- NM health department reports possible measles exposure in Albuquerque Source New Mexico

- Measles exposure reported at Albuquerque hotel KOB.com

- New Mexico Department of Health warns about possible measles exposure in Albuquerque KRQE

- Possible…

Category: 6. Health

-

NM health department reports possible measles exposure in Albuquerque – Source New Mexico

-

Hypervigilance, Anxiety Linked to Poor Treatment Outcomes in Esophageal Disorder

Livia Guadagnoli, ‘20 PhD, research assistant professor of Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, was lead author of the study published in Gastroenterology. Increased esophageal hypervigilance and anxiety were…

Continue Reading

-

Eating these 5 fruits in 2026 could transform your gut health

Fruits provide fiber and nutrients that support healthy digestion and gut balance. (iStock)

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

FIBER FOCUS: Experts say adding certain fiber-rich fruits to your diet can help strengthen your gut for…

Continue Reading

-

Commitment to Privacy – Virginia Commonwealth University

We collect limited information about web visitors and use cookies on our website to provide you with the most optimal experience. These cookies help us provide you with personalized content and improve our website. To learn more about our web…

Continue Reading

-

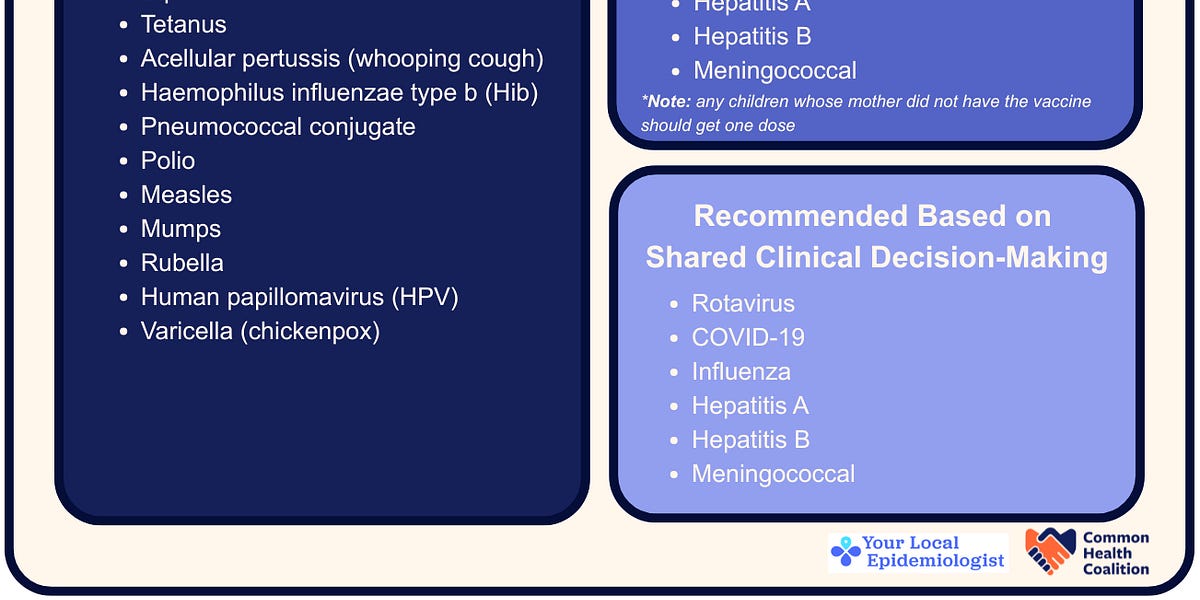

What it means for you

Well, he did it. He actually did it.

RFK Jr. unilaterally made sweeping changes to the routine vaccination schedule for children in the United States. This change isn’t based on new data or new evidence, but rather on political and ideological…

Continue Reading

-

APA Publishing Releases New Titles on Gaming Disorders, HIV Psychiatry, and the Lived Experience of

Washington, D.C. — American Psychiatric Association Publishing has released a new set of titles exploring key areas in psychiatric practice, including cultural perspectives in mental health, internet…

Continue Reading

-

Researchers achieve the first minimally invasive coronary artery bypass

Tuesday, January 6, 2026

For high-risk patients, the method could offer a safer alternative to open-heart surgery.

In a world first, a team of researchers at the National…

Continue Reading

-

The perfect way to switch off from work: the secret to a daily de-stress routine | Life and style

Marilyn Monroe once said: “A career is wonderful, but you can’t curl up with it on a cold night.” Only these days, you can. The march of technology, the rise of hybrid and remote working, and an increasing culture of presenteeism (working…

Continue Reading

-

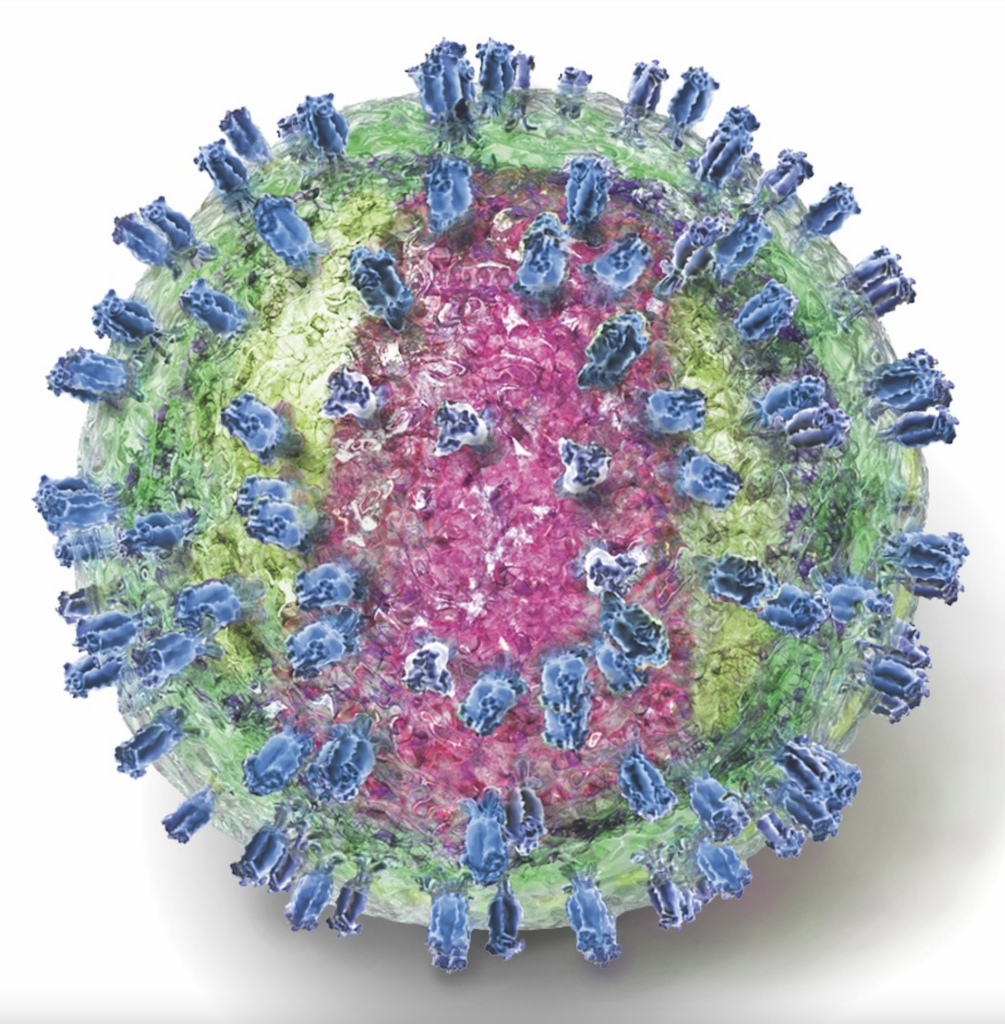

IAVI announces first vaccinations in IAVI G004, a Phase 1 clinical trial of a promising HIV vaccine approach

- In 2024, 40.8 million people were living with HIV, and 1.3 million people newly acquired HIV

- The IAVI/Scripps Research HIV vaccine development strategy aims to coach the immune system…

Continue Reading

-

Finding the right team for achondroplasia: Jeremy’s story

When his parents learned he would be born with achondroplasia, they began a journey for care that ended at our Skeletal Health Center. As an “older” mom, Erica Johnson was used to undergoing more…

Continue Reading