Chloe Hughes,West Midlandsand

John Dalziel,BBC CWR

Ekam Dhaliwal

Ekam DhaliwalIn 2022, 19 year-old Ekam Dhaliwal was a football-loving, sports science student at Coventry University.

He had been…

Chloe Hughes,West Midlandsand

John Dalziel,BBC CWR

Ekam Dhaliwal

Ekam DhaliwalIn 2022, 19 year-old Ekam Dhaliwal was a football-loving, sports science student at Coventry University.

He had been…

What are the main challenges in global health this year? We reached out to experts to highlight the priorities that are likely to dominate the agenda, and the topics expected to take centre stage in 2026.

From shifts in global health…

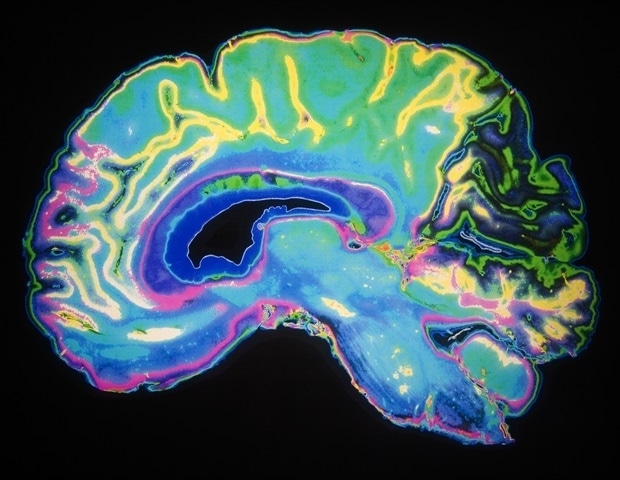

AsianScientist (Jan. 10, 2026) – Clogged drainage pathways in the brain might be a warning for Alzheimer’s disease. These ‘drains’, which surround blood vessels, are filled with cerebrospinal fluid that helps to flush out…

Chawanpaiboon, S. et al. Global, regional, and National estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 7, e37–e46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30451-0 (2019).

On 4 December 2025, the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) issued an alert regarding the possibility of early or more intense activity of respiratory viruses during the 2025-26 season, as compared to previous…

Every time we smile, grimace, or flash a quick look of surprise, it feels effortless, but the brain is quietly coordinating an intricate performance. This study shows that facial gestures aren’t controlled by two separate “systems”…

Does vitamin D and cancer research really support the popular belief that the “sunshine vitamin” prevents malignancy, or is this another wellness myth? According to 2025 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, daily…

Date & Time:

January 19, 2026, at 2 p.m. – 3 p.m.

…

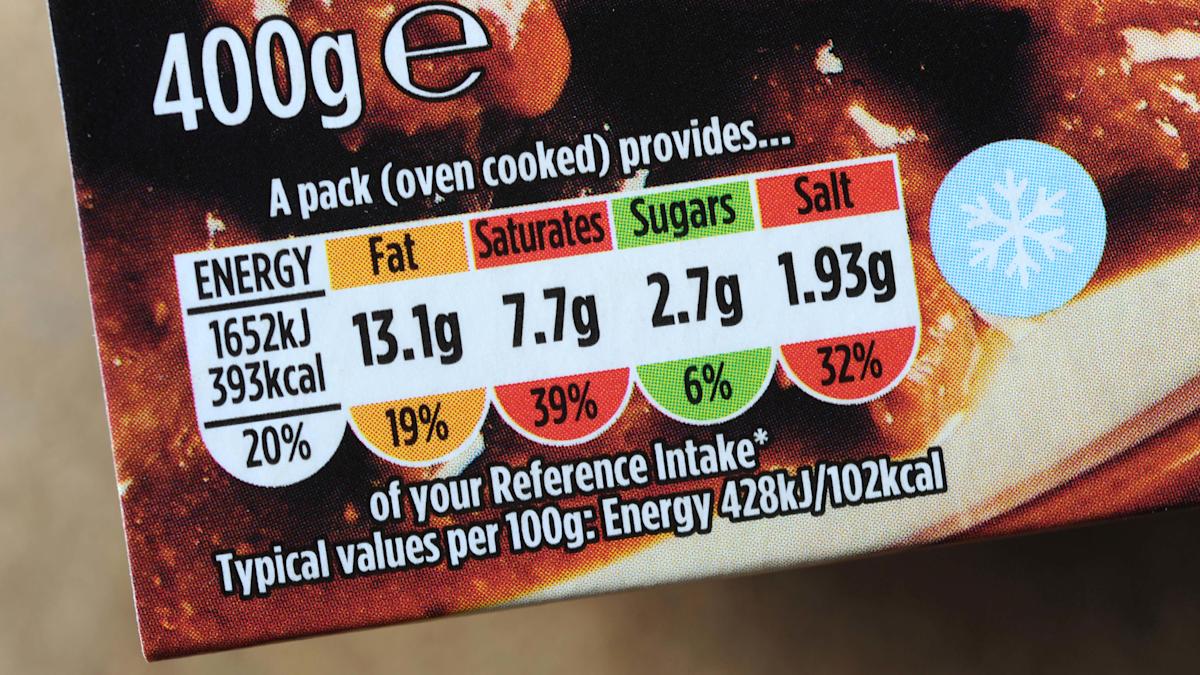

Nutrition labels on the front of food packaging should be made mandatory in the UK, according to a consumer champion.

Which? called on the Government to make the change amid what it described as an “obesity crisis”.

A “better…