Out of five types of exercise, resistance training ranks highest in improving overall brain health. An expert on aging shares how to incorporate lifting into your routine.

(Photo: Ayana Underwood/Canva)

Published January 9, 2026 12:06PM

We know…

Out of five types of exercise, resistance training ranks highest in improving overall brain health. An expert on aging shares how to incorporate lifting into your routine.

(Photo: Ayana Underwood/Canva)

Published January 9, 2026 12:06PM

We know…

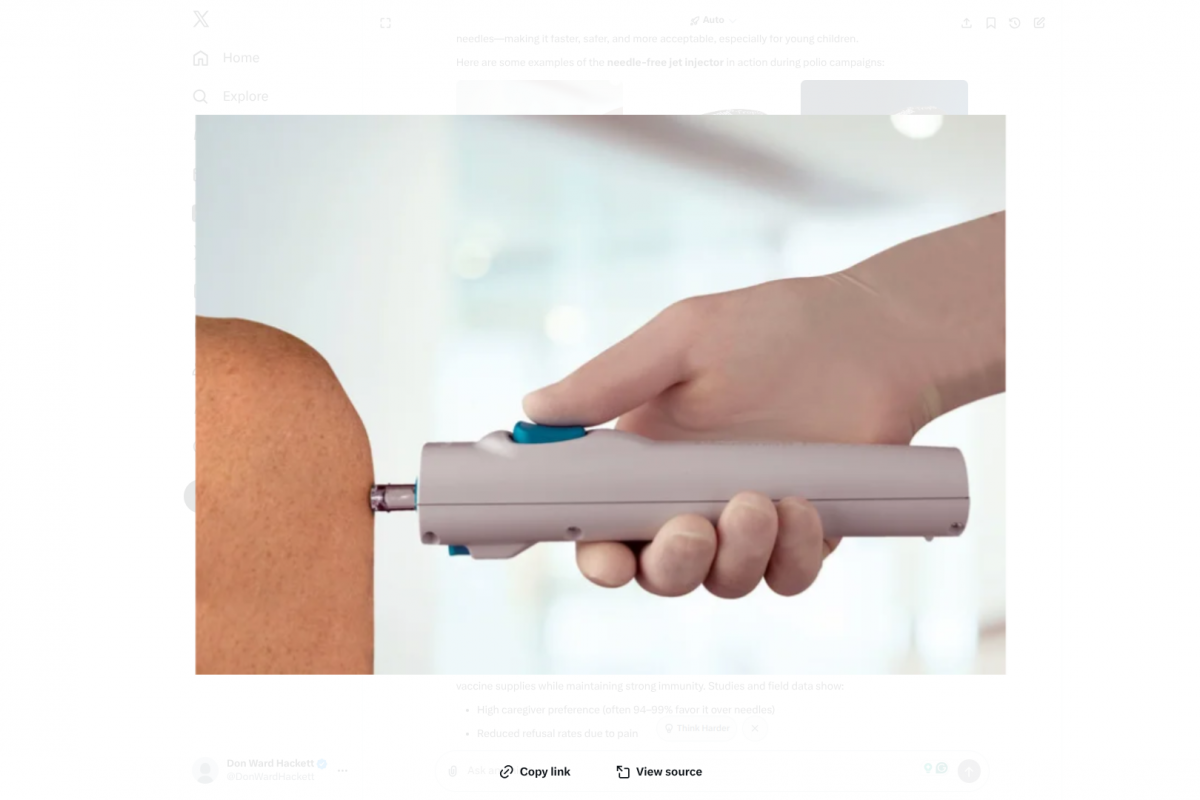

As the global effort to eradicate polio intensifies in 2026, needle-free technology is becoming increasingly popular in the Middle East and surrounding regions.

In a notable advancement for polio eradication in one of the…

The influenza and tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough; Tdap) vaccines are an estimated 69.7% and 88.6% effective against flu- or pertussis-related hospitalizations or emergency department (ED) visits, respectively, among the…

Have you ever felt as though your aching joints or muscles predicted the weather before you could check your app?

You’re not alone. Dr. Christopher Murawski, an orthopedic surgeon with Duke Health, said the concept of weather-related pain has been…

Delivering and adhering to a quality-oriented diet can be beneficial for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) when implemented successfully. In a review published in Nature Reviews Nephrology, authors describe a framework that requires…

Sami Yli-Piipari, associate professor in the Mary Frances Early College of Education’s kinesiology department, spoke with Futurity about the ways that exercise habits (or lack thereof) in adolescence can set the stage for long-term physical…

Every two seconds, someone in the U.S….

Cancer cells employ a variety of strategies to evade the immune system, and modern immunotherapies aim precisely at these escape mechanisms. However, such therapies are not always successful. A research team led by…

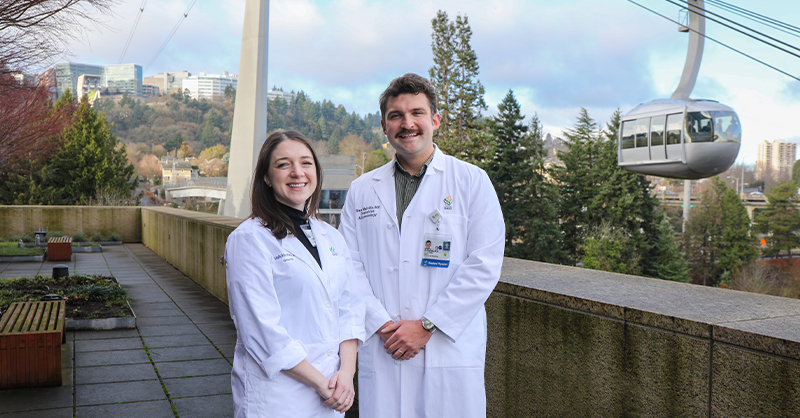

A research team including fertility experts from OHSU’s Center for Women’s Health investigated the health impacts of abortion restrictions on patients who have undergone fertility treatment. (OHSU/Christine Torres Hicks)

Research from…

Scientists at several institutions across the country, in partnership with the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF), have helped generate the largest single-cell immune cell atlas of the bone marrow in patients with multiple myeloma….