tolerance to tumors with dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1058(1):96–104.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Gehrcken L, Deben C, Smits E, Van Audenaerde JR. STING agonists and how to reach their full potential in cancer immunotherapy. Adv Sci. 2025;12(17):2500296.

Article

Google Scholar

Pavlovic K, Tristán-Manzano M, Maldonado-Pérez N, Cortijo-Gutierrez M, Sánchez-Hernández S, Justicia-Lirio P, et al. Using gene editing approaches to fine-tune the immune system. Front Immunol. 2020;11:570672.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Xu Y, Chen C, Guo Y, Hu S, Sun Z. Effect of CRISPR/Cas9-edited PD-1/PD-L1 on tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:848327.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Allemailem KS, Alsahli MA, Almatroudi A, Alrumaihi F, Al Abdulmonem W, Moawad AA, Alwanian WM, Almansour NM, Rahmani AH, Khan AA. Innovative strategies of reprogramming immune system cells by targeting CRISPR/Cas9-based genome-editing tools: a new era of cancer management. Int J Nanomed. 2023; 5531–59.

Becker AM. Exploring the modulation and development of type 3 dendritic cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Sl:Sn; 2023.

Turnis ME, Rooney CM. Enhancement of dendritic cells as vaccines for cancer. Immunotherapy. 2010;2(6):847–62.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Cornel AM, Van Til NP, Boelens JJ, Nierkens S. Strategies to genetically modulate dendritic cells to potentiate antitumor responses in hematologic malignancies. Front Immunol. 2018;9:982.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Caux C, Massacrier C, Vanbervliet B, Dubois B, Durand I, Cella M, Lanzavecchia A, Banchereau J. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors from human cord blood differentiate along two independent dendritic cell pathways in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus tumor necrosis factor α: II. Functional analysis. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 1997;90(4):1458–70.

Kumar J, Kale V, Limaye L. Umbilical cord blood-derived CD11c+ dendritic cells could serve as an alternative allogeneic source of dendritic cells for cancer immunotherapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:1–5.

Article

Google Scholar

Kikuchi T. Genetically modified dendritic cells for therapeutic immunity. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;208(1):1–8.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Rossi A, Dupaty L, Aillot L, Zhang L, Gallien C, Hallek M, et al. Vector uncoating limits adeno-associated viral vector-mediated transduction of human dendritic cells and vector immunogenicity. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3631.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Jost M, Jacobson AN, Hussmann JA, Cirolia G, Fischbach MA, Weissman JS. CRISPR-based functional genomics in human dendritic cells. Elife. 2021;10:e65856.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Hutten T, Thordardottir S, Hobo W, Hübel J, van der Waart AB, Cany J, et al. Ex vivo generation of interstitial and langerhans cell-like dendritic cell subset–based vaccines for hematological malignancies. J Immunother. 2014;37(5):267–77.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Gundry MC, Brunetti L, Lin A, Mayle AE, Kitano A, Wagner D, et al. Highly efficient genome editing of murine and human hematopoietic progenitor cells by CRISPR/Cas9. Cell Rep. 2016;17(5):1453–61.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Mao K, Tan H, Cong X, Liu J, Xin Y, Wang J, et al. Optimized lipid nanoparticles enable effective CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in dendritic cells for enhanced immunotherapy. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2025;15(1):642–56.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Hung KL, Meitlis I, Hale M, Chen CY, Singh S, Jackson SW, et al. Engineering protein-secreting plasma cells by homology-directed repair in primary human B cells. Mol Ther. 2018;26(2):456–67.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Okada N, Mori N, Koretomo R, Okada Y, Nakayama T, Yoshie O, et al. Augmentation of the migratory ability of DC-based vaccine into regional lymph nodes by efficient CCR7 gene transduction. Gene Ther. 2005;12(2):129–39.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Alvarez D, Vollmann EH, von Andrian UH. Mechanisms and consequences of dendritic cell migration. Immunity. 2008;29(3):325–42.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Jiang A, Bloom O, Ono S, Cui W, Unternaehrer J, Jiang S, et al. Disruption of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion induces a functionally distinct pathway of dendritic cell maturation. Immunity. 2007;27(4):610–24.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Bonehill A, Tuyaerts S, Van Nuffel AM, Heirman C, Bos TJ, Fostier K, et al. Enhancing the T-cell stimulatory capacity of human dendritic cells by co-electroporation with CD40L, CD70 and constitutively active TLR4 encoding mRNA. Mol Ther. 2008;16(6):1170–80.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Grünebach F, Kayser K, Weck MM, Müller MR, Appel S, Brossart P. Cotransfection of dendritic cells with RNA coding for HER-2/neu and 4–1BBL increases the induction of tumor antigen specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12(9):749–56.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

De Keersmaecker B, Heirman C, Corthals J, Empsen C, van Grunsven LA, Allard SD, et al. The combination of 4–1BBL and CD40L strongly enhances the capacity of dendritic cells to stimulate HIV-specific T cell responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(6):989–99.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Boczkowski D, Lee J, Pruitt S, Nair S. Dendritic cells engineered to secrete anti-GITR antibodies are effective adjuvants to dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16(12):900–11.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Han D, Liu J, Chen C, Dong L, Liu Y, Chang R, et al. Anti-tumor immunity controlled through mRNA m6A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature. 2019;566(7743):270–4.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(1):3–13.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Theisen DJ, Davidson JT IV, Briseño CG, Gargaro M, Lauron EJ, Wang Q, et al. WDFY4 is required for cross-presentation in response to viral and tumor antigens. Science. 2018;362(6415):694–9.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Parnas O, Jovanovic M, Eisenhaure TM, Herbst RH, Dixit A, Ye CJ, et al. A genome-wide CRISPR screen in primary immune cells to dissect regulatory networks. Cell. 2015;162(3):675–86.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Albrecht V, Hofer TP, Foxwell B, Frankenberger M, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. Tolerance induced via TLR2 and TLR4 in human dendritic cells: role of IRAK-1. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:1–4.

Article

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, Shen S, Zhao G, Xu CF, Zhang HB, Luo YL, et al. In situ repurposing of dendritic cells with CRISPR/Cas9-based nanomedicine to induce transplant tolerance. Biomaterials. 2019;217:119302.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, Maeder ML, Reyon D, Joung JK, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):822–6.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Tsai SQ, Nguyen N, Zheng Z, Joung JK. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 variants with undetectable genome-wide off-targets. Nature. 2016;529(7587):490–5.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Xu H, Look T, Prithiviraj S, Lennartz D, Cáceres MD, Götz K, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing in conditionally immortalized HoxB8 cells for studying gene regulation in mouse dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2022;52(11):1859–62.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

He M, Roussak K, Ma F, Borcherding N, Garin V, White M, Schutt C, Jensen TI, Zhao Y, Iberg CA, Shah K. CD5 expression by dendritic cells directs T cell immunity and sustains immunotherapy responses. Science. 2023;379(6633):eabg2752.

Groom JR. Regulators of T-cell fate: integration of cell migration, differentiation and function. Immunol Rev. 2019;289(1):101–14.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Kwon YW, Ahn HS, Lee JW, Yang HM, Cho HJ, Kim SJ, et al. HLA DR genome editing with TALENs in human iPSCs produced immune-tolerant dendritic cells. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021(1):8873383.

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Menger L, Sledzinska A, Bergerhoff K, Vargas FA, Smith J, Poirot L, et al. TALEN-mediated inactivation of PD-1 in tumor-reactive lymphocytes promotes intratumoral T-cell persistence and rejection of established tumors. Can Res. 2016;76(8):2087–93.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Bhardwaj A, Nain V. TALENs—an indispensable tool in the era of CRISPR: a mini review. J Genetic Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19(1):125.

Article

Google Scholar

Hashimoto M, Bacman SR, Peralta S, Falk MJ, Chomyn A, Chan DC, et al. MitoTALEN: a general approach to reduce mutant mtDNA loads and restore oxidative phosphorylation function in mitochondrial diseases. Mol Ther. 2015;23(10):1592–9.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Hivroz C, Chemin K, Tourret M, Bohineust A. Crosstalk between T lymphocytes and dendritic cells. Crit Reviews™ Immunol. 2012;32(2).

Rittiner JE, Moncalvo M, Chiba-Falek O, Kantor B. Gene-editing technologies paired with viral vectors for translational research into neurodegenerative diseases. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;12(13):148.

Article

Google Scholar

Mahfouz MM, Piatek A, Stewart CN Jr. Genome engineering via TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 systems: challenges and perspectives. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;12(8):1006–14.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Tenjo-Castaño F, Montoya G, Carabias A. Transposons and CRISPR: rewiring gene editing. Biochemistry. 2022;62(24):3521–32.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Hanlon KS, Kleinstiver BP, Garcia SP, Zaborowski MP, Volak A, Spirig SE, et al. High levels of AAV vector integration into CRISPR-induced DNA breaks. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4439.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Nelson CE, Wu Y, Gemberling MP, Oliver ML, Waller MA, Bohning JD, et al. Long-term evaluation of AAV-CRISPR genome editing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):427–32.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Nerys-Junior A, Braga-Dias LP, Pezzuto P, Cotta-de-Almeida V, Tanuri A. Comparison of the editing patterns and editing efficiencies of TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 when targeting the human CCR5 gene. Genet Mol Biol. 2018;19(41):167–79.

Article

Google Scholar

Miro F, Nobile C, Blanchard N, Lind M, Filipe-Santos O, Fieschi C, et al. T cell-dependent activation of dendritic cells requires IL-12 and IFN-γ signaling in T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177(6):3625–34.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Gupta YH, Khanom A, Acton SE. Control of dendritic cell function within the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:733800.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Tenbusch M, Kuate S, Tippler B, Gerlach N, Schimmer S, Dittmer U, et al. Coexpression of GM-CSF and antigen in DNA prime-adenoviral vector boost immunization enhances polyfunctional CD8+ T cell responses, whereas expression of GM-CSF antigen fusion protein induces autoimmunity. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:1–5.

Article

Google Scholar

Stam AG, Santegoets SJ, Westers TM, Sombroek CC, Janssen JJ, Tillman BW, et al. CD40-targeted adenoviral GM-CSF gene transfer enhances and prolongs the maturation of human CML-derived dendritic cells upon cytokine deprivation. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(7):1162–5.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Ghasemi A, Martinez-Usatorre A, Li L, Hicham M, Guichard A, Marcone R, et al. Cytokine-armed dendritic cell progenitors for antigen-agnostic cancer immunotherapy. Nature Cancer. 2024;5(2):240–61.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Zhang L, Morgan RA, Beane JD, Zheng Z, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered with an inducible gene encoding interleukin-12 for the immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(10):2278–88.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Nguyen KG, Vrabel MR, Mantooth SM, Hopkins JJ, Wagner ES, Gabaldon TA, et al. Localized interleukin-12 for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:575597.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Kim YS. Tumor therapy applying membrane-bound form of cytokines. Immune network. 2009;9(5):158.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Han J, Wang H. Cytokine-overexpressing dendritic cells for cancer immunotherapy. Exper Mole Med. 2024:1.

Stripecke R. Lentivirus-induced dendritic cells (iDC) for immune-regenerative therapies in cancer and stem cell transplantation. Biomedicines. 2014;2(3):229–46.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Gorodilova AV, Kitaeva KV, Filin IY, Mayasin YP, Kharisova CB, Issa SS, et al. The potential of dendritic cell subsets in the development of personalized immunotherapy for cancer treatment. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45(10):8053–70.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Panya A, Thepmalee C, Sawasdee N, Sujjitjoon J, Phanthaphol N, Junking M, et al. Cytotoxic activity of effector T cells against cholangiocarcinoma is enhanced by self-differentiated monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1579–88.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(1):20–37.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Lu Q, Kou D, Lou S, Ashrafizadeh M, Aref AR, Canadas I, et al. Nanoparticles in tumor microenvironment remodeling and cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17(1):16.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Wang B, Hu S, Teng Y, Chen J, Wang H, Xu Y, et al. Current advance of nanotechnology in diagnosis and treatment for malignant tumors. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):200.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Hu X, Wu T, Bao Y, Zhang Z. Nanotechnology based therapeutic modality to boost antitumor immunity and collapse tumor defense. J Control Release. 2017;256:26–45.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Tran TH, Tran TT, Nguyen HT, Dai Phung C, Jeong JH, Stenzel MH, et al. Nanoparticles for dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Int J Pharm. 2018;542(1–2):253–65.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Sui Y, Berzofsky JA. Trained immunity inducers in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1427443.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Yang D, Liu B, Sha H. Advances and prospects of cell-penetrating peptides in tumor immunotherapy. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):3392.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Abd-Aziz N, Poh CL. Development of peptide-based vaccines for cancer. Journal of Oncology. 2022;2022(1):9749363.

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Srivastava P, Rütter M, Antoniraj G, Ventura Y, David A. dendritic cell-targeted nanoparticles enhance T cell activation and antitumor immune responses by boosting antigen presentation and blocking PD-L1 pathways. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(40):53577–90.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Cao Z, Yang X, Yang W, Chen F, Jiang W, Zhan S, et al. Modulation of dendritic cell function via nanoparticle-induced cytosolic calcium changes. ACS Nano. 2024;18(10):7618–32.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(9):941–51.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Zelepukin IV, Shevchenko KG, Deyev SM. Rediscovery of mononuclear phagocyte system blockade for nanoparticle drug delivery. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4366.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Handa M, Beg S, Shukla R, Barkat MA, Choudhry H, Singh KK. Recent advances in lipid-engineered multifunctional nanophytomedicines for cancer targeting. J Control Release. 2021;340:48–59.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Hajj KA, Whitehead KA. Tools for translation: non-viral materials for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater. 2017;2:10 [Internet]. 2017 Sep 12 [cited 2025 Aug 25];2(10):1–17. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/natrevmats201756

Sabnis S, Kumarasinghe ES, Salerno T, Mihai C, Ketova T, Senn JJ, et al. A Novel Amino Lipid Series for mRNA Delivery: Improved Endosomal Escape and Sustained Pharmacology and Safety in Non-human Primates. Molecular Therapy [Internet]. 2018 Jun 6 [cited 2025 Aug 25];26(6):1509–19. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525001618301187

Miao L, Lin J, Huang Y, Li L, Delcassian D, Ge Y, et al. Synergistic lipid compositions for albumin receptor mediated delivery of mRNA to the liver. Nature Commun. 2020;11:1 [Internet]. 2020 May 15 [cited 2025 Aug 25];11(1):1–13. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16248-y

Kauffman KJ, Dorkin JR, Yang JH, Heartlein MW, Derosa F, Mir FF, et al. Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for mRNA Delivery in Vivo with Fractional Factorial and Definitive Screening Designs. Nano Lett [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 25];15(11):7300–6. Available from: /doi/pdf/https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02497

Liu H, Moynihan KD, Zheng Y, Szeto GL, Li AV, Huang B, et al. Structure-based programming of lymph-node targeting in molecular vaccines. Nature. 2014;507(7493):519–22.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Gbian DL, Omri A. Lipid-based drug delivery systems for diseases managements. Biomedicines. 2022;10(9):2137.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Ndeupen S, Qin Z, Jacobsen S, Bouteau A, Estanbouli H, Igyártó BZ. The mRNA-LNP platform’s lipid nanoparticle component used in preclinical vaccine studies is highly inflammatory. Iscience. 2021;24(12).

Alameh MG, Tombácz I, Bettini E, Lederer K, Ndeupen S, Sittplangkoon C, et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity. 2021;54(12):2877–92.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Miao L, Li L, Huang Y, Delcassian D, Chahal J, Han J, et al. Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases antitumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(10):1174–85.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Connors J, Joyner D, Mege NJ, Cusimano GM, Bell MR, Marcy J, et al. Lipid nanoparticles (LNP) induce activation and maturation of antigen presenting cells in young and aged individuals. Communications biology. 2023;6(1):188.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Zhang M, Wang Y, Li B, Yang B, Zhao M, Li B, Liu J, Hu Y, Wu Z, Ong Y, Han X. STING‐activating polymers boost lymphatic delivery of mRNA vaccine to potentiate cancer immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2025:2412654.

Nguyen NT, Le XT, Lee WT, Lim YT, Oh KT, Lee ES, et al. STING-activating dendritic cell-targeted nanovaccines that evoke potent antigen cross-presentation for cancer immunotherapy. Bioactive Mater. 2024;42:345–65.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Chin EN, Yu C, Vartabedian VF, Jia Y, Kumar M, Gamo AM, et al. Antitumor activity of a systemic STING-activating non-nucleotide cGAMP mimetic. Science. 2020;369(6506):993–9.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Wang Y, Li S, Hu M, Yang Y, McCabe E, Zhang L, et al. Universal STING mimic boosts antitumor immunity via preferential activation of tumor control signaling pathways. Nat Nanotechnol. 2024;19(6):856–66.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Nagy NA, De Haas AM, Geijtenbeek TB, Van Ree R, Tas SW, Van Kooyk Y, et al. Therapeutic liposomal vaccines for dendritic cell activation or tolerance. Front Immunol. 2021;12:674048.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Li S, Luo M, Wang Z, Feng Q, Wilhelm J, Wang X, et al. Prolonged activation of innate immune pathways by a polyvalent STING agonist. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5(5):455–66.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Corrales L, Glickman LH, McWhirter SM, Kanne DB, Sivick KE, Katibah GE, et al. Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. Cell Rep. 2015;11(7):1018–30.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Hong C, Schubert M, Tijhuis AE, Requesens M, Roorda M, van den Brink A, et al. cGAS–STING drives the IL-6-dependent survival of chromosomally instable cancers. Nature. 2022;607(7918):366–73.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Zhang C, Shang G, Gui X, Zhang X, Bai XC, Chen ZJ. Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature. 2019;567(7748):394–8.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

He Y, Hong C, Yan EZ, Fletcher SJ, Zhu G, Yang M, Li Y, Sun X, Irvine DJ, Li J, Hammond PT. Self-assembled cGAMP-STINGΔTM signaling complex as a bioinspired platform for cGAMP delivery. Sci Adv. 2020;6(24):eaba7589.

Tse SW, McKinney K, Walker W, Nguyen M, Iacovelli J, Small C, et al. mRNA-encoded, constitutively active STINGV155M is a potent genetic adjuvant of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response. Mol Ther. 2021;29(7):2227–38.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Shumilina E, Huber SM, Lang F. Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of dendritic cell functions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300(6):C1205–14.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Salter RD, Watkins SC. Dendritic cell altered states: what role for calcium? Immunol Rev. 2009;231(1):278–88.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Santegoets SJ, van den Eertwegh AJ, van de Loosdrecht AA, Scheper RJ, de Gruijl TD. Human dendritic cell line models for DC differentiation and clinical DC vaccination studies. J Leucocyte Biol. 2008;84(6):1364–73.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Cardoso A, Minutti CM, Pereira da Costa M, Reis e Sousa C. Dendritic cells revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39(1):131–66.

Herbst C, Harshyne LA, Igyártó BZ. Intracellular monitoring by dendritic cells–a new way to stay informed–from a simple scavenger to an active gatherer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1053582.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Sun X, Zhang Y, Li J, Park KS, Han K, Zhou X, et al. Amplifying STING activation by cyclic dinucleotide–manganese particles for local and systemic cancer metalloimmunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2021;16(11):1260–70.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Grippin A, Sayour E, Wummer B, Monsalve A, Wildes T, Dyson K, Mitchell DA. mRNA-nanoparticles to enhance and track dendritic cell migration. 2018;72.

Huang L, Liu Z, Wu C, Lin J, Liu N. Magnetic nanoparticles enhance the cellular immune response of dendritic cell tumor vaccines by realizing the cytoplasmic delivery of tumor antigens. Bioeng Transl Med. 2023;8(2):e10400.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Lv M, Chen M, Zhang R, Zhang W, Wang C, Zhang Y, et al. Manganese is critical for antitumor immune responses via cGAS-STING and improves the efficacy of clinical immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2020;30(11):966–79.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Wang S, Ni D, Yue H, Luo N, Xi X, Wang Y, et al. Exploration of antigen induced CaCO3 nanoparticles for therapeutic vaccine. Small. 2018;14(14):1704272.

Article

Google Scholar

Hu YX, Han XS, Jing Q. Ca (2+) ion and autophagy. Autophagy Biol Diseases Basic Sci. 2019;28:151–66.

Wang D, Rayani S, Marshall JL. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a vaccine target. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7(7):987–93.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Zhuang X, Wu T, Zhao Y, Hu X, Bao Y, Guo Y, et al. Lipid-enveloped zinc phosphate hybrid nanoparticles for codelivery of H-2Kb and H-2Db-restricted antigenic peptides and monophosphoryl lipid A to induce antitumor immunity against melanoma. J Control Release. 2016;228:26–37.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Heng BC, Zhao X, Tan EC, Khamis N, Assodani A, Xiong S, et al. Evaluation of the cytotoxic and inflammatory potential of differentially shaped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Arch Toxicol. 2011;85:1517–28.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Shi C, Jian C, Wang L, Gao C, Yang T, Fu Z, et al. Dendritic cell hybrid nanovaccine for mild heat inspired cancer immunotherapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):347.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Lee SB, Ahn SB, Lee SW, Jeong SY, Ghilsuk Y, Ahn BC, Kim EM, Jeong HJ, Lee J, Lim DK, Jeon YH. Radionuclide-embedded gold nanoparticles for enhanced dendritic cell-based cancer immunotherapy, sensitive and quantitative tracking of dendritic cells with PET and Cerenkov luminescence. NPG Asia Mater. 2016;8(6):e281.

Lee IH, Kwon HK, An S, Kim D, Kim S, Yu MK, et al. Imageable antigen-presenting gold nanoparticle vaccines for effective cancer immunotherapy in vivo. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2012;51(35):8800.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Kang S, Ahn S, Lee J, Kim JY, Choi M, Gujrati V, et al. Effects of gold nanoparticle-based vaccine size on lymph node delivery and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. J Control Release. 2017;256:56–67.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Fernández TD, Pearson JR, Leal MP, Torres MJ, Blanca M, Mayorga C, et al. Intracellular accumulation and immunological properties of fluorescent gold nanoclusters in human dendritic cells. Biomaterials. 2015;43:1–2.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Le Guével X, Perez Perrino M, Fernández TD, Palomares F, Torres MJ, Blanca M, et al. Multivalent glycosylation of fluorescent gold nanoclusters promotes increased human dendritic cell targeting via multiple endocytic pathways. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(37):20945–56.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Tomić S, Đokić J, Vasilijić S, Ogrinc N, Rudolf R, Pelicon P, et al. Size-dependent effects of gold nanoparticles uptake on maturation and antitumor functions of human dendritic cells in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e96584.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Affandi AJ, Grabowska J, Olesek K, Lopez Venegas M, Barbaria A, Rodríguez E, et al. Selective tumor antigen vaccine delivery to human CD169+ antigen-presenting cells using ganglioside-liposomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(44):27528–39.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Rosalia RA, Cruz LJ, van Duikeren S, Tromp AT, Silva AL, Jiskoot W, et al. CD40-targeted dendritic cell delivery of PLGA-nanoparticle vaccines induce potent antitumor responses. Biomaterials. 2015;40:88–97.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Fransen MF, Sluijter M, Morreau H, Arens R, Melief CJ. Local activation of CD8 T cells and systemic tumor eradication without toxicity via slow release and local delivery of agonistic CD40 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(8):2270–80.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Rueda F, Eich C, Cordobilla B, Domingo P, Acosta G, Albericio F, et al. Effect of TLR ligands co-encapsulated with multiepitopic antigen in nanoliposomes targeted to human DCs via Fc receptor for cancer vaccines. Immunobiology. 2017;222(11):989–97.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Suzuki R, Utoguchi N, Kawamura K, Kadowaki N, Okada N, Takizawa T, Uchiyama T, Maruyama K. Development of effective antigen delivery carrier to dendritic cells via Fc receptor in cancer immunotherapy. Yakugaku Zasshi: J Pharmaceutical Soc Japan. 127(2):301–6.

Hossain MK, Vartak A, Sucheck S, Wall KA. Augmenting vaccine immunogenicity through the use of natural human anti-Rha antibodies and monoclonal Fc domains. J Immunol. 2018;200(1_Supplement):181–4.

Hossain MK, Vartak A, Sucheck SJ, Wall KA. Liposomal fc domain conjugated to a cancer vaccine enhances both humoral and cellular immunity. ACS Omega. 2019;4(3):5204–8.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Lahoud MH, Ahmet F, Zhang JG, Meuter S, Policheni AN, Kitsoulis S, et al. DEC-205 is a cell surface receptor for CpG oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(40):16270–5.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Saluja SS, Hanlon DJ, Sharp FA, Hong E, Khalil D, Robinson E, Tigelaar R, Fahmy TM, Edelson RL. Targeting human dendritic cells via DEC-205 using PLGA nanoparticles leads to enhanced cross-presentation of a melanoma-associated antigen. Int J Nanomed. 2014:5231–46.

Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, et al. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315(5808):107–11.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Neubert K, Lehmann CH, Heger L, Baranska A, Staedtler AM, Buchholz VR, et al. Antigen delivery to CD11c+ CD8− dendritic cells induces protective immune responses against experimental melanoma in mice in vivo. J Immunol. 2014;192(12):5830–8.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Luci C, Anjuère F. IFN-λs and BDCA3+/CD8α+ dendritic cells: towards the design of novel vaccine adjuvants? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10(2):159–61.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Tullett KM, Rojas IM, Minoda Y, Tan PS, Zhang JG, Smith C, et al. Targeting CLEC9A delivers antigen to human CD141+ DC for CD4+ and CD8+ T cell recognition. JCI insight. 2016;1(7):e87102.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Sehgal K, Ragheb R, Fahmy TM, Dhodapkar MV, Dhodapkar KM. Nanoparticle-mediated combinatorial targeting of multiple human dendritic cell (DC) subsets leads to enhanced T cell activation via IL-15–dependent DC crosstalk. J Immunol. 2014;193(5):2297–305.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Ghinnagow R, De Meester J, Cruz LJ, Aspord C, Corgnac S, Macho-Fernandez E, et al. Co-delivery of the NKT agonist α-galactosylceramide and tumor antigens to cross-priming dendritic cells breaks tolerance to self-antigens and promotes antitumor responses. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(9):e1339855.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Schetters ST, Kruijssen LJ, Crommentuijn MH, Kalay H, Ochando J, Den Haan JM, et al. Mouse DC-SIGN/CD209a as target for antigen delivery and adaptive immunity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:990.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Stolk DA, De Haas A, Vree J, Duinkerken S, Lübbers J, Van de Ven R, et al. Lipo-based vaccines as an approach to target dendritic cells for induction of T-and iNKT cell responses. Front Immunol. 2020;11:990.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Gargett T, Abbas MN, Rolan P, Price JD, Gosling KM, Ferrante A, et al. Phase I trial of Lipovaxin-MM, a novel dendritic cell-targeted liposomal vaccine for malignant melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1461–72.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Kumar MA, Baba SK, Sadida HQ, Marzooqi SA, Jerobin J, Altemani FH, et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):27.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Lorite P, Domínguez JN, Palomeque T, Torres MI. Extracellular vesicles: advanced tools for disease diagnosis, monitoring, and therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;26(1):189.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Alexander M, Hu R, Runtsch MC, Kagele DA, Mosbruger TL, Tolmachova T, et al. Exosome-delivered microRNAs modulate the inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):7321.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Henao Agudelo JS, Braga TT, Amano MT, Cenedeze MA, Cavinato RA, Peixoto-Santos AR, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived microvesicles regulate an internal pro-inflammatory program in activated macrophages. Front Immunol. 2017;8:881.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Bian X, Xiao YT, Wu T, Yao M, Du L, Ren S, et al. Microvesicles and chemokines in tumor microenvironment: mediators of intercellular communications in tumor progression. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):50.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Patil SM, Sawant SS, Kunda NK. Exosomes as drug delivery systems: a brief overview and progress update. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2020;154:259–69.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Johnson V, Vasu S, Kumar US, Kumar M. Surface-engineered extracellular vesicles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2023;15(10):2838.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Damo M, Wilson DS, Simeoni E, Hubbell JA. TLR-3 stimulation improves antitumor immunity elicited by dendritic cell exosome-based vaccines in a murine model of melanoma. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):17622.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Matsuzaka Y, Yashiro R. Regulation of extracellular vesicle-mediated immune responses against antigen-specific presentation. Vaccines. 2022;10(10):1691.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Horrevorts SK, Stolk DA, van de Ven R, Hulst M, van Het Hof B, Duinkerken S, et al. Glycan-modified apoptotic melanoma-derived extracellular vesicles as antigen source for antitumor vaccination. Cancers. 2019;11(9):1266.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Choi ES, Song J, Kang YY, Mok H. Mannose-modified serum exosomes for the elevated uptake to murine dendritic cells and lymphatic accumulation. Macromol Biosci. 2019;19(7):1900042.

Article

Google Scholar

Yang Q, Li S, Ou H, Zhang Y, Zhu G, Li S, et al. Exosome-based delivery strategies for tumor therapy: an update on modification, loading, and clinical application. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22(1):41.

Article

Google Scholar

Kalkusova K, Taborska P, Stakheev D, Smrz D. The role of miR-155 in antitumor immunity. Cancers. 2022;14(21):5414.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Asadirad A, Hashemi SM, Baghaei K, Ghanbarian H, Mortaz E, Zali MR, et al. Phenotypical and functional evaluation of dendritic cells after exosomal delivery of miRNA-155. Life Sci. 2019;219:152–62.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Katti A, Diaz BJ, Caragine CM, Sanjana NE, Dow LE. CRISPR in cancer biology and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(5):259–79.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Jung IY, Lee J. Unleashing the therapeutic potential of CAR-T cell therapy using gene-editing technologies. Mol Cells. 2018;41(8):717–23.

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Sahin U, Karikó K, Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics—developing a new class of drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2014;13(10):759–80.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Gerlach AM, Steimle A, Krampen L, Wittmann A, Gronbach K, Geisel J, et al. Role of CD40 ligation in dendritic cell semimaturation. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:1–1.

Article

Google Scholar

Ferrer IR, Wagener ME, Song M, Kirk AD, Larsen CP, Ford ML. Antigen-specific induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are generated following CD40/CD154 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(51):20701–6.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Liu J, Chang J, Jiang Y, Meng X, Sun T, Mao L, et al. Fast and efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in vivo enabled by bioreducible lipid and messenger RNA nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2019;31(33):1902575.

Article

Google Scholar

Oh SA, Wu DC, Cheung J, Navarro A, Xiong H, Cubas R, et al. PD-L1 expression by dendritic cells is a key regulator of T-cell immunity in cancer. Nature cancer. 2020;1(7):681–91.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Wan T, Zhong J, Pan Q, Zhou T, Ping Y, Liu X. Exosome-mediated delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes for tissue-specific gene therapy of liver diseases. Sci Adv. 2022;8(37):eabp9435.

Usman WM, Pham TC, Kwok YY, Vu LT, Ma V, Peng B, et al. Efficient RNA drug delivery using red blood cell extracellular vesicles. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2359.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Gupta N, Polkoff K, Qiao L, Cheng K, Piedrahita J. 200 Developing exosomes as a mediator for CRISPR/Cas-9 delivery. Reprod Fertility Dev. 2019;31(1):225.

Abbasi R, Alamdari-Mahd G, Maleki-Kakelar H, Momen-Mesgin R, Ahmadi M, Sharafkhani M, Rezaie J. Recent advances in the application of engineered exosomes from mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine. Euro J Pharmacol. 2025;177236.

Busatto S, Iannotta D, Walker SA, Di Marzio L, Wolfram J. A simple and quick method for loading proteins in extracellular vesicles. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(4):356.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Dubey S, Chen Z, Talis A, Molotkov A, Ali A, Mintz A, Momen-Heravi F. An exosome-based gene delivery platform for cell-specific CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. bioRxiv. 2023;2023–06.

Bahadorani M, Nasiri M, Dellinger K, Aravamudhan S, Zadegan R. Engineering exosomes for therapeutic applications: decoding biogenesis, content modification, and cargo loading strategies. Int J Nanomed. 2024;7137–64.

Ye Y, Zhang X, Xie F, Xu B, Xie P, Yang T, et al. An engineered exosome for delivering sgRNA: Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex and genome editing in recipient cells. Biomater Sci. 2020;8(10):2966–76.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Whitley JA, Kim S, Lou L, Ye C, Alsaidan OA, Sulejmani E, et al. Encapsulating Cas9 into extracellular vesicles by protein myristoylation. J Extracellular Vesicles. 2022;11(4):e12196.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Osteikoetxea X, Silva A, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Salmond N, Shatnyeva O, Stein J, et al. Engineered Cas9 extracellular vesicles as a novel gene editing tool. J Extracellular Vesicles. 2022;11(5):e12225.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Elsharkasy OM, Hegeman CV, Lansweers I, Cotugno OL, de Groot IY, de Wit ZE, Liang X, Garcia-Guerra A, Moorman NJ, Lefferts J, de Voogt WS. A modular strategy for extracellular vesicle-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 delivery through aptamer-based loading and UV-activated cargo release. BioRxiv. 2024;2024–05.

Yao X, Lyu P, Yoo K, Yadav MK, Singh R, Atala A, et al. Engineered extracellular vesicles as versatile ribonucleoprotein delivery vehicles for efficient and safe CRISPR genome editing. J Extracellular Vesicles. 2021;10(5):e12076.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Wang YL, Lee YH, Chou CL, Chang YS, Liu WC, Chiu HW. Oxidative stress and potential effects of metal nanoparticles: a review of biocompatibility and toxicity concerns. Environ Pollution [Internet]. 2024 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Aug 25];346:123617. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749124003312

Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Reviews Drug Discovery 2020 20:2 [Internet]. 2020 Dec 4 [cited 2025 Aug 25];20(2):101–24. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41573-020-0090-8

Pan Y, Zeng F, Luan X, He G, Qin S, Lu Q, et al. Polyamine-depleting hydrogen-bond organic frameworks unleash dendritic cell and T cell vigor for targeted CRISPR/Cas-assisted cancer immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2025;37(13):2411886.

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Lanza G, Gafà R, Maestri I, Santini A, Matteuzzi M, Cavazzini L. Immunohistochemical pattern of MLH1/MSH2 expression is related to clinical and pathological features in colorectal adenocarcinomas with microsatellite instability. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(7):741–9.

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Wylie B, Macri C, Mintern JD, Waithman J. Dendritic cells and cancer: from biology to therapeutic intervention. Cancers. 2019;11(4):521.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Gardner A, Ruffell B. Dendritic cells and cancer immunity. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(12):855–65.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Rosa FF, Pires CF, Kurochkin I, Ferreira AG, Gomes AM, Palma LG, Shaiv K, Solanas L, Azenha C, Papatsenko D, Schulz O. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(30):eaau4292.

Rosa FF, Pires CF, Zimmermannova O, Pereira CF. Direct reprogramming of mouse embryonic fibroblasts to conventional type 1 dendritic cells by enforced expression of transcription factors. Bio-protocol. 2020;10(10):e3619.

Shimosakai R, Khalil IA, Kimura S, Harashima H. mRNA-Loaded lipid nanoparticles targeting immune cells in the spleen for use as cancer vaccines. Pharmaceuticals [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Aug 25];15(8):1017. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/15/8/1017/htm

Luozhong S, Yuan Z, Sarmiento T, Chen Y, Gu W, McCurdy C, et al. Phosphatidylserine lipid nanoparticles promote systemic RNA delivery to secondary lymphoid organs. Nano Lett [Internet]. 2022 Oct 26 [cited 2025 Aug 25];22(20):8304–11. Available from: /doi/pdf/https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c03234

Verma A, Uzun O, Hu Y, Hu Y, Han HS, Watson N, et al. Surface-structure-regulated cell-membrane penetration by monolayer-protected nanoparticles. Nat Mater. 2008;7(7):588–95.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Wang S, Zhu Y, Du S, Zheng Y. Preclinical Advances in LNP-CRISPR therapeutics for solid tumor treatment. Cells. 2024;13(7):568.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Chen G, Abdeen AA, Wang Y, Shahi PK, Robertson S, Xie R, et al. A biodegradable nanocapsule delivers a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for in vivo genome editing. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(10):974–80.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Wei T, Cheng Q, Min YL, Olson EN, Siegwart DJ. Systemic nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins for effective tissue specific genome editing. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3232.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Zuris JA, Thompson DB, Shu Y, Guilinger JP, Bessen JL, Hu JH, et al. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(1):73–80.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Lin MJ, Svensson-Arvelund J, Lubitz GS, Marabelle A, Melero I, Brown BD, et al. Cancer vaccines: the next immunotherapy frontier. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(8):911–26.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Lee YJ, Kim Y, Park SH, Jo JC. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms. Blood Res. 2023;58(S1):S90–5.

Article

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Jeng LB, Liao LY, Shih FY, Teng CF. Dendritic-cell-vaccine-based immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical trials and recent preclinical studies. Cancers. 2022;14(18):4380.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Stevens D, Ingels J, Van Lint S, Vandekerckhove B, Vermaelen K. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy in lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;12(11):620374.

Article

Google Scholar

Najafi S, Mortezaee K. Advances in dendritic cell vaccination therapy of cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;1(164):114954.

Article

Google Scholar

Pittet MJ, Di Pilato M, Garris C, Mempel TR. Dendritic cells as shepherds of T cell immunity in cancer. Immunity. 2023;56(10):2218–30.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Kumar C, Kohli S, Chiliveru S, Jain M, Sharan B. Complete remission of rare adenocarcinoma of the oropharynx with APCEDEN®(dendritic cell-based vaccine): a case report. Clinical Case Reports. 2017;5(10):1692.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Squadrito ML, Cianciaruso C, Hansen SK, De Palma M. EVIR: chimeric receptors that enhance dendritic cell cross-dressing with tumor antigens. Nat Methods. 2018;15(3):183–6.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Hurvitz SA, Timmerman JM. Recombinant, tumor-derived idiotype vaccination for indolent B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: a focus on FavId™. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5(6):841–52.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar

Dahan R, Barnhart BC, Li F, Yamniuk AP, Korman AJ, Ravetch JV. Therapeutic activity of agonistic, human anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies requires selective FcγR engagement. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(6):820–31.

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

CAS

Google Scholar

Salomon R, Rotem H, Katzenelenbogen Y, Weiner A, Cohen Saban N, Feferman T, et al. Bispecific antibodies increase the therapeutic window of CD40 agonists through selective dendritic cell targeting. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(3):287–302.

Article

PubMed

CAS

Google Scholar