In 2025, between epidemiological week (EW) 1 and EW 24, in the Americas Region, 7,132 measles cases have been confirmed, including 13 deaths, in Argentina (n= 34), Belize (n= 34), the Plurinational State of Bolivia (n= 60), Brazil (n= 5), Canada (n= 3,170, including one death),2 Costa Rica (n= 1 case), Mexico (n= 2,597 cases, including nine deaths), Peru (n= 4 cases), and the United States of America (n= 1,227, including three deaths).

According to the information available from confirmed cases, the age group with the highest proportion of cases corresponds to the 10-19 years old group (24%), the 1-4 year old group (22%), and the 20-29 year old group (19%).

Struggle with math? A gentle jolt to the brain might help.

A new study published Tuesday in PLOS Biology suggests that mild electrical stimulation can boost arithmetic performance – and offers fresh insight into the brain mechanisms behind mathematical ability, along with a potential way to optimize learning.

The findings could eventually help narrow cognitive gaps and help build a more intellectually equitable society, the authors argue.

“Different people have different brains, and their brains control a lot in their life,” said Roi Cohen Kadosh, a neuroscientist at the University of Surrey who led the research.

“We think about the environment – if you go to the right school, if you have the right teacher – but it’s also our biology.”

Cohen Kadosh and colleagues recruited 72 University of Oxford students, scanning their brains to measure connectivity between three key regions.

Related: Chewing Wood Could Give Your Brain an Unexpected Boost

Participants then tackled math problems that required either calculating answers or recalling memorized solutions.

They found that stronger connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which governs executive function, and the posterior parietal cortex, involved in memory, predicted better calculation performance.

When the researchers applied a painless form of brain stimulation using electrode-fitted caps – a technique known as transcranial random noise stimulation – the low performers saw their scores jump by 25–29 percent.

The team believes the stimulation works by enhancing the excitability of neurons and interacting with GABA, a brain chemical that inhibits excessive activity – effectively compensating for weak neural connectivity in some participants.

In fact, the stimulation helped underperformers reach or even surpass the scores of peers with naturally stronger brain wiring. But those who already performed well saw no benefit.

“Some people struggle with things, and if we can help their brain to fulfill their potential, we open them a lot of opportunities that otherwise would be closed,” said Cohen Kadosh, calling it an “exciting time” for the field of brain stimulation research.

Still, he flagged a key ethical concern: the risk that such technologies could become more available to those with financial means, widening – rather than closing – access gaps.

He also urged the public not to try this at home. “Some people struggle with learning, and if our research proves successful beyond the lab, we could help them fulfil their ambitions and unlock opportunities that might otherwise remain out of reach.”

© Agence France-Presse

The first time Xing Shaoyun reached for a leprosy patient”s disfigured hand, the patient flinched. “Don’t touch me,” she whispered. “I don’t want to make you sick.”

That moment shattered Xing’s last barrier of fear and redefined her life’s mission.

Now 49, the head nurse of Hainan Fifth People’s Hospital, also known as Hainan Skin Disease and Plastic Surgery Hospital, has spent three decades eradicating the stigma with radical compassion, earning her China’s highest medical honor, the Norman Bethune Award, on March 31.

“They weren’t afraid of us, but they were afraid for us,” Xing recalled. “That’s when I understood: dignity hurts worse than disease.”

When Xing graduated from a health vocational college in 1995 and began working at Hainan’s largest leprosy colony, isolation was the norm. Patients, many with untreated ulcers, lived behind walls and were abandoned by families. Medical staff wore hazmat-like gear.

Despite her family’s fears about the risks of her work, Xing changed that calculus with science. She adopted masking, gloving and sterilizing protocols so rigorous that direct contact became safe. Then she added what medicine couldn’t measure — sitting for hours listening to life stories and holding hands gnarled by nerve damage.

“Leprosy steals everything — jobs, marriages, even hugs,” said Xing, scrolling through photos of elderly patients on her phone. One image shows a man grinning as she fits him with custom shoes; another, a woman smiling while Xing dresses her wounds. “What they need most isn’t just treatment. It’s being seen.”

Her clinical breakthroughs are textbook cases: By combining regenerative wound tech with photon therapy, her team slashed chronic ulcer rates from 28 percent to 5 percent, significantly lowering amputation risks. The innovation now guides leprosy hospitals nationwide.

Beyond the clinic, Xing ventured into remote regions to conduct hands-on training. In 2019, she led a province-wide survey across 13 leprosy-affected villages, finding ulcer incidence rates as high as 18.9 percent. In response, she launched a mobile treatment campaign and trained 464 local caregivers, building a grassroots network of leprosy care specialists.

Yet her most fragile patients never leave the geriatric ward. Xing helped establish a tailored geriatric care system that treats both physical disabilities and social stigma.

“Some patients hadn’t held anyone’s hand in decades,” she said. “We’ve held over 100 hands in their last moments. No one should die remembering only pain.”

In 2023, Xing was awarded the Florence Nightingale Medal by the International Red Cross. She has since shared her experience with nearly 4,000 people through lectures, inspiring a new generation of health workers.

Xing has taken care of over 300 leprosy patients. “The elderly patients often call me ‘daughter’, a sign of their trust and the reason I keep going,” said Xing.

With China’s leprosy rates plummeting, she believes key challenges remain in early detection, especially in remote areas, and in comprehensive rehabilitation addressing both physical and psychological needs.

As a Party member for 23 years, Xing views her awards as a recognition of teamwork, not individual achievement. “My oath to serve the people guides everything — ward rounds, emergencies, trips to remote villages,” she said. “These honors are not just for me but they belong to thousands of front-line medical workers and leprosy control staff.”

chenbowen@chinadaily.com.cn

WITH the monsoon season underway in Pakistan, the threat of another dengue outbreak hangs over us. The warning signs are here: Sindh logged its first dengue-related casualty with the death of a young male patient at the Sindh Infectious Diseases Hospital. In June, Karachi recorded 32 new dengue incidents, with single cases in Mirpurkhas and Sukkur. This year, Sindh reported 295 dengue cases; 260 of these were from Karachi. While the June count is significantly lower than in the past four years, the health authorities cannot afford to let their guard down. Besides, climate change has altered the pattern of vector-borne infections as well as engendered new temperature-resilient mosquito species. Without a sustained, comprehensive programme, timely precautions and mass awareness, annual surges will be difficult to block.

In 2017, KP set an example by seeking help from the Punjab government, which had fought a dengue epidemic in 2011 with a remarkable strategy involving collaboration between Pakistani, Indonesian and Sri Lankan medical experts. New regulations were enforced to thwart the seasonal health emergency. The time has come for Sindh to follow suit. The province must prioritise the public’s well-being and implement an upgraded version of the Punjab template, alongside carrying out extensive fumigation drives as well as providing skilled medics and medicines to ease symptoms and avoid critical cases of low platelet counts. The fact that Punjab has been dengue-clear through June shows that through early directives and heightened public and administrative alertness, it has managed to contain the disease, which is laudable. To ensure that the populace does not have to endure repeated bouts of agony, deterrence initiatives must at the very least keep pace with mosquito breeding. Access to hygienic living conditions and cost-free dengue tests is the antidote to the Aedes aegypti mosquito that thrives in fresh water.

Published in Dawn, July 2nd, 2025

WASHINGTON: Struggle with math? A gentle jolt to the brain might help.

A new study published on Tuesday in PLOS Biology suggests that mild electrical stimulation can boost arithmetic performance — and offers fresh insight into the brain mechanisms behind mathematical ability, along with a potential way to optimise learning.

The findings could eventually help narrow cognitive gaps and help build a more intellectually equitable society, the authors argue.

“Different people have different brains, and their brains control a lot in their life,” said Roi Cohen Kadosh, a neuroscientist at the University of Surrey who led the research.

“We think about the environment — if you go to the right school, if you have the right teacher — but it’s also our biology.” Cohen Kadosh and colleagues recruited 72 University of Oxford students, scanning their brains to measure connectivity between three key regions.

Participants then tackled math problems that required either calculating answers or recalling memorised solutions.

They found that stronger connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which governs executive function, and the posterior parietal cortex, involved in memory, predicted better calculation performance.

When the researchers applied a painless form of brain stimulation using electrode-fitted caps — a technique known as transcranial random noise stimulation — the low performers saw their scores jump by 25-29 percent.

The team believes the stimulation works by enhancing the excitability of neurons and interacting with GABA, a brain chemical that inhibits excessive activity.

In fact, the stimulation helped underperformers reach or even surpass the scores of peers with naturally stronger brain wiring. But those who already performed well saw no benefit.

Published in Dawn, July 2nd, 2025

WASHINGTON: Struggle with math? A gentle jolt to the brain might help.

A new study published on Tuesday in PLOS Biology suggests that mild electrical stimulation can boost arithmetic performance — and offers fresh insight into the brain mechanisms behind mathematical ability, along with a potential way to optimise learning.

The findings could eventually help narrow cognitive gaps and help build a more intellectually equitable society, the authors argue.

“Different people have different brains, and their brains control a lot in their life,” said Roi Cohen Kadosh, a neuroscientist at the University of Surrey who led the research.

“We think about the environment — if you go to the right school, if you have the right teacher — but it’s also our biology.” Cohen Kadosh and colleagues recruited 72 University of Oxford students, scanning their brains to measure connectivity between three key regions.

Participants then tackled math problems that required either calculating answers or recalling memorised solutions.

They found that stronger connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which governs executive function, and the posterior parietal cortex, involved in memory, predicted better calculation performance.

When the researchers applied a painless form of brain stimulation using electrode-fitted caps — a technique known as transcranial random noise stimulation — the low performers saw their scores jump by 25-29 percent.

The team believes the stimulation works by enhancing the excitability of neurons and interacting with GABA, a brain chemical that inhibits excessive activity.

In fact, the stimulation helped underperformers reach or even surpass the scores of peers with naturally stronger brain wiring. But those who already performed well saw no benefit.

Published in Dawn, July 2nd, 2025

By sequencing 4,000-year-old genomes, scientists reveal that leprosy was entrenched in South America millennia before Europeans arrived, reshaping our understanding of its origins and spread.

Study: 4,000-year-old Mycobacterium lepromatosis genomes from Chile reveal long establishment of Hansen’s disease in the Americas. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

In a recent study published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, researchers analyzed Mycobacterium lepromatosis genomes from 4,000-year-old human remains, revealing a long history of leprosy in the Americas.

Leprosy (also known as Hansen’s disease) is caused by Mycobacterium leprae and M. lepromatosis. M. lepromatosis has been regarded as the second causal pathogen for Hansen’s disease and is associated with more severe forms of the disease, including Lucio’s phenomenon and diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Untreated individuals can develop chronic peripheral neuropathy and physical impairment. Many infected subjects remain asymptomatic, impeding diagnostic and control measures.

Ancient M. leprae genome analyses support its infectious potential spanning millennia. Humans are the primary host of Hansen’s disease, but maintenance of the causal bacteria in animals raises concerns about their potential as zoonotic reservoirs. Nine-banded armadillos are known M. leprae sources, while red squirrels can harbor both M. lepromatosis and M. leprae. The recent detection of M. leprae in archeological rodent bone suggests cross-species infectivity in historical periods.

Understanding of the evolutionary history and distribution of M. lepromatosis is limited, as only a few cases of infection have been molecularly confirmed. Studies suggest its presence in Southeast Asia and the Americas. Analyses involving ancient and modern genomic data consistently support the origin of M. leprae outside the Americas. However, the detection of M. lepromatosis has not been reported in archeological contexts.

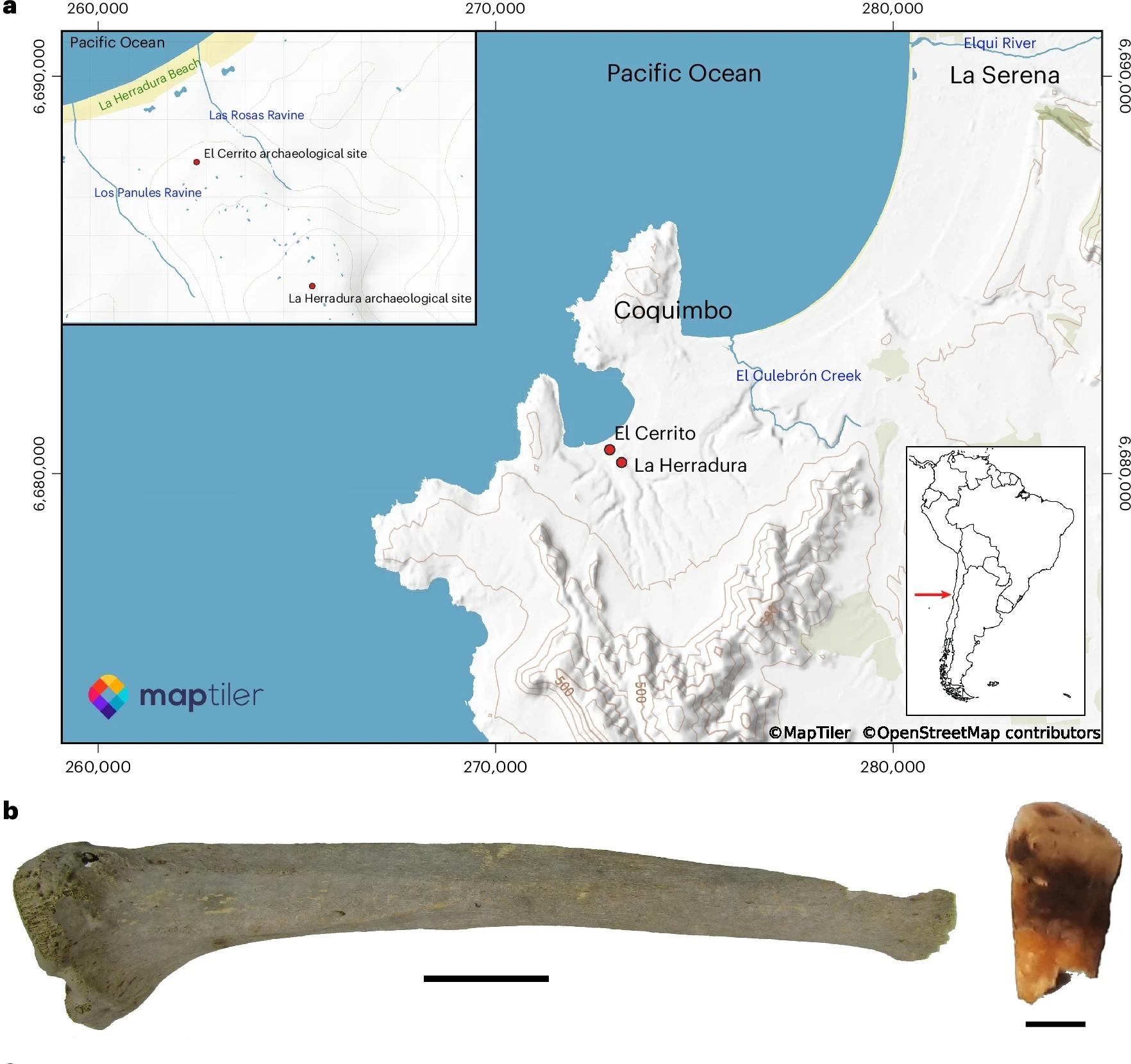

a, Map of the semi-arid region of Chile showing the location of the two archaeological sites under study. Coordinates follow the universal transverse mercator (UTM) system (Datum WGS 84, Zone 19J); values are given as easting and northing (m). Map created with the MapTiler plugin within QGIS. b, Skeletal elements that yielded the two ancient genomes of M. lepromatosis: left, tibia from ECR001 (scale bar, 5 cm); right, tooth from ECR003 (scale bar, 0.5 cm).

a, Map of the semi-arid region of Chile showing the location of the two archaeological sites under study. Coordinates follow the universal transverse mercator (UTM) system (Datum WGS 84, Zone 19J); values are given as easting and northing (m). Map created with the MapTiler plugin within QGIS. b, Skeletal elements that yielded the two ancient genomes of M. lepromatosis: left, tibia from ECR001 (scale bar, 5 cm); right, tooth from ECR003 (scale bar, 0.5 cm).

In the present study, researchers analyzed M. lepromatosis genomes from 4,000-year-old human skeletal remains from distinct archeological contexts. First, 19 bones and 35 teeth with pathological lesions suggestive of infection, belonging to 41 individuals, were sampled from five archaeological sites in Chile.

The paper notes that while the bone changes in the two infected individuals were consistent with Hansen’s disease, they were not definitively diagnostic on their own, underscoring the importance of molecular analysis for confirmation. A small quantity of each tissue was extracted, and a DNA library was constructed for sequencing.

Data were screened for various pathogenic viruses and bacteria following a hypothesis-free method. This revealed several thousand DNA fragments with homology to M. lepromatosis in two archeological tissues, a tooth from a male subject referred to as ECR003 at the El Cerrito site and a tibia from another male (ECR001) at the La Herradura site. Radiocarbon dating of these two elements indicated they were contemporaneous from 3,900 to 4,100 years ago.

DNA libraries were enriched using a probe set designed from a modern M. leprae reference panel, a methodological detail that resulted in some uneven coverage but still yielded exceptionally high-quality ancient genomes. These libraries were then sequenced to explore the suitability of genomic reconstruction. Various mycobacterial species were distinguished using a competitive mapping approach. The mean genomic coverage was 74-fold for ECR003 and 45-fold for ECR001 when mapped against a modern M. lepromatosis genome reference isolated from a Mexican patient.

Further, the researchers investigated divergence between M. leprae and M. lepromatosis given the genomic decay and reduction in M. leprae over evolutionary timescales. To this end, a pangenomic analysis revealed a high level of divergence, with about half of the protein-coding regions showing at least 50% sequence homology between the two pathogens. A mapping-based approach showed that the two pathogens shared only ~25% nucleotide identity.

Next, the relationship between M. lepromatosis and other mycobacterial pathogens was investigated by analyzing the 16S ribosomal RNA locus. This indicated that M. leprae is the closest relative, despite their extensive divergence.

Further, a conservative genome-level phylogenetic reconstruction was performed, focusing on the diversity within M. lepromatosis, and was limited to the two ancient genomes, four modern human genomes, and six modern red squirrel genomes.

There was a robust and distinct separation between rodent- and human-associated lineages, where the ancient genomes formed a sister clade to the cluster of all human M. lepromatosis sequences.

The study’s comparative analysis also called into question a previously reported M. lepromatosis genome from India, suggesting through competitive mapping that it showed far greater homology to M. leprae.

Furthermore, time-calibrated phylogenetic trees were generated using the radiocarbon ages of ECR001 and ECR003 skeletal elements, along with the collection year of all modern genomes, to estimate evolutionary rates and divergence times.

The evolutionary rate was estimated at 6.91 x 10-9 substitutions per site per year for M. lepromatosis, aligning with estimates for M. leprae. The median time for the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of M. lepromatosis was estimated to be approximately 26,800 years ago; however, the authors note that the small number of available genomes results in a wide potential date range of 4,206 to 115,340 years ago.

The divergence time for genomes from human hosts was estimated to be around 12,600 years (with a range of 5,304 to 49,659 years ago), while the tMRCA for the red squirrel clade was a much more recent 440 years.

Taken together, the study reveals a distinct evolutionary history for M. lepromatosis. This deep timeline, potentially stretching back to the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, contrasts sharply with other major pathogens, such as M. leprae and Yersinia pestis (the plague bacterium), which are thought to have emerged more recently in the Neolithic era with the rise of agriculture.

The fact that M. lepromatosis infections occurred in South America before the periods of known contact with European or Oceanian populations implies pathogen movement within human groups during an early peopling event or endemicity in the continent in a different reservoir species. The latter suggests that its current distribution originates from a post-colonial dissemination, making it one of the few diseases known to have emerged in the Americas.

The paper frames these findings within a ‘One Health’ perspective, calling for broader surveillance of animal reservoirs to better understand the disease’s ecology and zoonotic potential.

Journal reference:

KFF In the early days of the West Texas measles outbreak, Thang Nguyen eyed the rising number of cases and worried. His 4-year-old son was at risk because he had received only the first of the vaccine’s two doses.

So, in mid-March, he took his family to a primary care clinic at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

By the end of the visit, his son, Anh Hoang, had received one shot protecting against four illnesses — measles, mumps, rubella, and chickenpox. He also received a second shot against tetanus, diphtheria, and whooping cough, as well as a flu shot. His twin daughters, who had already had their measles vaccinations, got other immunizations.

Nguyen, who is a UTMB postdoctoral fellow in public health and infectious disease, said he asked clinic staff whether his family’s insurance would cover the checkups and immunizations. He said he was assured that it would.

Then the bills came.